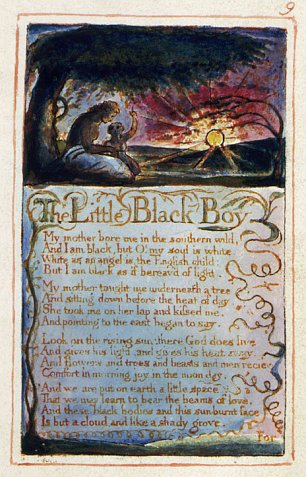

William Blake's "The Little Black Boy" (First Plate)

The Little Black Boy

by William Blake [1757-1827]

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child,

But I am black, as if bereav'd of light.

My mother taught me underneath a tree,

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east, began to say:

Look on the rising sun: there God does live,

And gives his light, and gives his heat away;

And flowers and trees and beasts and men receive

Comfort in morning, joy in the noonday.

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love;

And these black bodies and this sunburnt face

Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove.

For when our souls have learn'd the heat to bear,

The cloud will vanish; we shall hear his voice,

Saying: "Come out from the grove, my love & care,

And round my golden tent like lambs rejoice.''

Thus did my mother say, and kissed me;

And thus I say to little English boy:

When I from black and he from white cloud free,

And round the tent of God like lambs we joy,

I'll shade him from the heat, till he can bear

To lean in joy upon our father's knee;

And then I'll stand and stroke his silver hair,

And be like him, and he will then love me.

Blake also spoke clearly and forthrightly for equality between the races in his visual art. Blake depicted the horrors of racism and slavery more graphically than he did any other horrors ...

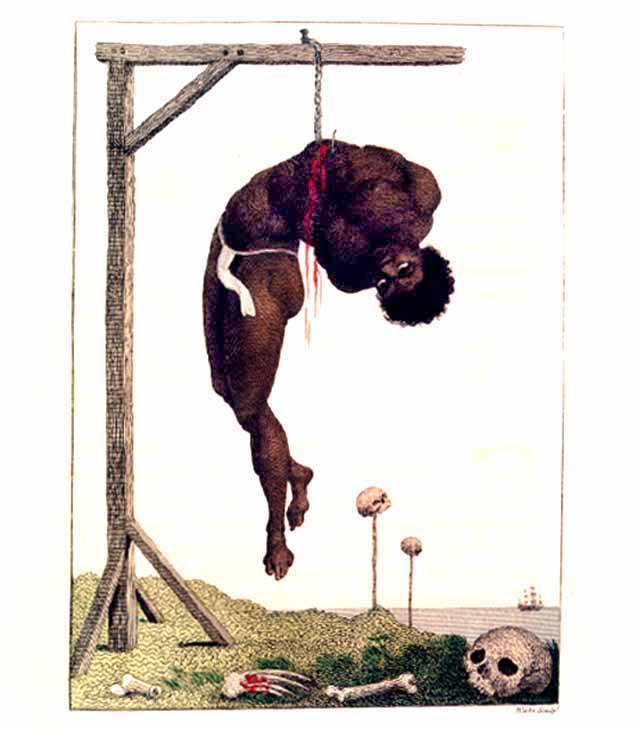

William Blake's "A Negro Hung Alive"

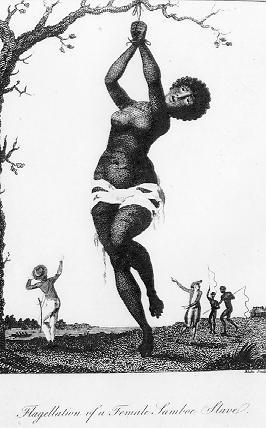

William Blake's "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave"

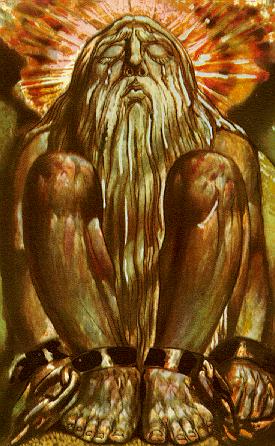

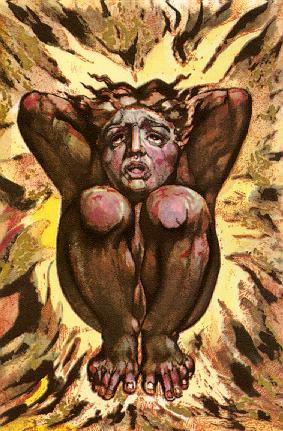

... but he seemed to go beyond that to "connect" the suffering of slaves with the lot of suffering mankind, even poets, symbolized in the second image below by Los ...

William Blake's "Urizen in Fetters, Tears streaming from His Eyes"

William Blake's "Los, Symbol of Poetic Genius, Consumed by Flames"

Blake and other early Romantic poets including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey, opposed slavery. In 1796 John Gabriel Stedman, a mercenary, published his memoirs of a five-year expedition against ex-slaves in Surinam; his book included a number of engraved illustrations by Blake depicting the horrifically cruel treatment of recaptured slaves. The first of these engravings has been "construed as an explicit attack on the slave trade" because Blake depicted "the skulls of the murdered slaves looking out over the sea to a slave ship in the distance while the most recent victim of plantation cruelty swings on the gallows in the foreground." These images were unique at that time for their graphic depiction of human suffering. Stedman's book and Blake's illustrations became part of abolitionist literature.

According to the "William Blake Biography" the poet was a "prophet against empire" who opposed slavery "over the course of his lifetime." Through his poetry and art "he was able both to counter pro-slavery propaganda and to complicate typical abolitionist verse and sentiment with a profound and unique exploration of the effects of enslavement and the varied processes of empire." The biography concludes: "Blake was among the few British writers who actively advocated slave rebellion and believed that it was at the edges of empire that true revolutions would occur."

The Gettysburg Address

Abraham Lincoln [1809-1865]

Four score and seven years ago

our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation,

conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition

that all men are created equal.

Make no mistake about it: Abraham Lincoln was a true poet, which you can easily confirm by clicking here: Abraham Lincoln, Poet. Lincoln's greatest poem, the Gettysburg Address, contains his two great themes: that the Union must be preserved, and that the fundamental proposition of that Union was that all men were created equal and thus were self-evidently entitled to Liberty (which he capitalized). That slavery was abolished and yet the Union remains is a lasting testament to an extraordinary man who happened to be a wonderful writer as well.

Leaves of Grass

Walt Whitman [1819-1862]

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Harold Bloom once opined that Shakespeare "invented" the modern human consciousness. If so, Walt Whitman may have created the modern American consciousness, or at persuaded it to become more open-minded and tolerant. Whitman seemed to believe that autoeroticism, homosexuality and other things considered "evil" by church and state were, in fact, merely part of normal human life. He invited his readers to be tolerant freethinkers and to love freely. He was the second major poet of the "make love, not war" school, after Blake. Because Whitman was the first major free verse poet, he was highly influential with American and English poets to come, and with poets all around the world who chose to break the rules of formal poetry, or at least greatly relax them. No other English poet with the possible exception of Shakespeare has had more influence on poets and poetry around the world. The fact that Whitman was so generous in spirit and gregarious in nature, and became so influential, has no doubt helped many other poets, songwriters, musicians and artists become more freethinking and tolerant themselves. In effect, he helped change the culture of modern art.

Dover Beach

by Matthew Arnold [1822-1888]

The sea is calm to-night,

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The sea of faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

"Dover Beach" may be the first modern English poem. When Arnold speaks of the "Sea of Faith" retreating, he seems to be setting the stage for Modernism, which to some degree was the reaction of men who began to increasingly suspect that the "wisdom" contained in the Bible was far from the revelation of an all-knowing God.

"All right, then, I'll go to hell!" from Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain [1835-1910]

So I was full of trouble,

full as I could be;

and didn't know what to do.

At last I had an idea; and I says,

I'll go and write the letter—and then see if I can pray.

Why, it was astonishing,

the way I felt as light as a feather right straight off,

and my troubles all gone.

So I got a piece of paper and a pencil,

all glad and excited,

and set down and wrote:

Miss Watson, your runaway nigger Jim is down here two mile below Pikesville,

and Mr. Phelps has got him and he will give him up for the reward if you send.

—Huck Finn

I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life,

and I knowed I could pray now.

But I didn't do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking—

thinking how good it was all this happened so,

and how near I come to being lost and going to hell.

And went on thinking.

And got to thinking over our trip down the river;

and I see Jim before me all the time:

in the day and in the night-time,

sometimes moonlight,

sometimes storms,

and we a-floating along,

talking and singing and laughing.

But somehow I couldn't seem to strike no places to harden me against him,

but only the other kind.

I'd see him standing my watch on top of his'n,

'stead of calling me,

so I could go on sleeping;

and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog;

and when I come to him again in the swamp,

up there where the feud was; and suchlike times;

and would always call me honey,

and pet me,

and do everything he could think of for me,

and how good he always was;

and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had smallpox aboard,

and he was so grateful,

and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world,

and the only one he's got now;

and then I happened to look around and see that paper.

It was a close place.

I took it up, and held it in my hand.

I was a-trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it.

I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

"All right, then, I'll go to hell!"—and tore it up.

While Mark Twain wrote a few poems here and there, he is best-known for his prose, and rightfully so. I have recast my favorite passage from Huckleberry Finn as free verse poetry, and I believe it passes muster. This is an important passage in American literature because the most famous American writer makes the point that if our religion teaches us to discriminate against our fellowmen, something is fundamentally wrong with our beliefs. Huckleberry Finn is one of the most-read books by an American writer, and hopefully has helped convince many people to follow the example of Huckleberry Finn, by choosing friendship, compassion and tolerance over the highly dubious "morality" preached by narrow-minded religious types.

I - Easter Hymn

by A. E. Housman [1859-1936]

If in that Syrian garden, ages slain,

You sleep, and know not you are dead in vain,

Nor even in dreams behold how dark and bright

Ascends in smoke and fire by day and night

The hate you died to quench and could but fan,

Sleep well and see no morning, son of man.

But if, the grave rent and the stone rolled by,

At the right hand of majesty on high

You sit, and sitting so remember yet

Your tears, your agony and bloody sweat,

Your cross and passion and the life you gave,

Bow hither out of heaven and see and save.

A. E. Housman was a non-believing homosexual ruled over by Christian philistines who would have crucified him twice: once for his "lack of faith" and again for his sexuality. And yet Housman seems like the better Christian, because rather than asking to be saved personally at the expense of billions of other human souls, he asked Jesus Christ to save everyone, if he was able. Housman's poem is a protest against a religion that all too often preaches love while practicing hatred, intolerance, hypocrisy and war.

XII

by A. E. Housman [1859-1936]

The laws of God, the laws of man,

He may keep that will and can;

Not I: let God and man decree

Laws for themselves and not for me;

And if my ways are not as theirs

Let them mind their own affairs.

Their deeds I judge and much condemn,

Yet when did I make laws for them?

Please yourselves, say I, and they

Need only look the other way.

But no, they will not; they must still

Wrest their neighbour to their will,

And make me dance as they desire

With jail and gallows and hell-fire.

And how am I to face the odds

Of man's bedevilment and God's?

I, a stranger and afraid

In a world I never made.

They will be master, right or wrong;

Though both are foolish, both are strong.

And since, my soul, we cannot fly

To Saturn nor to Mercury,

Keep we must, if keep we can,

These foreign laws of God and man.

Housman strongly protested the idea that Christians should be allowed to use the Bible to create arbitrary, unnecessary laws for nonbelievers like himself. He may have been thinking of Oscar Wilde, who was jailed on charges of homosexuality and died shortly after his release. Why should Housman have believed in the the highly dubious "morality" of a religion that damned him to "jail and gallows and hell-fire" just because he preferred men to women, sexually? This may be the first great protest poems written by a gay poet against his Christian oppressors.

Excerpts from "More Poems," XXXVI

by A. E. Housman [1859-1936]

Here dead lie we because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

I have loved the four lines by Housman above, since I first read them. He could write movingly without indulging in images, melodrama or sophistry, and rivals Shakespeare in what he could accomplish with direct statement. Housman is certainly a major poet, and one of our very best critics of human societies and religion, along with Blake, Twain and Wilde. A good number of his poems can be found on the Masters page of The HyperTexts.

An Irish Airman Foresees His Death

by William Butler Yeats [1865-1939]

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan's poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

W. B. Yeats was probably the last of the great Romantics, and the first of the great Modernists. He wrote a good number of truly great poems, and remains an essential poet of the highest rank. "An Irish Airman Foresees His Death" is a wonderful poem that illustrates how the people who die in war often have little to gain and everything to lose. Yeats also wrote eloquently about how the Irish people felt living under the thumb of imperial England. Several of Yeats' poems can be found on the Masters page of The HyperTexts.

Directive

by Robert Frost [1874-1963]

Back out of all this now too much for us,

Back in a time made simple by the loss

Of detail, burned, dissolved, and broken off

Like graveyard marble sculpture in the weather,

There is a house that is no more a house

Upon a farm that is no more a farm

And in a town that is no more a town.

The road there, if you'll let a guide direct you

Who only has at heart your getting lost,

May seem as if it should have been a quarry –

Great monolithic knees the former town

Long since gave up pretense of keeping covered.

And there's a story in a book about it:

Besides the wear of iron wagon wheels

The ledges show lines ruled southeast-northwest,

The chisel work of an enormous Glacier

That braced his feet against the Arctic Pole.

You must not mind a certain coolness from him

Still said to haunt this side of Panther Mountain.

Nor need you mind the serial ordeal

Of being watched from forty cellar holes

As if by eye pairs out of forty firkins.

As for the woods' excitement over you

That sends light rustle rushes to their leaves,

Charge that to upstart inexperience.

Where were they all not twenty years ago?

They think too much of having shaded out

A few old pecker-fretted apple trees.

Make yourself up a cheering song of how

Someone's road home from work this once was,

Who may be just ahead of you on foot

Or creaking with a buggy load of grain.

The height of the adventure is the height

Of country where two village cultures faded

Into each other. Both of them are lost.

And if you're lost enough to find yourself

By now, pull in your ladder road behind you

And put a sign up CLOSED to all but me.

Then make yourself at home. The only field

Now left's no bigger than a harness gall.

First there's the children's house of make-believe,

Some shattered dishes underneath a pine,

The playthings in the playhouse of the children.

Weep for what little things could make them glad.

Then for the house that is no more a house,

But only a belilaced cellar hole,

Now slowly closing like a dent in dough.

This was no playhouse but a house in earnest.

Your destination and your destiny's

A brook that was the water of the house,

Cold as a spring as yet so near its source,

Too lofty and original to rage.

(We know the valley streams that when aroused

Will leave their tatters hung on barb and thorn.)

I have kept hidden in the instep arch

Of an old cedar at the waterside

A broken drinking goblet like the Grail

Under a spell so the wrong ones can't find it,

So can't get saved, as Saint Mark says they mustn't.

(I stole the goblet from the children's playhouse.)

Here are your waters and your watering place.

Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.

Robert Frost in "Directive" was writing about the dark load orthodox Christianity heaps on the slender shoulders of innocent children, when it tells them that the Bible is the "infallible" and/or "inerrant" word of God, and that human beings live in danger of eternal torment. Frost understood all too well the emotional, psychological and spiritual damage children can suffer, when they read verses in the Bible that say most human beings are "predestined" for eternal damnation before they are born, and that Jesus Christ deliberately misled most of his followers so that they could not be saved, keeping his true teachings only for his inner circle [Mark 4:10-12]. Frost's magnificent poem is a protest against his Christian upbringing and its "guide" who "only has at heart your getting lost," whose followers put up signs marked "CLOSED to all but me."

The Unreturning

by Wilfred Owen [1893-1918]

Suddenly night crushed out the day and hurled

Her remnants over cloud-peaks, thunder-walled.

Then fell a stillness such as harks appalled

When far-gone dead return upon the world.

There watched I for the Dead; but no ghost woke.

Each one whom Life exiled I named and called.

But they were all too far, or dumbed, or thralled,

And never one fared back to me or spoke.

Then peered the indefinite unshapen dawn

With vacant gloaming, sad as half-lit minds,

The weak-limned hour when sick men's sighs are drained.

And while I wondered on their being withdrawn,

Gagged by the smothering Wing which none unbinds,

I dreaded even a heaven with doors so chained.

Dulce Et Decorum Est

by Wilfred Owen [1893-1918]

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime...

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

"Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" is from Horace's Odes and means: "It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country." This is one of the first and best graphic anti-war poems in the English language. Wilfred Owen had a mental breakdown during World War I, was treated, recovered, and returned to the front, only to be killed shortly before the Armistice. Wilfred Owen is a war poet without peer, and one of the first great modern poets. His poem "Dulce et Decorum Est" is probably the best anti-war poem in the English language, perhaps in any language. If man ever grows wise enough as a species to abolish war, Wilfred Owen's voice, echoed in thousands of other poems and songs, will have been a major catalyst.

i sing of Olaf glad and big

by e. e. cummings [1894-1962]

i sing of Olaf glad and big

whose warmest heart recoiled at war:

a conscientious object-or

his wellbelovéd colonel(trig

westpointer most succinctly bred)

took erring Olaf soon in hand;

but—though an host of overjoyed

noncoms(first knocking on the head

him)do through icy waters roll

that helplessness which others stroke

with brushes recently employed

anent this muddy toiletbowl,

while kindred intellects evoke

allegiance per blunt instruments—

Olaf(being to all intents

a corpse and wanting any rag

upon what God unto him gave)

responds,without getting annoyed

"I will not kiss your fucking flag"

straightway the silver bird looked grave

(departing hurriedly to shave)

but—though all kinds of officers

(a yearning nation's blueeyed pride)

their passive prey did kick and curse

until for wear their clarion

voices and boots were much the worse,

and egged the firstclassprivates on

his rectum wickedly to tease

by means of skilfully applied

bayonets roasted hot with heat—

Olaf(upon what were once knees)

does almost ceaselessly repeat

"there is some shit I will not eat"

our president,being of which

assertions duly notified

threw the yellowsonofabitch

into a dungeon,where he died

Christ(of His mercy infinite)

i pray to see;and Olaf,too

preponderatingly because

unless statistics lie he was

more brave than me:more blond than you.

The poem "i sing of Olaf glad and big" denounces the brutal excesses of what William Blake called the "Satanic Mills" and Dwight D. Eisenhower called the "military-industrial complex." It makes a compelling case for the warmongers to be punished, rather than the conscientious objectors.

Minstrel Man

by Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

And my throat

Is deep with song,

You did not think

I suffer after

I've held my pain

So long.

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

You do not hear

My inner cry:

Because my feet

Are gay with dancing,

You do not know

I die.

Langston Hughes was one of the most important protest poets of all time. His poetry contained elements of traditional poetry, negro spirituals and the blues.

Naming of Parts

by Henry Reed [1914-1986]

"Vixi duellis nuper idoneus

Et militavi non sine glori"

Today we have naming of parts. Yesterday,

We had daily cleaning. And tomorrow morning,

We shall have what to do after firing. But today,

Today we have naming of parts. Japonica

Glistens like coral in all of the neighboring gardens,

And today we have naming of parts.

This is the lower sling swivel. And this

Is the upper sling swivel, whose use you will see

When you are given your slings. And this is the piling swivel,

Which in your case you have not got. The branches

Hold in the gardens their silent, eloquent gestures,

Which in our case we have not got.

This is the safety-catch, which is always released

With an easy flick of the thumb. And please do not let me

See anyone using his finger. You can do it quite easily

If you have any strength in your thumb. The blossoms

Are fragile and motionless, never letting anyone see

Any of them using their finger.

And this you can see is the bolt. The purpose of this

Is to open the breech, as you see. We can slide it

Rapidly backwards and forwards: we call this

Easing the spring. And rapidly backwards and forwards

The early bees are assaulting and fumbling the flowers:

They call it easing the Spring.

They call it easing the Spring: it is perfectly easy

If you have any strength in your thumb: like the bolt,

And the breech, and the cocking-piece, and the point of balance,

Which in our case we have not got; and the almond-blossom

Silent in all of the gardens and the bees going backwards and forwards,

For today we have naming of parts.

Henry Reed is likely to be remembered by this one poem, but fortunately for him (and for us) it should make him immortal. His poem considers the irony of young men learning the mechanisms of war during the season of love and renewal, Spring. When I read his lovely poem, I immediately think of Pete Seeger's "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?"

Postcard 1

by Miklós Radnóti

written August 30, 1944

translated by Michael R. Burch

Out of Bulgaria, the great wild roar of the artillery thunders,

resounds on the mountain ridges, rebounds, then ebbs into silence

while here men, beasts, wagons and imagination all steadily increase;

the road whinnies and bucks, neighing; the maned sky gallops;

and you are eternally with me, love, constant amid all the chaos,

glowing within my conscience — incandescent, intense.

Somewhere within me, dear, you abide forever —

still, motionless, mute, like an angel stunned to silence by death

or a beetle hiding in the heart of a rotting tree.

Postcard 2

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 6, 1944 near Crvenka, Serbia

translated by Michael R. Burch

A few miles away they're incinerating

the haystacks and the houses,

while squatting here on the fringe of this pleasant meadow,

the shell-shocked peasants quietly smoke their pipes.

Now, here, stepping into this still pond, the little shepherd girl

sets the silver water a-ripple

while, leaning over to drink, her flocculent sheep

seem to swim like drifting clouds ...

Postcard 3

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 24, 1944 near Mohács, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

The oxen dribble bloody spittle;

the men pass blood in their piss.

Our stinking regiment halts, a horde of perspiring savages,

adding our aroma to death's repulsive stench.

Postcard 4

by Miklós Radnóti

his final poem, written October 31, 1944 near Szentkirályszabadja, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

I toppled beside him — his body already taut,

tight as a string just before it snaps,

shot in the back of the head.

"This is how you’ll end too; just lie quietly here,"

I whispered to myself, patience blossoming from dread.

"Der springt noch auf," the voice above me jeered;

I could only dimly hear

through the congealing blood slowly sealing my ear.

In my opinion, Miklós Radnóti is the greatest of the Holocaust poets, and one of the very best anti-war poets, along with Wilfred Owen and singer-songwriters like Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and John Lennon.

I Have a Dream

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. [1929-1968]

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia

the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners

will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

... I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation

where they will not be judged by the color of their skin

but by the content of their character ....

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted,

every hill and mountain shall be made low,

the rough places will be made plain,

and the crooked places will be made straight,

and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,

and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., like Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, resorted to poetry when everything was on the line. It's ironic that today people on the far left, such as Al Sharpton, and people on the far right, like Glen Beck, all want to be aligned with Dr. King and his message of equality. I consider that to be a very hopeful sign that things are improving, and will continue to improve. Progress, after all, begins with what we consider the goal to be.

Distant light

by Walid Khazindar [1950-]

Harsh and cold

autumn holds to it our naked trees:

If only you would free, at least, the sparrows

from the tips of your fingers

and release a smile, a small smile

from the imprisoned cry I see.

Sing! Can we sing

as if we were light, hand in hand

sheltered in shade, under a strong sun?

Will you remain, this way

stoking the fire, more beautiful than necessary, and quiet?

Darkness intensifies

and the distant light is our only consolation —

that one, which from the beginning

has, little by little, been flickering

and is now about to go out.

Come to me. Closer and closer.

I don't want to know my hand from yours.

And let's beware of sleep, lest the snow smother us.

Translated by Khaled Mattawa from the author's collections Ghuruf Ta'isha (Dar al-Fikr, Beirut, 1992) and Satwat al-Masa (Dar Bissan, Beirut, 1996). Reprinted from Banipal No 6. Translation copyright Banipal and translator. All rights reserved. Walid Khazindar was born in 1950 in Gaza City. While this wonderful poem may not be a war poem, per se, the Palestinians of Gaza have lived under an Israeli military siege and naval blockade for many years, so I think it qualifies.

Word Made Flesh

by Ann Drysdale [birth date unknown, still living and writing]

On the broad steps of the Basilica

The feckless hopefully hold out their hands,

Often with some success; the privileged

Lighten their consciences by a few pence

On their way to receive the sacrament.

On the seventeenth step two beggars sit

Paying no regard to the worshippers

Who file past on their way to salvation.

They do not ask for alms. They are engrossed,

Skillfully masturbating one another.

Most who have noticed this pretend they haven’t;

Some of the other beggars wish they wouldn’t.

Poor relief is incumbent on the rich

And by taking things into their own hands

They spoil the scene for everybody else.

Our Lord said, “silver and gold have I none

But such as I have give I thee”. The words

Are here made flesh; with beatific sigh

One gives the other benison, slipping

All that he has into the waiting hand

Of somebody who shares his human need.

The newly shriven filter down the steps

Averting their eyes from the seventeenth,

Where the first beggar, in a state of grace,

Works selflessly towards the second coming.

This fine poem by Ann Drysdale begs the question: "What would Jesus say, and do?"

So there you have them: the best protest poems of all time, according to me. I'm sure every reader's choices will be different, but if you added a poem or three to yours, having read mine, hopefully you will consider your time here well spent.

The HyperTexts