The HyperTexts

Jared Carter Interview with Michael R. Burch

Jared Carter's first collection of poems, Work, for the Night Is Coming,

won the Walt Whitman Award for 1980. His second poetry collection, After the Rain, received

the Poets’ Prize for 1995. His third collection, Les Barricades Mystérieuses,

was published in 1999. His latest book is

Darkened Rooms of Summer,

published in 2014 by the University of Nebraska Press, with an intro by Ted

Kooser, a Pulitzer Prize winner and two-term Poet Laureate of the United States.

Michael R. Burch is the founder and managing editor of The HyperTexts.

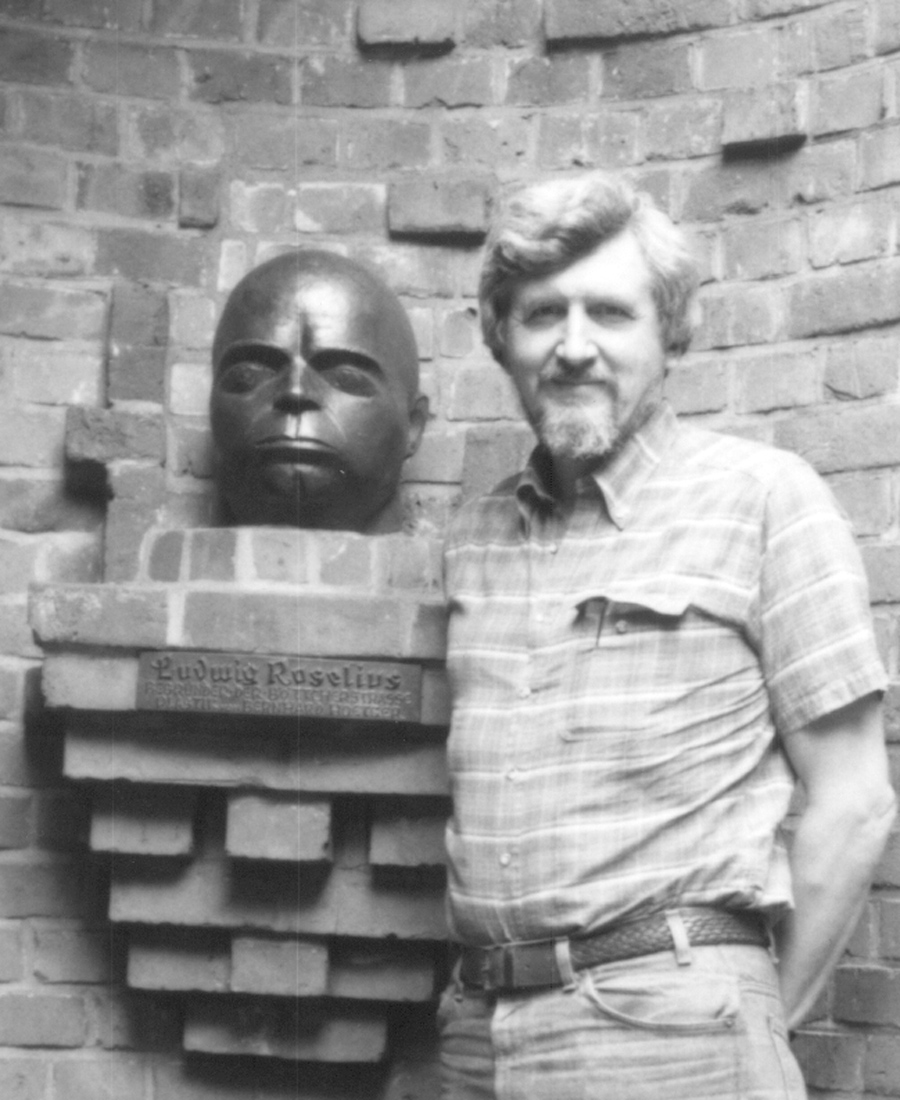

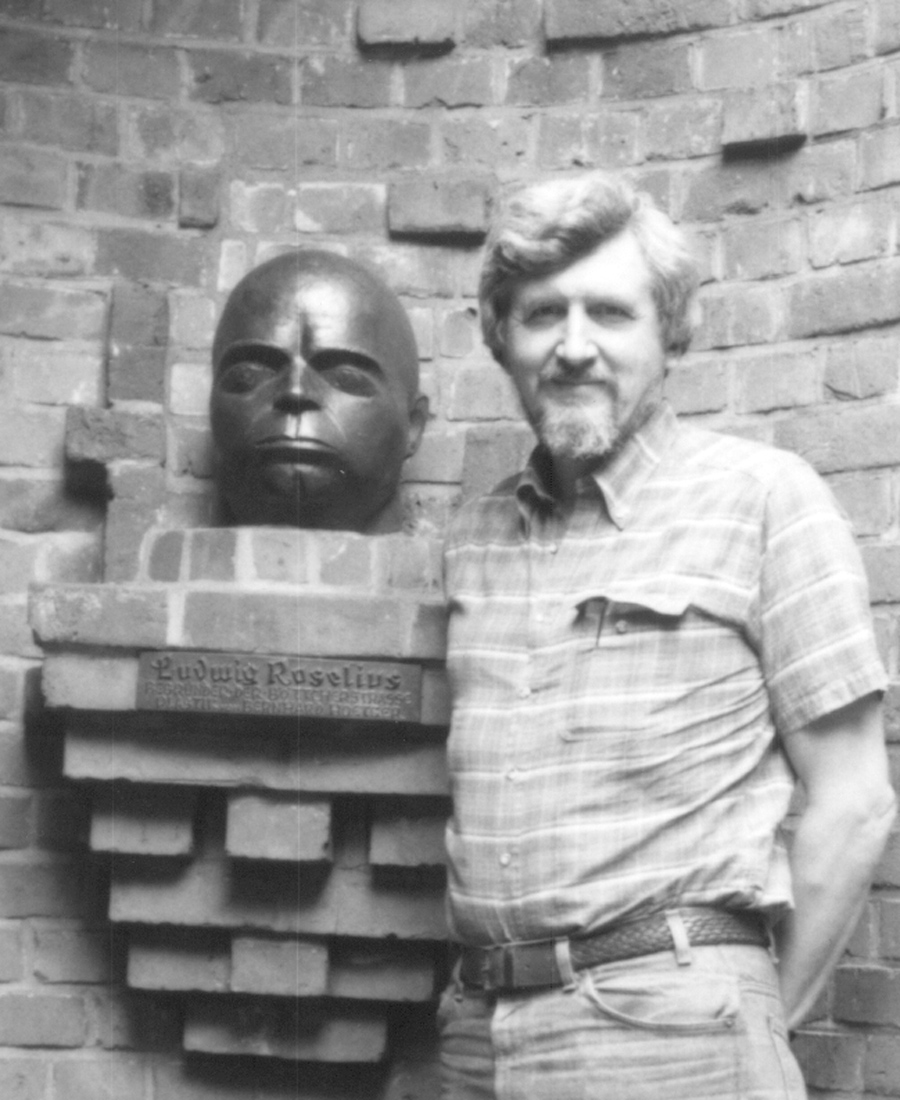

The photo above of Jared Carter in Bremen’s Böttcherstrasse district was

taken by the German visual artist Alfred Akkermann in June of 1986. The two were

en route to spend a day at the former artists’ colony at Worpswede, where Rilke,

Paula Becker, and other young artists had gathered at the beginning of the

twentieth century. The photo does not show Jared Carter standing next to the

bust of some famous German writer. Instead, the statue commemorates Ludwig

Roselius (1874-1943), a leading Bremen businessman who made a fortune after he

invented decaffeinated coffee in 1903. Roselius, a patron of early expressionist

art, was instrumental in creating the Böttcherstrasse and was denounced by

Hitler for doing so. Looking back on the photo from the vantage point of 2014,

Carter says “In the interim I have consumed so much decaffeinated coffee that

surely Ludwig Roselius must have been one of my patron saints, along with

whoever invented the doughnut and the bagel.”

MB: Jared, let me begin by thanking you for taking the time to do this

interview. My first question is why you chose

Darkened Rooms of Summer as the title

for your selected poems. I find the phrase haunting, as we normally

think of summers as being hot and bright, with the shadows of autumn and winter

lying in the future. The ancient Celts believed in a mysterious otherworld that

existed in a sort of continuum with the "real world." Were you hinting at

something like that, or did you have something else in mind?

JC: Thank you, Mike, for inviting me to share this page with you, and for

The HyperTexts’ longstanding support

of contemporary poetry. Your first question is intriguing. I’d be pleased if you

or anyone else read that particular Celtic subtext into my book’s title. But the

truth is a bit more prosaic.

I ran across the phrase in The Portable

Henry James many years ago and thought that someday I might use it on a

book. The passage in James’s journal in which it appears is memorably nostalgic,

and seemed appropriate for a “selected poems,” which involves looking back. So

an excerpt from that passage serves as the book’s epigraph. Incidentally,

James’s many supernatural stories would seem to indicate that he was receptive

to the notion of a continuum to another more mysterious world.

MB: Do you believe in such a world?

JC: I’m of two minds. As a mortal, I doubt very much that after my death I’ll be

teleporting through this or that particular wormhole. But it seems to me that

both nightly dreams and the sort of imagination that makes poems are constantly

opening onto other worlds.

MB: I find it interesting that some of the great poets and philosophers were

mystics or seemed to share the mystics' belief in a divine or transcendent unity:

Socrates, Plato, Jesus, Rumi, Blake, Wordsworth, Emerson,

Whitman, Dickinson, et al. Blake claimed that he spoke to angels and

departed saints. My friend the poet Kevin Roberts claimed to speak to angels and

even kept journals of what they told him. I've had mystical experiences myself,

and moments of clairvoyance. Have you ever had a mystical or inexplicable

experience that inspired a poem?

JC: Moments of transcendence of which you speak—such as an out-of-the-body

experience—seem to be part of human life. I’m uncertain about what labels to

give them—mystical, religious, ecstatic. For the most part they remain private

and personal, as in nightly dreams. As for my writing about them, or being, as

you say, “inspired” by them, or attempting to put them into poems—I’m not

consciously aware of doing that.

Simone Weil, no mean mystic herself, once observed that “excellence in a

particular art can be achieved exactly

in proportion to one’s ability not to think

about.” I’m not so sure about the

“exactly.” But she was on the right track. Big topics don’t always make

convincing poems.

Whitman’s small-scale epiphanies in “When I heard the learn’d astronomer” and “I

think I could turn and live with animals” seem to me more convincing than—say—Eliot’s pontifications in Four

Quartets. I believe Rilke’s best verse is to be found in the objective and

mostly impersonal poems of the two Neue

Gedichte volumes. In the Duino

Elegies he’s certainly attempting to convey a sense of boundaries fading and

worlds beyond, but I am seldom persuaded. It tends to get rather hushy and

gushy. Even squishy.

MB: I like Whitman’s small-scale epiphanies too. One of my favorite poems of his

is “A Noiseless Patient Spider.” Whitman’s idea of somehow being one with

everything, even blades of grass, makes me think of a metaphor I encountered

during my studies of the mystics: God is

the sea, and we are the waves that rise from it. Some mystics seem to

believe that ending one’s individual emanation and collapsing back into the

Great Unity will result in bliss.

But I see almost the opposite of Unity in some of your poems. For instance, the

characters in “The Pool at Noon” and “At the Art Institute” seem unknowable,

even alien. They’re powerful poems, but a bit unsettling to read. How did you

come to write them?

JC: It’s hard to remember. I think that, like Topsy, they “just growed.” I do

recall that right before I wrote “The Pool at Noon,” I had been visiting a good

friend in Lawrence, Mass.—Peter Burnham, publisher of

The Long Story, which has featured so

much of my work.

When you first get off at the Long Island Railroad station in Lawrence, you

notice all these abandoned, red-brick buildings. Miles of them along the

Merrimack River. They’re the old spinning and knitting mills from Thoreau’s day,

and from the days of the Bread and Roses Strike in 1912, and Sacco and Vanzetti.

They’re preserved, but they’re entirely empty.

There’s a lot of that red-brick desuetude in the Midwest, too, especially since

2008. A lot of manufacturing has gone south, or out of the country altogether.

“The Pool at Noon” may be a response to that change. Perhaps it whispers that even though times are tough, we’re resilient

enough to find a way through.

As for “At the Art Institute,” I first visited that collection in Chicago in the

summer of 1955, and it’s been a part of my life ever since. I’m happy to say

that over the years I’ve noticed quite a few persons in wheelchairs being shown

through those galleries. I suppose I simply worked an odd twist on the observed

phenomena.

Normally we expect other people in museums to be quiet, and when they’re not,

sometimes we’re annoyed. But there’s something tough, if unsettling, about the

old woman in the wheelchair and her son. They don’t give a damn for the refined

sensibilities of the other patrons. Or the persona’s, either. They’re on a

mission. The poem speaks of their “witnessing” and their “courage or

indomitability.”

MB: I found both poems a bit unsettling, in a good way. Another of my favorite

poems of yours is “After the Rain.” How did you come to write that one?

JC: It’s material that’s been out there for a long time—Native American

artifacts commonly known as points and projectiles, although there are larger

items to be encountered. For young Midwesterners it’s a

rite de passage to go out and look

for them. I’ve referred to that tradition in a few other

poems—“Raccoon Grove,” “Picking Stone,” “Lost Bridge”—and I’ve known several

people who have been quite successful at finding such artifacts. It’s a way of

connecting with the continent’s pre-Columbian past.

MB: Do you have a personal collection?

JC: I have a handful, but others have done far better than me in that respect. I

had the privilege of knowing the late George L. Johnson, up near Rensselaer,

Indiana, in Jasper County, who had assembled the best private collection I have

ever seen. But my own collecting specialty is bricks.

MB: Bricks?

JC: Right. Especially paving bricks, but any sort of brick that has writing on

it. Southwestern Indiana, and southeastern Ohio, have a lot of coal, and where

you find coal, you also find clay. After the Civil War there were extensive

brickmaking factories in those areas. History is written on a lot of those

bricks. So I collect them when I can.

MB: Interesting. But we’ve strayed

away from poetry. How do such activities—collecting bricks and arrowheads—relate

to your own writing?

JC: Picasso said “I don’t seek, I find.” That’s an important distinction. You

discover the best projectile points when you’re not looking for them at all.

When you’re simply out somewhere and you look down and

there it is. But of course that kind

of alertness takes time to develop. Chance favors the prepared mind. “The more I

practice,” Jack Nicklaus said, “the luckier I seem to get.”

So I don’t go out and look for bricks or intentionally search for them. Rather, I’m constantly scanning the world around me while having nothing

particular in mind. Now and then a loose brick catches my eye, usually in a pile

of debris at the side of the road. I think it’s the same

with poems.

It’s what Simone Weil meant in that earlier quote—if you start to think

“about” some current topic or fashionable idea you’ve decided to put in a poem,

or if, as in “After the Rain,” you think you already

know what you’re seeing in that

freshly plowed field, you’re probably going to miss it altogether. In either

case it’s the conceptualization itself that can lead you astray.

You have to learn how to give it up.

This is Eugen Herrigel’s suggestion in that wonderful book,

Zen in the Art of Archery.

Maybe instead of “find,” a better term is “encounter,” but even that word

doesn’t plumb the mystery. The projectile point is already there, so is the

paving brick, so is the eighteenth green, so is the poem. You shouldn’t seek

them—go after them intentionally—and you don’t really get any credit for

finding them. Instead, they reveal themselves to you.

When LeBron is “in the zone,” he doesn’t aim for the basket; the basket reveals

itself to him. The ball is simply their way of recognizing each other. It’s like

the collapse of two entangled particles, even though they are light years apart.

(Although LeBron operates at almost such distances.)

As in the closing words of “After the Rain,” such moments become “glittering and

strange.” Ask anyone who knows about gathering morels. You’re so happy that it’s

spring and you’re out in the woods again, you forget about why you came. You

don’t find them; they find you.

MB: Isn’t this simply a

different answer to a question I asked earlier—about mysticism, or the

possibility of mysterious other worlds?

JC: I don’t think so, because much of mysticism seems to me to boil down to

essentialism. There is this assumption that other worlds exist; we’ve just got

to pick the right world, and then find the right key to unlock the door, whether

it’s drugs, alcohol, sex, prayer, or meditation. I don’t believe that. I don’t

know what’s out there. But it isn’t separate from me; rather, I’m a part of it.

I’m an existentialist, then, with little interest in the various claims for

essentialism. There’s just me and some sliver of knapped stone out there in the

field, hidden by the furrows. It might reveal itself to me, it might not. If

someone wants to hang a label on that state of affairs, or rationalize it or

philosophize about it, that person has my blessing.

But it’s still just a piece of stone, and I’m still standing in some farmer’s

field. What inheres in the artifact, what might inhabit it, imaginatively, is

far more than I can say. But the business of poetry is to go ahead and try to

say it anyway.

MB: If the morels can find the gatherer and the basket can reveal itself to

LeBron James, it seems to me that you’re describing something mysterious and

mystical—as if you think the universe is alive, or that the Earth has some

form of consciousness.

JC: Believing the contrary—that it’s dead and inert, and exists only to be

ravaged and plundered—is what has

gotten us into our present environmental and atmospheric pickle. I don’t know

whether it’s dead or alive; those are extremes of the human predicament, not of

the universe at large. The earth is somewhere in between. I believe it’s at

least aware, and connected in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Although of course such awareness is

commonplace in many traditional cultures.

We can develop ways to participate in this awareness, or we can stick our heads

in the sand. What’s around us is full of the kind of “spooky action at a

distance” that Einstein disparaged. A theory of quantum gravity, if we ever

manage to achieve one, may possibly help us come to terms with such spookiness.

Recently Lyle Daggett, a poet up in Minneapolis who has a first-rate blog,

quoted from essay entitled “A Professional Secret” by the critic John Berger.

The latter is talking about this spooky sort of reciprocity as visual artists

sometimes experience it. His explanation improves upon what I’m trying to

suggest here. “When the intensity of looking reaches a certain degree,” Berger

says, “one becomes aware of an equally intense energy coming towards one,

through the appearance of whatever one is scrutinizing.”

He goes on to describe this sort of “coming at you” experience or awareness

almost in terms of a ball being exchanged:

The encounter of these two energies, their dialogue, does not have the form of

question and answer. It is a ferocious and inarticulated dialogue. To sustain it

requires faith. It is a burrowing in the dark, a burrowing under the apparent.

The great images occur when the two tunnels meet and join perfectly. Sometimes

when the dialogue is swift, almost instantaneous, it is like something thrown

and caught.

MB: Are there any poets, past or present, who exemplify

this kind of reciprocal connectedness for you?

JC: Sure, there are a lot of them,

and that’s why those of us who like lyric poetry like it so much. Because it

draws us into these strange, glittering moments of epiphany and revelation.

Spookiness, even.

MB: Can you name names?

JC: Li Bai and Du Fu, to pick only two out of hundreds. I’d rather name poems.

But a poet who has particularly impressed me recently, thanks to

The HyperTexts, is Richard Moore .

MB: Richard Moore is certainly a poet worth paying attention to, in my opinion.

I got to know him pretty well, and it was my honor to publish his last essay, “A

Life.” What did you notice about his work?

JC: He’s that rare poet who is simultaneously a genuine human being and an

immensely skilled craftsman. His essays and critical pieces, many of which you

have been good enough to place online, are quite good. But some of his poems are masterful. I don’t say that because they happen

to be in traditional forms. I say it because they strike me as being extremely

well done.

Of course the best of his contemporaries understood this; he received

compliments from Richard Wilbur and Howard Nemerov, among others, and when he

died, tributes poured in from all over the map. Some of his verse is light, but

in that regard I think he’s right up there in the same class with Dorothy Parker

and Ogden Nash.

MB: Care to cite a particular poem?

JC: Out of so many? Well, O.K., take a look at one of my favorites, “Oswald

Spengler.” Right away, with such an oddball title, you know this is going to be

strange, and Moore does not disappoint:

He said that mathematics was an art

and won my heart;

that cultures die; the sign of death, a Caesar—

O, what a teaser!—

and once they’re dead, stay dead. No one’s at home

in Ancient Rome,

that took grand Greece with it. And how divine a

pattern for China?

First of all, it’s just flat-out witty and clever, and he keeps it up for eight

stanzas. Then there is the occasional and marvelous internal, feminine rhyme,

which makes it even funnier. If you simply glance at the poem on the page, you

don’t notice the rhyme, but when you read it aloud, it’s a howler. You have to

laugh. Cole Porter couldn’t have done it any better.

And yet by the last two stanzas he’s talking about something quite serious—the

allegation that he, like John Cheever, was an unwanted child, a “failed

abortion.” There is a stark seriousness behind the virtuoso clowning.

MB: Where do you think such talent originates?

JC: I don’t know. It beats me. He can be terribly serious, when he wants to, but

always with an edge. Some of his quatrains are as good as Landor’s. Consider:

Yet Another Apology

Why's he so cutting, ironic, unkind,

like those bitter old pagans of Greece?

"A positive mind is a turbulent mind."

My negative mind is at peace.

And also:

My tongue is rough, you find. My tongue replies:

The truth is, though unkind, kinder than lies.

MB: You mentioned Walter Savage Landor, who had one of the best middle names in

poetry. Didn’t you connect Moore with Landor in a commemorative way, shortly

after the former’s death?

JC: Well, yes. At The HyperTexts you

were asking for comments to add to that wonderful “Tribute and Memorial” page

you put up in Moore’s memory. I’ll tell you the truth, and show my ignorance at

the same time. I had barely heard of Richard Moore at that point, and I never

had the privilege of meeting him or corresponding with him, as you did.

But we fall in love with the work first, and the poet later, if at all.

Everybody loves Larkin’s poems, but nobody loves Larkin. Richard Moore, in

contrast, seems to have been a sweet man and also a fine poet.

When I wrote my little tribute to him, I had already a fan of the poems, and I

was further charmed by your online photos showing him with that twinkle in his

eye and that long, gray, Ancient Mariner’s beard. One of Landor’s commemorative

quatrains I revere is the one about his first seeing a lock of “Lucretia

Borgia’s Hair” in some museum in Florence or Venice:

Borgia, thou once were almost too august

And high for adoration; now thou’rt dust;

All that remains of thee these plaits unfold,

Calm hair, meandering in pellucid gold.

I tried to imagine what it might be like, years hence, to be in some obscure New

England historical museum and come upon a lock of Richard Moore’s beard. A relic

of the true Moore. I thought that paying homage to both poets might please

Richard’s ghost, and came up with this:

On Seeing a Lock of Richard Moore’s Beard

Richard, thou once wert almost indestruct-

Ible and bushy bearded;—now thou‘rt plucked!

All that remains of thee these plaits infold –

Able to tickle still, and never to grow old!

MB: You even stayed with approximately the same rhymes. A nice tribute! I was

pleased by the kinds of responses and tributes that Richard and his work

received.

JC: All greatly deserved, every one of them. Of course he left us that

impressive long poem, the mouse epic, but his shorter riffs are wonderful, and

as good as anything W. S. Gilbert or Tom Lehrer ever wrote. I think, too, he

would have been marvelous at writing lyrics for popular songs. It’s a pity he

never teamed up with a Johnny Mercer or a Hoagy Carmichael.

What magnificent rhyming throughout his work! He just keeps tossing them off! In the admirably entitled “Poem about

Vietnam that Didn’t Suit Anyone at the Time,” nominally addressed to Lyndon

Johnson, he’s rhyming abab, and about half of the b rhymes are feminine:

and now the boot is falling off;

I think the white and naked toes grow fungal;

I do not think our minds will ever doff

what they put on in Asia’s jungle.

In the next stanza he seems to stand Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel” on its head, continuing to satirize one war while

poking fun at another poet’s horror stemming from still another war:

I hear a mother’s anxious tears

who supplicates her decorated hero

to throw away that nasty bag of ears

that she found, cleaning out his bureau.

Out of fairness to Ms. Forché, I’m not sure about the timing. Moore’s poem may

have come a decade before hers. It’s something for the scholars to sort out.

MB: Do you think the scholars are going to cabbage onto Moore’s work, now that

he’s gone?

JC: Well, I know Claudia Gary is doing a splendid job of tending the flame—of

gathering up and preserving the evidence. Let’s hope something good comes from

her endeavors. After all, he did publish a number of worthy books during his

lifetime. But this is the digital age. The HyperTexts, The New Formalist, and other sites

have done him a considerable service by making his work available online.

MB: Where would you place him and his work in the pantheon of recent formalist

poets?

JC: Obviously he rates very high. He considered himself both a formalist and a

classicist, and while that’s largely true, it really doesn’t matter. He was

simply a good poet. I think his argument for formal poetry was by example rather

than by precept. And that’s a good thing. The entire discussion about free verse

versus traditional forms seems almost superannuated now—as Quincy Lehr

suggested not long ago in the pages of

Raintown Review. It’s been

amply discussed, and now it’s time to move on.

MB: Move on to what?

JC: Maybe “get back to” is a better phrase. Get back to writing quality poems.

Get back to producing honest criticism. What matters most of all is excellence.

It takes genuine, sincere, serious poets to achieve it, and honest, dedicated,

unflappable literary critics to identify it. Such individuals presently seem to

be in short supply.

MB: A tall order, but one that appeals to me as a poet, editor and reader.

Before we leave Richard Moore, what do you think his place will be in

twentieth-century American poetry?

JC: I think—and my appraisal would no doubt please him inordinately—that in

the post-war period he was the Bettie Page of American poetry.

MB: The WHAT?

JC: Just what I said. They’re near contemporaries, too. Her dates are 1923-2008

and his are 1927-2009. And when you stop and think about it, their achievements

are stylistically parallel if not exactly similar in terms of content. She’s

dazzlingly photogenic, he’s dazzlingly poetic. And both were originally closely guarded secrets, out of the mainstream.

Here’s this pin-up queen that all the boomers were secretly getting off on from

about 1950 to 1970, but never publicly acknowledging or telling their wives or

girl friends about. And here’s this largely formal poet the other top poets

thought was first-rate but still kept mostly to themselves

MB: Are you pulling my leg?

JC: No, seriously, think about it. What’s so impressive about the classic Bettie

Page archival photos, even now? It’s not the alleged pornography. Bettie's stuff

was relatively tame, even back then. Norman Rockwell would have approved. There was no explicit sex and only harmless nudity. And of course it’s strictly Hallmark Greeting Cards today, compared to

what’s available on the web.

No, the great thing about Bettie Page was that it was all a put-on. Bettie was

in on the joke, and was obviously having a great deal of fun putting it across.

You can see it in the way her eyes sparkled. She

and Bunny Yeager were having the time of their lives, pimping all those horny

boomers out there. And as far as I know,

there was no hint of her being exploited, as Linda Lovelace would be, a couple

of decades later.

Here the non-believer or the skeptic is going to say, that’s just the problem,

it was all a put-on, it was play-acting, it wasn’t serious. Not respectable

photography at all. And it was so-o-o tacky. I disagree.

It was out of that great tradition of

black-and-white stag films, back in the 1940s. Sure, it was make-believe. All

acting is make-believe. So is all pornography. So is all poetry, for that

matter. But she did a great job of projecting her unique image, and today her

subsidiary rights earnings approach those of Marilyn and Elvis. She must have

been doing something right.

I mean, when they were shooting in Boca Raton in 1954, Yeager posed her

in a leopardskin leotard next to two live

cheetahs. That wasn’t pornography, it was early, innovative post-modernism.

Eat your heart out, Cindy Sherman. Page was no ingénue. She and her

photographers knew exactly what they were doing: having a ball!

In the photos you’ve posted online, you can see the same kind of glee in Richard

Moore’s eyes. It’s in the poems, too. He’s having immense fun with all that

rhyme and all those learned allusions. Like Bettie Page, he’s a cutie-pie, an

exhibitionist, standing on his head and laughing not at us but with us.

He’s said, over and over, in his best essays, that the real reward of poetry is

simply the writing of it. And he’s right. The reward for Bettie Page was the

essentially the same—romping around in her underwear in front of the camera,

knowing that half of America was watching, and finding the experience vastly

amusing.

She made a living at it for a while but she never got rich. For Page, the fame

and the adulation, such as it was, didn’t come until much later, long after she

got religion, and only after she was old and understandably camera-shy.

But she never expected to become an icon, and when it happened, it seems to have

been a great shock to her. Still, there’s an unmistakable joy in those photos,

and that’s her legacy. And there’s an unmistakable joy in Richard Moore’s verse,

too.

Moore never achieved her level of notoriety or iconic stature, but most of that

has been posthumous for Page anyway. That old dog Richard Moore may yet have his

day.

MB: Whew! I’ll refrain from asking you who was Milton’s dark aesthetic twin in

the seventeenth century.

JC: Probably a good idea. Although

I’m sure he had one. What are Madame de Sade’s dates? She was a century later,

unfortunately.

MB: Do you have a psychic twin among contemporary artists?

JC: That’s not for me to say. But

if I had the privilege of choosing, I would hope it would be Vivian Maier.

MB: Jared, I wish we had time to pursue that train of thought, but we’re nearing

the end of the interview, and I still want to ask if you have anything to say

about the difference between formal poetry and free verse.

JC: I think many good things have already been pointed out about that

difference, so much so that there’s almost nothing I could add. There’s a world

of wisdom contained in Frost’s brief admonition that we should write about

“griefs, not grievances.” I would

simply say, then, when it comes to free verse versus formal, “poems, not

poetry.”

MB: Care to explain?

JC: No, but in closing, I’ll give you an illustration. It’s one that’s come to

me lately as I’ve listened to the free-versus-formal discussion. It started me thinking about something we all know and love, the game of basketball.

MB: Great! That’s something I know a little about. I was a pretty good hoopster

in my day, but after reaching six feet at age thirteen, I stopped growing at

six-two, and didn't have the ball-handling skills to play guard in college.

JC: My basketball career was hauntingly similar. The road to couch potatoism is

paved with former high-school basketball stars who couldn’t cut it in college.

But we all still love the game, right? And that got me to thinking recently

about the parallels between basketball and poetry.

MB: I can only hope that Phil Jackson is listening in!

JC: I should make it clear that I take no sides, hold no brief for formal poetry

or free verse. I write both and would much prefer to let my work speak for me.

And good luck to those who take different sides in the discussion.

Instead, in what I am about to say here, at the end of this interview—and

thanks so much, dear Michael, for the hospitality, and for putting up with me

for this long—what I am about to say, then, is that if the sneaker fits, wear

it.

Ahem. Yes, basketball, that curious game in which the basic task is childishly

simple: put the ball in the basket. Everything else is secondary, and yet if the

ball does not go in, there is no basket made, and no basketball. Transport

yourself now to the typical basketball game you have witnessed dozens or

hundreds of times in the past. There are basically two parts to each public

session—the shootaround and the actual game.

The much briefer shootaround constitutes the pre-game ritual for NBA teams,

college and high-school teams, and other teams at all levels, male and female.

It is formless and has no rules or prescriptions. During the shootaround, twelve

or fifteen individual players on each side, with an equal number of balls, keep

shooting repeatedly for their respective baskets.

Most shots go in but some don’t; it really doesn’t matter.

For a while, each player chases after

his own rebounds, though sometimes ball boys help retrieve them. Sometimes the

players form two lines and make layups, grab rebounds, and feed each other the

ball, but in the NBA they can’t dunk, so it’s all sort of laid-back and

automatic. But colorful, since they’re still wearing their warm-ups.

Suddenly the horn blows, the refs come out, the ball is thrown up, and the game

begins. Instantly it becomes something quite different from the shootaround. The

game of basketball is conducted according to a myriad of arcane rules, odd

conditions, weird procedures, strange requirements, penalties, rewards,

time-outs, whistles blowing, hand signals, and other peculiarities that are

either forbidden, out-of-bounds, poorly coached, or properly booed.

We took in all this arcana, of course, with our mother’s milk, so we no longer

consider how utterly strange it is. As a matter of fact, we are a nation of

presumed experts on the technicalities and finer points of basketball.

Everything about it seems perfectly natural to us, both the shootaround and the

actual game.

But as I say farewell, and thanks again, Mike, I would invite you—and also

you, Dear Reader, out there in cyberspace—to ask yourself three questions.

First, if there are paying customers, or even fans who got in free, what have

they actually come to see—the shootaround or the game?

Second, which do you think is harder to do—participate in a shootaround, or

play in the NBA?

Third, which of these two accomplishments do you admire more?

MB: Jared, in my role as official timekeeper, I’m going to declare that you just

hit the winning trey that keeps us from going into overtime!

The HyperTexts