The HyperTexts

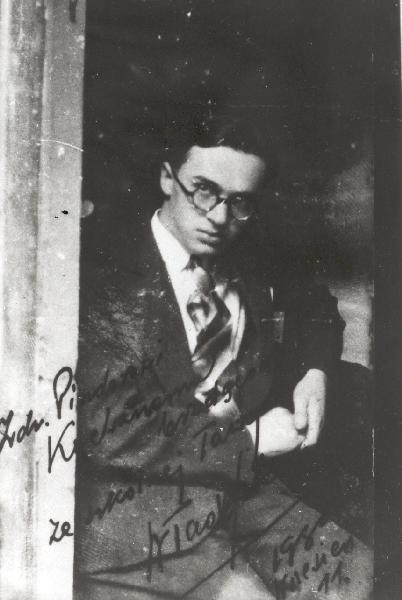

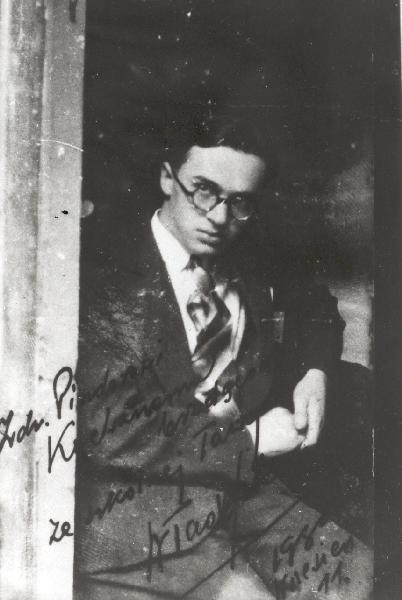

Wladyslaw Szlengel

Wladyslaw Szlengel

was born in 1914, in Warsaw. His father, an artist, supported his family

by painting movie posters. While still in school, young Wladyslaw wrote poems and

short stories. A number of them were published in various small magazines.

Later, his works continued to appear, mainly in Warsaw publications. He was also

a songwriter who produced texts for cabarets and he wrote satirical poems for

the press and stage.

Szlengel's writings were firmly grounded in reality. After the creation of the Warsaw

ghetto, they

acquired a singular depth. A good example is this poem he wrote about a

courageous friend of his who watched over and comforted children the Nazis were

sending to their deaths,

Janusz Korczak:

Excerpts from "A Page from the Deportation Diary"

by Wladyslaw Szlengel

a loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I saw Janusz Korczak walking today,

leading the children, at the head of the line.

They were dressed in their best clothes—immaculate, if gray.

Some say the weather wasn’t dismal, but fine.

They were in their best jumpers and laughing (not loud),

but if they’d been soiled, tell me—who could complain?

They walked like calm heroes through the haunted crowd,

five by five, in a whipping rain.

The pallid, the trembling, watched high overhead,

through barely cracked windows—pale, transfixed with dread.

And now and then, from the high, tolling bell

a strange moan escaped, like a sea gull’s torn cry.

Their “superiors” looked on, their eyes hard as stone.

So let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

Footfall . . . then silence . . . the cadence of feet . . .

O, who can console them, their last mile so drear?

The church bells peal on, over shocked Leszno Street.

Will Jesus Christ save them? The high bells career.

No, God will not save them. Nor you, friend, nor I.

But let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

No one will offer the price of their freedom.

No one will proffer a single word.

His eyes hard as gavels, the silent policeman

agrees with the priest and his terrible Lord:

“Give them the Sword!”

At the town square there is no intervention.

No one tugs Schmerling’s sleeve. No one cries

“Rescue the children!” The air, thick with tension,

reeks with the odor of vodka, and lies.

How calmly he walks, with a child in each arm:

Gut Doktor Korczak, please keep them from harm!

A fool rushes up with a reprieve in hand:

“Look Janusz Korczak—please look, you’ve been spared!”

No use for that. One resolute man,

uncomprehending that no one else cared

enough to defend them,

his choice is to end with them.

Emanuel

Ringelblum reported that Szlengel's poems "were highly popular in the

ghetto and reflected its moods." They passed from hand to hand and were

recited at meetings. Szlengel also composed works of prose and poetry for Sztuka

(Art), one of the clubs for the emerging elite and the few people of means in

the ghetto. Szlengel's became one of the foremost voices of one of the largest

European Jewish communities, as these lines from "A Cry in the Night"

attest ...

These poems were written between the first

And second upheavals,

In the last dying days of agony

Of the largest Jewish community in Europe ...

Szlengel succeeded in conveying in his writings of that period his views on the

occupiers and his misgivings about the running of the ghetto's institutions.

When the deportations from the Warsaw

ghetto were launched, Szlengel's mood changed. From then on his works

emphasized the terror felt in the ghetto and the bitter settling of accounts

between men and God. One of his poems is entitled "An Account with

God" ...

Do You still expect that

The day after tomorrow like in the Testament

When going to the Prussian gas

I shall still say "Amen" to You?

In the ghetto, each prayer became an "immense plea for mercy, a

miracle" as in the poem "Kol Nidre" ...

I've never understood the content and the words,

Only the melody of the prayer.

While my eyes I close, I see again

Reminisces from my childhood

The yellow grayish glow of candle light,

Sad movements of arms and beards,

I hear a cry, wailing

An immense plea for mercy, a miracle ...

Whipping of the chest, clasping hands —

The glory of old books,

Fear of verdicts unknown and dark.

That night I'll never tear off my heart,

A menacing mysterious night,

And the grieved prayer Kol Nidre —

In the poem "Telephone, " Szlengel complains that no one

is left whom he can call in the Polish side of the city. In his last poems,

which he wrote when he was working in a broom workshop, Szlengel records

the decline of the ghetto and its final days. One such poem is "The Little Station:

Treblinka"

(translation by Yala Korwin):

On the Tluszcz-Warsaw line,

from the Warsaw-East station,

you leave by rail

and ride straight on …

The journey lasts, sometimes

five hours & 45 minutes,

but sometimes it lasts

a lifetime until death.

The station is tiny.

Three fir trees grow there.

The sign is ordinary:

it’s the Treblinka station.

No cashier’s window,

No porter in view,

No return tickets,

Not even for a million.

There, no one is waiting,

no one waves a kerchief,

and only silence hovers,

deaf emptiness greets you.

Silent the flagpole,

silent the fir trees,

silent the black sign:

it’s the Treblinka station.

Only an old poster

with fading letters

advises:

“Cook with gas.”

Szlengel was

apparently a ghetto policeman for a time, but he resigned, since he was

incapable of taking part in the roundups of ghetto inhabitants conducted by the

ghetto police during the deportations. Even in the final stages of that period,

Szlengel continued to recite his poems before small groups in clandestine

gatherings. In poems like "Five

Minutes to Twelve," Szlengel bids farewell to life, expresses his admiration for those offering resistance

with weapons in their hands, and calls for revenge:

Hear, O God of the Germans,

the Jews praying amid the barbarians,

an iron rod or a grenade in their hands.

Give us, O God, a bloody fight

and let us die a swift death!

Szlengel took part in the September of 1939 campaign against the German

invaders. The only Jewish writer who was still alive in the ghetto, he became

its chronicler. According to surviving evidence, Szlengel was a close friend of Janusz

Korczak.

Szlengel was killed in April 1943. He is known to have been in a bunker during the Warsaw

ghetto uprising, but the circumstances and the exact date of his death are

not known.

The Nazis destroyed the Jewish people and their literary works with equal

fanatical zeal.

Therefore, not much remains of Szlengel’s output. Only part of his poetry and prose writings

has been preserved. A

collection of his writings in Polish was published under the title Co

Czytalem Umarlym (What I Read to The Dead). This slender volume was published in 1977 by Warsaw Publishing

Institute. It begins with an introductory essay of the same title, followed by three one-page

essays, and around forty poems. The introductory essay is a

heart-wrenching account of the ghetto experience. It ends thus:

Do Read it.

This is our history.

This is what I read to the dead …

To read the entire essay, click here.

Our sincere thanks to Yala Korwin for the following translations of full-lengths poems

by Wladyslaw Szlengel:

New Holiday

Jews must have holidays,

Jews must remember

what Passover and what Purim mean;

that hamantash is because of Haman,

matzo because of Egypt,

colorful flags because of Torah;

lulav and sukkah and Hanukkah candles

remind of a deed, a miracle, a period.

This horrible war, that rends the Jews asunder,

to lumps, to tatters, to quarters, will pass.

Jews will survive.

One morning they will somehow resurface

and transmit greetings from Death.

Jews must have holidays,

Jews must remember

that miracle saved them again.

New holiday, similar to Sukkot,

though no booths, but cellars and garrets.

On Deliverance Day all will descend

to creep-holes, dark hiding places.

There, they will feast on prayers,

their hearts will fill with joy and with faith.

Spade, pickaxe, and sledgehammer

will become symbols of cult.

They will fast, as in shelters,

the old one will weep and the young listen

how it was when an Action…

how it was when a blockade…

The old one will recount

how they lived in their hovels

without air and for months…

In pitch dark they waited and waited

for the first breeze of wind,

for freedom, for sun…

The old ones will assent and applaud.

The young ones will scoff, saying

that the old grandpa embroiders.

…let him tell what he wants, but

it must be enlarged as the story

of the Red Sea and Moses.

They will leave their hideouts at dusk

to where all is peace and calm,

to the world prettier, better, and new.

In the safety of light, for the holiday dinner

they will serve swastikas with honey.

Published in Jewish Currents

Two Gentlemen in the Snow

Snow is falling, angry, pervasive,

trimming my collar with white wool.

We’re together in the empty street,

a Jewish slave-worker and a soldier.

I am homeless, and so are you.

Time’s boulder is crushing our lives.

So much divides us … just think of it …

but now the snow unites us.

Because of you I can’t budge.

You too — you have no choice.

Which one of us is holding whom?

It’s a third one who holds us both.

Your uniform is dashing, I admit.

I wouldn’t dare compare with you,

though the snow can’t tell us apart

the Jew and the handsome soldier.

Snow falls equally on me and on you.

It sheds so much white peace …

We both stare through the white veil

at the faraway light in the dusk.

Look, what am I up to? What are you up to?

What for? And who needs it?

Listen, my buddy, it snows and snows,

let’s split, and let’s go home.

Translation by Yala Korwin

Leave Me Alone

Stop, my friend,

if you intend to tell me

what my lot will be.

Leave me alone.

I don’t want to know,

I’m not curious!

Don’t bring me news

from underground papers,

and especially,

do not bring me such

from the men made of rubber,

wearing slippery coats.

Not from those who know,

from those who perceive,

not from those who heard

what they say in the workshop.

Don’t give me dates,

don’t whisper in asides,

I ’m not curious,

leave me alone!

What are you after?

What are you deploring?

What do you wish

still to achieve, to add?

Your zest for life

is not yet weakened?

Are you afraid that

they’ll send us to the devil?

Who are you? A Jew.

10 million Jews

drink whisky every day

and lick ice cream sodas

in the USA.

They drink grapefruit juice

before lunch, for breakfast.

You’re sorry for Jews?

They’ll last!

Not the frightened Jews,

not the sick, shivery Jews,

but the stadium Jews,

the singing Jews —

Leave me alone,

stop the pointless whispers.

This one — an optimist,

the other one — a skeptic.

Why the arguments?

Whom do we mean?

Lies — gentlemen —

keep your heads up.

Thomas Mann is writing another novel;

Chaplin is maneuvering, will be first again;

Tuwim [*] in his solitude, in Rio,

prepares a volume of poems;

Huberman is tuning his fiddle,

and with disdainfully puffed up lips,

is practicing a sonatina

non troppo and largo;

Einstein, in safety,

is silently mulling over

his theory of relativity.

Feuchtwanger, yes — in his Jewish heart

he shares our concerns,

but he will survive, gentlemen,

and will have The Jewish War

republished.

Lopek Krukowski [**] — Mlinczyk’s cousin,

is in the USA.

Just think about it, gentlemen — in short: Wells

and I ———————————

Who are you sorry for?

The 100 Jewish militiamen?

The fellows of the Council?

What kind of brains they have?

Nothing to regret.

Al Capone is alive,

and will replace them.

Think about it for a while,

and realize

what the world will lose,

and what it will gain.

You are wasting your nights,

sucking on your dry tongue,

searching in the columns

for some new hope.

Rumpling in your hand

yet another paper,

you ruminate, like a cow,

the news bulletins.

Just think for a while:

at this same hour,

Tolek Slonimski [***] is sitting in London.

Why do you worry about

What is happening

on the eastern front,

Algiers and Tunisia,

Toulon — Morocco —

all this I have —

you know where.

I find my comfort

in the genius saved.

Walt Disney’s films

“aere perennius.”

Don’t report anything,

don’t grab my sleeve,

whisper into my ear.

Do not read me that

on the first of the …

again Treblinka.

Vodka is good,

and girls are warm.

If your life now seems

too short to you,

come to me, my friend,

take me out for a vodka.

And bring your wife,

or someone else’s.

Let our glasses double

and even triple.

I will offer you

a bulletin, splendid,

all interwoven

with rimes and rhythms.

Let us drink

To Julian Tuwim.

It’s good that in Rio …

he will endure.

Let’s drink to Wells and to Lopek,

then leave me alone.

That’s it.

[*] Julian Tuwim was a Jew and a famous Polish poet.

[**] Lopek Krukowski was a Jew and a famous Warsaw actor and entertainer.

[***] Tolek Slonimski was a famous Polish–Jewish poet.

Translation by Yala Korwin

Christmas Legends

1. Jesus in Krupp's Factory

In the factory of Krupp & Co.,

among jumbles of iron and steel,

in the plant’s blazing hall,

on Christmas Eve, a child was found

near the bullets and bombs.

In Essen’s cradle of death,

those on the evening shift

discovered in a corner

a tiny creature, forgotten or lost.

The first star appeared,

just as in Bethlehem.

Its glow strayed in a tangle

of bombs, bullets, grenades.

And the child was lying

on the heap of grimy clothes,

and everyone wondered …

Someone whispered: “like Jesus …”

Awe took hold of the flock,

and shivers — as in a hot spell.

All production stopped

for a while.

Silence as huge as a bomb

hung over their heads.

All the chimneys hushed,

all gears, bellows, and mills,

motors, foundries, and forges.

The news of the miracle,

like a strange manifesto,

struck people with fright

Crowds gathered in the hall,

the child saw the people,

and they beheld the marvel.

They implored mercy,

genuflected, beat their breasts,

and cried …

Suddenly news arrived

and reached the human throng.

Toward Essen, toward Krupp’s factory,

three kings were approaching.

Christmas, twilight,

the star’s silvery brightness,

and the kings on their way ...

A miracle, as in Bethlehem.

The dense crowd staggered

like waves against a ridge.

The central loudspeaker

suddenly broke the silence.

The three kings were coming,

according to the speaker,

to the death-making cradle,

for they needed wares.

All the shifts back to work!

The Holiday postponed!

The kings needed bombs,

mines, cartridges, and guns.

The crowd moved swiftly

to the halls, the huts, and the bombs.

All the shifts were at work

at Krupp & Co.

the tapes of steel crackled,

flames of fire rose,

the heat of blood …

Jesus, at the plant of Krupp &Co,

was forgotten.

2. Miracle in the Trenches

Fearful Europe was waiting,

what are those in the trenches going to do? …

All those in the trenches

had tired feet, weary bones, eyes, and blood.

They had stopped counting offensives,

stopped counting days…

The general staff was drawing red lines,

shouting into the field telephones,

while someone bellowed into a broken handset.

Attention! All is ready …

In the

trenches — stooped backs,

all watches —

fearfully ticking,

something

flashed at the turn in the road,

tension grew

in the lines.

Veins swelled in all temples,

maps were red hot in palms,

eyes blinked with fury,

pulses quivered and throbbed,

and blood was impatient

for the final outcry: ”Hurrah!” …

A watch

revealed

hopelessness

and gloom,

in the blink

of a flashlight

disclosed the

time was ripe ...

The attack — soon. Soon they’ll set out

with bayonets, move forward,

soon both enemy lines

will leap toward each other,

sink their teeth into each other,

engage, pry edges into furrows,

eyes will go blind with blood.

Soon butt-ends, blades, and fingers

will crunch into each other,

soon two human waves

will clash in a dark battle.

One army is ready,

the other — still waiting

for the sign.

Human lines — two sides.

Close to nightfall now.

Look — a star shone forth —

for it was Christmas Eve.

Hard fingers were on triggers,

nerves — greyhounds loosed,

hearts — crash and pursuit,

Eyes — bloodshot circles —

Let them scream! Let them go!

Human dogs running forward

toward smiting and pricking,

bloody sowing and thrashing …

Trrrr — the telephone signal,

a shot drove them from their trenches.

The signal imbedded in their hearts,

they set out toward death …

Both foes —

running, running,

for a meeting

mid-way.

All rushing

and burning,

Palms on

butt-ends and triggers,

but on that

Christmas Eve

a miracle

occurred on the front.

When they were mid-way,

the human dogs — human foes —

stopped all of a sudden.

Their thrust restrained by someone,

they looked and contemplated …

Someone dropped the gun from his hand …

When they reached each other,

with the last of their initial drive

they broke, with each other,

Christmas wafers [*] rather than lives.

They shook each other’s hands,

cried in each other’s arms,

spoke, like brothers or sons,

of each other’s homes.

A call came from the general staff:

Again we broke in with a wedge …

[*] The Christmas wafer is a Polish tradition.

Translation by Yala Korwin

To read more English translations of several of Szlengel's poems, click here

and here and here.

Sources:

"Encyclopedia of the Holocaust"

©1990 Macmillan Publishing Company

New York, NY 10022

Yala Korwin

Museum of Tolerance

We Remember

Poetry on the Shoah

The HyperTexts