The HyperTexts

Excerpts from "A Page from the Deportation Diary"

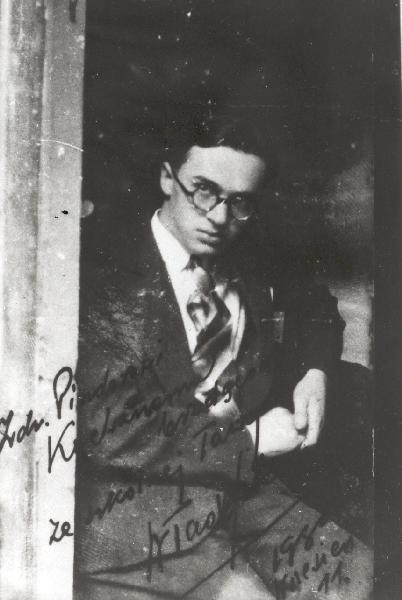

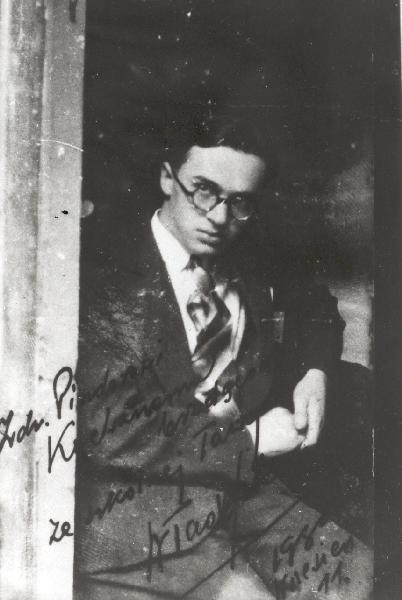

by Wladyslaw Szlengel, a victim of the Holocaust and one of its foremost Poets

Władysław Szlengel (1912-1943) was a Jewish-Polish poet, lyricist, journalist,

and stage actor who was murdered by Nazis during the Holocaust.

For more information about Wladyslaw Szlengel and the role

his courageous friend Dr. Janusz Korczak played in befriending,

watching over and comforting children sent to their deaths by the Nazis, please read the article beneath the poem and follow the links.

Excerpts from "A Page from the Deportation Diary"

by Wladyslaw Szlengel

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I saw Janusz Korczak walking today,

leading the children, at the head of the line.

They were dressed in their best clothes—immaculate, if gray.

Some say the weather wasn’t dismal, but fine.

They were in their best jumpers and laughing (not loud),

but if they’d been soiled, tell me—who could complain?

They walked like calm heroes through the haunted crowd,

five by five, in a whipping rain.

The pallid, the trembling, watched from high overhead,

through barely cracked windows—pale, transfixed with dread.

And now and then, from the high, tolling bell

a strange moan escaped, like a sea gull’s torn cry.

Their “superiors” looked on, their eyes hard as stone.

So let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

Footfalls... then silence... the cadence of feet...

O, who can console them, their last mile so drear?

The church bells peal on, over shocked Leszno Street.

Will Jesus Christ save them? The high bells career.

No, God will not save them. Nor you, friend, nor I.

But let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

No one will offer the price of their freedom.

No one will proffer a single word.

His eyes hard as gavels, the silent policeman

agrees with the priest and his terrible Lord:

“Give them the Sword!”

At the great town square there is no intervention.

No one tugs Schmerling’s sleeve. No one cries

“Rescue the children!” The air, thick with tension,

reeks with the odor of vodka, and lies.

How calmly he walks, with a child in each arm:

Gut Doktor Korczak, please keep them from harm!

A fool rushes up with a reprieve in hand:

“Look Janusz Korczak—please look, you’ve been spared!”

No use for that. One resolute man,

uncomprehending that no one else cared

enough to defend them,

his choice is to end with them.

Translator's note: It seems incomprehensible that the Nazis murdered completely

innocent women and children, and that the German people stood by and

did nothing to stop them. But what if I told you that today the governments of

Israel and the United States have colluded to do something very similar, so that

millions of Palestinian children have been born in chains, and tens of thousands of them

have died without ever drawing a free breath? What if I told you that the

President of the United States, his cabinet, the State Department and

the Joint Chiefs of Staff all know exactly what is happening,

and yet none of them will do anything to help these destitute children, because to admit the

truth would cost American politicians campaign contributions

and votes? How would it make you feel to know that

Americans have been funding and supporting

this new Holocaust, to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars, over the past

fifty years? If you are an American citizen, doesn't this make you complicit, to

some degree, in what is happening to these poor children, who have never done

anything to harm you, me, or anyone else? If this concerns you, as I hope it does, I

have put together an index of articles about this new Holocaust, the

Nakba ("Catastrophe")

of the children of Gaza and Occupied Palestine. In this index you can read what

great humanitarians and Nobel Prize laureates like Gandhi, Albert Einstein, Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr., Jimmy Carter, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu have said

about human rights and the Nakba. I don't believe the United States should do

anything to deny completely innocent women and children equal human rights,

freedom and dignity. Do you? I hope you will choose to follow in the footsteps

of Janusz Korczak and join me and millions of other people in trying to help the children of the Nakba become free, just as American

children are free. And I believe there is something we can do to help. To learn

more, please click here: Peace in the Middle East.

Wladyslaw Szlengel

was born in 1914, in Warsaw. His father, an artist-painter, supported his family

by painting movie posters. While still in school, young Wladyslaw wrote poems and

short stories. A number of them were published in various small magazines.

Later, his works continued to appear, mainly in Warsaw publications. He was also

a songwriter who produced texts for cabarets and he wrote satirical poems for

the press and stage.

Szlengel's writings were firmly grounded in reality. After the creation of the Warsaw

ghetto, they acquired a singular depth. Emanuel

Ringelblum reported that Szlengel's poems "were highly popular in the

ghetto and reflected its moods." They passed from hand to hand and were

recited at meetings. Szlengel also composed works of prose and poetry for Sztuka

(Art), one of the clubs for the emerging elite and the few people of means in

the ghetto. Szlengel's became one of the foremost voices of one of the largest

European Jewish communities, as these lines from "A Cry in the Night"

attest ...

These poems were written between the first

And second upheavals,

In the last dying days of agony

Of the largest Jewish community in Europe ...

Szlengel succeeded in conveying in his writings of that period his views on the

occupiers and his misgivings about the running of the ghetto's institutions.

When the deportations from the Warsaw

ghetto were launched, Szlengel's mood changed. From then on his works

emphasized the terror felt in the ghetto and the bitter settling of accounts

between men and God. One of his poems is entitled "An Account with

God" ...

Do You still expect that

The day after tomorrow like in the Testament

When going to the Prussian gas

I shall still say "Amen" to You?

In the ghetto, each prayer became an "immense plea for mercy, a

miracle" as in the poem "Kol Nidre" ...I've never understood the content and the words,

Only the melody of the prayer.

While my eyes I close, I see again

Reminisces from my childhood

The yellow grayish glow of candle light,

Sad movements of arms and beards,

I hear a cry, wailing

An immense plea for mercy, a miracle ...

Whipping of the chest, clasping hands --

The glory of old books,

Fear of verdicts unknown and dark.

That night I'll never tear off my heart,

A menacing mysterious night,

And the grieved prayer Kol Nidre --

In the poem "Telephone, " Szlengel complains that no one

is left whom he can call in the Polish side of the city. In his last poems,

which he wrote when he was working in a broom workshop, Szlengel records

the decline of the ghetto and its final days. One such poem is "The Little Station:

Treblinka"

(translation by Yala Korwin):

On the Tluszcz-Warsaw line,

from the Warsaw-East station,

you leave by rail

and ride straight on …

The journey lasts, sometimes

five hours & 45 minutes,

but sometimes it lasts

a lifetime until death.

The station is tiny.

Three fir trees grow there.

The sign is ordinary:

it’s the Treblinka station.

No cashier’s window,

No porter in view,

No return tickets,

Not even for a million.

There, no one is waiting,

no one waves a kerchief,

and only silence hovers,

deaf emptiness greets you.

Silent the flagpole,

silent the fir trees,

silent the black sign:

it’s the Treblinka station.

Only an old poster

with fading letters

advises:

“Cook with gas.”

Szlengel was apparently a ghetto policeman for a time, but he resigned, since he was

incapable of taking part in the roundups of ghetto inhabitants conducted by the

ghetto police during the deportations. Even in the final stages of that period,

Szlengel continued to recite his poems before small groups in clandestine

gatherings. In poems like "Five

Minutes to Twelve," Szlengel bids farewell to life, expresses his admiration for those offering resistance

with weapons in their hands, and calls for revenge:

Hear, O God of the Germans,

the Jews praying amid the barbarians,

an iron rod or a grenade in their hands.

Give us, O God, a bloody fight

and let us die a swift death!

Szlengel took part in the September of 1939 campaign against the German

invaders. The only Jewish writer who was still alive in the ghetto, he became

its chronicler. According to surviving evidence, Szlengel was a close friend of Janusz

Korczak.

Szlengel was killed in April 1943. He is known to have been in a bunker during the Warsaw

ghetto uprising, but the circumstances and the exact date of his death are

not known.

The Nazis destroyed the Jewish people and their literary works with equal

fanatical zeal.

Therefore, not much remains of Szlengel’s output. Only part of his poetry and prose writings

has been preserved. A

collection of his writings in Polish was published under the title Co

Czytalem Umarlym (What I Read to The Dead). This slender volume was published in 1977 by Warsaw Publishing

Institute. It begins with an introductory essay of the same title, followed by three one-page

essays, and around forty poems. The introductory essay is a

heart-wrenching account of the ghetto experience. It ends thus:

Do Read it.

This is our history.

This is what I read to the dead …

To read the entire essay, click here.

The HyperTexts