The HyperTexts

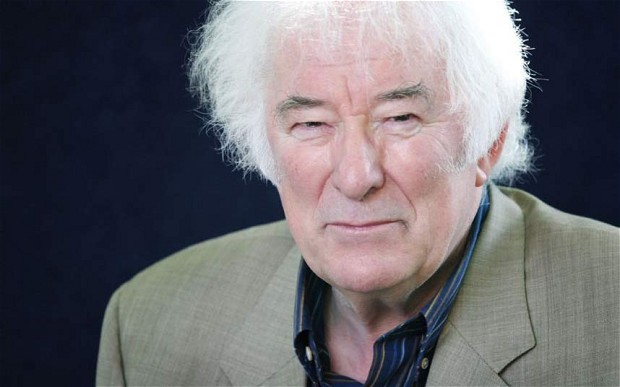

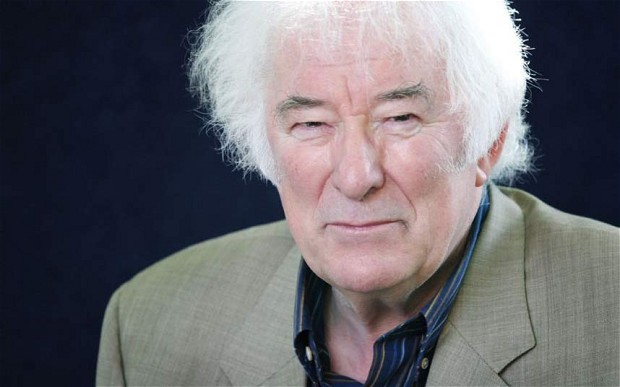

Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013), whom Robert Lowell and others have called the most

important Irish poet since William Butler Yeats, died on Friday, August 30,

2013 in Dublin. Irish prime minister Enda Kenny said the poet's death had

brought "great sorrow to Ireland, to language and to literature." Heaney was the

recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature for what the Nobel committee

deemed to be "works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday

miracles and the living past." In its obituary The Independent described Heaney as "probably the best-known

poet in the world" and the "greatest living poet" at the time of his death. And yet for all his popularity and star power, Heaney was

the poet of peat bogs and the grubby, grimy things they preserve. (His best-known

poems include "Bogland," "The Tollund Man," "Bog Oak,"

"Punishment," and "Digging." Even his birthplace sounds "peaty," as he was born

in Mossbawn, a remote corner of Northern Ireland, symbolically placed "between

the marks of English influence and the lure of the native experience, between

the 'demesne' and the 'bog.'" The oldest child of a farmer and cattle dealer,

Heaney grew up surrounded by family and friends "immersed in the rituals of

rural Catholic life." In his highly original poetry he sought to find "images

and symbols adequate to our predicament." And he spoke warmly about writing

poetry as a master carpenter might speak fondly about building: of "summoning

the energies of words," of "the actual pleasure of feeling something under your

hand and growing" and of poems "full of voices, full of people." But he also mentioned

his art helping him cope with the fear of a terrible silence that seems

to have always haunted him. Heaney, an Ulsterman, was known for his poems about the

"Troubles" of Northern Ireland, which were written in an earthy-but-lyrical

Irish/English patois. And while England may have conquered and occupied Ireland, it

seems Heaney may have returned the favor: when he turned 70 in 2009 it was

announced that two-thirds of the poetry collections sold in the UK the previous

year were his.

Punishment

by Seamus Heaney

I can feel the tug

of the halter at the nape

of her neck, the wind

on her naked front.

It blows her nipples

to amber beads,

it shakes the frail rigging

of her ribs.

I can see her drowned

body in the bog,

the weighing stone,

the floating rods and boughs.

Under which at first

she was a barked sapling

that is dug up

oak-bone, brain-firkin:

her shaved head

like a stubble of black corn,

her blindfold a soiled bandage,

her noose a ring

to store

the memories of love.

Little adulteress,

before they punished you

you were flaxen-haired,

undernourished, and your

tar-black face was beautiful.

My poor scapegoat,

I almost love you

but would have cast, I know,

the stones of silence.

I am the artful voyeur

of your brain’s exposed

and darkened combs,

your muscles’ webbing

and all your numbered bones:

I who have stood dumb

when your betraying sisters,

cauled in tar,

wept by the railings,

who would connive

in civilized outrage

yet understand the exact

and tribal, intimate revenge.

(There is an Arabic translation of "Punishment" by the Palestinian poet Iqbal

Tamimi, at the bottom of this page.)

The Forge

by Seamus Heaney

All I know is a door into the dark.

Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting;

Inside, the hammered anvil’s short-pitched ring,

The unpredictable fantail of sparks

Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water.

The anvil must be somewhere in the centre,

Horned as a unicorn, at one end and square,

Set there immoveable: an altar

Where he expends himself in shape and music.

Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose,

He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter

Of hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows;

Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick

To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

Personal Helicon

by Seamus Heaney

for Michael Longley

As a child, they could not keep me from wells

And old pumps with buckets and windlasses.

I loved the dark drop, the trapped sky, the smells

Of waterweed, fungus and dank moss.

One, in a brickyard, with a rotted board top.

I savoured the rich crash when a bucket

Plummeted down at the end of a rope.

So deep you saw no reflection in it.

A shallow one under a dry stone ditch

Fructified like any aquarium.

When you dragged out long roots from the soft mulch

A white face hovered over the bottom.

Others had echoes, gave back your own call

With a clean new music in it. And one

Was scaresome, for there, out of ferns and tall

Foxgloves, a rat slapped across my reflection.

Now, to pry into roots, to finger slime,

To stare, big-eyed Narcissus, into some spring

Is beneath all adult dignity. I rhyme

To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.

Night Drive

by Seamus Heaney

The smells of ordinariness

Were new on the night drive through France;

Rain and hay and woods on the air

Made warm draughts in the open car.

Signposts whitened relentlessly.

Montrueil, Abbéville, Beauvais

Were promised, promised, came and went,

Each place granting its name’s fulfilment.

A combine groaning its way late

Bled seeds across its work-light.

A forest fire smouldered out.

One by one small cafés shut.

I thought of you continuously

A thousand miles south where Italy

Laid its loin to France on the darkened sphere.

Your ordinariness was renewed there.

A Kite for Aibhín

by Seamus Heaney

after "L'Aquilone" by Giovanni Pascoli (1855-1912)

Air from another life and time and place,

Pale blue heavenly air is supporting

A white wing beating high against the breeze,

And yes, it is a kite! As when one afternoon

All of us there trooped out

Among the briar hedges and stripped thorn,

I take my stand again, halt opposite

Anahorish Hill to scan the blue,

Back in that field to launch our long-tailed comet.

And now it hovers, tugs, veers, dives askew,

Lifts itself, goes with the wind until

It rises to loud cheers from us below.

Rises, and my hand is like a spindle

Unspooling, the kite a thin-stemmed flower

Climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher

The longing in the breast and planted feet

And gazing face and heart of the kite flier

Until string breaks and—separate, elate—

The kite takes off, itself alone, a windfall.

In Memoriam M.K.H., 1911-1984

by Seamus Heaney

She taught me what her uncle once taught her:

How easily the biggest coal block split

If you got the grain and the hammer angled right.

The sound of that relaxed alluring blow

Its co-opted and obliterated echo,

Taught me to hit, taught me to loosen,

Taught me between the hammer and the block

To face the music. Teach me now to listen,

To strike it rich behind the linear black.

A cobble thrown a hundred years ago

Keeps coming at me, the first stone

Aimed at a great-grandmother's turncoat brow.

The pony jerks and the riot's on.

She's couched low in the trap

Running the gauntlet that first Sunday

Down the brae to Mass at a panicked gallop.

He whips on through the town to cries of 'Lundy!'

Call her 'The Convert.' 'The Exogamous Bride.'

Anyhow, it is a genre piece

Inherited on my mother's side

And mine to dispose with now she's gone.

Instead of silver and Victorian lace

the exonerating, exonerated stone.

Polished linoleum shone there. Brass taps shone.

The china cups were very white and big—

An unchipped set with sugar bowl and jug.

The kettle whistled. Sandwich and tea scone

Were present and correct. In case it run,

The butter must be kept out of the sun.

And don't be dropping crumbs. Don't tilt your chair.

Don't reach. Don't point. Don't make noise when you stir.

It is Number 5, New Row, Land of the Dead,

Where grandfather is rising from his place

With spectacles pushed back on a clean bald head

To welcome a bewildered homing daughter

Before she even knocks. 'What's this? What's this?'

And they sit down in the shining room together.

When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of clean water.

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other's work would bring us to our senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives—

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

Fear of affectation made her affect

Inadequacy whenever it came to

Pronouncing words 'beyond her'. Bertold Brek.

She'd manage something hampered and askew

Every time, as if she might betray

The hampered and inadequate by too

Well-adjusted a vocabulary.

With more challenge than pride, she'd tell me, 'You

Know all them things.' So I governed my tongue

In front of her, a genuinely well-

Adjusted adequate betrayal

Of what I knew better. I'd naw and aye

And decently relapse into the wrong

Grammar which kept us allied and at bay.

The cool that came off sheets just off the line

Made me think the damp must still be in them

But when I took my corners of the linen

And pulled against her, first straight down the hem

And then diagonally, then flapped and shook

The fabric like a sail in a cross-wind,

They'd make a dried-out undulating thwack.

So we'd stretch and fold and end up hand to hand

For a split second as if nothing had happened

For nothing had that had not always happened

Beforehand, day by day, just touch and go,

Coming close again by holding back

In moves where I was x and she was o

Inscribed in sheets she'd sewn from ripped-out flour sacks.

In the first flush of the Easter holidays

The ceremonies during Holy Week

Were highpoints of our Sons and Lovers phase.

The midnight fire. The paschal candlestick.

Elbow to elbow, glad to be kneeling next

To each other up there near the front

Of the packed church, we would follow the text

And rubrics for the blessing of the font.

As the hind longs for the streams, so my soul . . .

Dippings. Towellings. The water breathed on.

The water mixed with chrism and oil.

Cruet tinkle. Formal incensation

And the psalmist's outcry taken up with pride:

Day and night my tears have been my bread.

In the last minutes he said more to her

Almost than in their whole life together.

'You'll be in New Row on Monday night

And I'll come up for you and you'll be glad

When I walk in the door . . . Isn't that right?'

His head was bent down to her propped-up head.

She could not hear but we were overjoyed.

He called her good and girl. Then she was dead,

The searching for a pulsebeat was abandoned

And we all knew one thing by being there.

The space we stood around had been emptied

Into us to keep, it penetrated

Clearances that suddenly stood open.

High cries were felled and a pure change happened.

I thought of walking round and round a space

Utterly empty, utterly a source

Where the decked chestnut tree had lost its place

In our front hedge above the wallflowers.

The white chips jumped and jumped and skited high.

I heard the hatchet's differentiated

Accurate cut, the crack, the sigh

And collapse of what luxuriated

Through the shocked tips and wreckage of it all.

Deep-planted and long gone, my coeval

Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole,

Its heft and hush became a bright nowhere,

A soul ramifying and forever

Silent, beyond silence listened for.

Arabic translation of Seamus Heaney's poem "Punishment" by the Palestinian poet

Iqbal Tamimi:

وفاة الشاعر الإيرلندي "شيموس هيني" الذي مجّد وحل المستنقعات

إقبال التميمي

توفي يوم أمس الجمعة 30 من أغسطس 2013 في مدينة دبلن، الشاعر الايرلندي

شيموس هيني المولود عام 1039. قال عنه روبرت لويل بأنه أشهر شاعر ايرلندي منذ

الشاعر ويليام بتلر ييتس.

قال رئيس الوزراء الايرلندي "اندا كيني" أن وفاة الشاعر هيني جلبت "الحزن الكبير

لأيرلندا، وإلى اللغة وإلى الأدب".

كان هيني قد فاز بجائزة نوبل للآداب عام

1995 لأنه وحسب ما قالت عنه لجنة تقييم الأعمال الأدبية لجائزة نوبل "أعماله ذات

جمال غنائي وعمق أخلاقي. وأشاد شعره بالمعجزات اليومية والماضي الذي ما زلنا

نحياه".

في تأبينه وصفت صحيفة الاندبندنت البريطانية هيني على أنه "ربما أكثر الشعراء شهرة

في العالم". ورغم شعبيته ونجوميته، كان هيني شاعر المستنقعات والوحل والأشياء

الوضيعة والمتسخة التي حملت رمزية القمع السياسي والاجتماعي. من أشهر قصائدة

"أرض المستنقعات"، "رجل تولوند"، " البلوط المستنقع"، "عقاب"، "الحفر"، "المصهر"،

"موت صاحب مذهب الطبيعة"، "قطاف التوت الأسود". إضافة إلى ترجمته الشهيرة للملحمة

الأنجلو- ساكسونية "بيوولف" من اللغة الانجليزية القديمة والمكونة من 3182 بيت

طويل.

معروف أن هيني من أهالي قطاع ألستر في

أقصى شمال ايرلندا لذلك اشتهر بكتاباته الشعرية السياسية عن الاضطرابات التي حصلت

في ايرلندا الشمالية. قصائده كانت فظة نوعا ما غنائية وبلهجة ايرلندية-انجليزية

عامية. ورغم أن بريطانيا احتلت وطنه ايرلندا وكتب الكثير عن قهرها، إلا أنه في عيد

ميلاده السبعين الذي صادف عام 2009 كشف عن أن ثلثي المجموعات الشعرية التي بيعت في

المملكة المتحدة في العام السابق كانت من انتاجه.

سأقدم هنا في ذيل المادة ترجمة لنموذج من شعره. قصيدة بعنوان "العقاب" وفيها يتحدث

عن العنف ويستخدم أسلوب المقارنة في سلسلة من قصائده المشابهه عن اكتشاف الحفريات

الأثرية في المستنقعات شمال ايرلندا وشمال أوروبا. حيث تم استخراج رفات بقايا بشرية

من ضحايا العنف والقرابين البشرية مستخدما من خلال أشعاره استعارات مناسبة وموازية

لطرح موضوع السياسات الطائفية في الحياة العصرية في ايرلندا الشمالية. واستخدام

الاستعارات للتحدث عن النسبة العالية من العنف من خلال الإعدامات القاسية وتعذيب

أهالي تلك المستنقعات في الماضي كمثل يوازي الفظائع التي حصلت في ايرلندا في

السبعينيات. وقصيدة "العقاب" الشهيرة هي إحدى سلسلة قصائد كتبها واستخدم فيها صورة

المرأة كضحية قدمت قربانا لأنها زانية. نجد في القصيدة سخرية مؤلمة ونبرة تعاطف مع

الضحية إذ يقول "أكاد أحبك".

في القصيدة شيء من المقارنة بين المرأة التي أعدمت ووجدت غارقة في الوحل وبين

النساء الإيرلنديات اللواتي خنّ ايرلندا في السنوات الأخيرة إذ تواطئن مع المعتدي

وتمت معاقبتهن بتلطيخ وجوههن بالقطران. مرة أخرى، إنجلترا هي القوة القمعية في

قصائده وهي التي أدت إلى وفيات لم يكن لها داع من نساء ورجال ايرلندا. لكن لوحظ في

القصيدة أن الشاعر وجد نفسه في خانة عدم القدرة على التفريق بين ما هو صحيح وما هو

خطأ إذ وقع بين الشعور "بالغضب المتحضّر" وبين تفهم أسباب "الأخذ بالثأر بأسلوب

قبلي همجي متخلف" كما كانت تتم معاقبة النساء الزانيات في العصر الحديدي.

جمالية القصيدة أو تقدير الأدباء لها كانت نتيجة استخدامه أسلوب الرمز والتشبيه

لتفادي الحديث مباشرة عن النزاعات الطائفية أو ذكر أسماء معروفة لأشخاص اقترفوا

الفظائع في ايرلندا الشمالية واستخدام الشعر ليساعد القراء في الإطلال على مشاعرهم

الداخلية ومراجعة أنفسهم بعمق.

العقاب

شعر سيموس هيني – ترجمة الشاعرة الفلسطينية إقبال التميمي

أستطيع أن أشعر بسحب

الرسن خلف

عنقها، والريح

على مقدمة جسدها العاري.

تضرب حلمتيها

كخرز من العنبر،

تهز ملابسها الخفيفة

على أضلاعها.

أستطيع ان أرى إغراقها

جسد في المستنقع،ال

والحجر الثقيل،

والقضبان والأغصان العائمة.

وما تحتها. في البداية

كانت مثل شتلة تنبح

تم نبشها

عظام من البلوط، وربع برميل دماغ:

رأسها المحلوق

مثل شعيرات ذرة سوداء

معصوبة العينين برباط وسخ

حبل مشنقتها على شكل حلقة

احفظي

ذكريات الحب

أيتها الزانية الصغيرة

قبل أن يعاقبوكي

كنت شقراء الشعر

ضعيفة التغذية، ووجهك المسود بفعل القطران

كان جميلاً.

يا مسكينتي يا كبش الفداء

أكاد أحبك

ولكن من شأني أن،

أنا أعرف،

بأنني سارجمك بحجارة الصمت

أنا الداهية المتلصص

على دماغك المكشوف

وأمشاطك المغروزة

ولسع عضلاتك بالسياط

وجميع عظامك المرقمّة:

أنا الذي وقفت أبكماً

عندما قامت أخواتك الخائنات

الملوثات بالقطران

بالبكاء على السور

من من شأنه التواطؤ

في غضب متحضر

ومع ذلك، يفهم تماما

الثأر القبلي الحميم

The HyperTexts