The HyperTexts

Shakespeare's Sonnets: Analysis, Speculations, Intuition and Deduction

Who was the Fair Youth? the Dark Lady? the Rival Poet? the Author of the

Sonnets?

The Fair Youth: Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton; William Herbert,

third Earl of Pembroke

The Dark Lady: Elizabeth Wriothesley, third Countess of Southampton (Henry's

wife); Henry himself; Emelia Lanier (a female poet); Mary Fitton; Lucy Negro;

Queen Elizabeth

The Author: William Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon, Francis Bacon, Edward de

Vere

The Rival Poet: Geoffrey Chaucer, Christopher Marlowe, Ben

Jonson, George Chapman, Thomas Nashe, Edmund Spenser, Sir Walter Ralegh,

George Peele, Gervase Markham, Michael Drayton, Samuel Daniel,

Richard Barnfield, John Davies, Barnaby Barnes

compiled

by Michael R. Burch with information gleaned from various public websites

This page

includes Is Shakespeare Dead? by

Mark Twain and Was Edward de Vere the real Shakespeare?

Shakespeare's sonnets are 14 lines each, and I believe they were

originally divided into groups of 14 sonnets. For instance, sonnets 1-14

focus on Shakespeare's attempts (perhaps not fully sincere) to convince the Fair

Youth that he will be forgotten after death if he fails to have children. With

sonnet 15 (14+1), Shakespeare suddenly introduces the (ta-da!) new idea that his

poetry can make the Fair Youth immortal, beginning a new theme and thread.

Sonnets 127-154 comprise the Dark Lady sequence of 28 (14*2) sonnets. But

over the years various editors have taken liberties with the ordering of the

poems, so unless the original order can be restored, we may never know exactly

what Shakespeare was up to. My guess is that he planned to write 196 sonnets

(14*14), but either ran out of steam, inspiration, or time. Or will the

remaining sonnets turn up in someone's attic someday?

The Fair Youth or Fair Young Lord

Who was the Fair Youth or Fair Young Lord to whom most (perhaps all)

of the sonnets were addressed? While everyone is entitled to his/her opinion,

for me the answer seems obvious ...

Henry Wriothesley (1573-1624), the third Earl of Southampton; the portrait

above, circa 1590–93, has been attributed to John de Critz. The miniature below

is by an unknown artist.

In Sonnet 3, Shakespeare said that the Fair Youth was the image of his mother:

"Thou art thy mother's glass and she in thee / Calls back the lovely April of

her prime." Here as evidence is a picture of Mary Wriothesley, Countess of

Southampton, nee Mary Browne.

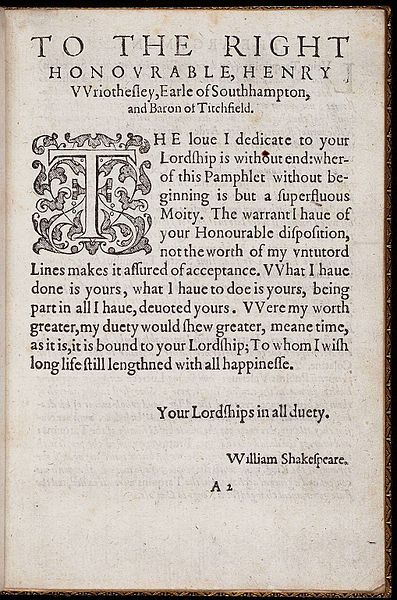

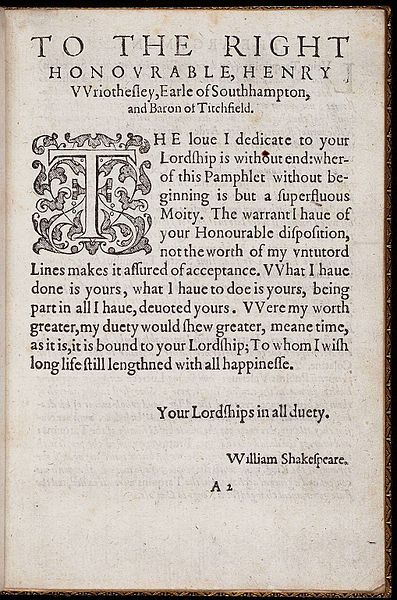

Here as further evidence is Shakespeare's rather gushy dedication of his poem

"The Rape of Lucrece" to Southampton:

Southampton fits many of the major clues to be found in Shakespeare's sonnets:

he looked like a beautiful girl (20); he was the image of his mother (3); he was

reluctant to marry (1-17); he was of high rank and social status (36-37); as a

royal ward he was a candidate for a gilded tomb (101); he had his portrait

painted to give away to friends (16, 47); Shakespeare dedicated two of his major

poems to him and he was flattered by other notable poets; he was a star

attracting other people into his orbit (1-20); etc. Also, Southampton’s motto

Ung par Tout,

Tout par Ung ("One for All, All for One") is a recurring theme in the

sonnets (8, 31, 76, 105). Furthermore, lines spoken by the goddess in Venus

and Adonis,

dedicated by Shakespeare to Southampton, have been called "virtual

carbon copies" of lines in sonnets 1-17.

Sonnet 20 suggests that the Fair Youth may have been

a hermaphrodite, since Shakespeare rather baldly says that when Nature created

the Fair Youth as a

woman, then added a penis as an afterthought, it did "nothing" for him. Sonnet XX

is, I believe, the only Shakespearean sonnet in which all the end rhymes are

feminine. Is the double kiss symbol XX perhaps intentional? And the number 20

may also be significant because it is the sum of all the digits in a couple's

hands.

20

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion:

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created;

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

Do lines 9-14 mean that by the addition of a penis to the Fair Youth, nature

gave Shakespeare nothing that he wanted, meaning that if there was sex he was

the one doing the mounting? Does the closing couplet suggest a Platonic

relationship, or is Shakespeare perhaps saying "We have the real

love, but I don't want to deny you pleasure, so you can have sex with women

too."? In any case line thirteen is very clever. And if Shakespeare's nickname

for the Fair Youth was Hugh, line seven becomes very interesting indeed. The

name Hugh in Old German can mean "heart," "mind" and "soul." The words "human"

and "humane" may branch out from this ancient root. And I have read somewhere

that the feminine form Hugh(e) could mean a servant or some sort of obedient

position ...

While there is obviously some speculation on my part above, Shakespeare's word

choices alone might be taken to suggestively add up to a dominant/submissive

relationship: "master mistress," "a man in hue," "controlling," "defeated,"

"pricked" and "love's use."

The Author of the Sonnets

Furthermore, if Edward de Vere was the "real" Shakespeare, as has been claimed,

the plot decidedly thickens, because it was de Vere's eldest daughter,

Elizabeth, whom Shakespeare was pleading with Southampton to marry in the first

seventeen sonnets (the "marriage sonnets). Also, the "Shakespearean

sonnet" form was actually invented by de Vere's uncle, Henry Howard, the fifth

earl of Surrey. And as Mark Twain pointed out in his essay "Is

Shakespeare Dead?" there is no evidence that William Shakespeare of

Stratford-on-Avon was literate, that he owned a single book, or that he ever

wrote a poem except perhaps the quaint one that adorns his headstone. When

Shakespeare died, even in his hometown his death seemed to go unnoticed. His

will, written shortly before his death, mentions the inheritance of his

second-best bed, plates and a bowl, but nothing about his poetry, plays,

library, or even a single book. In those days books were highly valuable, so

they would likely have been mentioned in the wills of people who owned them. And

how, pray tell, did a rural hayseed end up with so much in-depth

knowledge of the ways of royals and their manners, laws and courts? Twain came

to the Occam's Razor conclusion that William Shakespeare of Stratford was

disregarded in his hometown for years after his death because he was not the

author of the plays and poems that now bear his name. And how can anyone

conclude that the poem on Shakespeare's gravestone was written by the same great

skeptical philosopher who wrote the plays and sonnets?

Good friend for Iesus sake forbeare

To digg the dust encloased heare:

Blest be ye man yt spares thes stones

And curst be he yt moves my bones.

The real Shakespeare, whoever he was, claimed many times that his poems would

make him and his subjects immortal. He never mentioned relying on Jesus for

anything. I therefore agree with Mark Twain, and rest my case. While I do not

claim to "know" the identity of the real Shakespeare, I think the marriage

sonnets strongly suggest that the real Shakespeare was Edward de Vere.

The Rival Poet

Candidates: Geoffrey Chaucer, Christopher Marlowe, Ben

Jonson, George Chapman, Thomas Nashe, Edmund Spenser, Sir Walter Ralegh,

George Peele, Gervase Markham, Michael Drayton, Samuel Daniel,

Richard Barnfield, John Davies, Barnaby (Barnabe)

Barnes

After having claimed the Fair Youth to be superior to women in Sonnet 20, in the

very next sonnet Shakespeare introduces a new character, commonly called the

Rival Poet, and begins to make the case that he is the superior poet. Here again

the number of the sonnet may be significant, since three and seven are "holy" or

"perfect" numbers, and 21 is their product (3*7). Is Shakespeare perhaps

suggesting by the number chosen that his rival is considered to be the height of

poetic perfection? Sonnet 21 describes a rival poet who wrote in couplets ("couplement"):

So is it not with me as with that muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse,

Who heaven it self for ornament doth use,

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse,

Making a couplement of proud compare

With sun and moon, with earth and sea's rich gems:

With April's first-born flowers and all things rare,

That heaven's air in this huge rondure hems.

While other poets have been suggested as Shakespeare's main rival, I think

Geoffrey Chaucer is the most obvious candidate, at least in this sonnet, because

he pioneered the English heroic couplet and his most famous poem, "Canterbury

Tales," begins with couplets about April's first-born flowers:

Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote

When April with his sweet showers

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

Has pierced the drought of March to the root,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

And bathed every vine in liquor

Of which vertu engendred is the flour ...

Of such virtue that flowers are engendered ...

Also, in Shakespeare's sonnets a "painted beauty" is a woman and Chaucer's first

major work was "The Book of the Duchess," an elegy for the first wife of his

patron John of Gaunt.

Furthermore, "Canterbury Tales" begins with descriptions of nature—the

sun, the moon (months), things of the earth (vines, flowers, etc.)—in a poem

about a pilgrimage, which of course concerns heavenly things. Shakespeare's

"Heaven's air" surely has multiple meanings: the life-bringing Zephyr mentioned

by Chaucer, the physical sky, the abstract heavens, and the poem itself (since

poems and songs are called "airs" and they are inspired by gods, the Muses).

Shakespeare was a master of wordplay for both humorous and serious purposes, and

I don't think there is anything accidental about "heaven's air" here.

Shakespeare's "huge rondure" also seems to apply to Chaucer and his worldview;

at his time the orthodox belief was that the earth was the stationary center of

the universe, with the sun, moon and stars forming a sort of globe above it. I

believe that in these eight lines Shakespeare was pointing out major differences

between himself and Chaucer: (1) Chaucer wrote for a woman who was artificial

and painted her face, Shakespeare for the more natural beauty and virtue of the

Fair Youth; (2) Chaucer was a true believer who sought to reconcile (couple)

nature with heaven, Shakespeare a skeptic; (3) Chaucer wrote rather mundane

nature poetry, Shakespeare had bigger things on his mind.

Chaucer has been generally considered to be the first great poet to write in the

English language, and he was the first poet to be buried at Westminster Abbey,

so when Shakespeare starts naming rival poets, it makes perfect sense for him to

begin with Chaucer. But Chaucer died long before Southampton was born, so it

seems that later references to rival poets who contended with Shakespeare for

his affections were probably about one or more other, then-living poets.

In sonnet 80, Shakespeare mentions a competitor whom he calls a "better spirit,"

who uses Southampton's name. Shakespeare claims, perhaps facetiously, that his

"saucy bark" is "inferior far" to his rival's. Poets who mentioned Southampton

in their poems and/or dedicated poems to him include George Chapman, Thomas

Nashe, George Peele, Gervase Markham and Barnaby Barnes.

In sonnet 83, Shakespeare mentions "both your poets," so in this sequence it

seems he is discussing himself and a single rival.

Sonnet 86 may give us the best clues about this rival poet's identity. As Eric

Sams points out:

One phrase in Sonnet 86 echoes [Barnaby] Barnes, namely "when your countenance

filled up his line." Barnes's sonnet to Southampton includes the actual words

"your countenance." Thus Southampton's favour is solicited for the love-lyrics

of Parthenophil and Parthenophe, so "that with your

countenance graced they may withstand" envy and criticism. The word

"countenance" has indeed "filled up" Barnes's line—to overflowing, since it adds

an extra syllable. This congruence between the two sources suggests that

Shakespeare's thirteenth line (which scans "countenance" correctly) means what

it says. On that basis, which poet had been taught by spirits to write above a

mortal pitch, received aid from his compeers by night, and was nightly gulled

with intelligence by an affable familiar ghost? Those words are regularly

tortured into confessing some connection with Marlowe or Chapman. But Marlowe

died in 1593; and there is no record that Chapman's innocuous claim to have

conversed with the spirit of Homer was made before 1609. Besides, their two

candidatures cancel each other out. Above all, neither of them can be shown to

have sought Southampton's favour at a time when he was Shakespeare's well-known

patron. But Barnaby Barnes did, with a sonnet which has a line filled with

Southampton's countenance, and in 1593, when Venus and Adonis was first

published. Barnes, furthermore, was a notorious occultist. His intimate friend

William Percy asks him, by name, in his own Sonnets to Coelia

(1594): "What tell'st thou me, by spells thou hast won thy dear?" John Ford, who

also knew Barnes well, writes in The Lover's Melancholy: "If it be not

Parthenophil … 't is a spirit in his likeness," while the villain Orgillus in

Ford's The Broken Heart is asked: "You have a spirit, sir, have ye? a

familiar ⁄ That posts i' the air for your intelligence?" which looks very like

an allusion to Sonnet 86. Barnes himself had already made comparable claims, in

1593. His envoi to Parthenophil and Parthenophe says that

having burned frankincense on an altar and kindled a fire of cypress-wood he

called on threefold Hecate, invocated the Furies, and dispatched a black goat to

bring Parthenope (Greek for virgin) naked to his side. Then he made a libation

of wine to the Furies, burnt brimstone, and cut rosemary with a brazen axe, to

make magic boughs. All these rituals were observed at night. This diabolism

should surely be taken seriously. In 1598 Barnes was rightly arraigned as a

poisoner before the court of Star Chamber; he escaped justice only by flight.

His later play The Devil's Charter, about a poisoner, dramatises the

conjuration of spirits, from sources including the Heptameron of Petrus

de Abano. This grimoire gives instructions about the appropriate robes, incense,

incantations, magic diagrams, goatskin parchment, and other paraphernalia to be

used in raising the apparitions that rule the hours and the seasons. They will

then fulfil one's wishes and answer one's questions, as in Sonnet 86.

The Dark Lady

Candidates: Elizabeth Wriothesley, third Countess of Southampton (Henry's wife);

Henry himself; Emelia Lanier (a female poet); Mary Fitton; Lucy Negro; Queen

Elizabeth

Was the Dark Lady perhaps also Southampton? After all, Shakespeare himself said

in his Dedication that there was "onlie one begetter" of the sonnets. Sonnet 126

(9*14) is the last one addressed by Shakespeare to the "lovely boy." Sonnet 127

(9*14+1) begins what are commonly known as the Dark Lady sonnets. But was

Shakespeare still addressing his lovely mistress-master? Was he now

exploring his lover's darker side, which for Shakespeare seemed to be the

feminine? In Sonnet 31, Shakespeare tells us not to take his mistress's darkness

literally: "In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds, / And thence this

slander as I think proceeds." Another possibility is that Shakespeare is

addressing Henry's wife: Elizabeth Wriothesley, the third Countess of

Southampton. She would have been an obvious rival for Southampton's time,

attention and affections. Or perhaps Shakespeare is addressing some other woman

they both knew. In sonnet 132, the blackness being discussed sounds like widows'

weeds, a mourning for the death of love. But sonnet 135, a riddle, seems to hint

that the Dark Lady may lie within Shakespeare himself: "Think all but one, and

me in that one 'Will.'" But it is sonnet 144 (is the number again significant?)

which most strongly suggests that the Dark Lady may be man's feminine side, at

war with his masculine "angel," as the Fair Youth and Dark Lady converge:

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still,

The better angel is a man right fair:

The worser spirit a woman coloured ill.

To win me soon to hell my female evil,

Tempteth my better angel from my side,

And would corrupt my saint to be a devil:

Wooing his purity with her foul pride.

But in sonnet 148 it seems that Shakespeare's displeasure is with Love itself:

"O cunning love, with tears thou keep'st me blind, / Lest eyes well-seeing thy

foul faults should find."

So perhaps the Dark Lady is Love or some sort of psychological hybrid. Did

Shakespeare look within and admit that the war for happiness that he waged

through his own "will" was being fought against the Dark Lady inside? Did his

masculine (rational) self decide that his feminine (emotional) self, abetted by

Love (Venus/Cupid), had undermined and betrayed him?

Commentary on the Sonnets

1

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak'st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

Sonnets 1 through 14 constantly repeat the idea that The Fair Young Lord (TFYL) risks

complete annihilation if he dies without children. For instance:

3

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest,

Now is the time that face should form another,

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother ...

But if thou live remembered not to be, [i.e., But if it is your intention not to

be remembered]

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

6

Be not self-willed for thou art much too fair,

To be death's conquest and make worms thine heir.

7

So thou, thy self out-going in thy noon:

Unlooked on diest unless thou get a son. [This is a play on words: A man who

reaches his prime without a son is like the noon sun soon to disappear from the

sky.]

Shakespeare also confirms that TFYL is as beautiful as a girl:

3

Thou art thy mother's glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime ...

Shakespeare goes on to accuse TFYL of hoarding his beauty by not sharing it with

lovers:

4

Unthrifty loveliness why dost thou spend,

Upon thy self thy beauty's legacy?

Nature's bequest gives nothing but doth lend,

And being frank she lends to those are free:

Then beauteous niggard why dost thou abuse,

The bounteous largess given thee to give?

Profitless usurer why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums yet canst not live?

For having traffic with thy self alone,

Thou of thy self thy sweet self dost deceive,

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave?

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which used lives th' executor to be.

But it seem TFYL dislikes or despises marriage. Is it, perhaps, because he's

gay?

8

Music to hear, why hear'st thou music sadly? ...

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear ... [Shakespeare seems to be

punning on single "parts" that should be used to "bear" children.]

Time and time again, Shakespeare implores TFYL to have children:

12

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night,

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silvered o'er with white:

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd

And summer's green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard:

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake,

And die as fast as they see others grow,

And nothing 'gainst Time's scythe can make defence

Save breed to brave him, when he takes thee hence.

There are 14 lines in a sonnet, so I will rely on intuition which tells me to

look for a "turn" after sonnet 14. And indeed sonnet 15 does seem to take a

turn, as Shakespeare suggest a new solution to the problem of TFYL dying

unremembered without children:

15

When I consider every thing that grows

Holds in perfection but a little moment.

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment.

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and checked even by the self-same sky:

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory.

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay,

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful time debateth with decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night,

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

Has this been Shakespeare's intention all along: to write 14 poems of 14 lines,

setting the stage for his proposal to TFYL that a great poet can immortalize

him, on the great stage of life, through his poetry? In sonnet 16, Shakespeare

gives TFYL an interesting choice, perhaps relying both on the allurements of

his pen and TFYL's distaste for marriage:

16

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time?

And fortify your self in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear you living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit:

So should the lines of life that life repair

Which this (Time's pencil) or my pupil pen

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair

Can make you live your self in eyes of men.

To give away your self, keeps your self still,

And you must live drawn by your own sweet skill.

Shakespeare then seems to hedge his bets, by pointing out that TFYL can have the

best of both worlds:

17

But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice in it, and in my rhyme.

Then, as if to prove that his powers give TFYL his best shot at immortality,

Shakespeare provides a masterful poem on the subject:

18

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed,

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course untrimmed:

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand'rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st,

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

Next, Shakespeare presents himself as the defender of TFYL against Time itself:

19

Devouring Time blunt thou the lion's paws,

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood,

Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger's jaws,

And burn the long-lived phoenix, in her blood,

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleet'st,

And do whate'er thou wilt swift-footed Time

To the wide world and all her fading sweets:

But I forbid thee one most heinous crime,

O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen,

Him in thy course untainted do allow,

For beauty's pattern to succeeding men.

Yet do thy worst old Time: despite thy wrong,

My love shall in my verse ever live young.

It is at this point that we reach sonnet 20 (XX), the "kiss kiss" poem. For the

first time we hear what sounds like homosexual love talk. Whether

Shakespeare is suggesting sex, asking for sex, or proposing something more

platonic, is almost impossible to say at this point. But my intuition and

educated guess is that Shakespeare was having sex with TFYL, and that

Shakespeare was dominant because of the lines:

... thou, the master mistress of my passion ... [Was TFYL able to master Shakespeare

by submitting to him?]

A man in hue all hues in his controlling ...

And for a woman wert thou first created;

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

21

So is it not with me as with that muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse,

Who heaven it self for ornament doth use,

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse,

Making a couplement of proud compare

With sun and moon, with earth and sea's rich gems:

With April's first-born flowers and all things rare,

That heaven's air in this huge rondure hems.

29

When in disgrace with Fortune and men's eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon my self and curse my fate,

Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man's art, and that man's scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least,

Yet in these thoughts my self almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

(Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven's gate,

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings,

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

Sonnet

127 begins the Dark Lady sonnets ...

129

Th' expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action, and till action, lust

Is perjured, murd'rous, bloody full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust,

Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight,

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had

Past reason hated as a swallowed bait,

On purpose laid to make the taker mad.

Mad in pursuit and in possession so,

Had, having, and in quest, to have extreme,

A bliss in proof and proved, a very woe,

Before a joy proposed behind a dream.

All this the world well knows yet none knows well,

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

130

My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red, than her lips red,

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun:

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head:

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight,

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know,

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet by heaven I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

131

In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds,

And thence this slander as I think proceeds.

138

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearned in the world's false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue,

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed:

But wherefore says she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O love's best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love, loves not to have years told.

Therefore I lie with her, and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

144

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still,

The better angel is a man right fair:

The worser spirit a woman coloured ill.

To win me soon to hell my female evil,

Tempteth my better angel from my side,

And would corrupt my saint to be a devil:

Wooing his purity with her foul pride ...

146

Poor soul the centre of my sinful earth,

My sinful earth these rebel powers array,

Why dost thou pine within and suffer dearth

Painting thy outward walls so costly gay?

Why so large cost having so short a lease,

Dost thou upon thy fading mansion spend?

Shall worms inheritors of this excess

Eat up thy charge? is this thy body's end?

Then soul live thou upon thy servant's loss,

And let that pine to aggravate thy store;

Buy terms divine in selling hours of dross;

Within be fed, without be rich no more,

So shall thou feed on death, that feeds on men,

And death once dead, there's no more dying then.

147

My love is as a fever longing still,

For that which longer nurseth the disease,

Feeding on that which doth preserve the ill,

Th' uncertain sickly appetite to please:

My reason the physician to my love,

Angry that his prescriptions are not kept

Hath left me, and I desperate now approve,

Desire is death, which physic did except.

Past cure I am, now reason is past care,

And frantic-mad with evermore unrest,

My thoughts and my discourse as mad men's are,

At random from the truth vainly expressed.

For I have sworn thee fair, and thought thee bright,

Who art as black as hell, as dark as night.

148

O me! what eyes hath love put in my head,

Which have no correspondence with true sight,

Or if they have, where is my judgment fled,

That censures falsely what they see aright?

If that be fair whereon my false eyes dote,

What means the world to say it is not so?

If it be not, then love doth well denote,

Love's eye is not so true as all men's: no,

How can it? O how can love's eye be true,

That is so vexed with watching and with tears?

No marvel then though I mistake my view,

The sun it self sees not, till heaven clears.

O cunning love, with tears thou keep'st me blind,

Lest eyes well-seeing thy foul faults should find.

150

Who taught thee how to make me love thee more,

The more I hear and see just cause of hate?

O though I love what others do abhor,

With others thou shouldst not abhor my state.

If thy unworthiness raised love in me,

More worthy I to be beloved of thee.

152

In loving thee thou know'st I am forsworn,

But thou art twice forsworn to me love swearing,

In act thy bed-vow broke and new faith torn,

In vowing new hate after new love bearing:

But why of two oaths' breach do I accuse thee,

When I break twenty? I am perjured most,

For all my vows are oaths but to misuse thee:

And all my honest faith in thee is lost.

154

The little Love-god lying once asleep,

Laid by his side his heart-inflaming brand,

Whilst many nymphs that vowed chaste life to keep,

Came tripping by, but in her maiden hand,

The fairest votary took up that fire,

Which many legions of true hearts had warmed,

And so the general of hot desire,

Was sleeping by a virgin hand disarmed.

This brand she quenched in a cool well by,

Which from Love's fire took heat perpetual,

Growing a bath and healthful remedy,

For men discased, but I my mistress' thrall,

Came there for cure and this by that I prove,

Love's fire heats water, water cools not love.

Henry Wriothesley: Excerpts from his Wikipedia page:

Henry Wriothesley (1573-1624) was the only son of Henry Wriothesley, the second

Earl of Southampton, by Mary Browne, the only daughter of Anthony Browne, the

first Viscount Montague, and his first wife, Jane Radcliffe. When his father

died in 1581, the eight-year-old Henry Wriothesley became the third Earl of

Southampton and inherited land that generated income valued at £1097 per annum.

In October 1585, at age twelve, Southampton entered St John's College,

Cambridge, graduating M.A. at age sixteen in 1589. By 1590 Lord Burghley was

negotiating with Southampton's grandfather, Anthony Browne, Viscount Montague,

and Southampton's mother, Mary, for a marriage between Southampton and Lord

Burghley's eldest granddaughter, Elizabeth Vere, daughter of Burghley's

daughter, Anne Cecil, and Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. However the match was

not to Southampton's liking, and in a letter written in November 1594, about six

weeks after Southampton had turned 21, the Jesuit Henry Garnet reported the

rumor that 'The young Erle of Southampton refusing the Lady Veere payeth £5000

of present payment'.

In 1591 Lord Burghley's Clerk in Chancery, John Clapham, dedicated a poem

"Narcissus" to Southampton. According to Akrigg, Southampton was now spending

much of his time at court. He was in attendance when Queen Elizabeth visited

Oxford in late September 1592, and was praised fulsomely in a poem written by

John Sanford to commemorate the Queen's visit. In 1593, George Peele referred to

him as "Gentle Wriothesley, Southampton's star."

In 1593-1593 Shakespeare dedicated his poems "Venus and Adonis" and "The Rape of

Lucrece" to Southampton. The dedication to "The Rape of Lucrece" is couched in

especially extravagant terms: "The love I dedicate to your lordship is without

end ... What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all

I have, devoted yours."

Nathan Drake, in Shakespeare and his Times, was the first to suggest that

Southampton was not only the dedicatee of Shakespeare's two long narrative

poems, but also the 'Fair Youth' of the Sonnets. The title page refers to the 'onlie

begetter of these insuing sonnets Mr W.H.,' and it had earlier been inferred

that the Sonnets were addressed to 'Mr. W.H.' But there is no conclusive

evidence either way.

Southampton received dedications from other writers in the 1590s. On 27 June

1593 Thomas Nashe completed his picaresque novel, The Unfortunate Traveller, and

dedicated it to Southampton, calling him 'a dere lover and cherisher . . . as

well of the lovers of Poets, as of Poets themselves.' In 1593 Barnabe Barnes

published a dedicatory sonnet to Southampton. In 1595 Gervase Markham included a

dedicatory sonnet to Southampton in The Most Honorable Tragedy of Richard Grinvile, Knight. In 1596 John Florio, who was for some years in the Earl's 'pay

and patronage', complimented Southampton on his fluency in Italian, saying he

'had become so complete a master of Italian as to have no need of travel abroad

to perfect his mastery of that tongue'. In 1597 Henry Lok included a sonnet to

Southampton among the sixty dedicatory sonnets in his Sundry Christian Passions.

In the same year William Burton dedicated a translation to him.

In 1595, Southampton jousted in Queen Elizabeth's accession day tournament,

earning a mention in George Peele's Anglorum Feriae as 'gentle and debonaire'.

In 1599, during the Nine Years War (1595–1603), Southampton went to Ireland with

Essex, who made him General of the Horse, but the Queen insisted that the

appointment be cancelled. Southampton remained in personal attendance upon the

Earl, rather than as an officer. However, Southampton was active during the

campaign and prevented a defeat at the hands of the Irish rebels when his

cavalry drove off an attack at Arklow in County Wicklow. Shortly after the Essex

rebellion in February 1601, William Reynolds, a soldier who had served with

Essex in Ireland, mentioned Southampton in a letter to Sir Robert Cecil. He

accused Southampton of hugging other men and playing "wantonly" with them. He

also strongly suggested that the two Earl were willing to pay for sexual favors.

On his return from Ireland, Southampton attracted notice as a playgoer. 'My Lord

Southampton and Lord Rutland,' wrote Rowland Whyte to Sir Robert Sydney in 1599,

'come not to the court: the one doth but very seldom. They pass away the time in

London merely in going to plays every day'.

Southampton was deeply involved in the Essex rebellion in 1601, and in February

1601 was sentenced to death. Cecil obtained the commutation of the penalty to

imprisonment for life.

On the accession of James I, Southampton resumed his place at court and received

numerous honors from the new king. On the eve of the abortive rebellion of Essex

he had induced the players at the Globe Theatre to revive Richard II, and on his

release from prison in 1603 he resumed his connection with the stage. In January

1605 he entertained Queen Anne with a performance of Love's Labour's Lost by

Burbage and his company, to which Shakespeare belonged, at Southampton House.

He seems to have been a born fighter, and engaged in more than one serious

quarrel at court, being imprisoned for a short time in 1603 following a heated

argument with Lord Grey of Wilton in front of Queen Anne. Grey, an implacable

opponent of the Essex faction, was later implicated in the Main Plot and Bye

Plot. Southampton was in more serious disgrace in 1621 for his determined

opposition to Buckingham. He was a volunteer on the Protestant side in Germany

in 1614, and in 1617 he proposed to fit out an expedition against the Barbary

pirates.

Southampton was a leader among the Jacobean aristocrats who turned to modern

investment practices — "in industry, in modernizing their estates and in

overseas trade and colonization." He financed the first tinplate mill in the

country, and founded an ironworks at Titchfield. He developed his properties in

London, in Bloomsbury and Holborn; he revamped his country estates, participated

in the efforts of the East India Company and the New England Company, and backed

Henry Hudson's search for the Northwest Passage.

A significant artistic patron in the Jacobean as well as the Elizabethan era,

Southampton promoted the work of George Chapman, Samuel Daniel, Thomas Heywood,

and the composer Alfonso Ferrabosco the younger. Heywood's popular, expansionist

dramas were compatible with Southampton's maritime and colonial interests.

Henry Wriothesley, whose name is included in the 1605 panel of the New World

Tapestry, took a considerable share in promoting the colonial enterprises of the

time, and was an active member of the Virginia Company's governing council.

Although profits proved elusive, his other visions for the Colony based at

Jamestown were eventually accomplished. He was part of a faction within the

company with Sir Edwin Sandys, who eventually became the Treasurer, and worked

tirelessly to support the struggling venture. In addition to profits,

Southampton's faction sought a permanent colony which would enlarge British

territory, relieve the nation's overpopulation, and expand the market for

English goods. Although profits largely eluded the Virginia Company, and it was

dissolved in 1624, the other goals were accomplished.

His name is thought by many to be the origin of the naming of the harbor of

Hampton Roads, and the Hampton River. Although named at later dates, similar

attribution may involve the town (and later city) of Hampton, Virginia, as well

as Southampton County, Virginia and Northampton County. However, the name

Southampton was not uncommon in England, including an important port city and an

entire region along the southern coast, which was originally part of Hampshire.

There are also variations applied in other areas of the English colonies which

were not part of the Virginia Company of London's efforts, making the origin of

the word and derivations of it as applied in Virginia even more debatable.

In 1624 Southampton was one of four Englishmen appointed to command English

troops fighting in the Low Countries against the Spanish. Shortly after their

arrival, James, the earl's eldest son, succumbed to a fever at Rosendael; five

days later on 10 November 1624, Southampton died of the same cause at

Bergen-op-Zoom. Both were buried in the parish church of Titchfield, Hampshire.

In August 1598 Southampton secretly married Elizabeth Vernon, the daughter of

John Vernon of Hodnet, Shropshire, by his wife Elizabeth Devereux. Elizabeth

Devereux's grandfathers were the Viscount Hereford and the Earl of Huntingdon;

on her father John's side, Elizabeth's family were more obscure.

They had several children, including:

Penelope Wriothesley, who married William Spencer, 2nd Baron Spencer of

Wormleighton.

James Wriothesley, Lord Wriothesley (1 March 1605 – 5 November 1624), who

predeceased his father.

Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton (10 March 1607 – 16 May 1667).

Anne Wriothesley, who married Robert Wallop (20 July 1601 – 19 November 1667) of

Farley Wallop.

There exist numerous portraits of Southampton, in which he is depicted with dark

auburn hair and blue eyes, compatible with Shakespeare's description of "a man

right fair." Sir John Beaumont wrote a well-known elegy in his praise, and

Gervase Markham wrote of him in a tract entitled Honor in his Perfection, or a

Treatise in Commendation of ... Henry, Earl of Oxenford, Henry, Earle of

Southampton, Robert, Earl of Essex (1624).

In 2002 a portrait in the Cobbe collection was identified as a portrait of the

youthful Earl (see below), now known as the Cobbe portrait of Southampton.

In April 2008, a rare portrait, believed to be of Southampton has been

discovered using X-ray technology. Art historians from Bristol University have

found what they believe is a picture of Henry Wriothesley which was painted over

in the sixteenth century. To the naked eye, it is a portrait of his wife

Elizabeth Vernon, dressed in black and wearing ruby ear-rings. The hidden

picture was uncovered when the work was X-rayed in preparation for an exhibition

in Somerset.

References:

Is Shakespeare Dead? by Mark Twain

Was Edward de Vere the real Shakespeare?

The HyperTexts