The HyperTexts

Not his finest hour: The dark side of Winston Churchill

includes a Winston Churchill Timeline/Chronology with Racist Churchill Quotes

Winston Churchill's beliefs about race may be summed up in

this Hitleresque statement: "I do not apologize for the takeover of the region

by the Jews from the Palestinians in the same way I don’t apologize for the

takeover of America by the whites from the Red Indians or the takeover of

Australia from the blacks. It is natural for a superior race to

dominate an inferior one."

by Johann Hari, with an introduction by Michael R. Burch, an editor and

publisher of Holocaust and Nakba poetry, a peace activist, and the author of the

Burch-Elberry Peace Initiative

I believe Johann Hari's article is very important, if we are to understand how

the imperialism, racism and fascism of men like Winston Churchill would,

decades later, lead to events like 9-11 and the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and

Iraq. Churchill is almost universally revered in Western circles for his

dramatic stand and eloquent speeches against Hitler and the Nazis. But in other areas of the world, Churchill has been seen as a man very

similar to Hitler, as have George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Donald

Rumsfeld. I first became aware of Churchill's "dark side" when I studied his

words and actions during his stint as British Colonial Secretary from 1921 to

1922. At that time, just after World War I, the British Empire had peaked in

size with the addition of territories taken from its vanquished enemies.

Approximately one quarter of the world's land and population now fell within the

spheres of British influence. As Colonial Secretary, Churchill had enormous power.

Unfortunately, the man's hubris and insensitivity to the rights of people with

darker skin was astonishing. As

Churchill himself recalled, he "created Jordan with a stroke of a pen one Sunday

afternoon," putting multitudes of Jordanians under the thumb of a throneless

Hashemite prince, Abdullah, whose brother Faisal was awarded another arbitrary patch

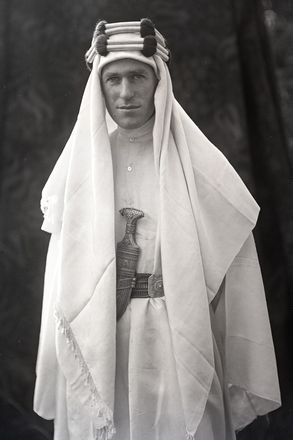

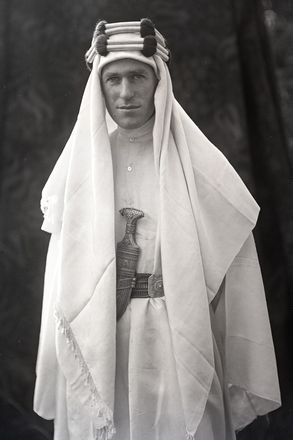

of land that became Iraq. Faisal and Abdullah were war buddies of Churchill's

pal T. E. Lawrence, the famous "Lawrence of Arabia" (who was called "the wild

ass of the desert" by some of his detractors). Lawrence would later call the

1921 Cairo conference his finest hour, because he was able to fulfill his

promises to the Hashemite king Hussein and his sons. But the lines drawn in the

sand by British imperialists were hardly stable, as large numbers of Jordanians,

Iraqis, Kurds and Palestinians were denied anything resembling real democracy.

The huge zigzag in Jordan's eastern border with

Saudi Arabia has been called "Winston's Hiccup" or "Churchill's Sneeze" because

Churchill allegedly drew the expansive boundary after a generous lunch. —

Michael R. Burch

T.E. Lawrence was the most influential delegate at the Cairo conference,

which convened formally on the morning of Saturday, March 12, 1921. Winston

Churchill had arranged the conference without inviting a single Arab (which is

not surprising because in his memoirs Churchill said that he never consulted the

Arabs about his imperial plans for them).

Government House reception in Jerusalem on March 28th 1921. From the left to

right on the front row: Emir Abdullah I of Transjordan, Sir Herbert Samuel,

Winston Churchill, Clementine Churchill, T. E. Lawrence.

Why didn't Churchill invite a single Arab to such an important conference

where their fates would be decided? We get a clear picture of Churchill’s

disdain for Arabs in his 1899 book The River War, in which he wrote:

"How dreadful are the curses which Mohammedanism lays on its votaries! Besides

the fanatical frenzy, which is as dangerous in a man as hydrophobia [rabies] in

a dog, there is this fearful fatalistic apathy."

Before presenting Johann Hari's article, here is a Timeline of Winston

Churchill's actions during his tenure as Colonial Secretary for the British

Empire. The primary source for this timeline was Churchill: A Life by

Martin Gilbert.

Winston Churchill Timeline

• On January 8, 1921, a month before formally becoming the

Secretary of State for the British Colonies, Churchill decides to cut the budget

for the Middle East in half. Churchill wanted to create regional governments

that would not make "undue demands" on Britain. Despite his many orations about

democracy, Churchill opined that Western political methods "are not necessarily

applicable to the East, and basis of election should be framed".

• In February the new Colonial Secretary plans to visit Egypt for a conference

in Cairo. Lord Milner warns Herbert Samuel, the British High Commissioner in

Palestine, that Churchill is "too apt to make up his mind without sufficient

knowledge."

• On March 12, 1921 the Cairo conference begins. The British "experts" include

T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), Sir Percy Cox and Gertrude Bell.

Churchill described the meeting as one of "Forty Thieves" and spent his leisure

time practicing his new hobby of oil painting. During a break he did paintings

of the pyramids. Churchill slashes the region's budget and sets up friends of T.

E. Lawrence as puppet rulers of the artificially created nations of Jordan and

Iraq. These hasty, ill-advised, imperialistic decisions would lead to many

serious problems, including ever-escalating hostilities between Zionists and

Palestinians.

• On March 23, 1921 the conference moves to Jerusalem. Churchill promises the

just-appointed puppet ruler of Transjordan, King Abdullah, that the rights of

Palestine's non-Jewish population would be protected, that no Arabs would be

dispossessed. Was Churchill deliberately lying, or was he so naive that he

didn't understand the real goals of the Zionists? In either case, the statement

was as false as false can be.

• On March 29, 1921 at a Jerusalem ceremony, Churchill plants a tree at the site

of the future Hebrew University and promises that Palestine will be happy and

prosperous, a "paradise." More lies, or incredible naïveté.

• On March 31, 1921 the impetuous Churchill rushes to catch an Italian ship

leaving for Genoa. In less than three weeks he has done damage that will last a

century, or longer.

• On May 31, 1921 the great orator and proponent of democracy announces during a

cabinet meeting that he will suspend the development of "representative

institutions" (i.e., democracy) in Palestine.

• On June 14, 1921 in a speech before the House of Commons, Churchill insisted

that Arab fears of being dispossessed of their land were "illusory." But of

course their fears were entirely valid. Only eight days later, Churchill told

the Canadian Prime Minister that if the Jews became the majority they would

"naturally take it over." But there was nothing "natural" about the Zionists

creating an artificial Jewish majority by ethnically cleaning hundreds of

thousands of Palestinians, which is what would happen just a few years later, in

1948.

• On November 12, 1921 after riots that left five people dead, Churchill told

his advisers not to forget that "everything else that happens in the Middle East

is secondary to reduction in expense." Churchill cared more about money than the

lives of Palestinians and Jews. But when there were riots in Ireland, Churchill

was very concerned about reconciling the hostile factions.

• On July 4, 1922 while Americans were celebrating their independence, Churchill

was lobbying the House of Commons to deny Palestinians any chance of real

democracy or independence, as he supported the creation of Jewish National

Home in Palestine. Even worse, he supported the Zionists having a monopoly over

the development of water power in Palestine, even though Palestinians were much

more numerous than Jews. Once again, Churchill was willing to throw democracy

out the window in the Middle East. Churchill had his way, and another nail was

driven into the coffin of Palestinian rights. A few months later, in October

1922, Churchill would lose his appendix and office in quick succession. But he

certainly did a lot of damage during his short stint as Colonial Secretary.

Winston Churchill Racist and Imperialistic Quotes

"Everywhere one looks, one finds Churchill dripping blood from his mouth. He

was fanatical about violence."

• Churchill's beliefs about race may be summed up in this Hitleresque statement:

"I do not apologize for the takeover of the region by the Jews from the

Palestinians in the same way I don’t apologize for the takeover of America by

the whites from the Red Indians or the takeover of Australia from the blacks. It

is natural for a superior race to dominate an inferior one."

• Churchill told the Palestine Royal Commission: "I do not admit for instance,

that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black

people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people

by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more

worldly wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place."

• Churchill sounded suspiciously like Hitler when he said that his country's

"Aryan stock is bound to triumph."

• Churchill sounded like the KKK when he said that "Keep England White" was a

good slogan.

• Leopold Amery, the British Secretary of State for India, wrote in his diary

that "on the subject of India, Winston is not quite sane" and that he didn't

"see much difference between [Churchill's] outlook and Hitler's."

• Churchill called Gandhi a "half naked seditious fakir."

• Churchill was not much concerned with the deaths of Indians: "Starvation of

anyhow underfed Bengalis is less serious than that of sturdy Greeks."

• Churchill had similar ideas about China: "I think we shall have to take the

Chinese in hand and regulate them."

• Churchill was very consistent in his hatred of Orientals: "We shall wipe them

out, every one of them, men, women, and children. There shall not be a Japanese

left on the face of the earth."

• Churchill, like Hitler, advocated the forced sterilization of the

"feeble-minded" and "insane."

• Churchill once again sounds like Hitler: "I propose that 100,000 degenerate

Britons should be forcibly sterilized and others put in labour camps to halt the

decline of the British race."

• Churchill also disdained the natives of India, saying: "I hate Indians. They

are a beastly people with a beastly religion."

• Churchill blamed Indians for a famine they suffered, claiming they "breed like

rabbits."

• Churchill referred disparagingly to Palestinians as "barbaric hordes who ate

little but camel dung."

• Churchill boasted of personally killing three Sudanese "savages."

• Churchill said, "I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against

uncivilised tribes."

• According to Warren Dockter, a research fellow at the University of Cambridge

and the author of Winston Churchill and the Islamic World, Churchill

was in favour of using mustard gas against Ottoman troops in WWI.

• While the rest of the world was sickened by World War I, an enthusiastic

Churchill wrote: "I would not be out of this glorious delicious war for anything

the world could give me."

• Churchill was the ultimate warmongering imperialist, writing to a friend: "I

think a curse should rest on me — because I love this war. I know it's smashing

and shattering the lives of thousands every moment — and yet — I can't help it —

I enjoy every second of it."

Not his finest hour: The dark side of Winston Churchill

by Johann Hari

Winston Churchill is rightly remembered for leading Britain through her

finest hour – but what if he also led the country through her most shameful

hour? What if, in addition to rousing a nation to save the world from the Nazis,

he fought for a raw white supremacism and a concentration camp network of his

own? This question burns through Richard Toye's new history, Churchill's Empire,

and is even seeping into the Oval Office.

George W. Bush left a bust of Churchill near his desk in the White House, in

an attempt to associate himself with the war leader's heroic stand against

fascism. Barack Obama had it returned to Britain. It's not hard to guess why:

his Kenyan grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama, was imprisoned without trial for

two years and was tortured on Churchill's watch, for resisting Churchill's

empire.

Can these clashing Churchills be reconciled? Do we live, at the same time, in

the world he helped to save, and the world he helped to trash? Toye, one of

Britain's smartest young historians, has tried to pick through these questions

dispassionately – and he should lead us, at last and at least, to a more mature

conversation about our greatest national icon.

Churchill was born in 1874 into a Britain that was washing the map pink, at

the cost of washing distant nations blood red. Victoria had just been crowned

Empress of India, and the scramble for Africa was only a few years away. At

Harrow School and then Sandhurst, he was told a simple story: the superior white

man was conquering the primitive, dark-skinned natives, and bringing them the

benefits of civilisation. As soon as he could, Churchill charged off to take his

part in "a lot of jolly little wars against barbarous peoples". In the Swat

valley, now part of Pakistan, he experienced, fleetingly, a crack of doubt. He

realised that the local population was fighting back because of "the presence of

British troops in lands the local people considered their own," just as Britain

would if she were invaded. But Churchill soon suppressed this thought, deciding

instead they were merely deranged jihadists whose violence was explained by a

"strong aboriginal propensity to kill".

He gladly took part in raids that laid waste to whole valleys, destroying

houses and burning crops. He then sped off to help reconquer the Sudan, where he

bragged that he personally shot at least three "savages".

The young Churchill charged through imperial atrocities, defending each in

turn. When concentration camps were built in South Africa, for white Boers, he

said they produced "the minimum of suffering". The death toll was almost 28,000,

and when at least 115,000 black Africans were likewise swept into British camps,

where 14,000 died, he wrote only of his "irritation that Kaffirs should be

allowed to fire on white men".

Later, he boasted of his experiences there: "That

was before war degenerated. It was great fun galloping about."

Then as an MP he demanded a rolling programme of more conquests, based on his

belief that "the Aryan stock is bound to triumph". There seems to have been an

odd cognitive dissonance in his view of the "natives". In some of his private

correspondence, he appears to really believe they are helpless children who will

"willingly, naturally, gratefully include themselves within the golden circle of

an ancient crown".

But when they defied this script, Churchill demanded they be crushed with

extreme force. As Colonial Secretary in the 1920s, he unleashed the notorious

Black and Tan thugs on Ireland's Catholic civilians, and when the Kurds rebelled

against British rule, he said: "I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas

against uncivilised tribes...[It] would spread a lively terror."

Of course, it's easy to dismiss any criticism of these actions as

anachronistic. Didn't everybody think that way then? One of the most striking

findings of Toye's research is that they really didn't: even at the time,

Churchill was seen as at the most brutal and brutish end of the British

imperialist spectrum. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was warned by Cabinet

colleagues not to appoint him because his views were so antediluvian. Even his

startled doctor, Lord Moran, said of other races: "Winston thinks only of the

colour of their skin."

Many of his colleagues thought Churchill was driven by a deep loathing of

democracy for anyone other than the British and a tiny clique of supposedly

superior races. This was clearest in his attitude to India. When Mahatma Gandhi

launched his campaign of peaceful resistance, Churchill raged that he "ought to

be lain bound hand and foot at the gates of Delhi, and then trampled on by an

enormous elephant with the new Viceroy seated on its back."

As the resistance

swelled, he announced: "I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly

religion." This hatred killed. To give just one, major, example, in 1943 a

famine broke out in Bengal, caused – as the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has proved – by the imperial policies of the British. Up to

three

million people starved to death while British officials begged Churchill to

direct food supplies to the region. He bluntly refused. He raged that it was

their own fault for "breeding like rabbits".

At other times, he said the plague

was "merrily" culling the population.

Skeletal, half-dead people were streaming into the cities and dying on the

streets, but Churchill – to the astonishment of his staff – had only jeers for

them. This rather undermines the claims that Churchill's imperialism was

motivated only by an altruistic desire to elevate the putatively lower races.

Hussein Onyango Obama is unusual among Churchill's victims only in one

respect: his story has been rescued from the slipstream of history, because his

grandson ended up as President of the US. Churchill believed that Kenya's

fertile highlands should be the preserve of the white settlers, and approved the

clearing out of the local "blackamoors". He saw the local Kikuyu as "brutish

children". When they rebelled under Churchill's post-war premiership, some

150,000 of them were forced at gunpoint into detention camps – later dubbed

"Britain's gulag" by Pulitzer-prize winning historian, Professor Caroline

Elkins. She studied the detention camps for five years for her remarkable book

Britain's Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya, explains the tactics adopted

under Churchill to crush the local drive for independence. "Electric shock was

widely used, as well as cigarettes and fire," she writes. "The screening teams

whipped, shot, burned, and mutilated Mau Mau suspects." Hussein Onyango Obama

never truly recovered from the torture he endured.

Many of the wounds Churchill inflicted have still not healed: you can find

them on the front pages any day of the week. He is the man who invented Iraq,

locking together three conflicting peoples behind arbitrary borders that have

been bleeding ever since. He is the Colonial Secretary who offered the

Over-Promised Land to both the Jews and the Arabs – although he seems to have

privately felt racist contempt for both. He jeered at the Palestinians as

"barbaric hordes who ate little but camel dung," while he was appalled that the

Israelis [Jews who migrated to Palestine] "take it for granted that the local population will be cleared out to

suit their convenience".

True, occasionally Churchill did become queasy about some of the most extreme

acts of the Empire. He fretted at the slaughter of women and children, and

cavilled at the Amritsar massacre of 1919. Toye tries to present these doubts as

evidence of moderation – yet they almost never seem to have led Churchill to

change his actions. If you are determined to rule people by force against their

will, you can hardly be surprised when atrocities occur. Rule Britannia would

inexorably produce a Cruel Britannia.

So how can the two be reconciled? Was Churchill's moral opposition to Nazism

a charade, masking the fact he was merely trying to defend the British Empire

from a rival?

The US civil rights leader Richard B. Moore, quoted by Toye, said it was "a

rare and fortunate coincidence" that at that moment "the vital interests of the

British Empire [coincided] with those of the great overwhelming majority of

mankind". But this might be too soft in its praise. If Churchill had only been

interested in saving the Empire, he could probably have cut a deal with Hitler.

No: he had a deeper repugnance for Nazism than that. He may have been a thug,

but he knew a greater thug when he saw one – and we may owe our freedom today to

this wrinkle in history.

This, in turn, led to the great irony of Churchill's life. In resisting the

Nazis, he produced some of the richest prose-poetry in defence of freedom and

democracy ever written. It was a cheque he didn't want black or Asian people to

cash – but they refused to accept that the Bank of Justice was empty. As the

Ghanaian nationalist Kwame Nkrumah wrote: "All the fair, brave words spoken

about freedom that had been broadcast to the four corners of the earth took seed

and grew where they had not been intended." Churchill lived to see democrats

across Britain's dominions and colonies – from nationalist leader Aung San in

Burma to Jawarlal Nehru in India – use his own intoxicating words against him.

Ultimately, the words of the great and glorious Churchill who resisted

dictatorship overwhelmed the works of the cruel and cramped Churchill who tried

to impose it on the darker-skinned peoples of the world. The fact that we now

live in a world where a free and independent India is a superpower eclipsing

Britain, and a grandson of the Kikuyu "savages" is the most powerful man in the

world, is a repudiation of Churchill at his ugliest – and a sweet, ironic

victory for Churchill at his best.

For updates on this issue and others, follow Johann at

www.twitter.com/johannhari101

'Churchill's Empire' is published by Macmillan (£25). To order a copy for the

special price of £22.50 (free P&P) call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600

030, or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel, was a British politician and

diplomat. He was the first High Commissioner of Palestine. He had a religious

Jewish upbringing and despite renouncing all religious belief, he remained a

member of the Jewish community, and kept kosher and the Sabbath "for hygienic

reasons." He put forward the idea of establishing a British Protectorate over

Palestine, and his ideas influenced the Balfour Declaration. Two months after

Britain's declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914, Samuel

circulated a memorandum entitled "The Future of Palestine" to his cabinet

colleagues, suggesting that Palestine become a home for the Jewish people under

British Rule. The memorandum stated: "I am assured that the solution of the

problem of Palestine which would be much the most welcome to the leaders and

supporters of the Zionist movement throughout the world would be the annexation

of the country to the British Empire". In other words, the British Empire could

expand with Britain-friendly Jews in charge! In 1917, Britain occupied Palestine

(then part of the Ottoman Empire) during World War I. Samuel was appointed to

the position of High Commissioner in 1920 and served until 1925. Samuel became

the first Jew to govern the historic land of Israel in 2,000 years. Samuel's

appointment to High Commissioner of Palestine was controversial. While the

Zionists welcomed the appointment of a Zionist Jew to the post, the military

government, headed by Allenby and Bols, called Samuel's appointment "highly

dangerous".[5] Technically, Allenby noted, the appointment was illegal, in that

a civil administration that would compel the inhabitants of an occupied country

to express their allegiance to it before a formal peace treaty (with Turkey) was

signed, was in violation of both military law and the Hague Convention.[6] Bols

said the news was received with '(c)onsternation, despondency, and exasperation'

by the Moslem [and] Christian population ... They are convinced that he will be

a partisan Zionist and that he represents a Jewish and not a British

Government.'[7] Allenby said that the Arabs would see it as "as handing country

over at once to a permanent Zionist Administration" and predicted numerous

degrees of violence. Lord Curzon read this last message to Samuel and asked him

to reconsider accepting the post. (Samuel took advice from a delegation

representing the Zionists which was in London at the time, who told him that

these 'alarmist' reports were not justified. The wisdom of appointing Samuel was

debated in the House of Lords a day before he arrived in Palestine. Lord Curzon

said that no 'disparaging' remarks had been made during the debate, but that

'very grave doubts have been expressed as to the wisdom of sending a Jewish

Administrator to the country at this moment'. Questions in the House of Commons

of the period also show much concern about the choice of Samuel, asking amongst

other things 'what action has been taken to placate the Arab population ... and

thereby put an end to racial tension'. Three months after his arrival, The

Morning Post wrote that 'Sir Herbert Samuel's appointment as High Commissioner

was regarded by everyone, except Jews, as a serious mistake.' Samuel's role in

Palestine is still debated. According to Bernard Wasserstein, "He is remembered

kindly neither by the majority of Zionist historians, who tend to regard him as

one of the originators of the process whereby the Balfour Declaration in favour

of Zionism was gradually diluted and ultimately betrayed by Great Britain, nor

by Arab nationalists who regard him as a personification of the alliance between

Zionism and British imperialism and as one of those responsible for the

displacement of the Palestinian Arabs from their homeland. In fact, both are

mistaken."

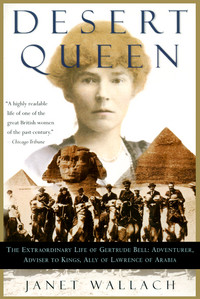

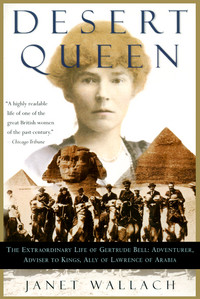

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell (1868-1926) was an English writer, poet,

translator of Hafiz, world traveller, political officer, administrator,

archaeologist and spy. A British expert on the Middle East, along with T. E.

Lawrence (the famous "Lawrence of Arabia"), Bell helped establish the Hashemite

dynasties in Jordan and Iraq.

She played a major role in establishing and helping administer the modern state

of Iraq, utilizing her unique perspective from her travels and relations with

tribal leaders throughout the Middle East. During her lifetime she was highly

esteemed and trusted by British officials and given an immense amount of power

for a woman at the time. She has been described as "one of the few

representatives of His Majesty's Government remembered by the Arabs with

anything resembling affection".

Bell was born in Washington Hall, County Durham, England to a family whose

wealth enabled her travels. She was described as having "reddish hair and

piercing blue-green eyes". Her personality was characterized by energy,

intellect, and a thirst for adventure. Her grandfather was the ironmaster Sir

Isaac Lowthian Bell, an industrialist and a Liberal Member of Parliament, in

Benjamin Disraeli's second term. His role in British policy-making exposed

Gertrude at a young age to international matters and most likely encouraged her

curiosity for the world, and her later involvement in international politics.

Bell received her early education from Queen's College in London and then later

at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University at age 17. She specialized in modern

history, in which she received a first class honours degree in two years.

(History was one of the few subjects women were allowed to study at that time.)

Bell never married. She had an unconsummated affair with Maj. Charles

Doughty-Wylie, a married man, with whom she exchanged love letters from

1913-1915. Upon his death in 1915 at Gallipoli, Bell devoted herself to her

work.

Bell's uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles, was British minister (similar to ambassador)

at Tehran, Persia. In May 1892, after leaving Oxford, Bell travelled to Persia

to visit him. She described this journey in her book, Persian Pictures, which

was published in 1894. She spent much of the next decade travelling around the

world, mountaineering in Switzerland, and developing a passion for archaeology

and languages. She had become fluent in Arabic, Persian, French and German as

well as also speaking Italian and Turkish. In 1899, Bell again went to the

Middle East. She visited Palestine and Syria that year and in 1900, on a trip

from Jerusalem to Damascus, she became acquainted with the Druze living in Jabal

al-Druze. She traveled across Arabia six times over the next 12 years.

In January 1909, she visited the Hittite city of Carchemish, where she mapped

and described the ruin of Ukhaidir and consulted with the archaeologists on

site. One of them was T. E. Lawrence.

Ironically, Bell was involved in anti-feminist activities and became the

honorary secretary of the British Women's Anti-Suffrage League. Her stated

reason for her anti-suffrage stand was that as long as women felt that the

kitchen and the bedroom were their only domains, they were truly unprepared to

take part in deciding how a nation should be ruled.

At the outbreak of World War I, Bell's request for a Middle East posting was

initially denied. She instead volunteered with the Red Cross in France. Later,

she was asked by British Intelligence to help get soldiers through the deserts,

and from the World War I period until her death she was the only woman holding

political power and influence in shaping British imperial policy in the Middle

East. She often acquired a team of locals which she directed and led on her

expeditions. Throughout her travels Bell established close relations with tribe

members across the Middle East.

In November 1915 she was summoned to Cairo to the nascent Arab Bureau, headed by

General Gilbert Clayton, where she once again met T. E. Lawrence. At first she

did not receive an official position, but helped Lt. Cmdr. David Hogarth set

about organizing and processing her own, Lawrence's and Capt. W. H. I.

Shakespear's data about the location and disposition of Arab tribes that could

be encouraged to join the British against the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence and the

British used the information in forming alliances with the Arabs.

On March 3, 1916, Gen. Clayton sent Bell to Basra, which British forces had

captured in November 1914, to advise Chief Political Officer Percy Cox regarding

an area she knew better than any other Westerner. She drew maps to help the

British army reach Baghdad safely. She became the only female political officer

in the British forces and received the title of "Liaison Officer, Correspondent

to Cairo". She was Harry St. John Philby's field controller, and taught him the

finer arts of behind-the-scenes political manoeuvering.

When British troops took Baghdad on March 10, 1917, Bell was summoned by Cox to

Baghdad and given the title of "Oriental Secretary." She, Cox and Lawrence were

among a select group of "Orientalists" convened by Winston Churchill to attend a

1921 Conference in Cairo to determine the boundaries of the British mandate.

Throughout the conference, she, Cox and Lawrence worked tirelessly to promote

the establishment of the countries of Transjordan and Iraq to be presided over

by the Kings Abdullah and Faisal, sons of the instigator of the Arab Revolt

against the Ottoman Empire (ca. 1915-1916), Hussein bin Ali, Sharif and Emir of

Mecca. Until her death in Baghdad, she served in the Iraq British High

Commission advisory group there.

Referred to by Iraqis as "al-Khatun" (a Lady of the Court who keeps an open eye

and ear for the benefit of the State), she was a confidante of King Faisal of

Iraq and helped ease his passage into the role.

Her work was specially mentioned in the British Parliament, and she was awarded

the Order of the British Empire. Some consider the present troubles in Iraq are

derived from the lines Bell helped draw to create its borders. Perhaps so, but

her reports indicate that problems were foreseen, and that it was clearly

understood that there were just not many (if any) permanent solutions for

calming the divisive forces at work in that part of the world.

As the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire was finalized by the end of the war in

late January 1919, Bell was assigned to conduct an analysis of the situation in

Mesopotamia. Due to her familiarity and relations with the tribes in the area

she had strong ideas about the leadership needed in Iraq. She spent the next ten

months writing what was later considered a masterful official report, "Self

Determination in Mesopotamia". On October 11, 1920, Percy Cox returned to

Baghdad and asked her to continue as Oriental Secretary, acting as liaison with

the forthcoming Arab government. She essentially played the role of mediator

between the Arab government and British officials.

Throughout the early 1920s Bell was an integral part of the administration of

Iraq. However, she did not find working with the new king to be easy: "You may

rely upon one thing — I'll never engage in creating kings again; it's too great

a strain."

Gertrude Bell's first love had always been archaeology, thus she helped form

what became the Baghdad Archaeological Museum, later renamed the Iraqi Museum.

Her goal was to preserve Iraqi culture and history which included the important

relics of Mesopotamian civilizations, and keep them in their country of origin.

She also supervised excavations and examined finds and artifacts. She brought in

extensive collections, such as from the Babylonian Empire. The museum was

officially opened in June 1926, shortly before Bell's death. (After her death,

at the Emir's suggestion, the right wing of the Museum was named as a memorial

to her.) It was extensively looted during the US invasion of 2003.

Bell briefly returned to Britain in 1925, and found herself facing family

problems and ill health. Her family's fortune had begun to decline due to the

onset of post-World War I worker strikes in Britain and economic depression in

Europe. She returned to Baghdad and soon developed pleurisy. When she recovered,

she heard that her younger brother Hugo had died of typhoid. On 12 July 1926,

Bell was discovered dead, of an apparent overdose of sleeping pills. There is

much debate on her death, but it is unknown whether the overdose was an

intentional suicide or accidental since she had asked her maid to wake her.

She never married or had children. Some say the death of Major Charles

Doughty-Wylie affected her for the rest of her life and may have added to a

depressive state. She was buried at the British cemetery in Baghdad's Bab al-Sharji

district. Her funeral was a major event, attended by large numbers of people

including her colleagues, British officials and the King of Iraq. It was said

King Faisal watched the procession from his private balcony as they carried her

coffin to the cemetery.

An obituary written by her peer D. G. Hogarth expressed the respect British

officials held for her. Hogarth honoured her by saying, "No woman in recent time

has combined her qualities – her taste for arduous and dangerous adventure with

her scientific interest and knowledge, her competence in archaeology and art,

her distinguished literary gift, her sympathy for all sorts and condition of

men, her political insight and appreciation of human values, her masculine

vigour, hard common sense and practical efficiency – all tempered by feminine

charm and a most romantic spirit."

In 1927, a year after her death, her stepmother Dame Florence Bell, published

two volumes of Bell's collected correspondence written during the 20 years

preceding World War I.

The British diplomat and Member of Parliament Rory Stewart wrote that "When I

served as a British official in southern Iraq in 2003, I often heard Iraqis

compare my female colleagues to Gertrude Bell. It was generally casual flattery,

and yet the example of Bell and her colleagues was unsettling. More than ten

biographies have portrayed her as the ideal Arabist, political analyst, and

administrator."

Rory Stewart also praised her 1920 White Paper, comparing it to General

Petraeus's report to Congress.

TEACHINGS OF HAFIZ

Translated by Gertrude Lowthian Bell

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE

SHEMSUDDIN MAHOMMAD, better known by his poetical surname of Hafiz, was born in

Shiraz in the early part of the fourteenth century. His names, being

interpreted, signify the Sun of the Faith, the Praiseworthy, and One who can

recite the Koran; he is further known to his compatriots under the titles of the

Tongue of the Hidden and the Interpreter of Secrets. The better part of his life

was spent in Shiraz, and he died in that city towards the close of the century.

The exact date either of his birth or of his death is unknown. He fell upon

turbulent times. His delicate love-songs were chanted to the rude accompaniment

of the clash of arms, and his dreams must have been interrupted often enough by

the nip of famine in a beleaguered town, the inrush of conquerors, and the

flight of the defeated.

Excerpts from TEACHINGS OF HAFIZ

I

ARISE, oh Cup-bearer, rise! and bring

To lips that are thirsting the bowl they praise,

For it seemed that love was an easy thing,

But my feet have fallen on difficult ways.

I have prayed the wind o'er my heart to fling

The fragrance of musk in her hair that sleeps

In the night of her hair-yet no fragrance stays

The tears of my heart's blood my sad heart weeps.

Hear the Tavern-keeper who counsels you:

"With wine, with red wine your prayer carpet dye!"

There was never a traveller like him but knew

The ways of the road and the hostelry.

Where shall I rest, when the still night through,

Beyond thy gateway, oh Heart of my heart,

The bells of the camels lament and cry:

"Bind up thy burden again and depart!"

The waves run high, night is clouded with fears,

And eddying whirlpools clash and roar;

How shall my drowning voice strike their ears

Whose light-freighted vessels have reached the shore?

I sought mine own; the unsparing years

Have brought me mine own, a dishonoured name.

What cloak shall cover my misery o'er

When each jesting mouth has rehearsed my shame!

Oh Hafiz, seeking an end to strife,

Hold fast in thy mind what the wise have writ:

"If at last thou attain the desire of thy life,

Cast the world aside, yea, abandon it!"

II

THE bird of gardens sang unto the rose,

New blown in the clear dawn: "Bow down thy head!

As fair as thou within this garden close,

Many have bloomed and died." She laughed and said

"That I am born to fade grieves not my heart

But never was it a true lover's part

To vex with bitter words his love's repose."

The tavern step shall be thy hostelry,

For Love's diviner breath comes but to those

That suppliant on the dusty threshold lie.

And thou, if thou would'st drink the wine that flows

From Life's bejewelled goblet, ruby red,

Upon thine eyelashes thine eyes shall thread

A thousand tears for this temerity.

Last night when Irem's magic garden slept,

Stirring the hyacinth's purple tresses curled,

The wind of morning through the alleys stept.

"Where is thy cup, the mirror of the world?

Ah, where is Love, thou Throne of Djem?" I cried.

The breezes knew not; but "Alas," they sighed,

"That happiness should sleep so long!" and wept.

Not on the lips of men Love's secret lies,

Remote and unrevealed his dwelling-place.

Oh Saki, come! the idle laughter dies

When thou the feast with heavenly wine dost grace.

Patience and wisdom, Hafiz, in a sea

Of thine own tears are drowned; thy misery

They could not still nor hide from curious eyes.

III

WIND from the east, oh Lapwing of the day,

I send thee to my Lady, though the way

Is far to Saba, where I bid thee fly;

Lest in the dust thy tameless wings should lie,

Broken with grief, I send thee to thy nest,

Fidelity.

Or far or near there is no halting-place

Upon Love's road-absent, I see thy face,

And in thine ear my wind-blown greetings sound,

North winds and east waft them where they are bound,

Each morn and eve convoys of greeting fair

I send to thee.

Unto mine eyes a stranger, thou that art

A comrade ever-present to my heart,

What whispered prayers and what full meed of praise

I send to thee.

Lest Sorrow's army waste thy heart's domain,

I send my life to bring thee peace again,

Dear life thy ransom! From thy singers learn

How one that longs for thee may weep and burn

Sonnets and broken words, sweet notes and songs

I send to thee.

Give me the cup! a voice rings in mine ears

Crying: "Bear patiently the bitter years!

For all thine ills, I send thee heavenly grace.

God the Creator mirrored in thy face

Thine eyes shall see, God's image in the glass

I send to thee.

Hafiz, thy praise alone my comrades sing;

Hasten to us, thou that art sorrowing!

A robe of honour and a harnessed steed

I send to thee."

VI

A FLOWER-TINTED cheek, the flowery close

Of the fair earth, these are enough for me

Enough that in the meadow wanes and grows

The shadow of a graceful cypress-tree.

I am no lover of hypocrisy;

Of all the treasures that the earth can boast,

A brimming cup of wine I prize the most—

This is enough for me!

To them that here renowned for virtue live,

A heavenly palace is the meet reward;

To me, the drunkard and the beggar, give

The temple of the grape with red wine stored!

Beside a river seat thee on the sward;

It floweth past—so flows thy life away,

So sweetly, swiftly, fleets our little day—

Swift, but enough for me!

Look upon all the gold in the world's mart,

On all the tears the world hath shed in vain

Shall they not satisfy thy craving heart?

I have enough of loss, enough of gain;

I have my Love, what more can I obtain?

Mine is the joy of her companionship

Whose healing lip is laid upon my lip—

This is enough for me!

I pray thee send not forth my naked soul

From its poor house to seek for Paradise

Though heaven and earth before me God unroll,

Back to thy village still my spirit flies.

And, Hafiz, at the door of Kismet lies

No just complaint—a mind like water clear,

A song that swells and dies upon the ear,

These are enough for thee!

In depicting the intensity of love, Gertrude Bell thought Hafiz comparable to

the West’s own Shakespeare.

My weary heart eternal silence keeps–

I know not who has slipped into my heart;

Though I am silent, one within me weeps.

My soul shall rend the painted veil apart.

...and...

I have estimated the influence of Reason upon Love

and found that it is like that of a raindrop upon the ocean,

which makes one little mark upon the water’s face and disappears.

The HyperTexts