The HyperTexts

American Sapphos

Who are the American Sapphos?

The American heirs of Sappho include Anne Reeve Aldrich, Louise Bogan,

Emily Dickinson, Adah Isaacs Menken, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sarah Teasdale, Dorothy Parker, Sylvia Plath and Anne

Sexton. When I first conceived of this page, I had three female poets in mind:

Sappho, Aldrich and Dickinson. Later, I discovered a fourth American Sappho, Adah

Isaacs Menken. As if to confirm that I was on the right path,

during my research the Universe (or at least the Internet, care of

Google) provided the following images ...

Artistic rendering of Sappho by William Adolphe Bouguereau

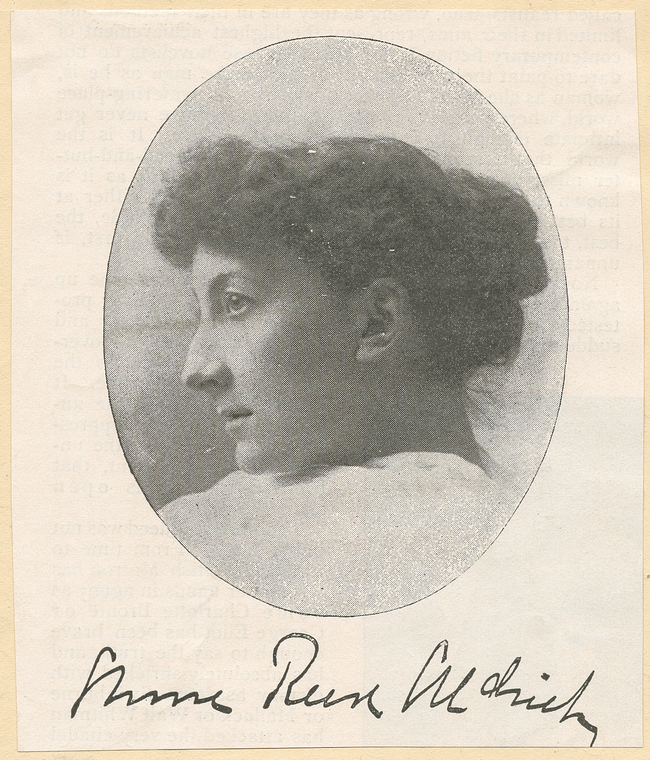

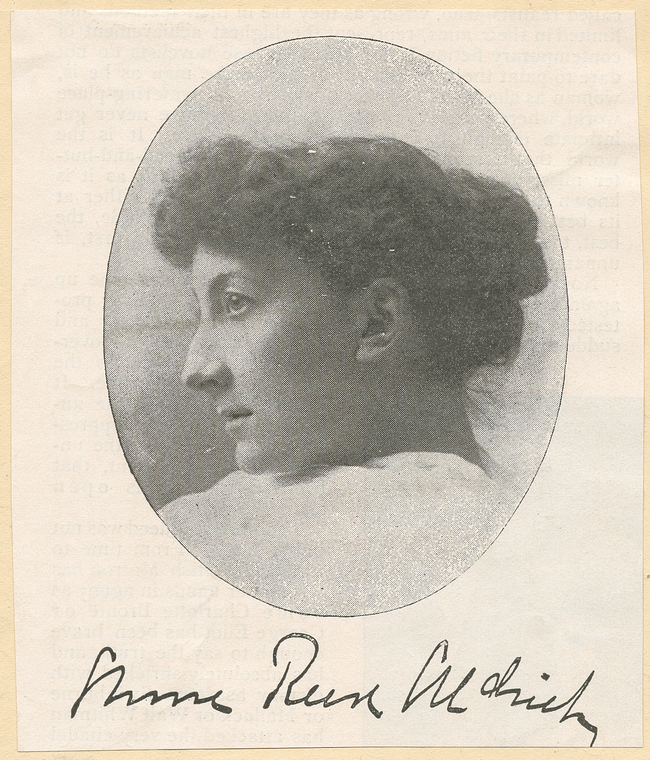

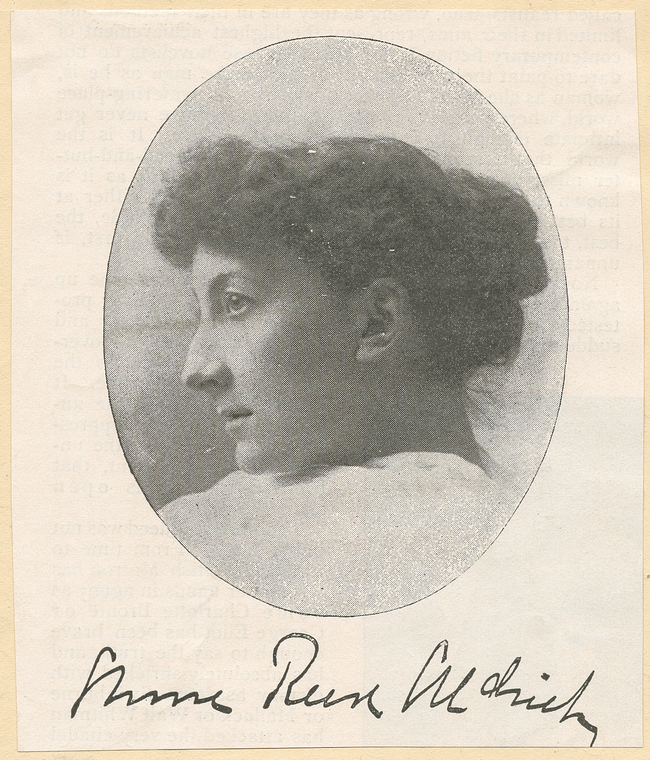

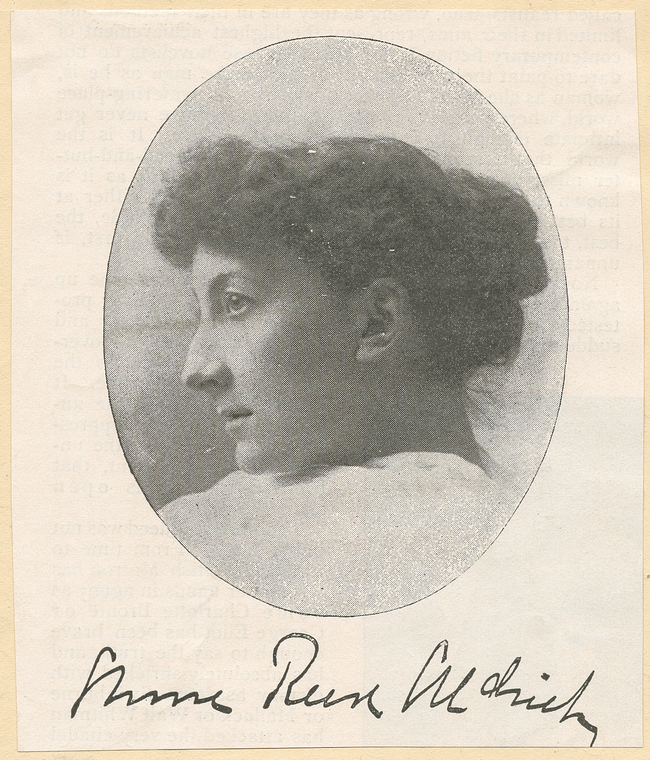

Anne Reeve Aldrich

Emily Dickinson

Adah Isaacs Menken

There does seem to be a striking family resemblance. But what I'm most interested in is the

Sapphic poetry, by which I do not mean homoerotic or erotic poetry, per se, but

poetry that is deeply felt and passionately and honestly expressed ...

Artistic rendering of Sappho by William Adolphe Bouguereau

Sappho of Lesbos is the first great female poet still known to us by name today,

and she remains one of the very best poets of all time, regardless of gender.

She is so associated with erotic love poetry that we get our terms "sapphic" and "lesbian" from her name

and island of residence. As you can see from the stellar epigrams

below, she remains a timeless treasure:

Sappho, fragment 42

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

Eros harrows my heart:

wild winds whipping desolate mountains,

uprooting oaks.

Sappho, fragment 155

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

A short transparent frock?

It's just my luck

your lips were made to mock!

Sappho, fragment 156

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

She keeps her scents

in a dressing-case.

And her sense?

In some undiscoverable place.

Anne Reeve Aldrich [1866-1892] was an

American poet and novelist. She wrote a number

of poems in which she seemed to prophesy an early death, then indeed died young at the tender

age of 26. According to the preface of Songs about Life, Love, and Death, which was published posthumously, at

the time of her death she was so weak that she couldn’t lift her pen, and thus

had to dictate her last poem, “Death at Daybreak.” Aldrich published her first volume of poetry, The Rose

of Flame in 1889; it was not well received; critics cited its "unrestrained

expression." She was also accused of having written “erotic” poems. But she

persevered, publishing a novel, The Feet of Love, in 1890, and it seems

she was working on her final volume of poems even on her deathbed.

Servitude

The church was dim at vespers.

My eyes were on the Rood.

But yet I felt thee near me,

In every drop of blood.

In helpless, trembling bondage

My soul's weight lies on thee,

O call me not at dead of night,

Lest I should come to thee!

Aldrich was an heir of Sappho particularly in her worship of earthly love. A

number of times in her poems Aldrich explicitly either rejected orthodox

Christianity, or put it aside, in order to pursue romantic love with no mention

of matrimony. Also, in the poem below Aldrich, like Sappho, attributes her

talent for singing to a heart wounded by love (the rose-thorns):

A Song About Singing

O nightingale, the poet's bird,

A kinsman dear thou art,

Who never sings so well as when

The rose-thorns bruise his heart.

But since thy agony can make

A listening world so blest,

Be sure it cares but little for

Thy wounded, bleeding breast!

Here, Aldrich seems to pray to Love as Sappho once prayed to Aphrodite, the

Goddess of Love:

In Conclusion

O Love, take these my songs, made for thy joy,

And speak one tender word of them to me.

And other praise or blame that word will drown

As voice of brook is drowned by sounding sea.

Like all my joys and woes, my garnered verse

To lay at thy dear feet I haste to bring.

Be gracious. Love, remembering that the mouth

Touched by thine own, could scarcely fail to sing!

The poem of Aldrich's below reminds me not only of Sappho, but also of Christina

Rossetti, one of the very best English female poets. Aldrich sounds most like

Sappho when she says, "Think how my eyes grew brighter at thy coming, / Think of

those fervid noontides in the South." This is, in my opinion, a magnificent

poem, but even more importantly, a very moving poem:

When I Was Thine

"Ricordati da me quand 'ero teco." Tuscan Rispetto.

THE sullen rain breaks on the convent window,

The distant chanting dies upon mine ears.

—Soon comes the morn for which my soul hath languished,

For which my soul hath yearned these many years;

Forget of me this life which I resign,

Think of me in the days when I was thine.

Forget the paths my weary feet have travelled,

The thorns and stones that pierced them as I went;

These later days of prayer and scourge and penance,

These hours of anguish now so nearly spent.

Forget I left thy life for life divine,

Think of me in the days when I was thine.

Forget the rigid brow as thou wilt see it,

The folded eyelids, and the quiet mouth.

Think how my eyes grew brighter at thy coming,

Think of those fervid noontides in the South.

Think when my kisses made life half divine,

Think of me in the days when I was thine.

Forget this nearer past, I do adjure thee,

Remember only what was long ago.

Think when our love was fire unquenched by ashes,

Think of our Spring, and not this Winter's snow.

Forget me as I lie, past speech or sign.

Think of me in the days when I was thine.

In the poem below, it may be that Aldrich, who to my knowledge never married,

"repented" of not having "gone all the way" (the "one sweet sin"?). But by

embracing her desire to have committed adultery, she would have been

"unrepentant" in the eyes of orthodox Christianity, so her soul might be

considered to be "lost." I think Aldrich is saying that she considers her soul

to be lost because she cannot honestly "repent" of her desire to commit "that

one sweet sin," even on her deathbed.

Outer Darkness

Where shall I look for help? Our gracious God

Pities all those who weep for sin ingrain,

And potent is the Kingly Victim's blood

To wash repented guilt, and leave no stain.

But ah, what hope for me in Heaven above,

What consolation left beneath the sun,

In those black hours when my lost soul laments

Because it left that one sweet sin undone?

It seems Aldrich's lover rejected her. One possibility is that he was devoutly

religious, perhaps even a priest. If so, the "bitter cup" below might be a

communion cup, containing sacramental wine. Did her lover loathe Aldrich because

of her strong sexual desires? Of course this is speculation on my part, but

perhaps the "pleasure" the cup held was the comfort of Christianity, and the

scorn Aldrich endured was the scorn of Christianity for female sexuality outside

marriage.

A Draught

A bitter cup you offer me,

Though roses hide its brim with red.

Yet since your strong hand proffers it,

I shall not spurn, but drink instead.

And when the draught has done its work.

And I lie low, who now stand high.

You, who encompassed this, will pass

With loathing and averted eye.

Yet none the less I humbly bow.

And drain the cup on bended knee.

That holds within its hollow gold

Your pleasure, and your scorn of me.

Aldrich lived in a very different and difficult world for young women who prized

romantic, sexual love above religion. As with Sappho, her poems ring with the

truth that romantic love is holy.

There are hints in the poems of Emily Dickinson that she may have had an affair,

or near affair, with a man of the cloth or a devout Christian. For instance in

the lines below she sounds quite a bit like Anne Reeve Aldrich (in content,

although not in style):

They’d judge us—how?

For you served Heaven, you know,

Or sought to;

I could not,Because you saturated sight,

And I had no more eyes

For sordid excellence

As Paradise.

And were you lost, I would be,

Though my name

Rang loudest

On the heavenly fame.

And were you saved,

And I condemned to be

Where you were not,

That self were hell to me.

In this poem Dickinson speaks eloquently of the power of love, a transforming

power:

He touched me, so I live to know

That such a day, permitted so,

I groped upon his breast.

It was a boundless place to me,

And silenced, as the awful sea

Puts minor streams to rest.

And now, I’m different from before,

As if I breathed superior air,

Or brushed a royal gown;

My feet, too, that had wandered so,

My gypsy face transfigured now

To tenderer renown.

The poem below is certainly more passionate than demure. But was Emily Dickinson

writing to a man, a woman, more than one person, or just imaginatively?

Wild nights! Wild nights!

Were I with thee,

Wild nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile the winds

To a heart in port,—

Done with the compass,

Done with the chart.

Rowing in Eden!

Ah! the sea!

Might I but moor

To-night in thee!

Here, when Dickinson speaks of the "imperial heart" she sounds like Sappho and

Aldrich:

Father, I bring thee not myself,—

That were the little load;

I bring thee the imperial heart

I had not strength to hold.

The heart I cherished in my own

Till mine too heavy grew,

Yet strangest, heavier since it went,

Is it too large for you?

When we think of Emily Dickinson, it is all too easy to think of her as a

sexless recluse, but that may not be the case.

The following are excerpts from the letters of Emily Dickinson to her

brother's family, edited by Martha Dickinson Bianchi, who was Emily Dickinson's

niece. The Susan addressed so tenderly is Susan Gilbert Dickinson, the wife of Emily Dickinson's

brother. As I read these

letters for the first time, I felt that I had misapprehended Emily

Dickinson. It seems apparent

from her letters that she had a soul mate in Susan Dickinson. I was very touched reading

her letters, and I feel that I know and understand her a

little better for having read them. She certainly seems to have been a disciple

of Love, like Sappho.—MRB

Unable are the dead to die

For love is immortality,

Nay it is Deity.

*

Sometimes with the heart,

Seldom with the soul,

Scarcely once with the night—

Few love at all.

*

Of so divine a loss

We enter but the gain,

Indemnity for loneliness

That such a bliss has been.

*Susan—I dreamed

of you, last

night, and send

a Carnation to

indorse it—

Sister of Ophir —

Ah Peru —

Subtle the Sum

That purchase

you —

*

Susan knows she is a Siren and at a word from her Emily would forfeit

righteousness—

Your little mental gallantries are sweet as chivalry,—which is to me a

shining word though I don't know what it means.

It would be good to see the grass and hear the wind blow that wide way through

the orchard. Are the apples ripe? Have the wild geese crossed? And did you save

the seed of the pond-lily? Do not cease, dear. Should I turn in my long night I

should murmur "Sue" . . .

To take you away leaves but a lower world, your firmamental quality our more

familiar sky.

How tenderly I thank you, Sue, for every solace! . . . Beneath the Alps the Danube runs.

Now, farewell, Susie, and Vinnie sends her love, and mother hers, and I add a

kiss, shyly, lest there is somebody there! Don't let them see, will you Susie?

It's a sorrowful morning Susie—the wind blows and it rains; "into each life some

rain must fall," and I hardly know which falls fastest, the rain without, or

within—Oh Susie, I would nestle close to your warm heart, and never hear the

wind blow, or the storm beat, again. Is there any room there for me, darling,

and will you "love me more if ever you come home"?—it is enough, dear Susie, I

know I shall be satisfied. But what can I do towards you?—dearer you cannot be,

for I love you so already, that it almost breaks my heart—perhaps I can love you

anew, every day of my life, every morning and evening—Oh if you will let me, how

happy I shall be!

Susie, forgive me Darling, for every word I say — my heart is full of you, none

other than you is in my thoughts, yet when I seek to say to you something not

for the world, words fail me. If you were here — and Oh that you were, my Susie,

we need not talk at all, our eyes would whisper for us, and your hand fast in

mine, we would not ask for language — I try to bring you nearer, I chase the

weeks away till they are quite departed, and fancy you have come, and I am on my

way through the green lane to meet you, and my heart goes scampering so, that I

have much ado to bring it back again, and learn it to be patient, till that dear

Susie comes.

The last line Emily Dickinson sent, not long before her death, "in

response to an entreaty for an assurance of her certainty of our love and

continuance of her own" was: "Remember, dear, that an unmitigated Yes is my only reply to your

utmost question."

Adah Isaacs Menken (1835-1868) was an American ballet dancer, tightrope

walker, vaudevillian,

painter and poet, and the highest-earning actress of her day.

The details of Menken's origins, including her maiden name, place of birth, ancestry,

and religion remain murky, because she gave different accounts at different times

in her life. She has been called the first Jewish-American superstar, but

may

have been a Louisiana Creole of mixed race, fathered by a free negro, at a time

when it was considered scandalous to have black blood. In any case, as a child going by "Ada Theodore," she performed as a ballet

dancer at the French Opera House in New Orleans and in Havana, where she was crowned "Queen of the Plaza."

She then turned to the stage and became a touring actress.

But the young Ada wanted to be known as a writer. Her early work was devoted to

family; after her marriage at age 21 to a Jewish musician, Alexander Isaac

Menken, her poetry and essays featured Jewish themes. But then he left her,

according to Samuel Dickinson, for smoking cigarettes in public!

She added an "h" to her first name and an "s" to her middle name, but eventually

became so famous that she was known simply as "the Menken." In 1859

she

appeared in the Broadway play The French Spy. Her work was

not highly regarded by critics. The New York Times described her as "the

worst actress on Broadway." According to the Observer she was "delightfully

unhampered by the shackles of talent." However, she continued to perform small

parts, to read Shakespeare and to give lectures. Menken became an

"early master of self-promotion" by having photographs of her striking face appear in shop windows wherever

she performed.

Around this time she remarried. Her second husband, John Carmel Heenan, was a

popular bare knuckle boxer. While he was in London for an 1860 match

that has been called the first boxing world championship, Menken billed herself as

Mrs. John Heenan for a successful one-night run at the Old Bowery Theatre. She

made similar bookings in Boston, Providence, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, using

his name even after their divorce.

While in New York, Menken met Walt Whitman, the poet who originated American

free verse. In 1860 Menken wrote a

review entitled "Swimming Against the Current" in which she praised Whitman's

Leaves of Grass, calling him "centuries ahead of his

contemporaries." Such a comment could have seemed scandalous in polite

quarters, as Whitman had been accused of "obscenity" for writing frankly about the human body,

sex and homosexuality. Menken updated her own style and became the "first poet and the only woman poet

before the twentieth century" to follow Whitman's free verse lead. Menken was

also an early advocate of women's rights, including the

right not to marry. At this time, Menken wore her wavy hair cropped short and

cultivated a bohemian, androgynous appearance. She was, in a word, notorious. In

1860-61, she published 25 poems in the Sunday Mercury, an entertainment

newspaper. By publishing in a newspaper rather than

women's magazines she was able to reach a larger audience, including male readers who might pay to see her act.

Menken did a vaudeville tour with Charles Blondin, the famous tightrope walker. After the tour ended, she asked her manager Jimmie

Murdock to help her become recognized as a great actress. Murdock countered

with the "breeches role" of a noble Tartar in the melodrama Mazeppa,

which was

based on a poem by Lord Byron. At the climax of the play, the Tartar was

stripped of his clothing, tied to his horse, and sent off to his death. Audiences were thrilled with the scene, although the production used a dummy

strapped to a horse, which was led away by a handler with sugar cubes. Menken

performed the stunt herself. Dressed in nude-colored stockings and

riding a horse on stage, she appeared to be naked and caused a sensation. She

was also toying with the conventions of gender, a century before Boy George and Lady Gaga. New York audiences were shocked but attended

in large enough numbers to make the play popular. Menken then took Mazeppa to San Francisco,

where

audiences less concerned about convention made it a smash hit. According to Dickinson she was very

popular with the "gay blades" and the two topics on everyone's minds were the

progress of the Civil War and whatever Menken was up to. She was wooed by Bret

Harte and other eligible men, but chose a young American

humorist, Robert Henry Newell, for her third husband. The marriage to Newell

lasted two years, after which she married a James Paul Barkley, about whom

little is known except that he may have been a gambler. That marriage is

reported to have lasted a Kardashian-like three days. Menken was

ahead of her time in a number of ways!

Menken then took Mazeppa abroad and quickly conquered London and Paris.

The sensational aspects of the production attracted attention before the show

opened

at the Astley Theatre to "overflowing houses."

This period established her fame and notoriety. She

attracted male admirers such as Charles Dickens, Tom Hood, Dante Gabriel

Rossetti, and Charles Reade. She allegedly had

affairs with Alexandre Dumas père, who was more than twice her

age, and Algernon Charles Swinburne. Unfortunately,

Menken fell ill in London and was forced to stop performing. Her fame and

fortune dissipated quickly, and due to her excessive generosity she soon struggled with poverty. She died

in Paris in 1868 and was buried in the Jewish section of

Montparnasse Cemetery, where the inscription on her tomb reads "Thou knowest."

Her only book Infelicia, a collection of 31 poems, was published just days

after her death. The book went through several editions and remained in print

until 1902.

Dying

I

Leave me; oh! leave me,

Lest I find this low earth sweeter than the skies.

Leave me lest I deem Faith's white bosom bared to the betraying arms of Death.

Hush your fond voice, lest it shut out the angel trumpet-call!

See my o'erwearied feet bleed for rest.

Loose the clinging and the clasping of my clammy fingers.

Your soft hand of Love may press back the dark, awful shadows of Death, but the

soul faints in the strife and struggles of nights that have no days.

I am so weary with this climbing up the smooth steep sides of the grave wall.

My dimmed eyes can no longer strain up through the darkness to the temples and

palaces that you have built for me upon Life's summit.

God is folding up the white tent of my youth.

My name is enrolled for the pallid army of the dead.

Aspiration

Poor, impious Soul! that fixes its high hopes

In the dim distance, on a throne of clouds,

And from the morning's mist would make the ropes

To draw it up amid acclaim of crowds―

Beware! That soaring path is lined with shrouds;

And he who braves it, though of sturdy breath,

May meet, half way, the avalanche and death!

O poor young Soul!―whose year-devouring glance

Fixes in ecstasy upon a star,

Whose feverish brilliance looks a part of earth,

Yet quivers where the feet of angels are,

And seems the future crown in realms afar―

Beware! A spark thou art, and dost but see

Thine own reflection in Eternity!

Answer Me

I

In from the night.

The storm is lifting his black arms up to the sky.

Friend of my heart, who so gently marks out the lifetrack for me, draw near

to-night;

Forget the wailing of the low-voiced wind:

Shut out the moanings of the freezing, and the starving, and the dying, and bend

your head low to me:

Clasp my cold, cold hands in yours;

Think of me tenderly and lovingly:

Look down into my eyes the while I question you, and if you love me, answer me—

Oh, answer me!

II

Is there not a gleam of Peace on all this tiresome earth?

Does not one oasis cheer all this desert-world?

When will all this toil and pain bring me the blessing?

Must I ever plead for help to do the work before me set?

Must I ever stumble and faint by the dark wayside?

Oh the dark, lonely wayside, with its dim-sheeted ghosts peering up through

their shallow graves!

Must I ever tremble and pale at the great Beyond?

Must I find Rest only in your bosom, as now I do?

Answer me—

Oh, answer me!

III

Speak to me tenderly.

Think of me lovingly.

Let your soft hands smooth back my hair.

Take my cold, tear-stained face up to yours.

Let my lonely life creep into your warm bosom, knowing no other rest but this.

Let me question you, while sweet Faith and Trust are folding their white robes

around me.

Thus am I purified, even to your love, that came like John the Baptist in the

Wilderness of Sin.

You read the starry heavens, and lead me forth.

But tell me if, in this world's Judea, there comes never quiet when once the

heart awakes?

Why must it ever hush Love back?

Must it only labor, strive, and ache?

Has it no reward but this?

Has it no inheritance but to bear—and break?

Answer me—

Oh, answer me!

IV

The Storm struggles with the Darkness.

Folded away in your arms, how little do I heed their battle!

The trees clash in vain their naked swords against the door.

I go not forth while the low murmur of your voice is drifting all else back to

silence.

The darkness presses his black forehead close to the window pane, and beckons me

without.

Love holds a lamp in this little room that hath power to blot back Fear.

But will the lamp ever starve for oil?

Will its blood-red flame ever grow faint and blue?

Will it uprear itself to a slender line of light?

Will it grow pallid and motionless?

Will it sink rayless to everlasting death?

Answer me—

Oh, answer me!

V

Look at these tear-drops.

See how they quiver and die on your open hands.

Fold these white garments close to my breast, while I question you.

Would you have me think that from the warm shelter of your heart I must go to

the grave?

And when I am lying in my silent shroud, will you love me?

When I am buried down in the cold, wet earth, will you grieve that you did not

save me?

Will your tears reach my pale face through all the withered leaves that will

heap themselves upon my grave?

Will you repent that you loosened your arms to let me fall so deep, and so far

out of sight?

Will you come and tell me so, when the coffin has shut out the storm?

Answer me—

Oh, answer me!

One Year Ago

In feeling I was but a child,

When first we met―one year ago,

As free and guileless as the bird,

That roams the dreary woodland through.

My heart was all a pleasant world

Of sunbeams dewed with April tears:

Life's brightest page was turned to me,

And naught I read of doubts or fears.

We met―we loved―one year ago,

Beneath the stars of summer skies;

Alas! I knew not then, as now,

The darkness of life's mysteries.

You took my hand―one year ago,

Beneath the azure dome above,

And gazing on the stars you told

The trembling story of your love.

I gave to you―one year ago,

The only jewel that was mine;

My heart took off her lonely crown,

And all her riches gave to thine.

You loved me, too, when first we met,

Your tender kisses told me so.

How changed you are from what you were

In life and love―one year ago.

With mocking words and cold neglect,

My truth and passion are repaid,

And of a soul, once fresh with love,

A dreary desert you have made.

Why did you fill my youthful life

With such wild dreams of hope and bliss?

Why did you say you loved me then,

If it were all to end in this?

You robbed me of my faith and trust

In all Life's beauty―Love and Truth,

You left me nothing―nothing save

A hopeless, blighted, dreamless youth.

Strike if you will, and let the stroke

Be heavy as my weight of woe;

I shall not shrink, my heart is cold,

'Tis broken since one year ago.

A Memory

I see her yet, that dark-eyed one,

Whose bounding heart God folded up

In His, as shuts when day is done,

Upon the elf the blossom's cup.

On many an hour like this we met,

And as my lips did fondly greet her,

I blessed her as love's amulet:

Earth hath no treasure, dearer, sweeter.

The stars that look upon the hill,

And beckon from their homes at night,

Are soft and beautiful, yet still

Not equal to her eyes of light.

They have the liquid glow of earth,

The sweetness of a summer even,

As if some Angel at their birth

Had dipped them in the hues of Heaven.

They may not seem to others sweet,

Nor radiant with the beams above,

When first their soft, sad glances meet

The eyes of those not born for love;

Yet when on me their tender beams

Are turned, beneath love's wide control,

Each soft, sad orb of beauty seems

To look through mine into my soul.

I see her now that dark-eyed one,

Whose bounding heart God folded up

In His, as shuts when day is done,

Upon the elf the blossom's cup.

Too late we met, the burning brain,

The aching heart alone can tell,

How filled our souls of death and pain

When came the last, sad word, Farewell!

Infelix

Where is the promise of my years;

Once written on my brow?

Ere errors, agonies and fears

Brought with them all that speaks in tears,

Ere I had sunk beneath my peers;

Where sleeps that promise now?

Naught lingers to redeem those hours,

Still, still to memory sweet!

The flowers that bloomed in sunny bowers

Are withered all; and Evil towers

Supreme above her sister powers

Of Sorrow and Deceit.

I look along the columned years,

And see Life’s riven fane,

Just where it fell, amid the jeers

Of scornful lips, whose mocking sneers,

For ever hiss within mine ears

To break the sleep of pain.

I can but own my life is vain

A desert void of peace;

I missed the goal I sought to gain,

I missed the measure of the strain

That lulls Fame’s fever in the brain,

And bids Earth’s tumult cease.

Myself! alas for theme so poor

A theme but rich in Fear;

I stand a wreck on Error’s shore,

A spectre not within the door,

A houseless shadow evermore,

An exile lingering here.

Working And Waiting

Suggested by Carl Müller's Cast of the Seamstress, at the Dusseldorf Gallery.

I

Look on that form, once fit for the sculptor!

Look on that cheek, where the roses have died!

Working and waiting have robbed from the artist

All that his marble could show for its pride.

Statue-like sitting

Alone, in the flitting

And wind-haunted shadows that people her hearth.

God protect all of us—

God shelter all of us

From the reproach of such scenes upon earth!

Judith

'Repent, or I will come unto thee quickly, and will fight thee with the sword of

my mouth.'

―Revelation ii. 16.

I

Ashkelon is not cut off with the remnant of a valley.

Baldness dwells not upon Gaza.

The field of the valley is mine, and it is clothed in verdure.

The steepness of Baal-perazim is mine;

And the Philistines spread themselves in the valley of Rephaim.

They shall yet be delivered into my hands.

For the God of Battles has gone before me!

The sword of the mouth shall smite them to dust.

I have slept in the darkness-

But the seventh angel woke me, and giving me a sword of flame, points to the

blood-ribbed cloud, that lifts his reeking head above the mountain.

Thus am I the prophet.

I see the dawn that heralds to my waiting soul the advent of power.

Power that will unseal the thunders!

Power that will give voice to graves!

Graves of the living;

Graves of the dying;

Graves of the sinning;

Graves of the loving;

Graves of the despairing;

And oh! graves of the deserted!

These shall speak, each as their voices shall be loosed.

And the day is dawning.

II

Stand back, ye Philistines!

Practice what ye preach to me;

I heed ye not, for I know ye all.

Ye are living burning lies, and profanation to the garments which with stately

steps ye sweep your marble palaces.

Ye places of Sin, around which the damning evidence of guilt hangs like a

reeking vapor.

Stand back!

I would pass up the golden road of the world.

A place in the ranks awaits me.

I know that ye are hedged on the borders of my path.

Lie and tremble, for ye well know that I hold with iron grasp the battle axe.

Creep back to your dark tents in the valley.

Slouch back to your haunts of crime.

Ye do not know me, neither do ye see me.

But the sword of the mouth is unsealed, and ye coil yourselves in slime and

bitterness at my feet.

I mix your jeweled heads, and your gleaming eyes, and your hissing tongues with

the dust.

My garments shall bear no mark of ye.

When I shall return this sword to the angel, your foul blood will not stain its

edge.

It will glimmer with the light of truth, and the strong arm shall rest.

III

Stand back!

I am no Magdalene waiting to kiss the hem of your garment.

It is mid-day.

See ye not what is written on my forehead?

I am Judith!

I wait for the head of my Holofernes!

Ere the last tremble of the conscious death-agony shall have shuddered, I will

show it to ye with the long black hair clinging to the glazed eyes, and the

great mouth opened in search of voice, and the strong throat all hot and reeking

with blood, that will thrill me with wild unspeakable joy as it courses down my

bare body and dabbles my cold feet!

My sensuous soul will quake with the burden of so much bliss.

Oh, what wild passionate kisses will I draw up from that bleeding mouth!

I will strangle this pallid throat of mine on the sweet blood!

I will revel in my passion.

At midnight I will feast on it in the darkness.

For it was that which thrilled its crimson tides of reckless passion through the

blue veins of my life, and made them leap up in the wild sweetness of Love and

agony of Revenge!

I am starving for this feast.

Oh forget not that I am Judith!

And I know where sleeps Holofernes.

Related pages:

Romanticism Then and Now,

Romanticism Defined, The Best

Romantic Poetry, The Best Romantic

Poets, American Sapphos

The HyperTexts