The HyperTexts

The Lynching of James Cameron, Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith

The excerpted article below, taken from an oral presentation by James Cameron

at Indiana University, was published Friday, January 12, 2001 by IDS News.

Cameron's story has been reported or portrayed by Nightline, PBS, HBO, Ebony, Village Voice,

Newsweek, The Washington Post, in the book Lynching in the

Heartland by James Madison, and in the book The God Moment by Alan D.

Wright. There are different slants on what happened, which is understandable due

to the milling confusion of an enraged mob that seems to have quite possibly

numbered in the thousands. But the accounts I have read all seem to agree on the

main facts. The interpretation of The Voice and where it originated is "up in

the air." Comments and clarifications not in the original IDS article appear in

brackets below; excerpts from other attributed accounts appear in italics. Minor

corrections of punctuation, the spelling of "Shipp," and the

elimination of repetitious and redundant words and phrases (particularly of "he

said" seemingly ad infinitum) have been made to the IDS account.

—

Michael R. Burch

... Cameron's story began in 1930 ...

"Hate is a disease, and in 1930 I became sick with

hatred."

Cameron [then 16] was with his two friends, Abe [Abram] Smith and Tommy

[Thomas] Shipp, when his friends decided to rob someone they saw sitting in a

parked car. Shipp gave Cameron a gun, and Cameron opened the door

to the car. What he saw stunned him.

"That white man [Claude Deeter], in that car, was my friend. I shined his shoes, sometimes, and he always asked me about

my family."

Cameron gave the gun back to his friends and ran. He heard gunshots as he ran, but he didn't stop until he reached his home. Police

later came to take him away. A white man was dead and his white girlfriend [Mary

Ball] had been raped, they said.

After questioning at the station, the police took Cameron to jail.

"I will never forget my mother pleading and crying for them to take her

instead of me. That's just not something you

forget."

The three boys were put into separate cells until an angry mob [Wright and Madison

both mention

"thousands"], led by the Ku Klux Klan, came to get them, one by one.

He was third, and as he was taken to the tree where his friends had met their

deaths, Cameron begged people he knew for help, but they said nothing.

Madison says: "[The lynch mob] actually did break into that jail through several steel doors and bars.

Then they removed the prisoners one by one: first Shipp, who was taken to the

courthouse square and hanged from the bars of one of the jailhouse windows; then

Smith, who was lynched by a rope thrown over the branch of a maple tree."

The ABC News/Nightline account quotes Cameron as saying, "When they

got me down to street level, the uniformed police was helping the mobster

members, who had their robes and open-face hoods on. They were helping … to

clear a path from the jail up to the courthouse square, which was just a half a

block away. And one young lady was standing on the hood of an automobile that

was parked on the jail lawn, and she was jumping up and down saying, 'Kill all

the niggers! Kill all the niggers! Kill all the niggers!'"

Finally, Cameron stood with death on both sides of him as they put

the noose around his neck.

"At that moment I said 'Lord forgive me my sins' and I felt this calm

wash over me. It had been a miracle up until that

point that I had not been beaten. Then came the next miracle."

I believe there may be a transposition error in the IDS account above, as

all the other accounts I have read have Cameron being beaten. Perhaps he said

something like, "It had been a miracle up until that point that I had not

been beaten to death." Or perhaps "beaten unconscious." This

would make sense because some accounts have Shipp and Smith being killed and

mutilated before they were hung. Also, in Sharon Cohen's AP account (at the

bottom of this page) Cameron says "The miracle is I didn't go

unconscious." -- MRB

As Cameron stood there waiting for his death, he heard a voice.

"[It said:] 'Take this boy back. He had nothing to do with this,'"

Cameron said. "I heard this voice, but no one else did. Nevertheless, the

crowd grew quiet and they released me."

...

Wright reports Cameron saying at eighty-six, "It was a voice from

heaven. It was a miracle ... God saved me for [what] I'm doing today."

Other accounts describe the voice as "an angelic voice" and as a

"sweet, undefiled, and distinct voice, unlike any he had ever heard."

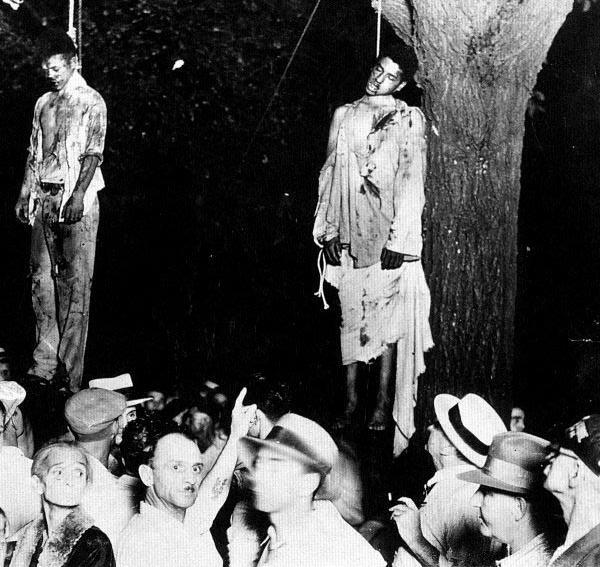

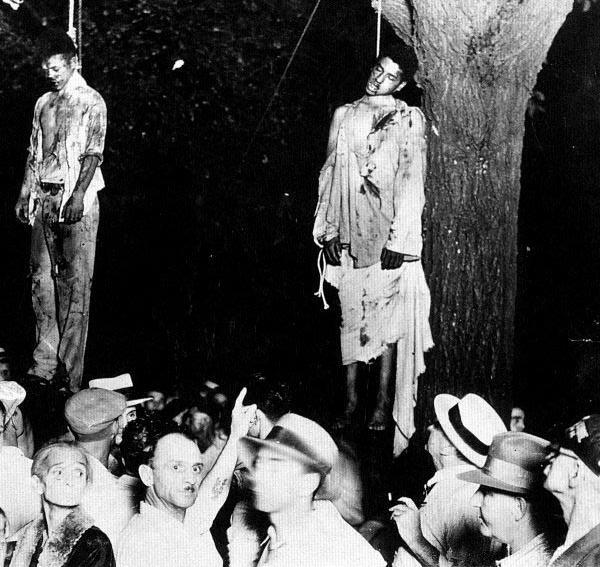

Seeing the picture below, it's hard to imagine an ordinary voice that could

calm this mob. -- MRB

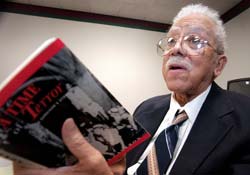

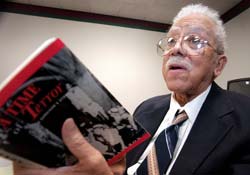

The following account has been excerpted from James Cameron's book A Time

of Terror: Thousands of Indianans carrying picks, bats, ax handles, crowbars,

torches, and firearms attacked the Grant County Courthouse, determined to 'get

those goddamn Niggers.' A barrage of rocks shattered the jailhouse windows,

sending dozens of frantic inmates in search of cover ... The door was ripped

from the wall, and a mob of fifty men beat Thomas Shipp senseless and dragged

him into the street ...The dead Shipp was dragged with a rope up to the window

bars of the second victim, Abram Smith. For twenty minutes, citizens pushed and

shoved for a closer look at the ‘dead nigger.’ By the time Abe Smith was

hauled out he was equally mutilated. ‘Those who were not close enough to hit

him threw rocks and bricks. Somebody rammed a crowbar through his chest several

times in great satisfaction.’ Smith was dead by the time the mob dragged him

‘like a horse‘ to the courthouse square and hung him from a tree. The

lynchers posed for photos under the limb that held the bodies of the two dead

men. Then the mob headed back for James Cameron and ‘mauled him all the way to

the courthouse square,’ shoving and kicking him to the tree, where the

lynchers put a hanging rope around his neck. Cameron credited an unidentified

woman's voice with silencing the mob and opening a path for his retreat to the

county jail and, ultimately, for saving his life ... After souvenir hunters

divvied up the bloodied pants of Abram Smith, his naked lower body was clothed

in a Klansman's robe — not unlike the loincloth in traditional depictions of

Christ on the cross. Lawrence Beitler, a studio photographer, took this photo.

For ten days and nights he printed thousands of copies, which sold for fifty

cents apiece.

According to PBS, Mary Ball later testified that Cameron had fled before

the shootings and that she had not been raped. Cameron was released after

serving around four years in prison, and he received a pardon in 1993 from

Indiana Governor Evan Bayh.

From the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee web site: After

surviving the incident, Cameron went on to become a self-taught historian and

student of civil rights and democracy. During the 1940s he founded four chapters

of the NAACP in Indiana and served the anti-discrimination cause in a number of

other positions. Cameron moved to Milwaukee in the 1950s, and worked with Father

James Groppi and others to end housing discrimination in the city. He continued

his educational efforts, authoring more than 240 articles and pamphlets and

speaking before a variety of groups in the U.S. and Europe. His efforts

culminated in 1988 with the founding of the Black Holocaust Museum. A pioneering

institution honoring the contributions and sacrifices of America's black

citizens, it has gained national and international recognition for the integrity

of the concept that anchors it, the soundness of the history it chronicles, the

range and uniqueness of the artifacts that it houses, and the value of its rich

learning environment.

The video "Third Man Alive: Story of Dr. James Cameron" reports

that Cameron is the only still-living survivor of a lynching.

Madison says, “At times Cameron seemed like an Old Testament prophet,

warning of the sins of racism.”

From Profiles in Black, here's a Cameron prophesy: "The Klan

should be stamped out, and the people should be the ones to stamp it out."

We couldn't agree more!

America’s Black

Holocaust Museum, Inc.

2233 N. Fourth Street

Milwaukee, Wisconsin USA 53212

Phone: 414-264-2500

Tax-deductible donations

can be sent, by check or money order, to:

America's Black Holocaust Museum, Inc.

c/o James Cameron

North Milwaukee State Bank

5630 West Fond du Lac Avenue

Milwaukee, Wisconsin USA 53216

Here's a another account, by AP's Sharon Cohen, which appeared in the

Standard-Times, February 17, 2003:

He remembers every detail about that long-ago night: the pearl-white glow of

the moon, the roar of the frenzied mob, the fists and clubs beating him -- then

the rough hands forcing his head into a noose.

And, of course, he remembers the rope. It left a burn mark on his neck.

He is an old man now, a great-grandfather with a cane and a cap of frosty

silver hair, and it has been nearly 75 years since two of his friends were

lynched one horrible August night -- and he was supposed to be next.

James Cameron of Milwaukee, Wisc., turned his near-death experience into his

life's work, telling his story of Aug. 7, 1930, hundreds of times over the years

and creating America's Black Holocaust Museum -- dedicated to the suffering

blacks have endured throughout the nation's history.

Now, Cameron, about to turn 89 and frail from heart surgery and cancer, is

determined to keep the flame burning and make sure his small, struggling

15-year-old museum stays open after he is gone.

"It's the most important thing in the world to me to carry on this

fight, to explain the history that's been hidden ... from black people," he

says.

"I wonder if God saved me for this mission," he says. He

pauses, then answers his own question. "It had to be. And I thank him for

that."

When Cameron talks about the night he was almost killed, his words flow like

those of an actor with a keen sense for the dramatic pause, the telling detail,

the precise moment to raise or lower his raspy voice.

Always, the memory brings tears to his eyes.

Cameron, then 16 and living in Marion, Ind., had finished playing horseshoes

and had accepted a ride from his friend, Thomas Shipp. Soon they picked up Abe

Smith.

They coasted along in the 1926 Ford roadster, he says, when one of the other

teens suggested holding up someone to get money. Cameron says he told them he

wasn't interested but they all drove to a lover's lane.

One of his companions, he says, handed him a .38-caliber revolver and

calling him by his nickname, said: "Apples (Cameron's mother had an apple

orchard), you take the gun and hold the people up."

Cameron approached a car and pointed the gun at a man -- who was with a woman

-- but realized he was one of his regular shoeshine customers. So, he says, he

gave the gun to Shipp, told him he wouldn't rob anyone, then ran down the road.

A few moments later, he heard gunshots.

The man in the car had been shot to death. Rumors spread that the woman was

raped. Both were white.

The three black teens were quickly rounded up and taken to jail, where

thousands of people, including women and children, gathered with gas cans, iron

bars and sledgehammers, crashing through bricks and pounding down the door. The

mob rushed past law enforcement officers to grab the men.

Marion actually had fairly good race relations, for the time, says James

Madison, an Indiana University history professor who wrote about the incident in

"A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America." He says the

town had an NAACP branch and two black police officers.

None of that mattered that night.

Shipp and Smith were brutally beaten, then lynched on a tree in the

courthouse square.

Cameron was next.

"They began to chant for me like a football player, 'We want Cameron, we

want Cameron,'" he recalls, clasping his hands tight. "I could feel

the blood in my body just freezing up."

Cameron, who says he was beaten into signing a false confession, was hit in

the head with a pick handle, pummeled with fists, clubs and rocks, bitten and

spat on as the mob dragged him out of the jail, shouting racial slurs.

"The miracle is I didn't go unconscious," he says.

They pulled him toward the tree, where he saw the dangling, bloody bodies of

his friends.

"They put the rope around my neck and threw it over the limb,"

Cameron says. "They were getting ready to hang me up when I said, 'Lord,

have mercy, forgive me my sins.' My mother always told us children, before you

do anything, always pray."

So he prayed. "Then," he says, "I gave up hope."

Then suddenly, he claims, came a heavenly voice with an order: "Take

this boy back. He had nothing to with any raping or killing."

The crowd then parted, he says, as he stumbled back into the jail.

Cameron has asked others there that night, but no one heard that voice.

But there apparently was a protest.

One man stood atop a car and shouted out that Cameron was innocent and should be

let go, according to documents unearthed by Madison, who said a few others also

tried to calm the crowd.

The lynching scene was captured in a photo -- reproduced and sold for 50 cents

-- that became an enduring symbol of racial terror in America. It shows a

milling crowd, people smiling or staring calmly into the camera, women in summer

dresses, men in fedoras and ties, one pointing up to the mutilated bodies.

Two men were charged with inciting the mob, but they were acquitted, according

to Madison.

Cameron was convicted of being an accessory before the fact to voluntary

manslaughter. He spent four years in prison, was free at age 21, and attended

technical high school and college.

He and his wife, Virginia, wed nearly 65 years, raised five children, and

Cameron supported them as a truck driver, laundry man, record store owner,

waiter, junk man and maintenance engineer.

He was a strict father, instilling pride in his children, says his 59-year-old

son, Virgil, who recalls how the family resisted the segregation policies at

movie theaters in Indiana.

"We sat wherever we wanted," he says. "We were the Camerons. He

had that type of strength. He would not tolerate racism."

Cameron was always determined to tell his story. In 1946, he sent a letter to

his idol, poet-writer Langston Hughes, seeking advice. He received an answer

(framed on his museum wall) but no publisher.

Decades passed and in 1979, he and his wife visited Israel and Yad Vashem, the

Holocaust memorial, where he was moved by exhibits of Jewish persecution and the

inscription: "To remember is salvation. To forget is exile."

Turning to his wife, he said, "Honey, we need a museum like that in America

to show what happened to black people."

The big civil rights museums were still years away, and Cameron's interests were

in the horrors of slavery and lynching -- atrocities he felt were neglected by

white historians.

When he began soliciting help for his museum, he says, "People thought I

was crazy. They thought everything should be buried and not dug up."

He forged ahead and published his memoirs in 1982, mortgaging his house to print

5,000 copies of "A Time of Terror." The book was later reprinted by

Black Classic Press.

For his museum, Cameron visited the Library of Congress; he haunted rummage

sales and bought books, lynching photos and Ku Klux Klan robes and hoods.

In 1988, he opened his museum in a small storefront room, then six years later,

moved to an abandoned 12,000-square-foot gym the city of Milwaukee sold him for

$1.

About that time, he met a philanthropist, Daniel Bader, who offered a generous

check.

"He's somehow able to put you in his skin and let you see the world through

his eyes," says Bader, president of the Helen Bader Foundation, which

remains a financial supporter.

On a whim, Cameron says he wrote a letter to the governor of Indiana in 1991

seeking a pardon. Two years later, it was granted.

"It meant a hell of a lot to me," he says. "They forgave me for

what I had done and I forgave them what they had done to Abe and Tommy and

me."

A week later, Cameron, decked out in a black tuxedo, returned to Marion to

receive the key to the city which, an accompanying letter said, should serve to

"lock out any denial of the abuses of that ugly time."

The letter is displayed at the museum but another piece of Marion's past is

locked up for safekeeping -- a thumb-size hunk of yellow rope given to him

several years ago that was purported to have been used in the lynchings.

Over the years, Cameron's museum has featured the works of black photographers

and artifacts from the Henrietta Marie, a slave ship found off the Florida

coast.

But times have been tough and the museum operates on a shoestring budget, says

Jessie Leonard, the interim director. She says she's still looking for financing

for a permanent exhibit on Cameron's life -- from his days as a young man

helping to form three NAACP chapters to his protest at a Klan rally a few months

ago, in a wheelchair.

Leonard calls Cameron "a quiet soldier" but "not so quiet he

cannot be heard."

And he vows to continue talking -- and protesting -- as long as he can.

"Something inside me," he says, "just keeps urging me on."

If you're a student, teacher, educator, peace activist or just someone who cares and wants to help, please

read

How Can We

End Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide Forever? and do what you can to make the world a safer, happier

place for children of all races and creeds.

If you're interested in other accounts of angelic intervention, you may be

interested in these Mysterious Ways pages:

No Hell in the Bible

A

Direct Experience with Universal Love

Two Tales of

the Night Sky

Genie-Angels

Darkness

Michael,

Wonderful and Glorious

The Poisonous Tomato

Mysterious Ways Index

The HyperTexts

Note: If you like this article, you are free to cut and paste it, to print it out, and to distribute it

freely, however you see fit. I do ask that you abide by the following: (1)

Please be sure to accredit the authorship of the article correctly and to cite

www.thehypertexts.com as the original publisher. (2) Please be

sure that this note is attached to the article whenever and wherever the article

is printed out, forwarded, re-published, or otherwise distributed. My sincere

thanks! — Michael R. Burch, editor, The HyperTexts