The HyperTexts

WILLIAM BLAKE: His Most Famous Poems and Artworks

William Blake wrote some of the most famous poems in the English

language, and some best poems, period. For example, Blake's "The Tyger" is the most-anthologized English poem

and may be the most famous poem of all time.

Other poems by Blake remain very popular with readers and admired by critics.

Blake is also a famous artist and engraver. This page

explores the visionary poetry and visual art of one of England's most gifted

(and most eccentric) geniuses.

compiled by Michael R. Burch

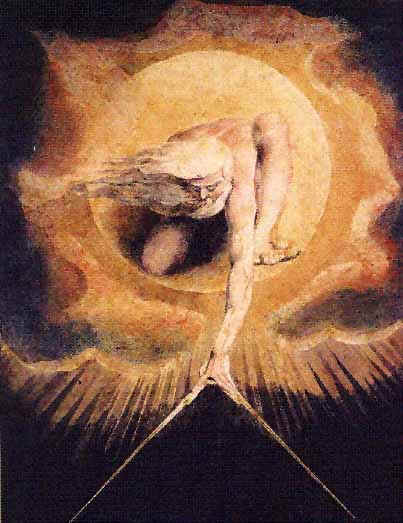

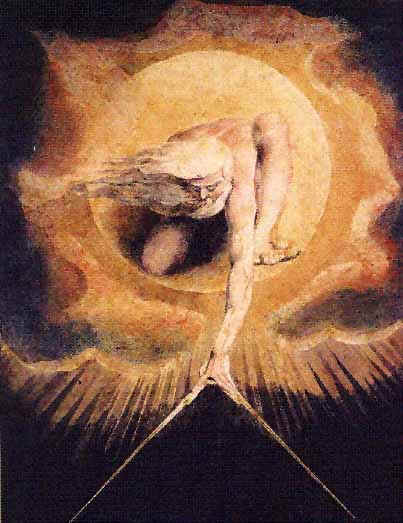

William Blake's "Ancient of Days"

These are the ten most famous poems by William Blake, not necessarily his ten

best poems, although all ten are excellent in my opinion ...

(#10) "The Chimney Sweeper"

(#9) "The Garden of Love"

(#8) "The Poison Tree"

(#7) "The Little Black Boy"

(#6) "Holy Thursday"

(#5) "The Lamb"

(#4) "London"

(#3) "Jerusalem" aka "And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time"

(#2) "The Sick Rose"

(#1) "The Tyger"

Honorable Mention: "Cradle Song" (my personal favorite although not as well

known as the poems above), "The Divine Image," "Ah! Sunflower," "Auguries of

Innocence" aka "To see a World in a Grain of Sand," "Never Seek to Tell Thy

Love," "How Sweet I Roam'd," "Infant Joy," "Infant Sorrow," "The Clod and the

Pebble," "The Echoing Green," "The Blossom," "Milton: a Poem"

Please keep in mind that some of Blake's poems have two versions: one in

Songs of Innocence and one in Songs of Experience. For instance,

there are two versions of Blake's chimney sweeper poems and his "Holy Thursday."

I am considering these poems together in my ranking above.

William Blake may have been, in one of the ultimate ironies, both England's

greatest heretic and its greatest visionary prophet. Together with Dante and

Milton, Blake completes a Trinity of great Christian poets, despite the fact

that none of them were Christians in the orthodox sense (Dante claimed to be

saved by his lover Beatrice and the pagan poet Virgil; Milton rather, than

justifying the ways of God to man, made him seem like an unjust tyrant while

turning Lucifer, Adam and Eve into Romantic heroes for the ages; Blake denied

the need for anyone to save him, least of all the biblical god, whom he called

"Nobodaddy").

The Sick Rose

by William Blake

O Rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm

That flies in the night

In the howling storm

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy,

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

According to Blake, human society and its institutions were sick, and the cure

required a combination of revelation, imagination, right thinking, compassion,

fierce tenacity and love. He believed the black-robed priests of religion had

nailed a "thou shalt not" sign over the garden of earthly delights, robbing

adults of pleasure and children of hope. He vowed to not let his pen rest in his

hand until he had won the "Mental Fight" to transform the dreary London of his

day into a new Jerusalem. Today, as we witness the suffering inflicted on

innocent children all around the globe in the name of state, industry and

religion, it behooves us to consider joining that Mental Fight on the side of

Blake and his Rebel Angels.

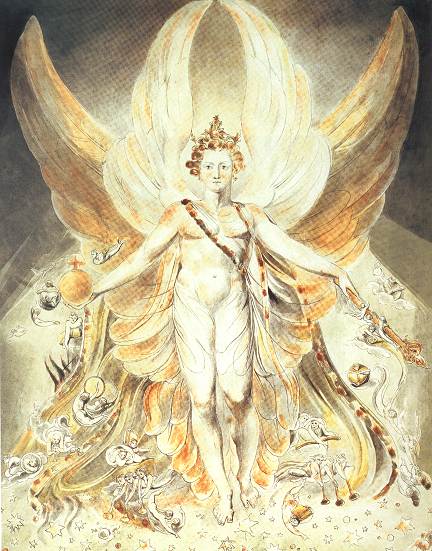

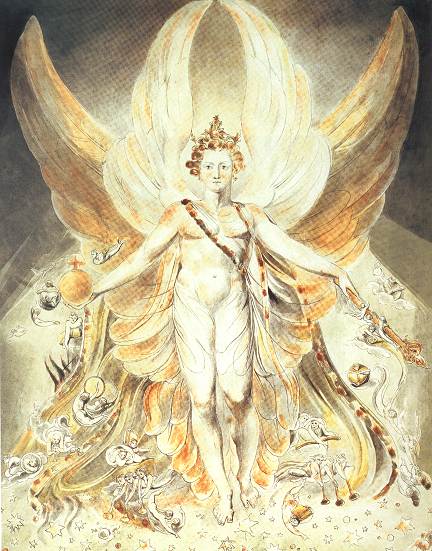

William Blake's "Angel of Revelation"

![[Blake Print - Angels Hovering Over the Body of Jesus in the Sepulchre]](images/William%20Blake%20Angels%20Hovering%20Over%20the%20Body%20of%20Jesus%20Christ.jpg)

William Blake's "Angels Hovering Over the Body of Jesus Christ in the Sepulcher"

![[Blake Print - Jacob's Ladder]](images/William%20Blake%20Jacobs%20Ladder.jpg)

William Blake's "Jacob's Ladder"

![[Blake Print - Hecate]](images/William%20Blake%20Hecate.jpg)

William Blake's "Hecate"

In my opinion William Blake (1757-1827) is the most important poet/artist of all time. Why? Because

he helped change the world and in changing the world he saved many innocent children

from lives of drudgery and misery terminated by premature deaths. While he wrote many

wonderful poems and was also a talented painter, printer and engraver, what

makes Blake the most important of poets and artists is the change his work wrought in human

hearts, minds and consciences. No great poet ever wrote more compassionately about children. For instance, take this poem of Blake's, one of

the loveliest lullabies in the English language:

Cradle Song

Sleep, sleep, beauty bright,

Dreaming in the joys of night;

Sleep, sleep; in thy sleep

Little sorrows sit and weep.

Sweet babe, in thy face

Soft desires I can trace,

Secret joys and secret smiles,

Little pretty infant wiles.

As thy softest limbs I feel

Smiles as of the morning steal

O'er thy cheek, and o'er thy breast

Where thy little heart doth rest.

O the cunning wiles that creep

In thy little heart asleep!

When thy little heart doth wake,

Then the dreadful night shall break.

William Blake was a mystic: like Walt Whitman he displayed an affinity for all

life in his poetry ...

Ah! Sunflower

by William Blake

Ah! sunflower, weary of time,

Who countest the steps of the sun,

Seeking after that sweet golden clime

Where the traveller’s journey is done;

Where the youth pined away with desire,

And the pale virgin shrouded in snow,

Arise from their graves and aspire;

Where my sunflower wishes to go.

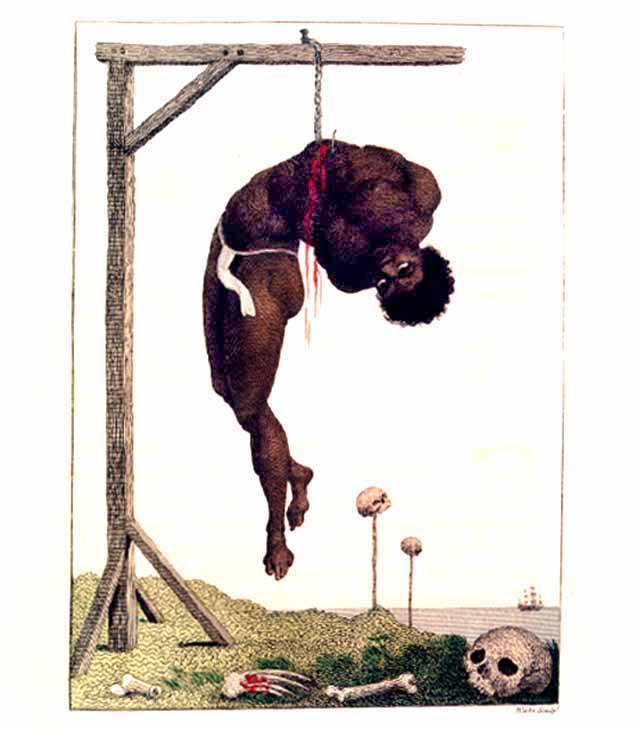

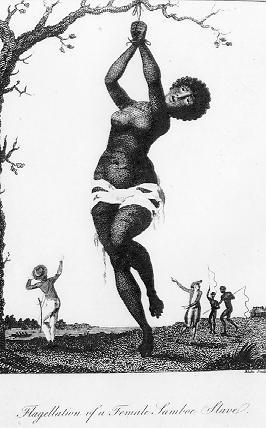

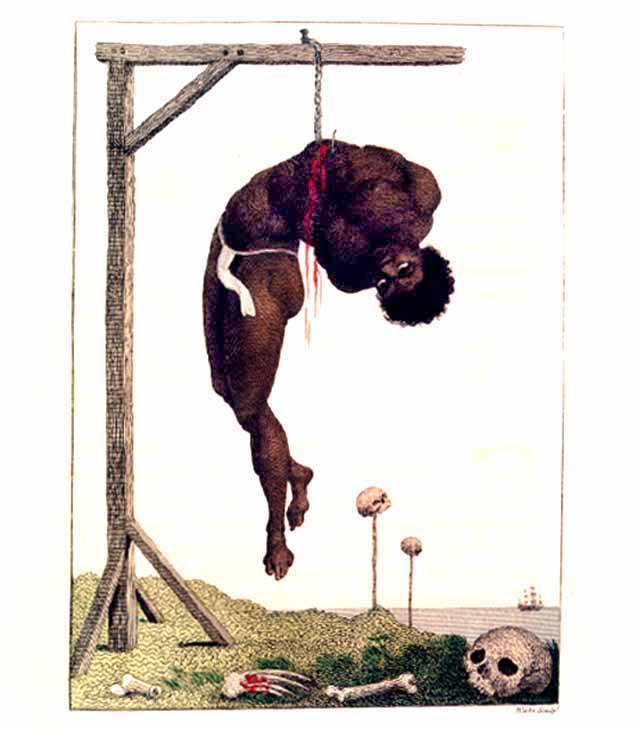

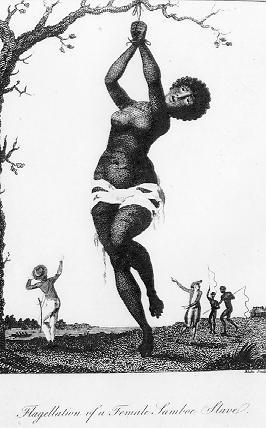

Blake was the first artist to graphically depict the horrors of slavery ... you

can see a slave ship departing in the background ...

William Blake's "A Negro Hung Alive"

Blake was at the forefront of the British abolitionist movement, not only in

opposing slavery, but also in advocating the equality of the races, as we shall see

in the following poem (the full poem follows the plates and is much easier to

read):

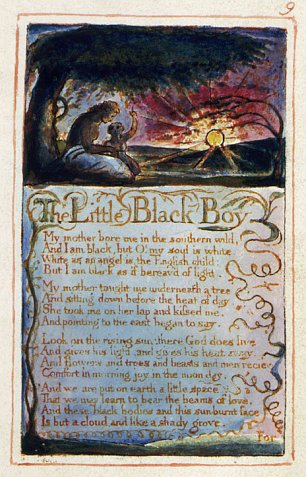

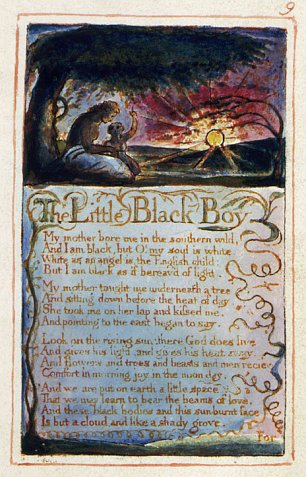

William Blake's "The Little Black Boy" (First Plate)

William Blake's "The Little Black Boy" (First Plate)

The Little Black Boy

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child,

But I am black, as if bereav'd of light.

My mother taught me underneath a tree,

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east, began to say:

Look on the rising sun: there God does live,

And gives his light, and gives his heat away;

And flowers and trees and beasts and men receive

Comfort in morning, joy in the noonday.

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love;

And these black bodies and this sunburnt face

Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove.

For when our souls have learn'd the heat to bear,

The cloud will vanish; we shall hear his voice,

Saying: "Come out from the grove, my love & care,

And round my golden tent like lambs rejoice.''

Thus did my mother say, and kissed me;

And thus I say to little English boy:

When I from black and he from white cloud free,

And round the tent of God like lambs we joy,

I'll shade him from the heat, till he can bear

To lean in joy upon our father's knee;

And then I'll stand and stroke his silver hair,

And be like him, and he will then love me.

Blake also spoke clearly and forthrightly for equality between the races in his

visual art. He depicted the horrors of racism and slavery more graphically than he did

any other horrors ...

William Blake's "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave"

... but he seemed to go beyond that to "connect" the suffering of slaves with

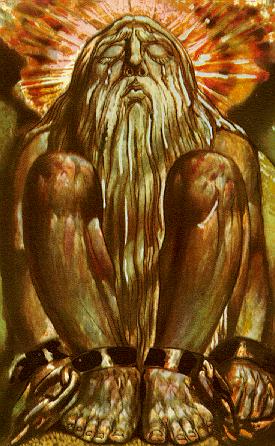

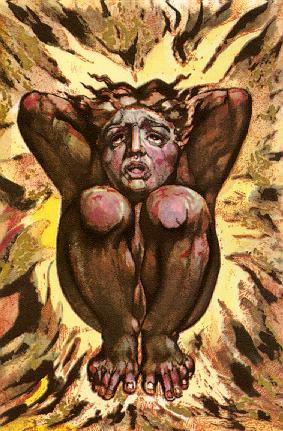

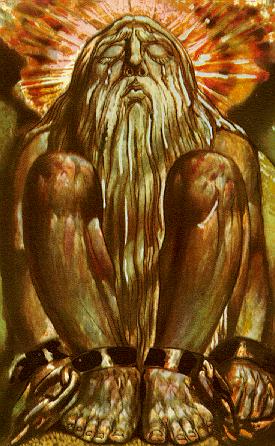

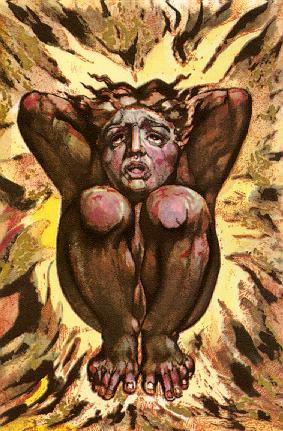

the lot of suffering mankind, even poets, symbolized in the second image below by Los ...

William Blake's "Urizen in Fetters, Tears streaming from His Eyes"

William Blake's "Los, Symbol of Poetic Genius, Consumed by Flames"

Blake and other early Romantic poets including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor

Coleridge and Robert Southey, opposed slavery. In 1796 John Gabriel Stedman, a

mercenary, published his memoirs of a five-year expedition against ex-slaves in

Surinam; his book included a number of engraved illustrations by Blake depicting

the horrifically cruel treatment of recaptured slaves. The first of these engravings has been "construed as an

explicit attack on the slave trade" because Blake depicted "the skulls of the

murdered slaves looking out over the sea to a slave ship in the distance while

the most recent victim of plantation cruelty swings on the gallows in the

foreground." These images were unique at that time for their graphic depiction of human suffering.

Stedman's book and Blake's illustrations became part of abolitionist literature.

According to the "William Blake Biography" the poet was a "prophet against empire" who opposed slavery

"over the course of his lifetime." Through his poetry and art "he was able both to counter pro-slavery propaganda

and to complicate typical abolitionist verse and sentiment with a profound and unique exploration of the effects

of enslavement and the varied processes of empire."

According to the same biography, Blake's Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793) "explores the psychologically

damaging effects of enslavement upon its victims and also caricatures the political debate over

abolition in Britain. The triangular relationship between Oothoon the female

slave, Bromion the slave-driver, and Theotormon the jealous but inhibited former

lover, depicts the sufferings of those subjugated by the trade itself and mimics

the position of the pro-slavery, vested-interest lobby and that of wavering

abolitionists [who opposed slavery in theory without strongly opposing its

actual practice] ..."

The biography concludes: "Blake was among the few British writers

who actively advocated slave rebellion and believed that it was at the edges of

empire that true revolutions would occur."

Only Michelangelo ranks with William Blake, among great artists who also wrote superior poetry,

in combined achievement. But Michelangelo didn't rock the civilized world to its

foundations the way Blake did, so Blake also gets my vote as the most important

artist of all time.

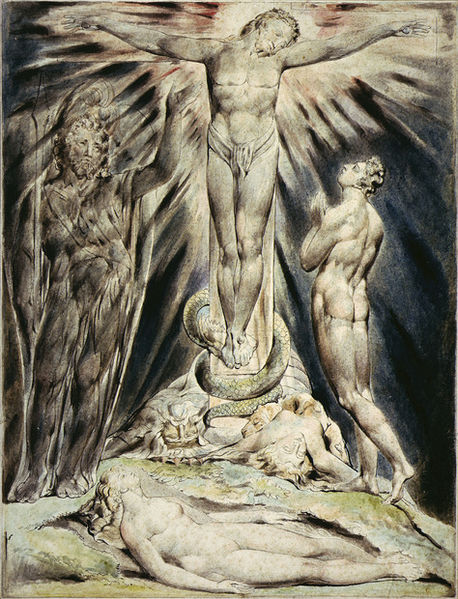

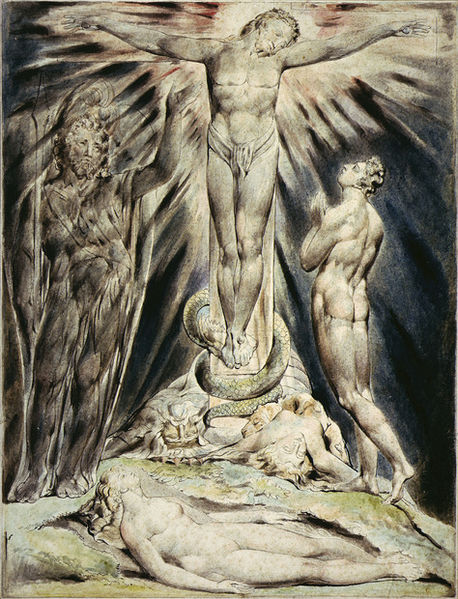

William Blake's "Michael Foretells the Crucifixion"

How, exactly, did Blake rock the foundations of the world? By being a social critic and reformer akin to the

Hebrew prophets. Here, for instance, is his bleak vision of the London of his day:

London

I wander thro' each charter'd street,

Near where the charter'd Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infant's cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forg'd manacles I hear.

How the Chimney-sweeper's cry

Every blackning Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldier's sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro' midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlot's curse

Blasts the new-born Infant's tear

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

Here, as in other of his poems, Blake reveals the schizophrenia of a society of

Bible-believing, church-going adults who inexplicably allowed children to work

as chimneysweeps: an always-dangerous, sometimes-deadly occupation. Today's

children of Gaza can no doubt sympathize with defenseless English children who

suffered and died in the shadows of those despicable churches. While Jews and

Christians raise hymns to God, and elect themselves the "Chosen Few,"

completely innocent Palestinian children live in abject fear and misery. Like

Blake, I find that appalling.

If you are a student, teacher, educator, peace

activist or just someone who cares and wants to help, please read

How Can We End Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide Forever?

and do what you can to make the world a safer, happier place for

children of all races and creeds.

Blake was also a fierce critic of

what Dwight D. Eisenhower would later call "the military-industrial complex." Blake

had a more evocative term for factories that churned out implements of war

and death: "Satanic mills." Blake is thus the forefather of virtually

every singer-songwriter who ever wrote a protest song. Before Blake, few poets

and minstrels had the nerve to criticize church and state. After Blake, many of

them would come to consider dissent a sacred task. Songwriters who followed in Blake's

footsteps as critics of the military-industrial complex include Woody Guthrie,

Peter Seeger, Bob Dylan, John

Lennon, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Jim Morrison, Marvin Gaye, Billy Joel and Bruce Springsteen.

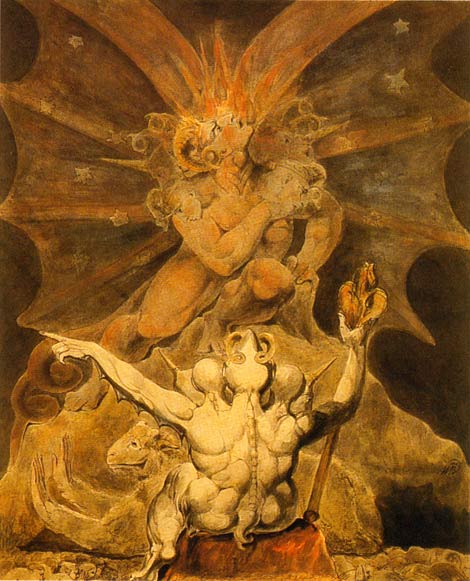

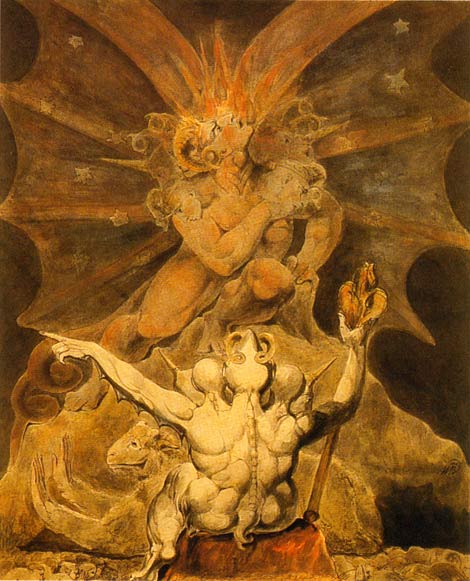

William Blake's "The Number of the Beast is 666"

How influential did Blake become? According to John Lennon's FBI files, when the

"fantastically nervous" Beatles met Bob Dylan for the first time and there was

an uncomfortable initial silence, broken by Lennon snarling an insult at Allen Ginsburg, the unperturbed

Beat poet plopped himself down in Lennon's

lap, looked up and asked him, "Have you ever read William Blake, young

man?" Lennon, in his best "Liverpudlian deadpan" replied, "Never heard of the

man." But his wife Cynthia chided him, "Oh, John, stop lying!" and that "broke the ice."

It's interesting that Blake was the first "connection" and "ice breaker" between Dylan, Lennon and

Ginsburg. Why did such super-hip modern dissident artists admire Blake? Probably because they were idealists longing for Utopia (or, at the

very least, for radical social change) and Blake had urged his readers to cast off the "mind-forged

manacles" of hidebound religious and political thinking, in order to

change the dreary London of his day into a Mecca he called Jerusalem:

Jerusalem

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England's mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England's pleasant pastures seen?

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic mills?

Bring me my bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire.

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England's green and pleasant land.

Please note that Blake said "till we have built

Jerusalem."

Blake's "Jerusalem" is based on the legend that Jesus once visited England as a

boy or young man. But what is most

surprising about the poem is Blake's activism. He didn't just mope and complain

about the problems he saw: he called for his spiritual and intellectual

weaponry, vowing not to let his "sword" (i.e., his pen) sleep in his hand

until London had become the new Jerusalem. The poem was later turned into a

stirring hymn (one of my mother's favorites):

William Blake's "Portrait of Milton"

William Blake's "Satan in Glory"

William Blake "The Song of Los"

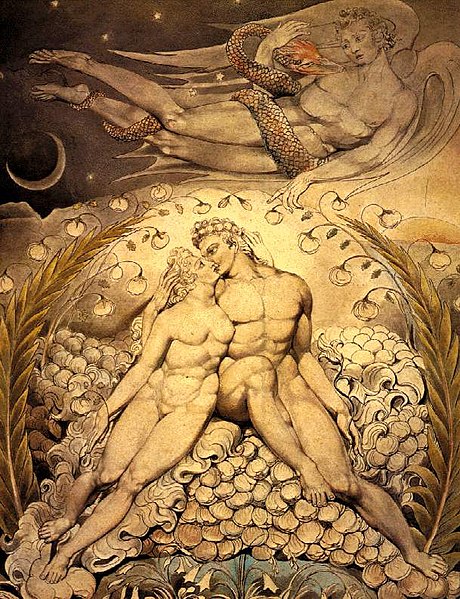

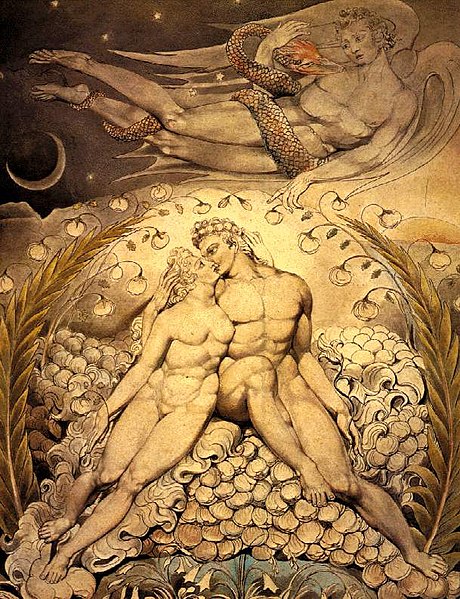

William Blake's "Sata Amor Adao Eva"

William Blake's "Eve Tempted by the Serpent"

From what I understand of Blake, he didn't subscribe to the idea that Jesus was

a "sacrifice." In the Laocoön engraving he wrote,

"Jesus and his Apostles and his Disciples were all Artists ... The Old and New

Testaments are the Great Code of Art. Art is the Tree of Life. God is Jesus."

When he says that God is Jesus, I take Blake to mean that Jesus is where

divinity and humanity intersect and become one. When he said of Jesus that "He

is the only God ... and so am I and so are you," Blake was agreeing with Muslim

Sufi mystics who claim to be one with God, and with Christian mystics who say

the same thing, and with the mystics and shamans of many other religions as

well. The best explanation I have heard of this common mystical belief is that

God is the great sea of unity and that each human being is like an individual

wave rising from that sea and collapsing back into it. While it seems unlikely

that anyone can "prove" this to be true, it is interesting that the idea recurs

over and over again around the globe and throughout time. So perhaps Blake was

correct to speak of "The Everlasting Gospel" and describe it as being unchanged

from greatest antiquity. For the mystic the Holy Trinity and a human family may

be one and the same: Father, Mother and Child. Due to the chauvinism of the

writers of the Bible, the female member of the Trinity (the Hebrew word SHEKHINA

is feminine) was virtually written out of existence, becoming the oddly but

perhaps aptly named "Holy Ghost." Blake also denied that Mary was a virgin,

which wasn't a problem for him because he considered sex to be good, not a

"sin."

When Blake criticized the orthodox Christian vision of Jesus, he did so with "an imagination and

excessiveness that has rarely been matched." Blake's Jesus was not a moralizing

preacher, philosopher or savior, but "the

very embodiment of the poetic" and a "supremely creative being above rigid

dogma, above harsh logic, above even morality. Jesus explodes from the pages of

Blake's poetry with a fierce apocalypticism far removed from the eminently

rational Enlightenment Jesus." Blake's Jesus "becomes more than just a thinker

or a moralizer, he becomes a symbol of being, of the vital and non-dualistic

relationship between divinity and humanity." These opening lines from "The

Everlasting Gospel" illustrate Blake's extreme distaste for what orthodoxy had

done to the reputation of Jesus Christ:

The Everlasting Gospel

THE VISION OF CHRIST that thou dost see

Is my vision’s greatest enemy.

Thine has a great hook nose like thine;

Mine has a snub nose like to mine.

Thine is the Friend of all Mankind;

Mine speaks in parables to the blind.

Thine loves the same world that mine hates;

Thy heaven doors are my hell gates.

Socrates taught what Meletus

Loath’d as a nation’s bitterest curse,

And Caiaphas was in his own mind

A benefactor to mankind.

Both read the Bible day and night,

But thou read’st black where I read white.

With Blake's imaginative reinterpretation of Milton, Satan, Jesus, the Bible and

Christianity, an English

"Romantic" movement began to form and soon expressed itself: primarily through poetry,

prose and art. England managed to avoid the more violent extremes of the

American and French Revolutions, but the desire for freedom and equality burned

just as heatedly in English breasts as it did in those of Americans and

Frenchmen. So it's not surprising that England produced six of its greatest

poets within a relatively short period of time: first Blake, then Wordsworth,

Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats. Each of the six seemed to coin a new, man-centric religion. Each of the six was

to some degree a heir of Blake's

reinterpreted Milton. Within a few years, other strikingly unique voices would

emerge, chief among them Walt Whitman, a romantic poet-prophet in the vein of

Blake. Like Blake, Whitman was a mystic, with a belief in the "oneness" and equality of

all life. Blake seems

to have made a definite impression on Whitman, as Whitman had his death-crypt

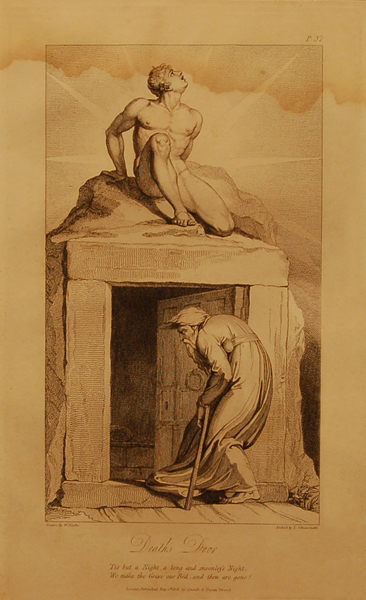

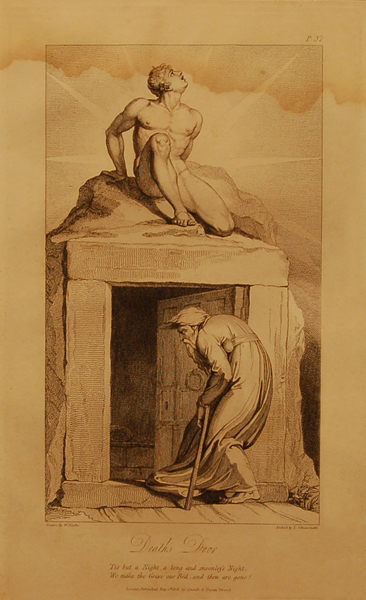

modeled after Blake's "Death's Door" ...

William Blake "Death's Door"

![[Blake Print - Songs of Innocence]](images/William%20Blake%20Songs%20of%20Innocence.jpg)

William Blake's "Songs of Innocence"

Songs of Innocence: The Chimney Sweeper

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! 'weep!

So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep.

There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head,

That curled like a lamb's back, was shaved: so I said,

"Hush, Tom! never mind it, for when your head's bare,

You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair."

And so he was quiet; and that very night,

As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight,―

That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack,

Were all of them locked up in coffins of black.

And by came an angel who had a bright key,

And he opened the coffins and set them all free;

Then down a green plain leaping, laughing, they run,

And wash in a river, and shine in the sun.

Then naked and white, all their bags left behind,

They rise upon clouds and sport in the wind;

And the angel told Tom, if he'd be a good boy,

He'd have God for his father, and never want joy.

And so Tom awoke; and we rose in the dark,

And got with our bags and our brushes to work.

Though the morning was cold, Tom was happy and warm;

So if all do their duty they need not fear harm.

Songs of Experience: The Chimney Sweeper

A little black thing in the snow,

Crying "'weep! 'weep!" in notes of woe!

"Where are thy father and mother? Say!"

"They are both gone up to the church to pray."

"Because I was happy upon the heath,

And smiled among the winter's snow,

They clothed me in the clothes of death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe."

"And because I am happy and dance and sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God and his priest and king,

Who make up a heaven of our misery."

Blake wrote one collection of poems called Songs of Innocence, and

another called Songs of Experience. The poems of the first collection

look at the world from the vantage of childish innocence, while the poems of the

second collection view the same world through the eyes of experience. In both

poems above we can feel Blake's tender empathy for suffering children.

In both poems the child chimneysweeps are so young they can't pronounce the "s"

in "sweep" and so mispronounce their job titles. If the first poem seems

hopeful, it may be simply because children are inclined to be hopeful, due to

their innocence. The second poem is much darker and we sense Blake's fury with

religious people who go to church and "pray" while innocent children suffer and

die. What would he make of Jews and Christian today, who go to churches and

synagogues, and endlessly read and study the Bible, but don't know better than to allow the children of Gaza to suffer and

die needlessly? I have no doubt that he would think as little of them as he did of the

slavemasters who used and abused children in the "jolly old England"

of his day.

Here are two more poems from the same collections:

Songs of Innocence: Holy Thursday

'Twas on a Holy Thursday, their innocent faces clean,

The children walking two & two, in red & blue & green,

Grey-headed beadles walk'd before, with wands as white as snow,

Till into the high dome of Paul's they like Thames' waters flow.

O what a multitude they seem'd, these flowers of London town!

Seated in companies they sit with radiance all their own.

The hum of multitudes was there, but multitudes of lambs,

Thousands of little boys & girls raising their innocent hands.

Now like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song,

Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of heaven among.

Beneath them sit the aged men, wise guardians of the poor;

Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.

Songs of Experience: Holy Thursday

Is this a holy thing to see,

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduced to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

Is that trembling cry a song!

Can it be a song of joy?

And so many children poor,

It is a land of poverty!

And their sun does never shine.

And their fields are bleak & bare.

And their ways are fill'd with thorns

It is eternal winter there.

For where-e'er the sun does shine,

And where-e'er the rain does fall:

Babe can never hunger there,

Nor poverty the mind appall.

The "Holy Thursday" of Songs of Innocence describes

the celebration of the ascension of Jesus. On this day, children from the charity schools of

London were marched to a service at St. Paul's Cathedral. The beadles were the

men in charge of keeping order. In the last

stanza of the poem, the children are singing in the balcony and the beadles

are seated below them. The final line is an allusion to Hebrews 13:2, "Be not

forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels

unawares."

The "Holy Thursday" from Songs of Experience describes the same ceremony.

When Blake says "It is eternal winter there," he seems to be saying that a

church that denies innocent children food

and a decent life is utterly lacking in light and warmth.

Here are two more poems from the same collections:

Songs of Innocence: The Lamb

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Gave thee life & bid thee feed,

By the stream & o'er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing, wooly, bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice?

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Little Lamb, I'll tell thee,

Little Lamb, I'll tell thee:

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb.

He is meek & he is mild;

He became a little child.

I a child & thou a lamb.

We are called by his name.

Little Lamb, God bless thee!

Little Lamb, God bless thee!

Songs of Experience: The Tyger

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes!

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire!

And what shoulder, & what art.

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand! & what dread feet!

What the hammer! what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain

What the anvil, what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spear

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see

Did he who made the Lamb make thee!

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry!

"The Lamb" from Songs of Innocence is highly symbolic. The lamb simultaneously symbolizes innocence, a human child, and Jesus.

"The Tyger" symbolizes experience, an adult and perhaps the Anti-Christ. A predator kills constantly. The poem asks the question: "Did he

who made the lamb make thee!" but with an exclamation mark rather than a question mark. Blake may be asking: are the men who inflict such suffering on

innocent children even human? He may have found it difficult to reconcile his humanity to the inhumanity of men capable of such brutality and

utter disregard for the suffering of innocents.

Here are two more poems from the same collections:

Songs of Innocence:

The Divine Image

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

All pray in their distress;

And to these virtues of delight

Return their thankfulness.

For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is God, our father dear,

And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love

Is Man, his child and care.

For Mercy has a human heart,

Pity a human face,

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

Then every man, of every dime

That prays in his distress,

Prays to the human form divine,

Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace.

And all must love the human form,

In heathen, turk, or jew;

Where Mercy, Love & Pity dwell

There God is dwelling too.

Songs of Experience: The Human Abstract

Pity would be no more,

If we did not make somebody Poor:

And Mercy no more could be,

If all were as happy as we;

And mutual fear brings peace;

Till the selfish loves increase.

Then Cruelty knits a snare,

And spreads his baits with care.

He sits down with holy fears,

And waters the ground with tears:

Then Humility takes its root

Underneath his foot.

Soon spreads the dismal shade

Of Mystery over his head;

And the Catterpiller and Fly,

Feed on the Mystery.

And it bears the fruit of Deceit,

Ruddy and sweet to eat;

And the Raven his nest has made

In its thickest shade.

The Gods of the earth and sea,

Sought thro' Nature to find this Tree

But their search was all in vain:

There grows one in the Human Brain

"The Divine Image" of Songs of Innocence attributes the virtues of

Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love to the human form and says that where these virtues

exist, "there God is dwelling too." Blake thus makes the point that if God dwells in every human being,

racism is nonsensical.

"The Divine Image" of Songs of

Experience appeared in only one copy of Songs of

Innocence and Experience. Many critics and scholars believe this is because Blake

considered the better companion poem for "The Divine Image" to be "The Human Abstract."

"The Human Abstract" also attributes Pity and Mercy to the human form, but

suggests that we feel pity and practice mercy only after we have caused other

people to suffer. Once again Blake seems to criticize religion, this time for

creating "holy fears" (perhaps the fear of hell) and false humility. The result

is darkness (perhaps superstition and false teachings) and deceit. The origin of

such things is not God or Nature, but the "Human Brain," which produces bad

theology and uncompassionate, unjust religions.

Blake was perhaps the most spiritual and mystical of English poets. He recorded having

visions of angels and said that he saw and conversed with the angel Gabriel, Mary, and various historical figures. At age four he had a vision of God

looking at him through a window. Around age nine he had a vision of "a tree

filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars." On

another occasion, Blake "watched haymakers at work and thought he saw angelic

figures walking among them." Blake also believed that he was personally

instructed and encouraged by Archangels.

In a letter to John Flaxman, dated 21 September 1800, Blake wrote: "[The town

of] Felpham is a sweet place for Study, because it is more spiritual than

London. Heaven opens here on all sides her golden Gates; her windows are not

obstructed by vapours; voices of Celestial inhabitants are more distinctly

heard, & their forms more distinctly seen; & my Cottage is also a Shadow of

their houses. My Wife & Sister are both well, courting Neptune for an embrace...

I am more famed in Heaven for my works than I could well conceive. In my Brain

are studies & Chambers filled with books & pictures of old, which I wrote &

painted in ages of Eternity before my mortal life; & those works are the delight

& Study of Archangels."

In a letter to Thomas Butts, dated 25 April 1803, Blake wrote: "Now I may say to

you, what perhaps I should not dare to say to anyone else: That I can alone

carry on my visionary studies in London unannoy'd, & that I may converse with my

friends in Eternity, See Visions, Dream Dreams & prophecy & speak Parables

unobserv'd & at liberty from the Doubts of other Mortals; perhaps Doubts

proceeding from Kindness, but Doubts are always pernicious, Especially when we

Doubt our Friends."

In one of his more mystical passages Blake wrote:

"To see a world in a grain of sand

And heaven in a wild flower

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour."

"If the doors of perception were cleansed

everything would appear to man as it is:

Infinite."

"He who binds to himself a joy,

Does the winged life destroy;

He who kisses the joy as it flies,

Lives in Eternity's sun rise."

William Blake's "The Parable of the Wise & Foolish Virgins"

According to Jonathan Jones, art critic for The Guardian, Blake is "far

and away the greatest [visual] artist Britain has ever produced." Blake has also

been included among the top forty artists of all time by G. Fernández and has

been called one of the greatest artists by John Ruskin, John Maynard, Henry

Fuseli, John Flaxman, Alexander Gilchrist and Ita Marguet, among others. Harold

Bloom, perhaps the best-known of modern literary critics, included Blake in his

list of the 100 greatest geniuses of all time, calling him a visionary akin to

Dante, Milton and Shelley. But perhaps the best measure of the genius of William

Blake is his influence on other poets and artists, including especially the

Romantics, and through them the Modernists and Post-Modernists. William

Wordsworth, the leading figure among the early Romantics, offered this verdict

after Blake's death: "There was no doubt that this poor man was mad, but there

is something in the madness of this man which interests me more than the sanity

of Lord Byron and Walter Scott."

Blake might be considered the first major Romantic poet, because he

combined imagination and individuality with contempt for mindless orthodoxy. He

was a modern Prometheus, shaking off the chains of orthodoxy and

authoritarianism, to seek the holy inner fire of passionate imagination.

Blake's "long, flowing lines and violent energy, combined with aphoristic

clarity and moments of lyric tenderness" heralded the free verse of poets like

Whitman. Where poets of the past had been poets of form and

precision, Blake was a poet of freer-flowing energy, passion and imagination. After Blake,

poets like Alexander Pope would often seem conventional and dull, for all their

talent, skill and dexterity. Blake raised the bar by caring deeply about his

subjects, and by requiring his readers to care and respond passionately in return.

Blake also influenced the pre-Raphaelites, Allen Ginsburg and the

Beat poets, the Underground Movement, the "counter culture," Percy Bysshe

Shelley, Algernon Charles Swinburne, James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, C.

S. Lewis, Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, U2, Salman Rushdie, Phillip Pullman ("His Dark

Materials"), Orson Scott Card, et al. The modern graphic novel can clearly trace its

roots to Blake's illuminated poems and prophetic books. And it seems likely that

every major anti-war and anti-orthodoxy figure since Blake has been influenced

to some degree by him.

Jim Morrison based the name of his rock group, the Doors,

on Blake's "doors of perception."

Bob Dylan collaborated with Allen Ginsberg to record two Blake songs. Ginsberg

even claimed that Blake's spirit had communicated musical settings of several Blake poems

to him. In 1948 he had an auditory hallucination of Blake reading his poems "Ah,

Sunflower," "The Sick Rose," and "Little Girl Lost" (later referred to as his

"Blake vision"). Patti Smith was heavily influenced by Blake, referring to him

in her song "My Blakean Year" and also reciting his poetry

before some of her songs.

William Rossetti called Blake a "glorious luminary," and described him as "a man

not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to

be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors."

In 1793's Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Blake "condemned the

cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the

right of women to complete self-fulfillment." He abhorred the black-robed

priests of organized religion who erected a "Thou shalt not" sign over his

garden of earthly love ...

The Garden Of Love

by William Blake

I laid me down upon a bank,

Where Love lay sleeping;

I heard among the rushes dank

Weeping, weeping.

Then I went to the heath and the wild,

To the thistles and thorns of the waste;

And they told me how they were beguiled,

Driven out, and compelled to the chaste.

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen;

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut

And "Thou shalt not," writ over the door;

So I turned to the Garden of Love

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tombstones where flowers should be;

And priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys and desires.

Blake was the inventor of relief etching, or illuminated printing, a method he

used to produce most of his books, paintings, pamphlets and poems. He also

employed intaglio engraving, most notably for the illustrations of the Book of

Job.

Blake's trouble with authority came to a head in August 1803, when he was

involved in a physical altercation with a soldier called John Schofield. Blake

was charged not only with assault, but also with uttering seditious and

treasonable expressions against the King. Schofield claimed that Blake had

exclaimed, "Damn the king. The soldiers are all slaves." Blake would be cleared

in the Chichester assizes of the charges. According to a report in the Sussex

county paper, "The invented character of [the evidence] was ... so obvious that

an acquittal resulted." Schofield was later depicted wearing "mind forged

manacles" in an illustration to Jerusalem.

Blake revolted against the established institutions of his time, saying:

"Prisons are built with stones of Law, brothels with bricks of Religion."

He sided with the rebellious fallen angels of Milton's "Paradise Lost" and

attacked conventional religious views, particularly those that called sex "evil"

and thus opposed human happiness. Some of Blake's contemporaries called

him a harmless lunatic, but by advocating free love and opposing misery-inducing

religious orthodoxy, he was simply light years ahead of his time. In Blake's

case it

seems madness really is "divinest sense."

One of Blake's lifelong concerns was to free the soul and its natural energies from

the hidebound "reason" of organized religion. He hated the grimy, sooty effects

of the Industrial Revolution in England and looked forward to the establishment

of a New Jerusalem "in England's green and pleasant land." His personal religion was

freedom, tolerance and the pursuit of happiness, without artificial limitations

and impediments. To him, religious orthodoxy was like a speed bump in the middle

of racetrack. He had a heart of all human suffering. But perhaps his greatest

enduring legacy is his tender empathy for

children, and his fierce, passionate defense of them.

William Blake's "Job"

The Heresies of William Blake

William Blake was a heretic who wrote:

The Vision of Christ that thou dost See

Is my Visions Greatest Enemy

…

Both read the Bible day & night

But thou readst black where I read White.

In the next poem Blake explicitly identified the Judaic/Christian creator-god with the Devil. Please keep in mind that Christians call Satan “the accuser of the brethren” and the “son

of the morning” …

To the Accuser Who Is the God of this World

Truly, my Satan, thou art but a Dunce,

And dost not know the Garment of the Man.

Every Harlot was a Virgin once,

Nor canst thou ever change Kate into Nan.

Tho’ thou art Worship’d by the Names Divine

Of Jesus and Jehovah, thou are still

The Son of Morn in weary Night’s decline,

The lost Traveller’s Dream under the Hill.

Blake saw Jesus as a good man and role model, not as a “savior,” and wrote in his criticism of Christian apologetics:

“all […] codes given under pretence of divine command were what Christ pronounced them, The Abomination that maketh desolate, i.e. State Religion” and later in the same text, “The

Beast & the Whore rule without control.”

I take the Beast to be the devilish biblical “god” and the Whore to be the church in the guise of a state religion (which now threatens American democracy).

Blake wrote companion poems “The Lamb” and “The Tyger” in which he condemned the Creator. In the first poem, misread if one reads it alone, he asked:

Little Lamb, who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

In “The Tyger” he disputed the Christian dogma of a benevolent Creator, asking the savage predator:

Did he who make the Lamb make thee?

Blake reversed the Bible’s ludicrous “original sin” episode and called the Christian church a “serpent temple” and its “god” a “tyrant crown’d”:

Then was the serpent temple form’d, image of infinite

Shut up in finite revolutions, and man became an Angel;

Heaven a mighty circle turning; God a tyrant crown’d.

Blake saw himself as a warrior engaged in a “mental fight” with the three-headed hydra of church, state and industry:

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Blake had a number of heretical opinions, among them that the Creator is the author of all evil; that Nature is not good but evil and humans and animals are its victims; that organized religion is Devil

worship; and that human beings must free themselves from the incorrect ideas of religion, which Blake called the “mind-forged manacles.”

Blake was also ahead of his time in advocating free love, tolerance for people of all races, the abolition of slavery, the abolition of child labor, etc.

One might call William Blake the "original flower child."

BLAKEAN POEMS

by Michael R. Burch

Ah! Sunflower

by Michael R. Burch

for and after William Blake

O little yellow flower

like a star ...

how beautiful,

how wonderful

we are!

The Difference

by Michael R. Burch

The chimneysweeps

will weep

for Blake,

who wrote his poems

for their dear sake.

The critics clap,

polite, for you.

Another poem

for poets,

Whooo!

Orpheus, or, William Blake's Whistle

by Michael R. Burch

for and after William Blake

I.

Many a sun

and many a moon

I walked the earth

and whistled a tune.

I did not whistle

as I worked:

the whistle was my work.

I shirked

nothing I saw

and made a rhyme

to children at play

and hard time.

II.

Among the prisoners

I saw

the leaden manacles

of Law,

the heavy ball and chain,

the quirt.

And yet I whistled

at my work.

III.

Among the children’s

daisy faces

and in the women’s

frowsy laces,

I saw redemption,

and I smiled.

Satanic millers,

unbeguiled,

were swayed by neither girl,

nor child,

nor any God of Love.

Yet mild

I whistled at my work,

and Song

broke out,

ere long.

A Passing Observation about Thinking Outside the Box

by Michael R. Burch

William Blake had no public, and yet he’s still read.

His critics are dead.

evol-u-shun

by michael r. burch

for and after william blake

does GOD adore the Tyger

while it’s ripping ur lamb apart?

does GOD applaud the Plague

while it’s eating u ŕ la carte?

does GOD admire ur brains

while ur claimng IT has a heart?

does GOD endorse the Bible

you blue-lighted at k-mart?

In the segmented title “evol” is “love” spelled backwards:

thus "love u shun." The title

questions whether you/we have been shunned by a "God of Love" and/or by

evolution. William Blake’s poem “The Tyger” questions the nature of

a Creator who brings innocent lambs and savage tigers into the same world.

the echoless green

by michael r. burch

for and after William Blake

at dawn, laughter rang

on the echoing green

as children at play

greeted the day.

by noon, smiles were seen

on the echoing green

as, children no more,

many fine oaths they swore.

come twilight, their cries

had subsided to sighs.

now Night reigns supreme

on the echoless green.

blake take

by michael r. burch

we became ashamed of our bodies;

we became ashamed of sweet sex;

we became ashamed of the LORD

for each terrible CURSE and HEX;

we became ashamed of the planet

(it’s such a slovenly hovel);

and we came to see, in the end,

that we really agreed with the devil.

dark matter(s)

by michael r. burch

for and after William Blake

the matter is dark, despairful, alarming:

ur Creator is hardly prince charming!

yes, ur “Great I Am”

created blake’s lamb

but He also created the tyger ...

and what about trump and rod steiger?

Rod Steiger is best known for his portrayals of weirdos, oddballs, mobsters,

bandits, serial killers, and fascists like Mussolini and Napoleon.

tyger, lamb, free love, etc.

by michael r. burch

for and after william blake

the tiger’s a ferocious slayer.

he has no say in it.

hence, ur Creator’s a shit.

the lamb led to the slaughter

extends her neck to the block and bit.

she has no say in it.

so don’t be a nitwit:

drink, carouse and revel!

why obey the Devil?

beMused

by Michael R. Burch

Perhaps at three

you'll come to tea,

to have a cuppa here?

You'll just stop in

to sip dry gin?

I only have a beer.

To name the “greats”:

Pope, Dryden, mates?

The whole world knows their names.

Discuss the “songs”

of Emerson?

But these are children's games.

Give me rhythms

wild as Dylan’s!

Give me Bobbie Burns!

Give me Psalms,

or Hopkins’ poems,

Hart Crane’s, if he returns!

Or Langston railing!

Blake assailing!

Few others I desire.

Or go away,

yes, leave today:

your tepid poets tire.

I Learned Too Late

by Michael R. Burch

“Show, don’t tell!”

I learned too late that poetry has rules,

although they may be rules for greater fools.

In any case, by dodging rules and schools,

I avoided useless duels.

I learned too late that sentiment is bad—

that Blake and Keats and Plath had all been had.

In any case, by following my heart,

I learned to walk apart.

I learned too late that “telling” is a crime.

Did Shakespeare know? Is Milton doing time?

In any case, by telling, I admit:

I think such rules are shit.

Mongrel Dreams (II)

by Michael R. Burch

for Thomas Rain Crowe

I squat in my Cherokee lodge, this crude wooden hutch of dry branches and

leaf-thatch

as the embers smolder and burn,

hearing always the distant tom-toms of your rain dance.

I relax in my rustic shack on the heroned shores of Gwynedd,

slandering the English in the amulet gleam of the North Atlantic,

hearing your troubadour’s songs, remembering Dylan.

I stand in my rough woolen kilt in the tall highland heather

feeling the freezing winds through the trees leaning sideways,

hearing your bagpipes’ lament, dreaming of Burns.

I slave in my drab English hovel, tabulating rents

while dreaming of Blake and burning your poems like incense.

I abide in my pale mongrel flesh, writing in Nashville

as the thunderbolts flash and the spring rains spill,

till the quill gently bleeds and the white page fills,

dreaming of Whitman, calling you brother.

Related pages: The Best Poems and Art of William Blake,

William Blake Famous Poems,

William Blake's Influence,

William Blake's Angels,

William Blake: Heretic,

William Blake's Jesus Christ,

William Blake's God

The HyperTexts

![[Blake Print - Angels Hovering Over the Body of Jesus in the Sepulchre]](images/William%20Blake%20Angels%20Hovering%20Over%20the%20Body%20of%20Jesus%20Christ.jpg)

![[Blake Print - Jacob's Ladder]](images/William%20Blake%20Jacobs%20Ladder.jpg)

![[Blake Print - Angels Hovering Over the Body of Jesus in the Sepulchre]](images/William%20Blake%20Angels%20Hovering%20Over%20the%20Body%20of%20Jesus%20Christ.jpg)

![[Blake Print - Jacob's Ladder]](images/William%20Blake%20Jacobs%20Ladder.jpg)

![[Blake Print - Hecate]](images/William%20Blake%20Hecate.jpg)

![[Blake Print - Songs of Innocence]](images/William%20Blake%20Songs%20of%20Innocence.jpg)