The HyperTexts

Bloodshed in the Sahara: the Sins of Colonialism

and the Plight of the Sahrawi

(including Sahrawi Genocide Poetry)

compiled and edited

by Michael R. Burch,

an editor

and publisher of Holocaust and

Nakba poetry

Epitaph for a Sahrawi Child (I)

by Michael R. Burch

I was only a child

in the Saharan wild.

What matter — my death

as long as you draw breath?

Forget me — I die.

Never ask yourselves, Why?

Epitaph for a Sahrawi Child (II)

by Michael R. Burch

I lived as best I could, and then I died.

Be careful where you step: the grave is wide.

Should it matter to the world that yet another indigenous people is being

trodden underfoot by colonialists? This time the people being denied equal human

rights and self-determination are the Sahrawis, the descendents of Western Sahara

nomads. The Arabic word Sahrāwī literally means "of the Sahara." There

are various transliterations of the word:

English: Saharaui, Saharaoui, Sahrawi or Saharawi

French: Sahraoui, Saharaui

Italian: Saharawi,Saharaui

Portuguese: Saaráuis, Sarianos, Saarianos

Spanish: Saharaui (saharauita)

In order to understand the situation of the nameless

Sahrawi child of my poems, we need to understand what is happening to them today,

and the root causes of the catastrophe. Pertinent questions include:

Why are Morocco and France blocking attempts to have the UN monitor human rights abuses of

innocent Sahrawis and peace activists?

Doesn't this imply that there is something to be hidden: i.e., human rights

abuses?

Why did Morocco expel all foreign journalists before conducting what has been

called a massacre?

Is it because they didn't want the world to see what they planned to do?

Why is the Spanish judge Baltasar

Garzon conducting hearings about genocide, murder and torture committed by

Morocco since 1975?

Why is the United States once again silent when one of its "allies" practices

systematic racial injustices?

Why did Morocco imprison and allegedly torture Aminatou Ali

Ahmed Haidar, the Sahrawi Gandhi?

Should the U.S. have "allies" who imprison and torture women for demanding human

rights for their people?

Why did the King of Morocco build a 2,700 km separation barrier

on the advice of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon?

Why are there so many strong, disturbing parallels between what is happening to the

Palestinians and the Sahrawi?

Are we once again seeing what happens when colonial empires trample the human

rights of indigenous peoples?

Why has the U.S. media not reported these events? Is there a cover-up, or only

unconscionable apathy?

"Genocide" and "massacre" are strong words, which have been used recently in

relation to events that took place in Laayoune over a period of several days in

November, 2010.

First, let's consider different press releases to determine whether or not a massacre

took place. Here is an article that appeared in the New York Times on

December 9, 2010, on page A6 of the New York edition:

Desert Land in Limbo Is Torn Apart

by Bryan Denton

LAAYOUNE, Western Sahara — Dozens of buildings are still blackened from fire on

this remote desert city’s main boulevard, their windows shattered, their doors

boarded up. A hostile silence has reigned since the riot that broke out here

last month, leaving 11 Moroccan officers dead and hundreds of people injured.

Laayoune is a modern city of 300,000 with its own

airport. The violence — the worst seen here in decades — has renewed a

long-festering conflict between Morocco, which governs Western Sahara, and the

separatist Polisario Front, based in and supported by neighboring Algeria.

Many fear the episode will sow more chaos in this

Colorado-size territory on the Atlantic coast, or even create an opening for Al

Qaeda, which has gained a foothold in neighboring countries in northwest Africa

in recent years.

“There are real social tensions in Laayoune, but they

are being fueled by the cold war between Morocco and Algeria,” said Tlaty Tarik,

a political analyst. “This situation is becoming more dangerous, because of the

violence and because Al Qaeda is now present in the region.”

The riot began after the police evacuated a protest camp

set up just outside this city by Sahrawis, the once nomadic native people of the

area, who are now outnumbered by wealthier Moroccan emigrants from the north.

Knife-wielding thugs — who may have had a political agenda — appear to have

hijacked the peaceful protest. The security forces later retaliated, detaining

and beating dozens of Sahrawis, according to witnesses and a report by Human

Rights Watch.

Ever since, divisions appear to have deepened, both

among the Sahrawis themselves, and with Moroccans living in this newly built

city of tidy houses.

“After what happened, nothing feels normal, and people

don’t feel safe here,” said a 25-year-old Sahrawi man named Laghdaf, who was

sitting on the steps of a half-built cinder-block house recently. Some Sahrawis

blame members of their own community, he said. Others say the Moroccan state has

treated them unjustly.

The unrest has spread beyond Western Sahara. On Sunday,

hundreds of thousands of Moroccans rallied in Casablanca, denouncing Spanish

political parties and newspapers that had accused Morocco of carrying out a

massacre in Laayoune.

A fog of rumors and propaganda has helped obscure the

facts about what happened here last month. The Polisario Front still maintains

that the Moroccan authorities carried out a massacre after evacuating the camp,

where about 12,000 people had gathered to protest social and economic

conditions. “More than 30 people were killed,” some of them buried alive, Ahmed

Boukhari, the Polisario representative at the United Nations, said in a

telephone interview. Similar stories have appeared in the Algerian press.

The truth, it soon emerged, was virtually the opposite:

knife-wielding gangs from the camp attacked unarmed Moroccan security officers,

killing 11 of them, according to the police, witnesses and human rights

advocates. Gruesome video footage captured during the attacks shows one masked

man deftly cutting the throat of a prone Moroccan officer, and another urinating

on the body of a dead fireman.

The savage and premeditated style of the killings

prompted speculation that Qaeda-style militants might have been involved, but

there is no evidence of that. Two or three civilians died, by most accounts, in

what appeared to have been accidents. All told, 238 officers were injured, said

Mohamed Dkhissi, the city’s police prefect.

“We had to choose: a muscular intervention that risked

mass casualties, or not to use force,” said Mohamed Jelmous, the governor of the

Laayoune district.

But the arrests and beatings that took place afterward

could spread more anger among young Sahrawis, rights groups say.

Moroccan officials concede that the tensions here are

rooted partly in their own mistakes. They have doled out land and money to new

Sahrawi refugees from Polisario-controlled areas, a policy aimed at winning

hearts and minds that has angered the original Sahrawi residents. “There has

been corruption and poor administration, and this has fed the anger,” said

Mohamed Taleb, the director of a government-aligned human rights group here.

The problem is also partly a colonial legacy. Morocco

first occupied Western Sahara in 1975, after the Spanish, who had ruled it as a

colony for almost a century, withdrew. The Polisario, formed with Algerian

support, demanded independence for the region. It began waging a guerrilla war

and lobbied other countries to recognize a Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic with

Laayoune as its capital. It had some success (mostly among African nations),

though the number of supporters waxed and waned according to political

expediency.

The United Nations helped broker a cease-fire in 1991,

with the agreement that a referendum would be held to decide whether Western

Sahara would be independent or remain part of Morocco. That has not happened,

because Morocco and the Polisario cannot agree on who should be allowed to take

part.

In the meantime, Morocco has poured money into Laayoune,

making the debate over independence almost an anachronism. What was once a

Spanish fort and a cluster of tents is now a modern city of 300,000, a

profitable hub for fishing and phosphate mining with its own airport. Sahrawis

now constitute less than 40 percent of the population. Independence would in all

likelihood turn Laayoune into an Algerian satellite. Moroccans in the north, who

are keenly aware of the money their government has spent here, say that prospect

is intolerable.

In 2007, Morocco proposed that Western Sahara be granted

autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty, an idea that found favor with the United

States and France. Many Sahrawis seem to like the idea. Earlier this year, the

former security chief of the Polisario, Mustapha Salma, who went to Laayoune

under a program of exchange visits, publicly declared his support for the

autonomy proposal. But the Polisario has held firm to its demands for

independence. When Mr. Salma returned to the Polisario’s base in Algeria, he was

arrested. He then disappeared, and is now reported to be in Mauritania.

Diplomacy aside, some Sahrawis say they have never been

truly accepted by the Moroccan authorities, and feel that they are living under

an occupation, even if they believe independence is not a viable option.

Joblessness among young Sahrawis, many say, is a cause of the violence.

“All Sahrawis live in fear,” said Ghania Djeini, the

director of a human rights group. “There is now a hatred between Moroccans and

Sahrawis, and the attacks on security forces show this hatred.”

Ms. Djeini reeled off grievances like job

discrimination, government corruption and “disappearances” that took place in

the 1980s and 90s. These disappearances happened throughout Morocco during those

years, not just in the Sahrawi area.

Since the events of Nov. 8, many Moroccans here have

fresh grievances of their own. The bad blood does not bode well for Western

Sahara’s future.

“What Algeria did is not right,” said Abderrahim

Bougatya, the father of the officer whose throat was cut last month, as he sat

next to his wife in the family living room, tears running down his cheeks. “They

have burned our hearts. They have hurt us a lot.”

[While the New York Times article makes it seem the Moroccan police did

not set out with the intention of committing genocide or massacring innocent

civilians, there are troubling questions. For instance,

why were journalists expelled from the region? Why are people on the ground

claiming that the Moroccan forces ended up using what sounds like Gestapo tactics? Doesn't

the one normally precede the other, because if a state is planning to use Gestapo

tactics, it certainly doesn't want anyone filming and recording the evidence.

Let's take a look at what other people have reported. The next report comes from

an aid worker; her report makes it sound as though, even if the initial violence

was instigated by aggressors who infiltrated a peaceful demonstration, the Moroccan government

may have planned to use extreme measures because it evicted foreign journalists

before using devastating force. So even if the initial plan was to use peaceful

methods if they worked, it seems quite possible that "Plan B" was to crush any

opposition.]

Urgent—Saharawi Massacre in Western Sahara

Published November 16, 2010

Spain, Morocco, a displaced people and the UN are mixing it up tragically in an

unfolding travesty that’s receiving scarce media attention due to journalist

expulsions* ... this just crossed my desk from an aid worker who’s on the ground.

Please read ... pray ... forward this on ... and consider how we might take action:

*Update: This human rights abuse does seem to be getting

at least some media attention.

Hello ... I am in the camps right now, where we have a

large team on the ground. We are in the midst of a never-before experience here.

Please read the following message and consider passing it on to anyone who might

be able to help ... either through prayer or in a practical way.

Thank you! Janet

URGENT ... URGENT ... URGENT ... URGENT ... URGENT ... Nov. 10, 2010

This is an urgent plea on behalf of the Saharawi people.

At this moment in time, the situation has become explosive. We, American

citizens, are in the Saharawi refugee camps, watching a nightmare unfold before

our very eyes. Tens of thousands of Saharawi

were amassing in a peaceful demonstration “camp” outside their former capital

city of Layoune, Western Sahara. Morocco, the occupying government since 1975,

expelled all journalists and news media last week, cutting the homeland off from

any outside witnesses.

Monday, Nov. 8, 2010 ... Moroccan forces surrounded the

peaceful, unarmed protest “camp” and began a crackdown; in the early morning

hours they began burning tents, beating women and children, spraying the

Saharawi with tear gas and hot water, and then turned to the use of live

ammunition. [Note: I have seen videos which make it appear that some of the

protestors were armed with knives, and used gasoline to create incendiary

devices, so it seems possible that the police started off using nonviolent or

less violent tactics, encountered resistance, then resorted to more violent

tactics themselves. The New York Times article above seems to roughly

confirm what I saw in footage shot from a helicopter with a clear view of the

event. However, if Morocco has been practicing systematic racial injustices and

jailing and torturing human rights and peace activists, it should expect to

encounter resistance and shouldn't "bring down the hammer" on oppressed people

collectively.]

Tuesday, Nov. 9, 2010 ... The President of the Saharawi

people announced to the population that they are being asked to show restraint

and continue to hold to peaceful actions, as they have done since 1991.

Tuesday, Nov. 9, 2010 ... Negotiations which were

scheduled to be held between Morocco and the Saharawi were encouraged to

continue by the Saharawi President, even though his people were under Morocco’s

attack. The Saharawi negotiations representatives returned to the table, but

finding a continued, entrenched stand by Morocco, negotiations ended.

Wednesday, Nov. 10 ... Our American team is living amongst

a people in the refugee camps who are receiving phone calls from their family

members in the homeland, hearing the terror in their voices as they describe the

brutality they are experiencing at the hands of Moroccan troops, pleading for

help. Men and women are being

beaten, youth are being physically taken from their homes, bodies are decaying

in the street because the Saharawi cannot get out to bury them. There are a

growing number of toddlers found wandering around, unable to express what has

happened to them, and their parents’ whereabouts are unknown. Today, 150

Saharawi are missing, 11 dead, and over 700 injured. [From what I can gather,

the first 11 people to die were Moroccan police officers; it seems likely that

the violence escalated as the Moroccan police tried to identify and arrest the

men who had killed their fellow officers. There are pictures of men stoning the

corpses of dead officers and urinating on them. While I can understand the anger

the police must have felt, I cannot ignore the fact that the injustices suffered

by the Saharawi helped create the conflict.]

Wednesday, Nov. 10 ... Frustration, anger and rage have

pushed the Saharawi in the camps to their own breaking point of patience for any

justice. They cannot bear doing nothing, knowing their families are living in

horror. The governments’ plea for further patience may not be able to restrain

the anger that has built inside this peaceful people since they were forced from

their homes in 1975. As Believers in the God Who Sees and the God of Justice and

Mercy, we are asking you to urgently take action to bring this story to the

awareness of the United States.

Saturday, Nov. 13, 2010 ... Here is an update Janet

wrote just before leaving Saturday night on what we know about the Saharawi: Situation

... URGENT ... URGENT ...

Events are escalating in the Saharawi refugee camps.

Each day there have been more and more reports coming into families in the camps

via cell phone communication from the occupied homeland families. Some of that

information is as follow:

No known journalists remain in the area.

37 identified bodies discovered in a mass grave near the

now-destroyed protest camp outside Layoune. Many more bodies remain in the

streets, unable to be identified by families due to their inability to come out

of hiding.

Over 4000 have been injured.

Frantic messages from terrorized family members in

Layoune continue to pour into the camps via cell phone contact with their

families, often from women pleading for help from the refugee population.

Screams and crying have been replayed on the radio station throughout the camps.

The effect on the refugees is wrenching.

Eye-witnesses in the area outside Layoune report seeing

Moroccan helicopters dropping bodies into the sea, clothed in the traditional

blue robes of the Saharawi.

Moroccan civilians clothed as Saharawi have been armed

by Morocco with pistols and knives, and encouraged to attack and kill Saharawi

civilians, who remain unarmed. This has heightened the terror of the

already-panicked Saharawi, now unable to easily identify who might be a

dangerous person.

The number of dead continues to mount, including very

young children and the elderly.

The number of disappeared individuals is over 2000. Most

of the dead who can be identified are those on the list of disappeared.

More than 2000 were arrested.

Last night 6 were judged in court, one of them a young

man who had visited the refugee camps in the past year.

In the refugee camps: Today, Saturday, Nov. 13, larger and growing

demonstrations are taking place, mainly by young men, demanding to go to war

against Morocco. They are completely disillusioned toward any peaceful means

after growing up in the past 20 years of cease fire, during which no progress

has been made to give the Saharawi their chance for a referendum. They want to

stop the killing of their family members on the other side of the land-mined

berm and to have their country's freedom from Morocco’s cruel oppression. The

sounds of caravans of cars and trucks filled with shouting young people have

filled roadways as they travel camp to camp, adding more and more cars of young

people to their protest. This has been going on the past 3 nights, and all day

today.

The Saharawi President announced to the UN that if there

is no significant action taken by the UN or the world community by this coming

Tuesday, he cannot be responsible for what may happen as his people approach the

brink of taking matters into their own hands against Morocco. Nov. 14 marks the

anniversary in 1975 of the agreement made between Morocco, Mauritania and Spain

to take control of Western Sahara, dividing it and its resources between the

three countries. At that time, Western Sahara had been fighting to gain its

independence from Spain, under which the Saharawi homeland had been colonized

since the 1800′s.

This further deepens the wounds of the Saharawi people, who have chosen to

pursue peace until a resolution could come through the UN’s promise of a referendum.

[The situation sounds very similar to that of Palestinians who live under the

thumb of Israel. People who are constantly denied equal rights and self

determination are not going to be happy. When the people in power respond with

crushing force, things just get worse. Those of us who advocate equal rights for

everyone have to understand that large-scale, systematic injustices inevitably

lead to large-scale violence on both sides of a conflict.]

Algerian News

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 20, 2010

CANARY ISLANDS (Spain)—Spanish activist Isabel Terraza

and Mexican activist Antonio Velazquez reported their testimonies on the

"genocide" to which Sahrawi civilians in Gdem Izik camp by the Moroccan forces,

the Sahrawi news agency (SPS) reported. The Spanish daily "El Periodico"

published Thursday testimonies of the Spanish activist in which she confirmed

that it "was difficult for us to see the Sahrawis massacred while the Spanish

government is careless," noting that she remained hidden several days in a house

"where we heard inhabitants crying and yelling while being kidnapped and houses

searched." "I have seen an ambulance full of corpses," she affirmed while

presenting a video as proof.

Afrol News

(also reported Novembre 11th, 2010 by Free Italian Press)

"Massacre" and purges ongoing in Western Sahara

10 November—At least 11 Sahrawis have been shot dead

by Moroccan troops storming a camp of protesters. Sahrawi sources talk of 36

civilians being shot. Moroccan troops keep raiding Western Sahara cities,

arresting young Sahrawi men.

Around 20,000 Sahrawis—the original inhabitants of the

Moroccan-occupied territory Western Sahara—for weeks had camped outside the

territory's main cities to protest the Moroccan occupation and systematic human

rights abuses. Moroccan troops reacted by cutting off supplies of food and water

to the tent cities.

Since Monday, however, Moroccan armed security forces

have attacked the protesters, raiding the camps using real ammunition, tear-gas

and high-pressure water cannons. Sahrawis resisting the destruction of their

tent cities were shot at.

Hundreds of protesters reportedly have been arrested by

the Moroccan army and riot police, many of which have been taken to Moroccan

territory, according to Sahrawi sources. The same sources claim police are using

torture interrogating the detained Sahrawis.

Many of the Sahrawi protesters fleeing the Moroccan

attack on their camps however continued their riot in the towns of Western

Sahara. Especially the capital, El Aaiun, since Tuesday has been embattled.

Protesters are setting up road blocks, igniting fires and throwing stones at the

police.

Moroccan troops and riot police have flocked to the

occupied territory, answering the protests with gunfire. According to sources in

El Aaiun, the death toll is steadily rising. They claim to have counted 28 dead

bodies only around the tent site outside El Aaiun, among them a 7-year-old boy,

with 8 more Sahrawis having been killed in the following riots in the city of El

Aaiun.

Official Moroccan sources meanwhile claim that six

members of national security forces have been killed by the rioters.

Sahrawis in El Aaiun meanwhile report to Afrol News that

Moroccan troops are going from house to house in the city, detaining every young

Sahrawi man they can find. "The police and gendarmes are looking for young

Sahrawis in general. Additionally, they have a list of activists they want to

arrest," the source said. Human rights activists were among those arrested.

Another source in El Aaiun reports large Moroccan troop

concentrations in the Sahrawi capital. Helicopters were constantly in the air,

assisting the military and police operations.

The exiled government of Western Sahara has urged the

UN, which has a peacekeeping mission (MINURSO) stationed in the territory, to

act against the violent repression of the Sahrawi riot. The Sahrawi government

fears that Morocco will use the riot as a pretext to kill or detain large

numbers of Sahrawis opposing the Moroccan occupation.

The Sahrawis are calling on the UN Mission to at least

monitor and register human rights violations during the riot. But MINURSO

remains the only peacekeeping mission without a mandate to monitor human rights.

Whilst the Sahrawis have repeatedly called for human rights monitoring, Morocco

opposes this. Previous attempts to implement human rights monitoring within the

UN Security Council were blocked by France. [Why are France and Morocco blocking

attempts to monitor human rights abuses?]

Meanwhile, the "massacre" of Sahrawis by Moroccan troops

has caused world-wide protests. Pro-Sahrawi groups are in the process of

organising protest marches. Human rights groups demand an end to the Moroccan

operation.

The current clashes in Western Sahara are the most

violent since a ceasefire between Morocco and the Sahrawi government was agreed

upon in 1991. The ceasefire was to lead to a referendum over Western Sahara's

possible independence and the stationing of MINURSO to overseen the ceasefire

and referendum.

Algerian News

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2010

November 8 massacre marks last moments of Moroccan occupation, says Sahrawi

president Bir Lahlou (Western Sahara). Mohamed Abdelaziz, President of the

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) and Secretary General of the Polisario

Front, said "the massacre committed on November 8 by the Moroccan occupation

against the Saharawi people marks the last moments of the Moroccan occupation."

In a message to the population of El Ayun busy on the occasion of the

celebration of Eid El Adha, the Saharawi President stressed that the latest

Moroccan attack "shows all the features of historical events that make a

difference in peoples' struggle for freedom and liberation," the Sahrawi Press

Agency SPS reported Tuesday. President Abdelaziz added that the massacre of

November 8 paved the way for "relentless campaign of ethnic cleansing, lawless

arrests, mass abductions and torture of Sahrawi civilians, out of sight of

observers, the independent press and international organizations which, in turn,

have not been spared the humiliation of Moroccan occupation in Moroccan

airports." [The fact that Morocco expelled journalists and has been blocking

attempts to monitor human rights abuses makes it seem Abdelaziz has a case. When

I factor in other things, such as Morocco jailing and allegedly torturing female

human rights activists, it's difficult not to conclude that Morocco has helped

create a lot of misery for both sides.]

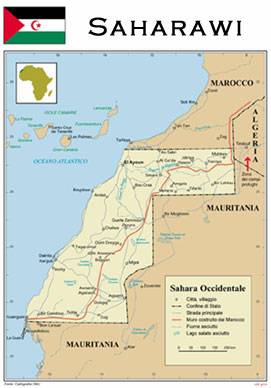

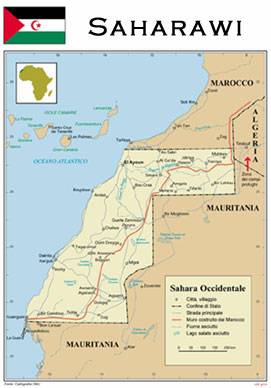

Background Facts, Drawn from Wikipedia and Other Sources

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic is a partially recognized state that claims

sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara, a former Spanish

colony. SADR was proclaimed by the Polisario Front on February 27, 1976 in Bir

Lehlu, Western Sahara. The SADR government currently controls about 20-25% of

the territory it claims. It calls the territories under its control the

Liberated Territories or the Free Zone. Morocco controls and administers the

rest of the disputed territory and calls these lands its Southern Provinces. The

SADR government considers the Moroccan-held territory occupied territory, while

Morocco considers the much smaller SADR held territory to be a buffer zone.

Mohamed Abdelaziz comes from a Sahrawi Bedouin family which belongs to an

eastern Reguibat subtribe that historically migrated between Western Sahara,

Mauritania, western Algeria and southern Morocco. As a student in Moroccan

universities in the 1970s, he gravitated towards Sahrawi nationalism, and became

one of the founding members of the Polisario Front, a Sahrawi independence

movement in Western Sahara which launched an armed struggle against Spanish

colonialism in 1973. Since 1976 he has been Secretary-General of the

organization, replacing Mahfoud Ali Beiba, who had taken the post as interim

Secretary-General after El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed was killed in action in

Mauritania. Since that time he has also been the president of the Saharawi Arab

Democratic Republic (SADR), whose first constitution he was involved in

drafting. He lives in exile in the Sahrawi refugee camps in the Tindouf Province

of western Algeria. His brother is Mohamed Lahbib Erguibi, a lawyer for many

Sahrawi human rights defenders such as Aminatou Haidar or Naama Asfari (the

former "disappeared" in Moroccan prisons between 1976 and 1991).

Abdelazizis considered a secular nationalist and has steered the Polisario and the

Sahrawi republic towards political compromise, notably in backing the United

Nations' Baker Plan in 2003. Under his leadership, Polisario also abandoned its

early Arab socialist orientation, in favor of a Western Sahara organized along

liberal democratic lines, including expressly committing it to multi-party

democracy and a market economy. He has consistently sought backing from Western

states, notably the European Union and the United States of America, but so far

with little success.

The Organization of African Unity seated Western Sahara

for the first time in 1982, despite Morocco's vehement objections. In 1985,

Abdelaziz was elected vice president of the OAU at its 21st summit, effectively

signalling that Western Sahara would be a permanent OAU member in spite of the

controversy. In 2002, he was elected vice president of the African Union, at its

first summit.

There is some criticism against him from within the

Polisario for preventing reforms inside the movement, and for insisting on a

diplomatic course that has so far gained few concessions from Morocco, rather

than re-launching the armed struggle favored by many within the movement. The

most prominent of these opposition groups is the Polisario Front Khat al-Shahid,

which states that it wants to restore the legacy of his predecessor, El Ouali.

Abdelaziz has condemned terrorism, insisting the

Polisario's guerrilla war is to be a "clean struggle" (that is, not targeting

private citizens' safety or property). He sent formal condolences to the

afflicted governments after the terrorist attacks in New York City, Madrid,

London, Kampala and notably also to the Moroccan kingdom after the al-Qaida

strikes in Casablanca. Also, as head of the SADR, he has signed the OAU

Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism at the 36th summit in

Algiers, the Dakar Declaration against Terrorism,

and the additional Protocol to the previous OAU's Convention on Terrorism at the

3rd session of the Assembly of the African Union in Addis Ababa.

In 2001, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. In

December 2005, as leader of the Polisario Front, he receive the Human Rights

International Prize, given by the Spanish Pro-Human Rights Association.

Oral History in the Palestinian and Sahrawi Contexts: A Comparative

Approach [1]

by Randa Farah

Notwithstanding the specific features of the Palestinian

case, many aspects of al-Nakba, or the Palestinian catastrophe have parallels in

contemporary history.[2] One important but neglected case that lends itself to

comparative research is the struggle of the people of Western Sahara for

self-determination. Palestinians and Sahrawis have been denied their political

rights that derive from the fact that they are nations. However, there is a

fundamental difference between the two cases: Zionism expelled the Palestinian

inhabitants in order to replace them with Jewish settlers on expropriated

Palestinian land.

As for the

Moroccan regime, it aims at annexing Western Sahara and assimilating Sahrawis as

Moroccan citizens; it rejects the Sahrawi right to self-determination, which

according to the UN Charter means Sahrawis have the right to establish their own

state, if such is the will of the nation expressed in a referendum. In light of

the above, I will discuss a few themes based on oral histories and narratives I

collected while conducting research in Palestinian and Sahrawi refugee camps[3]

mainly to situate oral history in relation to the national project, and to

outline how Palestinian and Sahrawi refugees reproduce the concepts of homeland

and their imagined return. The limitations set for the article unfortunately do

not allow me to elaborate on any of the points raised here, or to include

excerpts from the life-histories. However, I think it is important to mention

some of the issues I observed in the Sahrawi case that have resonance in the

Palestinian context: a) the reshaping of gender and generational relationships

in the context of prolonged conflict and displacement; b) the Moroccan ‘Wall of

Shame’ ironically built upon the advise of Ariel Sharon to the late King Hassan

II in the mid-eighties;[4] c) the creation of new realities by subsidizing

Moroccan settlers in Western Sahara; c) the autonomy plan suggested by Morocco

which has many similarities to the Oslo agreements; d) finally, forms of

mobilization, organization and resistance (including the role of youth in the

two Intifadas) in both national liberation movements which have straddled two

centuries, and their relationship to the larger Arab world.[5]

Refugee oral histories bring stories of how individuals

and communities experience prolonged conflict and displacement to the public.

Because of this, and despite variations in socio-economic status, gender,

generation, country of refuge embedded in the accounts, each oral history

simultaneously functions as an individual and a collective history. However, by

definition, an oral account is open and incomplete in the sense that what is

articulated, remembered or silenced and forgotten depends on the context in

which it is narrated.[6]

Background to the

Sahrawi Conflict

Western Sahara

was a Spanish colony for almost a century (1884-1975). Upon the withdrawal of

Spain in 1975, Moroccan and Mauritanian forces invaded the territory, forcing

the flight of Sahrawis to the inhospitable Algerian desert. Although Mauritania

signed a peace agreement with the Sahrawis in 1979, Morocco continues to occupy

two-thirds of the territory, and adamantly rejects the idea of a Sahrawi

referendum on self-determination. In fact, Morocco claims that Western Sahara is

Moroccan territory in violation of the principle of uti possidetis applied in

decolonization cases,[7] the UN Charter, several Security Council and UNGA

Resolutions, and a 1975 International Court of Justice advisory opinion[8].

Morocco describes the Polisario[9] as a ‘separatist’ movement, yet its

underlying aim has little to do with its ideals for unity. Rather, Morocco’s

interest is in controlling the rich phosphate deposits, abundant fisheries along

the Atlantic coast, and a large potential of oil and gas underneath the sand and

waters of Western Sahara.

In arid Algerian

desert camps built on sand,[10] the Polisario established the Sahrawi Arab

Democratic Republic (SADR).[11] The state-in-exile proceeded to implement a

National Action Program directed at transforming the refugees into citizens

capable of leading their own future nation-state upon their return to Western

Sahara. However, neither SADR nor the refugees anticipated that their exile

would last for three decades and that the referendum would have as much

substance as a desert mirage.

Oral History and

the Nation: Subaltern, Hegemonic and as Established Tradition

Palestinian

society has a written record of its past, this despite its dispersal, the

Zionist attempt to destroy its historical record, and the lack of centralized

state institutions. At one level of analysis, the Palestinian

written/professional or official record is described as hegemonic for its

emphasis on the elite and its marginalization of the poorer segments of society.

Consequently, oral history increasingly became a focus of research to capture

the experiences of the poor, including refugees. Although it is not possible to

conflate the Palestinian hegemonic meta-narrative of the past with that of

subaltern classes, both are inseparably entangled and occupy the position of the

subaltern in relation to a dominant Zionist colonial historiography.

The Oslo context

gave impetus to an upsurge in projects aiming to document Palestinian

experiences before and during al-Nakba, countering the Oslo agreements which

framed the conflict and its resolution upon the 1967 Israeli occupation, thereby

deliberately circumventing the 1948 war and its consequences. Thus, oral

histories of Palestinian refugees pose as a discourse of remembering against

omission implied in the Palestinian Authority’s official policies (despite

lip-service to UNGAR 194), and reaffirming they still have land claims,

political and legal rights in the 1948 territories.

Unlike the

Palestinians who prior to the al-Nakba were a settled agricultural population,

Sahrawi tribes were mobile pastoralists[12] who did not have a written

historical record,[13] but did have an established oral tradition transmitted

through narration, poetry and story-telling. However, the conflict necessitated

reconstructing a Sahrawi official history in a coherent manner to counter

Morocco’s claims that they do not have a distinctive national past, and to

educate younger generations on the basis of national—not tribal—affiliation

and belonging.

Thus, when asked

to distinguish a Sahrawi culture, refugees point to such factors as their

separate historical experience shaped by Spanish colonialism as opposed to that

experienced by other North African countries colonized by the French; their

specific Arabic dialect called Hassaniyyah;[14] their mode of livelihood; food,

dress, songs and the status of Sahrawi women.[15]

In 1991 a

cease-fire came into effect and the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in

Western Sahara (MINURSO) was deployed with the purpose of administering the

referendum. Refugees eagerly began to prepare Sanadeeq al-Awda (suitcases of

return), believing they were returning to participate in the referendum which

the UN planned to implement in January 1992.[16] However, Morocco succeeded in

endlessly obstructing the process, and the suitcases became reminders of

international betrayal for failing to pressure Morocco to abide by Security

Council and UN Resolutions.

In light of the

above, it is not surprising that oral histories of Sahrawi refugees collected

more than a decade after the 1991 cease-fire, reveal growing public criticism

and pressure on Polisario-SADR to resume armed struggle, especially by

unemployed, impoverished and educated youth who linger wasting their years in

the scorching desert, as they say just ‘drinking tea.’ However, similar to the

effects of the Palestinian Intifada, the Sahrawi Intifada[17] within the

Moroccan occupied territory which began on the 21st of May 2005 became the focus

of solidarity activities between the outside (refugee camps) and the inside

(Western Sahara) reawakening nationalist sentiments.

The oral

histories of Sahrawis also map out how they situate their political and cultural

identities in the context of the Arab world. Sahrawis are an Arab and Muslim

people. However, refugees express anger towards Arab governments, and underscore

their Sahrawi and African identity. This is not surprising considering that most

Arab countries know little of their struggle and most Arab governments have

sided with Morocco, while African states including South Africa and Kenya have

recognized SADR as their legitimate state.

Narratives of the

Homeland and Return

For Palestinian

refugees of rural origins, their pre-1948 original village land and a ‘peasant

way of life’ represent continuity, stability and contiguity within a familiar

Palestinian landscape, upon which they carried out specific (gendered) tasks and

mapped their social identities in elaborate genealogical charts. For city

dwellers, an urban culture, the neighborhood and family house are the loci of

memory and personal history.

The Palestinian

return was always a distant vision (Swedenburg, 1991) and little attention was

given to the shape and concrete form of the future society after liberation.

Consequently, the form of remembering Palestine strongly reshaped the

conceptualization of the future return: a collective return to an original land,

village and place. Thus, in the oral histories recorded shortly after the Oslo

agreements, 1948-refugees did not consider that the return to a Palestinian

state as citizens in the West Bank and Gaza fulfilled their dream/right of

return. In fact, many of the refugees living in camps in Jordan considered a

‘return’ to a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza but not to the

original village as another form of displacement.

The oral

histories of Sahrawis resemble those of Palestinian refugees, including a

narrative trope that is reconstructed around contrasts: as before and after the

Moroccan ghazu (invasion) which had resulted in their mass flight in 1975

referred to as al-Intilaqa (departure) a term equivalent to the Palestinian

al-Hijra or al-Nakba. These oral narratives depict pastoral nomadism as central

to the Sahrawi cultural ethos and nationalist discourse, just as the rural

hinterland and the fallah (peasant or farmer) informed Palestinian nationalism,

despite the fact that new generations were born in exile and many had lived in

urban centers even prior to their displacement.

For Sahrawi

refugees of all generations the historical homeland is remembered as a landscape

where they were free, dignified nomads and warriors who moved from place to

place following the rain and greener pasture. However, movement and settlement

are specified as along familiar and known routes, wells, streams and hills,

which took on more significance as Sahrawi territory in the context of the

anti-colonial struggle and their displacement. This attachment to Sahrawi

territory counters the popular conception that nomads or Bedouins are not

attached to national territories, because their mode of livelihood implies

crossing between geo-political boundaries.

Unlike

Palestinian refugee oral histories of return which focus on the land and

original village, Sahrawis center their imagined return on the independent

state. This is partially due to the nature of the conflict, wherein Morocco is

willing at best to accept an autonomy, while Sahrawis aspire for sovereignty.

However, the yearning for their own dawla (state), an objective prevalent in

Sahrawi oral histories, may also be attributed to the role of the Polisario-SADR

in mobilizing for the future on the basis of citizenship, and upon modernist

ideals of development and progress.

SADR’s National

Action Program required collective mobilization and participation at all levels.

This process involved administering camps as if they were provinces, districts

and municipalities, and the establishment of ministries, popular committees,

national unions, schools, hospitals, etc. Thus, the Polisario-SADR took over

many of the functions previously carried out by the family and tribal freeg,[18]

initiating fundamental social transformation. The aim of SADR was to pave the

way for the return of refugees, which was outlined in the UN sponsored peace

plan ‘as a stage necessary for the completion of a peace process’ (Bhatia

2003:786).

In conclusion, I

would like to point out that research outside the Palestinian case is not only

theoretically interesting, but is important to draw lessons in forms of

resistance and political struggle. One issue that stands out here is the

importance of collective mobilization around a strategic vision, and the

conditions that promote or challenge popular consent. For both peoples, the hope

of return has not vanished despite decades of displacement and it is clear that

such a return is imagined as a collective one based on national rights. However,

for Palestinians the past informs the imagined future, wherein the expropriated

land and property lost in 1948 are yet to be reclaimed and returned. For Sahrawi

refugees, sovereignty in the form of a state is central in their discourse of

return. What is certain is that despite decades of overwhelming power and

repression imposed on these two stateless populations, their forms of struggle

have changed, but not silenced.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. 2006. “Report 2006,” <

http://web.amnesty.org/report2006/mar-summary-eng>.

Bhatia, Michael. 2003. 2003. “Repatriation under a Peace

Process: Mandated Return in the Western Sahara.” International Journal of

Refugee Law. 15 (4): 786-822.

Farah, Randa. 2003. “Western Sahara and Palestine:

Shared Refugee Experiences.” Forced Migration Review. Oxford: Refugee Studies

Centre with the Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project. January, 16:

20-23.

‘The Significance of Oral Narratives and Life

Histories.’ Al-Jana: The Harvest: File on Palestinian Oral History. Rosemary Sayigh, ed., Beirut: Arab Resource Center for Popular Arts, pp 24-27.

International Court of Justice, Case Summaries. 1975.

“Western Sahara: Advisory Opinion of 16 October 1975.” <

http://www.icj-cij.org/icjwww/idecisions/isummaries/isasummary751016.htm>.

Joffe, George. 1996. “Self-Determination and Uti

Possidetis: The Western Sahara and the "Lost Provinces."” The Journal of the

Society for Moroccan Studies. 1: 97-115.

Swedenburg, Ted. 1991. "Popular Memory and the

Palestinian National Past." In Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in

History and Anthropology, Jay O'Brien and William Roseberry, eds. Berkeley:

University of California Press, pp. 152-79.

Tamari, Salim. 1994. “Problems of Social Science

Research In Palestine: An Overview,” Current Sociology, 42(2):69-86.

Endnotes

[1] I would like to express my gratitude to the Sahrawi

and Palestinian refugees who allowed me to record their life-histories. I am

also grateful to the Office of the Vice-President, Research and International

Relations at the University of Western Ontario, which provided me with funds

that allowed me to conduct research in the last two years in Sahrawi camps.

[2] On the importance of comparative studies, see S.

Tamara (1994).

[3] I conducted anthropological field research in

Palestinian camps between 1995 and 2000, and the material used for this paper on

the Sahrawi case took place between 2004 and 2006, although I have been visiting

the camps since 2003.

[4] See speech delivered by Margot Kessler on 19th April

2002 during the Euromed conference in Valencia, Spain organized by the United

Left in which she stated: “Western Sahara is split in two: a 1800 kms long

military defence wall was built in the early 80's by Hassan II on the advise of

someone who will be much talked about at this conference: that is ... Ariel

Sharon.”

[5] For more information on Sahrawi and Palestinian

camps see Farah, 2003.

[6] On Palestinian oral narratives see R. Farah (2002).

[7] In 1964 the Organization of African Unity (currently

the African Union) adopted this principle which establishes the boundaries of

the colonial territories as the frontiers of newly independent states. For more

on this question see G. Joffe (1996).

[8] See the International Court of Justice. 1975. “Case

Summaries: Western Sahara: Advisory Opinion of 16 October 1975.” <

http://www.icj-cij.org/icjwww/idecisions/isummaries/isasummary751016.htm>.

[9] Polisario is the Spanish acronym for Frente Popular

para la Liberacion de Saguia el Hamra y Rio de Oro or The Popular Front for the

Liberation of al-Saqiya al-Hamra and Rio de Oro, the two regions that constitute

Western Sahara. The Polisario was established on the 10 May 1973 and led the

Sahrawi resistance against the Spanish and later against the Moroccan and

Mauritanian invasion.

[10] The nearest town to the Sahrawi camps is Tindouf, a

small Algerian border town. The camps are geographically isolated in one of the

harshest deserts, where temperatures can soar to over fifty degrees in the

summer and below zero in winter. There are no electricity lines or water pipes,

therefore most refugees rely on batteries for electricity and water tanks. This

is in contrast to Palestinian camps located in or near major urban centers in

the Middle East.

[11] The Sahrawi state was declared in exile in the

refugee camps in Algeria on the 27th of February 1976 and is recognized by over

eighty countries.

[12] The Sahrawis subsidized their livelihood with

seasonal cultivation, trade, fishing and towards the end of the Spanish colonial

era, many were forced to settle in urban centers working as cheap labor in

colonial enterprises, primarily in the phosphate industry and the construction

of roads.

[13] Sahrawis often hired a Mrabet or Koranic teacher

who taught reading and writing to the children of a freeg (see note xviii). The

Mrabet moved with the freeg and was usually paid in kind for his services.

[14] Sahrawis are the descendents of tribes who migrated

to North Africa during the Islamic conquest and intermarried with local Berbers,

one of these tribes was Bani Hassan, hence the term Hassaniyya.

[15] Sahrawis point to the fact that unlike the

situation of women in surrounding Arab countries, Sahrawi women are highly

respected (violence against women is absent and abhorred among Sahrawis),

autonomous and have equal rights enshrined in SADR’s constitution.

[16] Many Sahrawis informed me they were so sure they

were returning that they sold all their meager belongings.

[17] See Amnesty International

http://web.amnesty.org/report2006/mar-summary-eng, which stated that popular

protests were met with ‘excessive use of force’. Many Sahrawis have been killed,

injured or imprisoned as a result of their demands for self-determination and

human rights. For more information on the Sahrawi Intifada see

[18] The freeg or group is the basic socio-economic unit

in the Sahrawi tribal society made of three to five tents or families who

cooperated in carrying out daily functions.

Published in Oral History—Uncovering Palestinian

Memory (Winter 2007)

Social sharing

Madrid, Jan 05,2010 (SPS) The Spanish judge, Baltasar

Garzon, will travel in the coming days, to the Saharawi refugee camps to

interview thirteen Saharawi witnesses in connection with his investigation of

the genocide and war crimes "perpetrated by politicians and Moroccan troops in

Western Sahara since October 1975," announced Monday the Spanish radio (COPE).

"In refugee camps, Judge Garzon will hear a total of

thirteen Saharawi witnesses accusing 32 political and Moroccan military chiefs

on war crimes and genocide against the Saharawi people,"since 1975, when the

Morocco military has invaded Western Sahara, said the radio program "La Manana."

The famous judge of the National Court, the highest

Spanish criminal proceeding, had agreed in September 2006 a complaint of Sahrawi

citizens and several Spanish and Sahrawi human rights organizations for "the

crime of genocide, murder and torture committed by Moroccan state in Western

Sahara."

These include the Association of Families of Sahrawi

Prisoners and Disappeared (AFAPREDESA), the Federation of Spanish Institutions

for solidarity with the Saharawi people, the Coordination of Spanish

associations of solidarity with the Saharawi people and the Spanish Association

for Defence human Rights.

Judge Garzon, who said he was "competent" to investigate

the complaint had already auditioned in December 2007 in Madrid, four Sahrawi

witnesses, thereby initiating a formal investigation procedure on the genocide

against the Saharawi people.

A lawyer originally filing the complaint had stated,

"International crimes mentioned include genocide, torture, forced disappearances

of people, abductions, killings and injuries.

He explained further that "in the complaint are recounted the circumstances in

which were perpetrated these acts, how 40,000 Saharans had fled their country,

how they were kidnapped, tortured, sometimes thrown from helicopters into the

void, how countless crimes were committed against them and all acts of

genocide."

The complaint also notes that the massacre of the

Saharawi people has extended over several years during which it was subjected to

domination by a foreign power preventing it from "freely exercise their right to

self-determination, recognized by the resolution 1514 General Assembly of the UN

in December 1960."

The plaintiffs also claimed that "since October 1975

until now the Moroccan army had a permanent violence" against the Saharawi

people in a war of invasion requiring 40,000 Saharawis to abandon their homes

and flee into the desert where they were "pursued and shelled by the invading

forces with napalm, white phosphorous and cluster bombs." (SPS)

Copyright © Sahara Press Service. All Rights Reserved

Activists hiding in Laayoune denounce 'genocide'

Staff—11/15/2010 | eitb.com

Spaniard Isabel Terraza and Mexican Antonio Velázquez

released a video in which they call on the UN for urgent intervention.

The Spanish pro-Sahrawi activist Isabel Terraza and her

Mexican partner Antonio Velázquez, who have spent the last few days hiding in

the Sahrawi capital of Laayoune, have publicly censured the "genocide being

committed by the Moroccan regime" on the Sahrawi people, for which they urge

immediate intervention from the UN.

In a video-communication sent to the media and uploaded

onto YouTube, the two activists request that the Security Council uphold the

human rights of the Sahrawi population, urge the International Red Cross to

enter the territory in order to attend to the victims and call on the

international community to condemn the assault being carried out on the civilian

population.

"This is an international emergency and it is necessary

that all the international organisations stop this massacre," the activists

declare.

In the video, which lasts two minutes and was filmed on

Sunday in Laayoune, Terraza and Velázquez say they are "witnesses to the

genocide currently being committed by the Moroccan regime on the Sahrawi

civilian population in the occupied capital of Western Sahara."

Terraza cites the "violent repression being exerted on

the Sahrawi people" in the streets and in their homes, since the evacuation of

the Agdaym Izik last November 8th.

Furthermore, the activists accuse the "occupying Moroccan regime" of not

allowing the press to enter "in order to hide the atrocities," adding that "they

want to kill us, because we are bearing witness before the whole world."

"We have been hiding out in the city of Laayoune for the

past few days but, like us, thousands of Sahrawis are in the same situation or

worse because police and the Moroccan military are entering their homes by

forces; they then torture them, and many die as a result," affirms Terraza.

Morocco is carrying out a wave of repression and torture

following last week's eviction by force of a Sahrawi camp based on the outskirts of

Laayoune.

Spanish newspaper El Mundo revealed on Monday that

Moroccan authorities are organizing colonist militia to 'hunt' Sahrawis and

colonise Laayoune.

Aminatou Haidar

أميناتو

حيدر

The following information has been excerpted from her Wikipedia page.

Awards: Juan Maria Bandres Human Rights Award, Silver Rose Award, Robert F.

Kennedy Human Rights Award, Civil Courage Prize, Jovellanos 'Resistance &

Freedom' International Award, University of Coimbra Medal

Aminatou Ali Ahmed Haidar (Arabic:

أحمد

علي

حيدر

أميناتو; born 24 July 1966 or

1967), sometimes known as Aminetou, Aminatu or Aminetu, is a Sahrawi human

rights defender and political activist. She is a leading activist for the

independence of Western Sahara. She is sometimes called the "Sahrawi Gandhi" for

her nonviolent protests, including hunger strikes, in the support of the

independence of Western Sahara. She is the president of the Collective Of

Sahrawi Human Rights Defenders (CODESA).

Aminatou spent her childhood in Tan-Tan (formerly part of the Spanish West

Africa). She now lives in El Aaiún in Western Sahara, with her two children

(Muhammad and Hayat), is divorced, and holds a baccalaureate in modern

literature.

On 21 November 1987, she became one of the hundreds of

Sahrawis who "disappeared" in Moroccan prisons. After years of torture and

interrogation (she spent her entire imprisonment blindfolded, because of which

she suffers photophobia, as well as other health problems), she was finally

released on June 19, 1991. She had been held in prison for nearly four years

without any charges or trial, in secret detention centres. The Moroccan

authorities have never provided a formal reason for her arrest and

"disappearance," but it is believed that she was targeted for peacefully

demanding the right of the people of Western Sahara to self-determination.

She was incarcerated for the second time in the Black

Prison of El Aaiún on June 17, 2005, after having been arrested in a hospital

where she was receiving treatment for injuries inflicted by Moroccan police,

during a peaceful demonstration in the Western Sahara Independence Intifada.

Reportedly she was tortured during interrogations. Amnesty International has

expressed great concern about the situation of Sahrawi prisoners in

Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, and specifically taken an interest in the

case of Haidar, expressing fear that her right to a fair trial might not be

respected, and stating that she may be a prisoner of conscience.

On December 14, 2005, Haidar was sentenced to

seven months in prison by a Moroccan court in El Aaiún. Amnesty, which had sent

an observer to cover the trial, was immediately sharply critical of the Moroccan

government, and said it was strengthened in its belief that she may be a

prisoner of conscience.

There was an international campaign for Haidar's

release supported by 178 members of the European Parliament. The parliament also

called for her immediate release in a resolution in October 2005.

On January 17, 2006, Haidar was released at the end of

her sentence. A demonstration received her in Lemleihess because Moroccan

authorities didn't allow her family to receive her in their own house. She

reportedly commented that "...the joy is incomplete without the release of all

Saharawi political prisoners, and without the liberation of all the territories

of the homeland still under the occupation of the oppressor."

After this discharge, Haidar was granted compensation of

45,000 euros from the Equity and Reconciliation Commission (IER) established by

the Moroccan government to compensate the victims of arbitrary arrest.

On November 13, 2009, Haidar was arrested on her return

to El-Aaiún for allegedly refusing to enter "Morocco" in the "Country" box on

her entry card, instead leaving the citizenship line blank on her customs form,

and writing "Western Sahara" — the disputed territory where she lives — in the

address line. She had done the same many times previously without problems. She

later declared that she was not visiting Morocco but Western Sahara. She refuses

to accept that Western Sahara is a part of Morocco. "They want to compel me to

recognize that Western Sahara belongs to Morocco," she declared to journalists

on November 14, 2009.

Haidar arrived at El-Aaiún airport from Gran Canaria in

the Canary Islands. She was with two Spanish journalists, Pedro Barbadillo and

Pedro Guillén, who accompanied her with the intention of making a documentary

about human rights abuses in Western Sahara. The two journalists were detained

for trespassing and filming in the airport without prior authorisation. The

Moroccan authorities claim that Haidar declared she was renouncing her Moroccan

citizenship and that she voluntarily signed the renunciation documents, and

surrendered her passport and national ID card. Following this alleged

renunciation, she was deported, along with the two journalists that accompanied

her, to Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. Barbadillo, who was with her when she

completed the entry documents to travel to Western Sahara, claims that the

Moroccan government's version of events is false and declared he saw her

completing the form himself. Documents that were retrieved and published in the

Spanish newspaper El País show that the Moroccan government had made three

different flight reservations for Haidar, indicating that they had planned to

expel her from the country days in advance of her actual arrival. Because they

did not know with certainty when she would be arriving, they booked seats in her

name on three different flights, so they could deport her whenever she arrived.

According to El País, Haidar informed the pilot on her

flight back to Spanish territory that she did not have documents to travel and

was being held against her will. The pilot was doubtful, but finally took off

after receiving a call from Spanish authorities. The party finally arrived at

Lanzarote about noon on Saturday evening, and Haidar sought the urgent

intervention of the United Nations Secretary General to "ensure personal

protection" and declined to leave the departure terminal at Lanzarote airport,

claiming that the Spanish authorities had kidnapped her by declining to allow

her to board another international flight (to El-Aaiún) because she was unable

to produce her passport. She was apparently entitled to travel within Spanish

territory. Mohamed Salem, a delegate of the Frente Polisario in Canarias,

claimed that she intended to remain at the terminal of Lanzarote airport, and

engage in a hunger strike in protest against her kidnap by the Spanish

authorities.

On November 17, 2009, while on hunger strike, she was told by

the Spanish authorities to appear in court on public order charges. A fine of

180 euros was imposed by the Spanish court for public order disturbance.

El País reported that a Moroccan delegation led by the

President of the Moroccan Senate, Mohamed Cheikh Biadillah, visited Spain in

early December 2009. He insisted that the Sahrawi people are fully integrated

into Moroccan society and occupy some of the highest offices in Moroccan

institutions. He insisted that no country would accept the return of a person

who had "thrown away their passport" and "has renounced their nationality."

Biadillah later met with Jorge Moragas, coordinator of

the main opposition People's Party, which intends to bring an action against the

Spanish Government, alleging it violated two articles of the law

on foreigners by implicitly assisting Morocco to force Haidar to cross the

Spanish border on November 14, 2009, in Lanzarote.

Ever since Haidar was deported, numerous actors,

writers, musicians, politicians, human rights activists and personalities have

shown support for her cause and have asked both the Moroccan and Spanish

governments to resolve the situation. In November 2009, Portuguese Nobel

Prize-winning writer José Saramago who has a home in Lanzarote, sent her a

letter of support, saying that "If I were in Lanzarote, I would be with you" (he

was away from the island) and stating "We would all be poorer without Haidar."

About Morocco he declared "Whoever is confident about its past doesn't need to

expropriate its neighbour to express a greatness that no one will never

recognize." Later, on December 1, Saramago finally met Haidar at Lanzarote's

airport to show her his "respect and admiration." He also declared that "It's

time for the international community to pressure Morocco to comply with the

accords about the Sahara."

Eduardo Galeano and Javier Bardem are among the

personalities who have asked both governments to put an end to this situation,

which they describe as an injustice. Bardem published an open letter in the

Spanish newspaper El Mundo in which he expressed his "support and

respect for the human rights campaigner and representative of the Sahrawi

people." His letter criticizes the Spanish government as "blind." Galeano has also shown his

solidarity with Haidar. He has thanked her for her "bravery." He also said in

his letter: "People like you help us confirm that a fight for another world is

not and will never be a useless passion. Thank you very much. Lots of people

love you, and I am one of them." Writer Alberto Vázquez-Figueroa also give

Haidar his support. Argentinean Nobel Peace laureate Adolfo Pérez Esquivel

asked for a "humanitarian and political exit" for Haidar, and called the Spanish

and Moroccan governments to undertake dialogue to see "in what ways could the

European Union, Council of Europe or even the United Nations intervene to avoid

a tragic outcome and try to save her life, but not at any cost."

British film-makers Ken Loach and Paul Laverty sent two

letters to newspapers, one to El País and another to The Guardian. In the first

one they draw a parallel between Haidar and Rosa

Parks. They asked the

Spanish government to guarantee her safe return home. In the second letter, they

began by referring to a collective letter sent to Juan Carlos I, asking for his

mediation with the Moroccan Sultan, and their belief that begging won't bring a

solution. Then they blamed Mohamed IV for "ignoring international standards,

human rights law and the international court of justice ... behaving like some

medieval despot" and accused him of "threaten[ing] Spain with impoverished

Moroccans across the straits, or turning a blind eye to Islamic

fundamentalists." They finally highlighted the non-violent resistance of Haidar,

and demand justice as human beings.

On December 10, 2009, a letter was sent to the King of

Spain, asking him to intercede for Haidar with Morocco. The letter was signed by

three Nobel laureates—Günter Grass, Dario Fo and José Saramago—as well as

other international personalities, including Pedro Almodóvar, Mario Vargas Llosa,

Penélope Cruz, Antonio Gala, Almudena Grandes, Carlos Fuentes and Ignacio

Ramonet among others.

On December 29, 2009, a free concert to show solidarity with Aminetou Haidar was held in Rivas Vaciamadrid, on the outskirts of Madrid, with

performances by Bebe, Kiko Veneno, Macaco, Amaral, Pedro Guerra, Mariem Hassan,

Conchita, Miguel Ríos and Ismael Serrano among others.

Ban Ki-moon and European Union leaders were seeking a means of applying some

effective pressure on Morocco. The solution, according to some diplomatic

sources, might be a US intervention that went beyond the statement it released

on November 26, 2009, in which the State Department expressed "concern" about the

health of Haidar and called for respect of her rights. According to El País, the

US finally entered the crisis, triggered by the expulsion of Haidar, by

contributing more international pressure on the king of Morocco to allow the

return of Sahrawi activist to the city where she lived with her family.

On December 11, 2009 Haidar entered her 25th day of

hunger strike in the airport of Lanzarote and Spanish Foreign Minister Miguel

Angel Moratinos announced he was to make an ad-hoc trip to Washington three days

later for talks with his counterpart. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton

spoke with Moroccan Foreign Minister Taieb Fassi Fihri, asking him to allow

Aminatou to return to her home in El Aaiun.

On December 18, 2009, following 32 days on hunger strike and a brief admission

to the intensive care unit of Lanzarote hospital, the BBC reported Haidar

returned home following interventions by the US and France. Upon her return,

Haidar was placed under house arrest by Moroccan police.

In 2005 she was nominated for the Sakharov Prize, and in

2006 she was nominated by the US branch of Amnesty International to the Ginetta

Sagan Fund Award. In May 2006 Haidar was awarded the V Juan Maria Bandres award

for Human Rights (Spain), and in October 2007 she received the European

Parliament Silver Rose Award (Austria). In February 2008, the American Friends

Service Committee announced it had proposed Haidar as a Nobel Peace Prize

nominee. In May 2008, she was awarded the Special Prize City of Castelldefels

(Spain), given by the city council. Haidar won the 2008 Robert F. Kennedy Human

Rights Award (US). In addition to the prize (which includes a financial

component), the RFK Memorial Center offers to partner with recipients in their

work. Haidar was awarded the 2009 Civil Courage Prize (US) on 20 October 2009 at

an award ceremony in New York City. In January 2010, the Italian municipality of

Sesto Fiorentino appointed Haidar as "Honorary Citizen" of the village, for her

"non-violent struggle for Liberty and Human Rights for her people." Days later,

another Italian municipality, Campi Bisenzio, decided by a majority to grant her

"Honorary Citizenship." In July 2010, another ten towns from the Italian

province of Lucca decided to give the "Honorary Citizenship" to Haidar (one of

them, Stazzema, also gave her the "Gold Medal of Resistance"). A further 20

Italian towns have appointed Aminatou Haidar as "Honorary Citizen." Haidar has

been also awarded in 2010 with the I Jovellanos 'Resistance & Freedom'

International Award (Spain), the "Liberty, Peace & Solidarity" prize on the

XXXIV "The Best of 2009" awards, given by the Spanish weekly magazine Cambio 16

& the VI Dolores Ibárruri Prize (Spain). She has been nominated again by more

than 40 European parliamentarians to the Sakharov Prize, in its 2010 edition,

and also to the "African Personality 2010" prix, given by the Nigerian newspaper

Daily Trust. Few days after, europarlamentarian Willy Meyer Pleite denounced a

campaign of letters by Morocco to avoid the concession of the prize to Haidar.

In November Haidar was awarded with the "University of Coimbra Medal, "given by

the Portuguese educational institution for her attitude and civic actuations in

defense of human rights in Western Sahara. That month she also received the

"International Prize Trojan Horse of Guacales" (Mexico) at the UNAM, during the

"Revolutionary Women's Day."

The HyperTexts