The HyperTexts

The Best Romantic Poetry, or, "Who put the 'ah!' in 'stars'?"

The following are, in my opinion, among the very best Romantic poems of all time,

by the very best Romantic poets. On

this page I will attempt to trace the brilliant-but-elusive thread of

Romanticism from the mists of Greek and Anglo-Saxon antiquity, through precursors of

English Romanticism like Edmund Spenser, Thomas Wyatt, John Donne and John

Milton, on to the "big six" of William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, John Keats

and

Percy Bysshe Shelley. I will also include early American Romantics like Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Alan Poe, along with Ireland's Tom Moore,

Scotland's Robert Burns and France's Charles Baudelaire

and Victor Hugo. Modern Romantics include Conrad Aiken,

Louise Bogan, Hart

Crane, e. e. cummings, T. S. Eliot, Ernest Dowson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Wilfred Owen,

Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Dylan

Thomas, William Butler Yeats and Oscar Wilde. Unknown or "under-known" poets who

merit consideration include two exceptional poets who died in their teens:

Thomas Chatterton and Digby Mackworth Dolben. I will also include contemporary

Romantics like

Kevin N. Roberts and

Mary Rae.

compiled by Michael R. Burch

The first great lyric

poet of antiquity, and perhaps the first Romantic poet we know by name today, was

Sappho of Lesbos ...

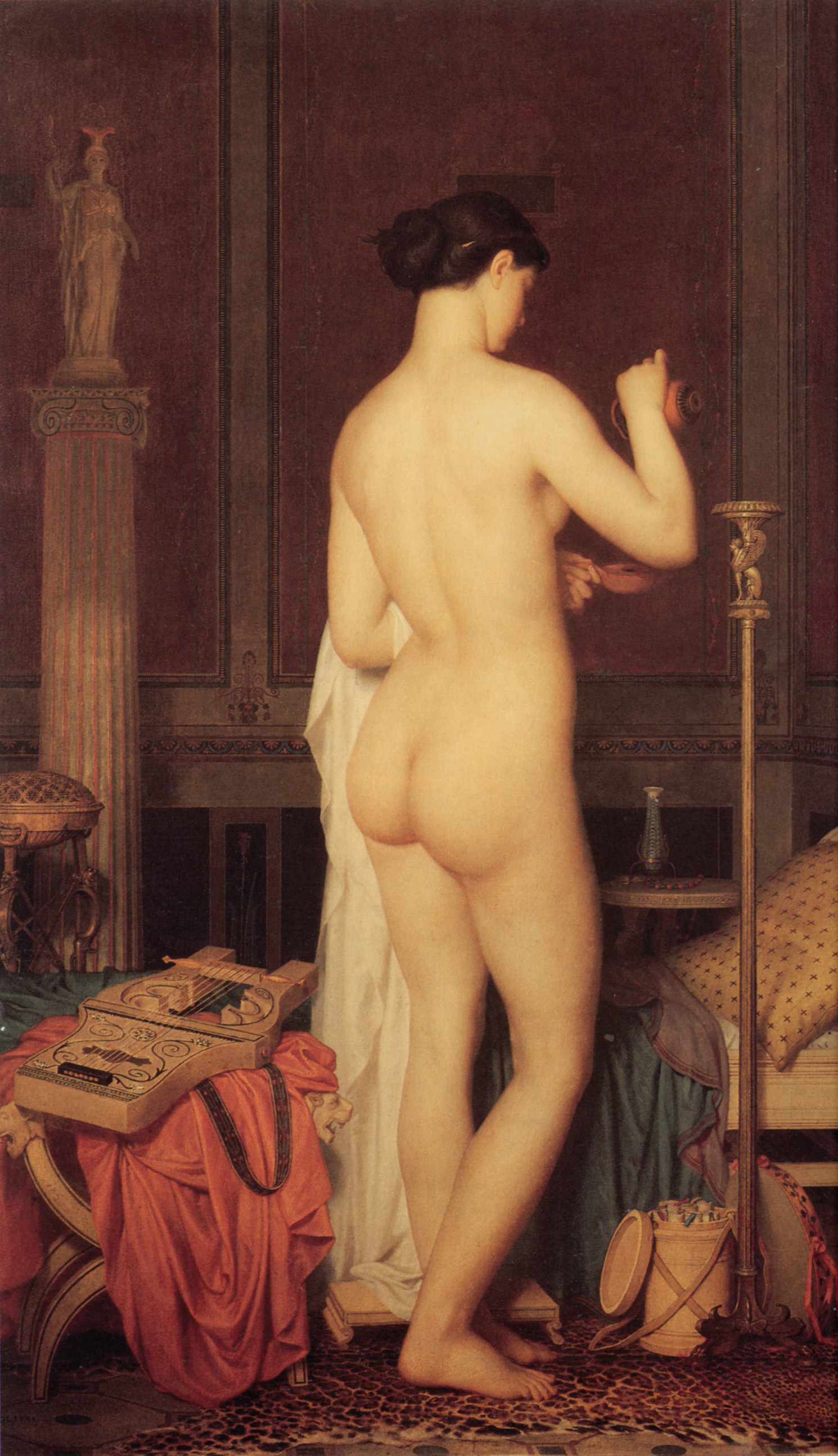

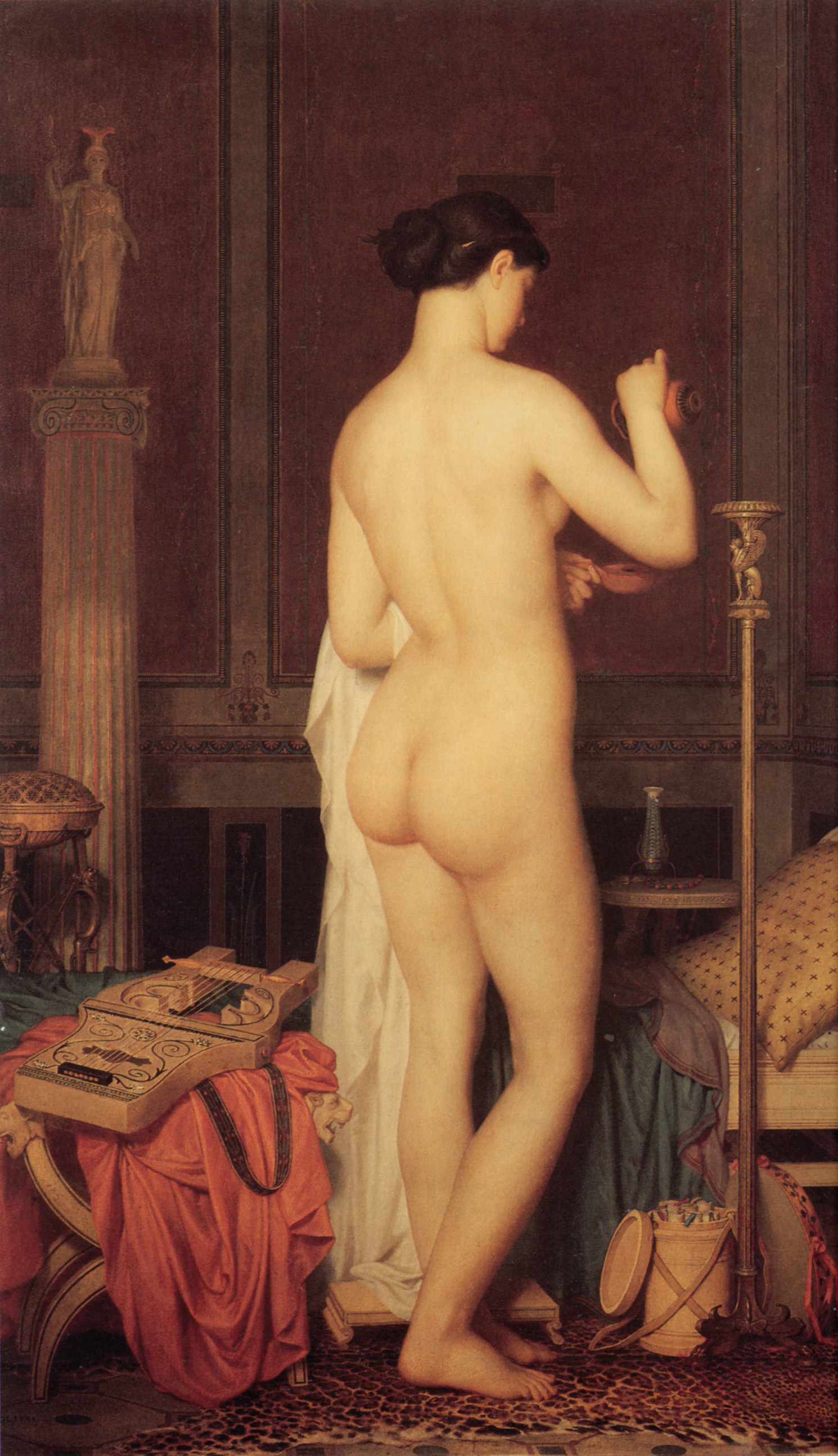

Gleyre Le Coucher de Sappho

by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre

Sappho of Lesbos (c. 630 BC-570 BC) is perhaps the first great female poet still known to us

by name today,

and she remains one of the very best poets of all time, regardless of gender.

She is so revered for her erotic love poetry that we get our terms "sapphic" and "lesbian" from her name

and island of residence. And as you can see from the two stellar epigrams

below, she remains a timeless treasure:

Sappho, fragment 42

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

Eros harrows my heart:

wild winds whipping desolate mountains,

uprooting oaks.

Sappho, fragment 155

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

A short transparent frock?

It's just my luck

your lips were made to mock!

A Brief History of English Romantic Poetry, compiled by Michael R. Burch (some dates

are approximations):

5600 BC — Rising seas separate England from the European

mainland; one consequence is that the natives' language begins to evolve

separately from its continental peers ...

1268 BC — This is Robert Graves' date for the

Song of Amergin, but dating such orally-transmitted works of the

Prehistoric Period is a highly speculative

endeavor!

55 BC — Julius Caesar invades England beginning the

Anglo-Roman Period

(55 BC-410 AD). Latin is the language of rulers, clergy and scholars. Native poetry

is oral.

410 AD — Rome is sacked; the Roman legions no longer

defend England and Germanic tribes invade, beginning the

Anglo-Saxon or

Old English Period (410-1066).

658 —

Caedmon's Hymn, the

oldest authenticated English poem, marks the

beginning of English poetry (although it was

Anglo-Saxon and thus still heavily Germanic).

950 — The Exeter Book contains the first

English poems likely written by women,

Wulf and Eadwacer

and

The Wife's Lament, and the first English rhyming poem.

1066 — William the Conqueror wins at Hastings; this Norman Conquest

begins the Anglo-Norman or Middle English Period

(1066-1340). French and Latin rule.

1000 —

Now skruketh rose and lylie flour is one of the earliest and best

English love poems. English has gone underground but still survives.

1200 —

How Long the Night

("Myrie it is while sumer

ylast") is one of the best Middle English

rhyming poems.

1260 —

Rhyme rules with

Sumer is icumen in,

Fowles in the Frith,

Ich

am of Irlaunde ("I am of Ireland"),

Now Goeth Sun Under Wood,

Pity Mary.

1340 — Geoffrey Chaucer is the first major poet to write

in English, beginning the Late Middle

English Period (1340-1503).

1430 — A "haunting riddle-chant" from this era is

I Have a Yong Suster.

1485 — The Tudor Period (1457-1603) ends the Middle Ages. English rules over French, finally! William Dunbar's

"Sweet Rose of Virtue."

1500 ― The great early English ballads such as "Sir

Patrick Spens," "Edward," "The Unquiet Grave" and "Lord Randal."

1503 —

Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard introduce

the sonnet, iambic pentameter and blank verse, beginning the

English Renaissance or Early Modern English Period

(1503-1558).

1558 — The Elizabethan Period (1558-1603)

features major

works by Edmund Spenser, Walter Ralegh, Philip Sidney, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare.

1603 — The

Jacobean/Caroline/Interregnum/Restoration Period (1603-1690)

features the King James Bible, Ben Jonson, John Donne, John Milton, Robert

Herrick.

1690 — The Augustan Period (1690-1756)

features sophisticated work by Alexander Pope, John Dryden, Samuel Johnson, et

al. (But it seems like a dry spell today.)

1752 —

Thomas Chatterton

was called the "marvellous boy"

by William Wordsworth. Although he died at age seventeen, Chatterton has been called the first

modern Romantic poet.

1757 — The

English Romantic Period (1757-1837) stars William Blake, William Wordsworth,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, Robert

Burns.

1800 — American Romantics include Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Alan Poe, Herman Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson,

Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson.

1837 — The Victorian Period (1837-1900) stars

Alfred Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, Gerard Manley Hopkins,

John Clare, Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

1848 — The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1848-1882) was founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti; aligned poets

were

Christina Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne.

1900 — Leading voices of Modernism and

Postmodernism (1901-Present) include Ernest Dowson, William Butler Yeats,

Thomas Hardy, A. E. Housman, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens,

D. H.

Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, Conrad Aiken,

Wilfred Owen, e. e. cummings, Louise Bogan, Hart Crane,

Langston Hughes, W. H. Auden, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell,

Dylan Thomas, Sylvia Plath, Adele, Leonard Cohen, Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, Eminem,

Woody Guthrie, Michael Jackson, Carole King, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Willie

Nelson, Prince, Smokey Robinson, Pete Seeger, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and

Hank Williams Sr.

1969 ― Kevin N. Roberts, the founder and first editor of

Romantics Quarterly, claimed to be the

reincarnation of Swinburne and some of his fans believed he wrote that well ...

"Rondel" by

Kevin N. Roberts

Our time has passed on swift and careless feet,

With sighs and smiles and songs both sad and sweet.

Our perfect hours have grown and gone so fast,

And these are things we never can repeat.

Though we might plead and pray that it would last,

Our time has passed.

Like shreds of mist entangled in a tree,

Like surf and sea foam on a foaming sea,

Like all good things we know can never last,

Too soon we'll see the end of you and me.

Despite the days and realms that we amassed,

Our time has passed.

"Safe Harbor" by

Michael R. Burch

for Kevin N. Roberts

The sea at night seems

an alembic of dreams—

the moans of the gulls,

the foghorns’ bawlings.

A century late

to be melancholy,

I watch the last shrimp boat as it steams

to safe harbor again.

In the twilight she gleams

with a festive light,

done with her trawlings,

ready to sleep . . .

Deep, deep, in delight

glide the creatures of night,

elusive and bright

as the poet’s dreams.

The poem above was written in 2001 after a discussion

about Romanticism in the late 20th century. Mary Rae was the second editor of

Romantics Quarterly and also provided

the exquisitely lovely covers of the issues she edited.

"Season" by

Mary Rae

I

Youth and love unite beneath the power

of velvet skin and dark, half-sleeping eyes.

Spring seems to last forever to the flower

that feels the rush of chlorophyll's green rise.

Time is not—cannot be of the essence

when second hands are slow, standing still,

while all around the sun is streaming gold.

The thought of end, of beauty's obsolescence,

seems unreasonable and cannot hold

as long as love is dressed in daffodil.

II

Youth never sees itself or has a reason

to know that it has no infinity.

It turns, like spring, a sweet, unknowing season,

never doubting its divinity.

But as in fall trees look down on their leaves

that once had been too much a part to see,

powerless to reconstitute the whole;

so age sees fallen beauties and it grieves

the unclothing of the lonely soul

that, now in rags, goes begging tree to tree.

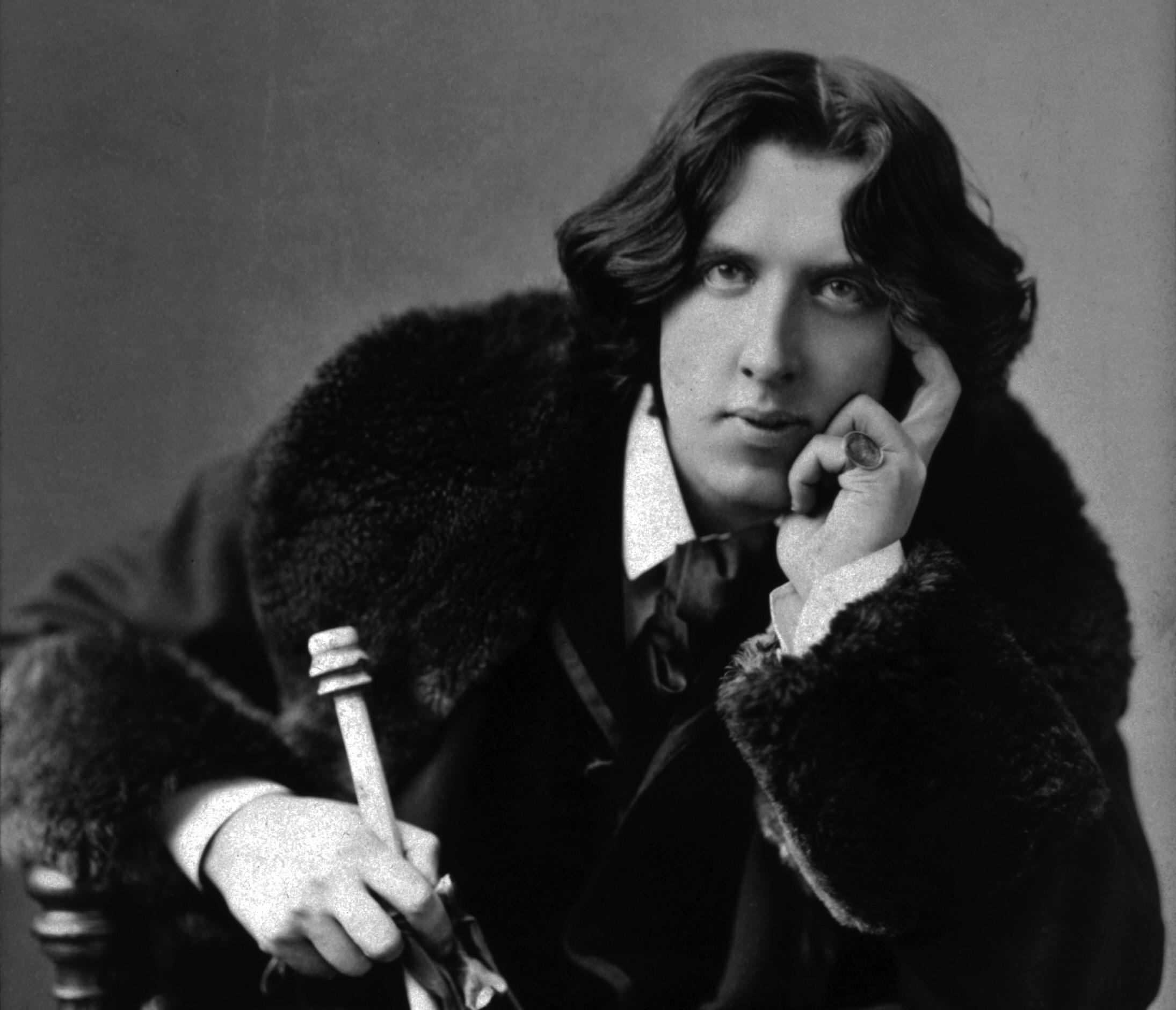

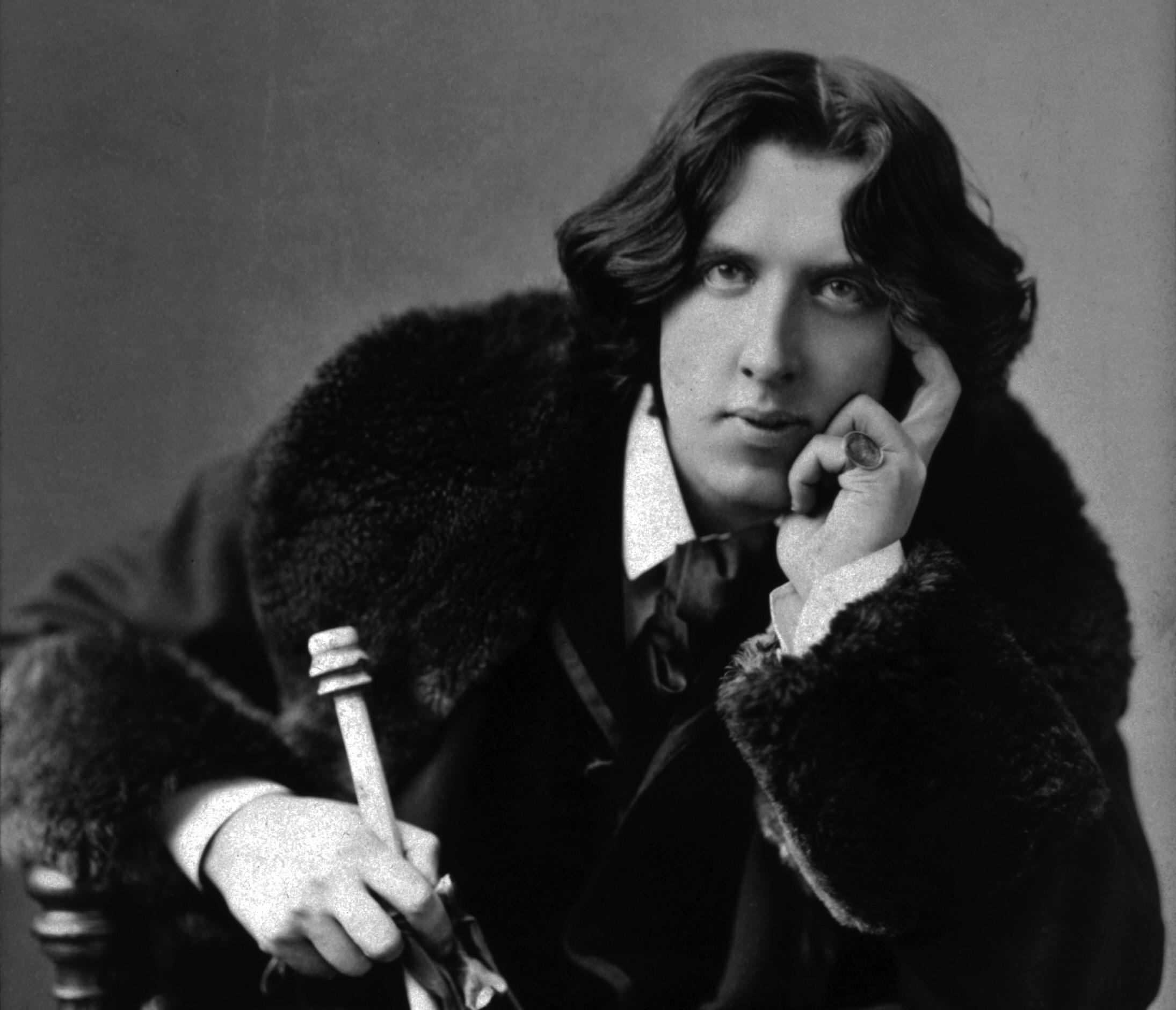

Oscar Wilde may be the most notorious "bad boy" in the annals of poetry and

literature. He was flamboyantly gay at a time when polite society was prim,

proper and violently homophobic. As a result, he was sentenced to hard labor at

Reading Gaol and died soon after his release. Wilde is justly famous today for

his disdain for "respectability" and dull and dulling conformity, as his witty

epigrams prove. But the lovely, wonderfully moving poem below proves that he was

also a great Romantic poet.

"Requiescat"

by Oscar Wilde

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

All her bright golden hair

Tarnished with rust,

She that was young and fair

Fallen to dust.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

Coffin-board, heavy stone,

Lie on her breast,

I vex my heart alone,

She is at rest.

Peace, Peace, she cannot hear

Lyre or sonnet,

All my life's buried here,

Heap earth upon it.

"Bread and Music" by Conrad Aiken

Music I heard with you was more than music,

And bread I broke with you was more than bread;

Now that I am without you, all is desolate;

All that was once so beautiful is dead.

Your hands once touched this table and this silver,

And I have seen your fingers hold this glass.

These things do not remember you, belovèd,

And yet your touch upon them will not pass.

For it was in my heart you moved among them,

And blessed them with your hands and with your eyes;

And in my heart they will remember always,—

They knew you once, O beautiful and wise.

"Music When Soft Voices Die (To —)" by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory—

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.

Rose leaves, when the rose is dead,

Are heaped for the belovèd's bed;

And so thy thoughts, when thou art gone,

Love itself shall slumber on.

William Butler Yeats was the most famous Irish poet of all time, and his

unrequited love for the beautiful and dangerous revolutionary Maud Gonne helped

make her almost as famous as he was in Ireland. The moving poem below is Yeats'

loose translation of a Ronsard poem, in which Yeats imagines the love of his

life in her later years tending a fire. The second poem below, "The Wild Swans

at Coole" is surely one of the most beautiful poems ever written, in any

language.

When You Are Old

by William Butler Yeats

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

The Wild Swans at Coole

by William Butler Yeats

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

Upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine and fifty swans.

The nineteenth Autumn has come upon me

Since I first made my count;

I saw, before I had well finished,

All suddenly mount

And scatter wheeling in great broken rings

Upon their clamorous wings.

I have looked upon those brilliant creatures,

And now my heart is sore.

All’s changed since I, hearing at twilight,

The first time on this shore,

The bell-beat of their wings above my head,

Trod with a lighter tread.

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold,

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

But now they drift on the still water

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake’s edge or pool

Delight men’s eyes, when I awake some day

To find they have flown away?

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was an early advocate of women's rights, and a

staunch opponent of slavery. When she married Robert Browning, theirs became the

most famous coupling in the annals of English poetry.

How Do I Love Thee?

by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love with a passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood's faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints,—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Dylan Thomas's elegy to his dying father is the best villanelle in the English

language, in my opinion, and one of the most powerful and haunting poems ever

written in any language.

Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Song for the Last Act

by Louise Bogan

Now that I have your face by heart, I look

Less at its features than its darkening frame

Where quince and melon, yellow as young flame,

Lie with quilled dahlias and the shepherd's crook.

Beyond, a garden. There, in insolent ease

The lead and marble figures watch the show

Of yet another summer loath to go

Although the scythes hang in the apple trees.

Now that I have your face by heart, I look.

Now that I have your voice by heart, I read

In the black chords upon a dulling page

Music that is not meant for music's cage,

Whose emblems mix with words that shake and bleed.

The staves are shuttled over with a stark

Unprinted silence. In a double dream

I must spell out the storm, the running stream.

The beat's too swift. The notes shift in the dark.

Now that I have your voice by heart, I read.

Now that I have your heart by heart, I see

The wharves with their great ships and architraves;

The rigging and the cargo and the slaves

On a strange beach under a broken sky.

O not departure, but a voyage done!

The bales stand on the stone; the anchor weeps

Its red rust downward, and the long vine creeps

Beside the salt herb, in the lengthening sun.

Now that I have your heart by heart, I see.

Epitaph for a Romantic Woman

by Louise Bogan

She has attained the permanence

She dreamed of, where old stones lie sunning.

Untended stalks blow over her

Even and swift, like young men running.

Always in the heart she loved

Others had lived,—she heard their laughter.

She lies where none has lain before,

Where certainly none will follow after.

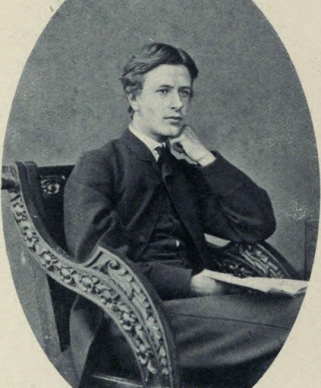

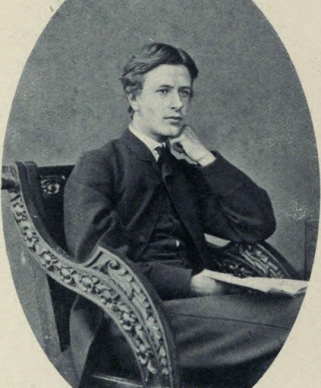

On a warm summer afternoon in 1867, Digby Mackworth Dolben drowned at

age nineteen. The poems he left behind were said by future English poet laureate Robert Bridges to

equal "anything that was ever written by any English poet at his age."

According to Simon Edge, author of The Hopkins Conundrum, Gerard Manley Hopkins was "so captivated by a brief meeting [with Dolben] that he spent the rest of his

life mourning him." In a letter to Bridges after

Dolben’s death, Hopkins said "there can very seldom have happened the loss of so

much beauty (in body and mind and life) and of the promise of still more as

there has been in his case." Hopkins also asked Bridges whether Dolben's family

had considered publishing his poems. Fortunately, the independently wealthy

Bridges later published books of poems by both Dolben and Hopkins, or their

poetry might have been lost to the world forever.

Is Dolben merely a literary curiosity today because he attracted the attention

of two famous poets―with possible homoerotic

undertones on Hopkins' part―then died so young

and so tragically? Or does he merit consideration as a poet in his own right?

After his discovery of the prodigy's work thanks to Simon's novel, THT advisory

editor Tom Merrill emailed Simon that "Dolben's precocity surprised me―how

beyond his years he was. I hope people know about him. He was a deeply sensitive

person, maybe comparable to Shelley." Another poet to whom Dolben may be

compared is Thomas Chatterton, the "marvellous boy" who died at age seventeen

and yet was so highly esteemed by Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats and Shelley.

A Song

by Digby Dolben, age 16-19

The world is young today:

Forget the gods are old,

Forget the years of gold

When all the months were May.

A little flower of Love

Is ours, without a root,

Without the end of fruit,

Yet ― take the scent thereof.

There may be hope above,

There may be rest beneath;

We see them not, but Death

Is palpable ― and Love.

Was Thomas Chatterton the greatest child prodigy in the history of poetry, or

was he a forger and fraud? That Chatterton was among the most remarkable of

child prodigies is hard to dispute, because at age ten he was writing

poems that were published, and by his early teens he had taught himself medieval

English and was producing poems by a fictitious poet, Thomas Rowley, in the language and style of Chaucer

and his contemporaries. The young Chatterton taught

himself to write in the "ye olde Englische" style, and to use ocher

and other chemicals to age the

"discovered" manuscripts to make them look medieval. While his compositions were

far from perfect, in terms of complying with all the complicated rules of that

long-ago day, and were eventually exposed as modern work, some of the poems were

so good they enchanted the great Romantic poets who saw Chatterton as one of

them. Was the child an evil genius, or were there, perhaps, perfectly good and

understandable reasons for his deceptions?

Before we proceed, please allow me to make the point that if Chatterton's poems

have artistic merit, there really isn't a case to be made against him. If he

told the truth and really did find the poems, then he was an honest boy who was

very unfairly criminalized. On the other hand, if he wrote the poems himself, he

was not a "forger," but an unusually original and gifted artist at a

very young age. In either case, where is the case against him? I don't think

there is one. But a valid question remains: how good were the poems he wrote,

since it seems rather obvious that he did write the poems? Great poets like

William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, Percy

Bysshe Shelley and John Keats praised the lad and claimed he was one of them.

Presumably, great poets should know great poetry when they read it. So let's

take a look at a poem that I believe rivals Shakespeare's best songs in his

plays ...

Song from Ælla: Under the Willow Tree, or, Minstrel's Roundelay

by Thomas Chatterton, age 17

O SING unto my roundelay,

O drop the briny tear with me;

Dance no more at holy-day,

Like a running river be:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Black his cryne as the winter night, cryne = crown, hair;

"Black his crown/hair/locks/etc."

White his rode as the summer snow, rode = complexion;

"White his skin/flesh/etc."

Red his face as the morning light,

Cold he lies in the grave below:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Sweet his tongue as the throstle's note,

Quick in dance as thought can be,

Deft his tabor, cudgel stout;

O he lies by the willow-tree!

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Hark! the raven flaps his wing

In the briar'd dell below;

Hark! the death-owl loud doth sing

To the nightmares, as they go:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

See! the white moon shines on high;

Whiter is my true-love's shroud:

Whiter than the morning sky,

Whiter than the evening cloud:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Here upon my true-love's grave

Shall the barren flowers be laid;

Not one holy saint to save

All the coldness of a maid:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

With my hands I'll dent the briars dent = fasten,

gird, frame; "With my hands I'll frame the briars"

Round his holy corse to gre:

corse = corpse (?); gre = grow; "Round his

holy corpse to grow"

Ouph and fairy, light your fires, ouph = elf;

"Elf and Fairy"

Here my body still shall be:

Here my body still shall go"

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Come, with acorn-cup and thorn,

Drain my heartès blood away;

Life and all its good I scorn,

Dance by night, or feast by day:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

The following is a poem from the mists of time and the dawn of the English

language ...

Wulf and Eadwacer (anonymous Anglo-Saxon poem, circa 990 AD)

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

My clan's curs pursue him like crippled game.

They'll rip him apart if he approaches their pack.

We are so different.

Wulf's on one island; I'm on another.

His island's a fortress, fastened by fens.

Here bloodthirsty men howl for sacrifice.

They'll rip apart if he approaches their pack.

We are so different.

My thoughts pursued Wulf like panting hounds.

Whenever it rained and I wept, disconsolate,

big, battle-strong arms grabbed and embraced me.

Good feelings for him, but for me loathsome!

Wulf, oh, my Wulf! My desire for you

has made me sick; your seldom-comings

have left me famished, deprived of real meat.

Do you hear, Heaven-Watcher? A wolf has borne

our wretched whelp to the woods.

One can easily sever what never was one:

our song together.

Translator's Notes: This may be the first extant poem authored by a woman in the

then-fledgling English language. "Wulf and Eadwacer" might also be called the

first English feminist text, as the speaker seems to be challenging and mocking

the man who has been raping and impregnating her. The poem's closing metaphor of

a loveless relationship being like a song in which two voices never harmonized

remains one of the strongest in the English language, or any language.

I will now continue on to the present day. There are over one billion speakers of English

in the modern world and most, if not all, seem to be poets. So I've had to narrow my scope to the very best

poems by the very best poets. For instance, take this darkly romantic poem by an American master:

"Acquainted With The Night" by Robert Frost

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain—and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain.

I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet

When far away an interrupted cry

Came over houses from another street,

But not to call me back or say good-by;

And further still at an unearthly height,

One luminary clock against the sky

Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

Mary Elizabeth Frye is, perhaps, the most mysterious poet who appears on this

page, and perhaps in the annals of poetry. Rather than spoiling the mystery, I

will present her poem first, then provide the details ...

Do not stand at my grave and weep

by Mary Elizabeth Frye

Do not stand at my grave and weep:

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

I am the soft starshine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry:

I am not there; I did not die.

This consoling elegy had a

very mysterious genesis, as it was written by Mary Elizabeth Frye, a

Baltimore housewife who lacked a formal education, having been orphaned at age

three. She had never written poetry before. Frye wrote the poem on a ripped-off piece of a brown grocery bag,

in a burst of compassion for a Jewish girl who had fled the Holocaust

only to receive news that her mother had died in Germany. The girl was

weeping inconsolably because she couldn't visit her mother's grave to share her

tears of love and bereavement. When the poem was named Britain's

most popular poem in a 1996 Bookworm poll, with more than 30,000

call-in votes despite not having been one of the critics'

nominations, an unlettered orphan girl had seemingly surpassed all England's

many cultured and degreed ivory towerists in the public's estimation. Although the poem's

origin was disputed for some time (it had been attributed to Native American and other sources),

Frye's authorship was confirmed in 1998 after investigative research by Abigail

Van Buren, the newspaper columnist better known as "Dear Abby." The poem has

also been called "I Am" due to its rather biblical repetitions of the phrase.

Frye never formally published or copyrighted the poem, so we believe it is in

the public domain and can be shared, although we recommend that it not be used

for commercial purposes, since Frye never tried to profit from it herself.

While you may quibble with my definition of "Romantic," I don't think you'll quibble with the

poems themselves. If you don't care for essays, please proceed directly to the poems. If you're interested in hearing a brief,

somewhat tongue-in-cheek history of

Romanticism first, here goes . . .

Romanticism Then and Now

"Define your terms!"

So Sophocles, the wisest man in ancient Greece, persistently insisted,

and so I immediately find myself at a sticky point in this essay, because

"Romanticism" and "Romantic" are among the most nebulous of terms. Rather than using

various excellent (but

not necessarily helpful) definitions, I will instead warp back in time to the very

first poet and tap into that first

bright vein of Romanticism which soon became the motherlode of all poetry . . .

We find our first cave-poet in a pickle of a predicament, because he's a pounded-upon,

beaten-down, intensely hairy, foul-smelling troglodyte almost totally

bereft of language. What's worse, he's trying to attract a mate, and all

the other male troglodytes are far hairier and fouler-smelling than he!

They have every alpha-male advantage! What is our despised, wordless, nameless poet to do? The object of his affection,

known to him longingly as Grunt, studiously ignores him because her other suitors supply her with

great hunks of raw mastodon haunch, while he has only a few albino

termites to proffer. His cause seems hopeless . . .

Until, one night, staring up miserably at the stars that seem to wink knowingly

overhead, mocking his plight, he has a sudden revelation. The stars glitter like crystals he has

seen littering certain tracts of stony ground nearby. Risking life and stubby

limb, he dashes past a few catnapping sabertooths to scoop up as much of the

glittery quartz as he can manage to carry and not be eaten alive. Hands full of

iridescent symbols of his adoring longing, he rushes back to the communal cave,

finds Grunt, and proceeds to dump out his treasure at her fulsomely hairy feet.

Tentatively, she picks up a crystal and licks it. Nope, it's not salt,

although if it had been salt it would have been an impressive gift. She

grunts, fidgets, frowns, quickly loses interest, then starts looking for something

more edible,

settling on a juicy anteater carcass recently brought to her by a suitor she thinks

of admiringly as Belch.

Our ignominious poet, so nondescript Grunt hasn't even bothered to assign him

a sound-name, is now totally despondent. If he can't communicate

his idea to her, his cause is lost. There'll be no tiny male troglodyte to

replicate his genes (which means no poetry for us, today). Forlornly, he

moons up at the stars, then, overtaken by wonder and awe, begins suddenly to

mouth new, strange, never-before-heard sounds: ah, ah!, stars! Excitedly, he points

up at the night's brilliant panorama of stars, then to the crystals shining at Grunt's

beaver-pelt-feet. Stars! Stars!

She looks blankly at him for a moment, then suddenly she gets it. Shrimp

bring Grunt stars? In humankind's first moment of tenderness not

attributable to the procurement of foodstuffs, she has bequeathed upon him her

sound-name for the most scrumptious of all the delicacies she knows.

More importantly, Shrimp and Grunt have made the great simultaneous leap to

sounds, words, metaphor, artistic imagination, and the communication and transference of

emotion. This delightful mélange, I call Romanticism, especially when the emotion conveyed is

somehow exaggerated in the process. Romanticism is, by my definition,

primarily amplification of emotion. Now that statement will probably make many

intellectuals wince. Aren't we talking about, shudder, overstatement? Yes,

we are. As we proceed, I will illustrate that the best poets do indeed engage in extravagance,

in hyperbole, in overstatement.

It is my contention

that the best poets do pretty much what Shrimp did so many millennia ago:

they impress the people they want to impress—then potential mates, now

primarily readers—by amplifying emotion. We moderns have become so

accustomed to words that we sometimes

forget the "ah!" in "stars," the tinkle in

"laughter," the hiss of danger in "sinister." But the best poets don't forget these things, nor do they take them for

granted. Instead, the best poets use every weapon in the poetic arsenal of

incendiary devices to conjure emotion. Poems are crafted of words just as buildings are

crafted of stone. It is a Romantic impulse that causes a Christopher Wren to imagine

St. Paul's Cathedral rather than a stone hovel; it is a similar Romantic impulse

that causes our friend Shrimp to imagine he can give Grunt the "ah!" in "stars."

But now let me move beyond my clumsy attempts to apply a stethoscope to the

Romantic (im)pulse, and get on to the really good (nay, the wondrous) stuff, the

poems . . .

"The Snow Man" by Wallace Stevens

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the

snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

"Piano" by D. H. Lawrence

Softly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;

Taking me back down the vista of years, till I see

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom of the tingling strings

And pressing the small, poised feet of a mother who smiles as she sings. In

spite of myself, the insidious mastery of song

Betrays me back, till the heart of me weeps to belong

To the old Sunday evenings at home, with winter outside

And hymns in the cozy parlor, the tinkling piano our guide. So now it is vain

for the singer to burst into clamor

With the great black piano appassionato. The glamour

Of childish days is upon me, my manhood is cast

Down in the flood of remembrance, I weep like a child for the past.

"The Garden" by Ezra Pound

Like a skein of loose silk blown against a wall

She walks by the railing of a path in Kensington Gardens,

And she is dying piece-meal

of

a sort of emotional anemia.

And round about there is a rabble

Of the filthy, sturdy, unkillable infants of the very poor.

They shall inherit the earth. In her is the end of breeding.

Her boredom is exquisite and excessive.

She would like some one to speak to her,

And is almost afraid that I

will commit that indiscretion.

"The Death of a Toad" by Richard Wilbur

A toad the power mower caught,

Chewed and clipped of a leg, with a hobbling hop has got

To the garden verge, and sanctuaried him

Under the cineraria leaves, in the shade

Of the ashen and heartshaped leaves, in a dim,

Low, and a final glade.

The rare original heartsblood goes,

Spends in the earthen hide, in the folds and wizenings, flows

In the gutters of the banked and staring eyes. He lies

As still as if he would return to stone,

And soundlessly attending, dies

Toward some deep

monotone,

Toward misted and ebullient seas

And cooling shores, toward lost Amphibia's emperies.

Day dwindles, drowning and at length is gone

In the wide and antique eyes, which still appear

To watch, across the castrate lawn,

The haggard

daylight steer.

"The Light of Other Days" by Tom Moore

Oft, in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain has bound me,

Fond Memory brings the light

Of other days around me:

The smiles, the tears

Of boyhood's years,

The words of love then spoken;

The eyes that shone,

Now dimm'd and gone,

The cheerful hearts now broken!

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain has bound me,

Sad Memory brings the light

Of other days around me.

When I remember all

The friends, so link'd together,

I've seen around me fall

Like leaves in wintry weather,

I feel like one

Who treads alone

Some banquet-hall deserted,

Whose lights are fled,

Whose garlands dead,

And all but he departed!

Thus, in the stilly night,

Ere slumber's chain has bound me.

Sad Memory brings the light

Of other days around me.

"The Unreturning" by Wilfred Owen

Suddenly night crushed out the day and hurled

Her remnants over cloud-peaks, thunder-walled.

Then fell a stillness such as harks appalled

When far-gone dead return upon the world.

There watched I for the Dead; but no ghost woke.

Each one whom Life exiled I named and called.

But they were all too far, or dumbed, or thralled,

And never one fared back to me or spoke.

Then peered the indefinite unshapen dawn

With vacant gloaming, sad as half-lit minds,

The weak-limned hour when sick men's sighs are drained.

And while I wondered on their being withdrawn,

Gagged by the smothering Wing which none unbinds,

I dreaded even a heaven with doors so chained.

"in Just-" by e. e. cummings

in Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious the little

lame baloonman

whistles far and wee

and eddieandbill come

running from marbles and

piracies and it's

spring

when the world is puddle-wonderful

the queer

old baloonman whistles

far and wee

and bettyandisbel come dancing

from hop-scotch and jump-rope and

it's

spring

and

the

goat-footed

baloonMan whistles

far

and

wee

"The Darkling Thrush" by Thomas Hardy

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter's dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land's sharp

features seemed to be

The Century's corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

"Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae" by

Ernest Dowson

"I am not as I was under the reign of the good

Cynara"—Horace

Last night, ah, yesternight, betwixt her lips and mine

There fell thy shadow, Cynara! thy breath was shed

Upon my soul between the kisses and the wine;

And I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, I was desolate and bowed my head:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

All night upon mine heart I felt her warm heart beat,

Night-long within mine arms in love and sleep she lay;

Surely the kisses of her bought red mouth were sweet;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

When I awoke and found the dawn was gray:

I have been faithful to you, Cynara! in my fashion.

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost lilies out of mind;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, all the time, because the dance was long;

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I cried for madder music and for stronger wine,

But when the feast is finished and the lamps expire,

Then falls thy shadow, Cynara! the night is thine;

And I am desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, hungry for the lips of my desire:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

"Luke Havergal" by Edward Arlington Robinson

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal,

There where the vines cling crimson on the wall,

And in the twilight wait for what will come.

The leaves will whisper there of her, and some,

Like flying words, will strike you as they fall;

But go, and if you listen, she will call.

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal—

Luke Havergal.

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies

To rift the fiery night that's in your eyes;

But there, where western glooms are gathering

The dark will end the dark, if anything:

God slays Himself with every leaf that flies,

And hell is more than half of paradise.

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies—

In eastern skies.

Out of a grave I come to tell you this,

Out of a grave I come to quench the kiss

That flames upon your forehead with a glow

That blinds you to the way that you must go.

Yes, there is yet one way to where she is,

Bitter, but one that faith may never miss.

Out of a grave I come to tell you this—

To tell you this.

There is the western gate, Luke Havergal,

There are the crimson leaves upon the wall,

Go, for the winds are tearing them away,—

Nor think to riddle the dead words they say,

Nor any more to feel them as they fall;

But go, and if you trust her she will call.

There is the western gate, Luke Havergal—

Luke Havergal.

"Cradle Song" by William Blake

Sleep, sleep, beauty bright,

Dreaming in the joys of night;

Sleep, sleep; in thy sleep

Little sorrows sit and weep.

Sweet babe, in thy face

Soft desires I can trace,

Secret joys and secret smiles,

Little pretty infant wiles.

As thy softest limbs I feel

Smiles as of the morning steal

O'er thy cheek, and o'er thy breast

Where thy little heart doth rest.

O the cunning wiles that creep

In thy little heart asleep!

When thy little heart doth wake,

Then the dreadful night shall break.

"Song" by John Donne

Go and catch a falling star,

Get with child a mandrake root,

Tell me where all past years are,

Or who cleft the devils foot;

Teach me to hear mermaids singing,

Or to keep off envy's stinging,

And find

What wind

Serves to advance an honest mind.

If thou be'st born to strange sights,

Things invisible to see,

Ride ten thousand days and nights

Till Age snow white hairs on thee;

Thou, when thou return'st wilt tell me

All strange wonders that befell thee,

And swear

No where

Lives a woman true and fair.

If thou find'st one let me know;

Such a pilgrimage were sweet.

Yet do not; I would not go,

Though at next door we might meet.

Though she were true when you met her,

And last, till you write your letter,

Yet she

Will be

False, ere I come, to two or three.

"Lullaby" by W. H. Auden

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm:

Time and fevers burn away

Individual beauty from

Thoughtful children, and the grave

Proves the child ephemeral:

But in my arms till break of day

Let the living creature lie,

Mortal, guilty, but to me

The entirely beautiful.

Soul and body have no bounds:

To lovers as they lie upon

Her tolerant enchanted slope

In their ordinary swoon,

Grave the vision Venus sends

Of supernatural sympathy,

Universal love and hope;

While an abstract insight wakes

Among the glaciers and the rocks

The hermit's carnal ecstacy.

Certainty, fidelity

On the stroke of midnight pass

Like vibrations of a bell

And fashionable madmen raise

Their pedantic boring cry:

Every farthing of the cost.

All the dreaded cards foretell.

Shall be paid, but from this night

Not a whisper, not a thought.

Not a kiss nor look be lost.

Beauty, midnight, vision dies:

Let the winds of dawn that blow

Softly round your dreaming head

Such a day of welcome show

Eye and knocking heart may bless,

Find our mortal world enough;

Noons of dryness find you fed

By the involuntary powers,

Nights of insult let you pass

Watched by every human love.

"A Noiseless Patient Spider" by Walt Whitman

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark'd where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark'd how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch'd forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form'd, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

"Full Fathom Five"

by William Shakespeare

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark! now I hear them — ding-dong, bell.

"The Windhover"

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,

in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and

striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the

hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, — the achieve of, the mastery of the

thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume,

here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a

billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: sheer plod makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

"Song" by Christina Rossetti

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

"Ozymandias" by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

"In A Station Of The Metro" by Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough .

"So We'll Go No More A-Roving" by George Gordon, Lord

Byron

So we'll go no more a-roving

So late into the night,

Though the heart be still as loving,

And the moon be still as bright.

For the sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul outwears the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

Though the night was made for loving,

And the day returns too soon,

Yet we'll go no more a-roving

By the light of the moon.

"My Heart Leaps Up When I Behold" by William Wordsworth

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

"The Sick Rose" by William Blake

O Rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm

That flies in the night

In the howling storm

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy,

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

"Upon Julia's Clothes" by Robert Herrick

Whenas in silks my Julia goes,

Then, then, methinks, how sweetly flows

The liquefaction of her clothes.

Next, when I cast mine eyes and see

That brave vibration each way free,

Oh, how that glittering taketh me!

"A Red, Red Rose" by Robert Burns

Oh my luve is like a red, red rose,

That's newly sprung in June:

Oh my luve is like the melodie,

That's sweetly play'd in tune.

As fair art thou, my bonie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a' the seas gang dry.

Till a' the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi' the sun;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

While the sands o' life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only luve!

And fare thee weel a while!

And I will come again, my luve,

Tho' it were ten thousand mile!

"Sonnet 147" by William Shakespeare

My love is as a fever, longing still

For that which longer nurseth the disease,

Feeding on that which doth preserve the ill,

The uncertain sickly appetite to please.

My reason, the physician to my love,

Angry that his prescriptions are not kept,

Hath left me, and I desperate now approve

Desire is death, which physic did except.

Past cure I am, now reason is past care,

And frantic-mad with evermore unrest.

My thoughts and my discourse as madmen's are,

At random from the truth vainly expressed,

For I have sworn thee fair, and thought

thee bright,

Who art as black as Hell, as dark as night.

"When I have fears that I may cease to be" by John Keats

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean'd my teeming brain,

Before high piled books, in charact'ry,

Hold like rich garners the full-ripen'd grain;

When I behold, upon the night's starr'd face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour!

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love!—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

"The Fountain Of Blood" by Charles Baudelaire (translated by

Rachel Hadas)

A fountain's pulsing sobs—like this my blood

Measures its flowing, so it sometimes seems.

I hear a gentle murmur as it streams;

Where the wound lies I've never understood.

Like water meadows, boulevards are flooded.

Cobblestones, crisscrossed by scarlet rills,

Are islands; creatures come and drink their fill.

Nothing in nature now remains unblooded.

I used to hope that wine could bring me ease,

Could lull asleep my deeply gnawing mind.

I was a fool: the senses clear with wine.

I looked to Love to cure my old disease.

Love led me to a thicket of IVs

Where bristling needles thirsted for each vein.

"Hope Is A Thing With Feathers" by Emily Dickinson

Hope is a thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings a tune without words

And never stops at all.

And sweetest, in the gale, is heard

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little bird

That keeps so many warm.

I’ve heard it in the chilliest land

And on the strangest sea

Yet, never, in extremity

It ask a crumb of me.

"The Convergence Of The Twain" by Thomas Hardy

Lines on the loss of the "Titanic"

In a

solitude of the sea

Deep

from human vanity,

And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she.

Steel

chambers, late the pyres

Of her

salamandrine fires,

Cold currents thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres.

Over

the mirrors meant

To

glass the opulent

The sea-worm crawls—grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent.

Jewels in joy

designed

To ravish the

sensuous mind

Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind.

Dim moon-eyed

fishes near

Gaze at the gilded

gear

And query: "What does this vaingloriousness down here?" ...

Well: while

was fashioning

This creature of

cleaving wing,

The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything

Prepared a sinister

mate

For her—so gaily

great—

A Shape of Ice, for the time far and dissociate.

And as the smart

ship grew

In stature, grace,

and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

Alien they seemed

to be;

No mortal eye could

see

The intimate welding of their later history,

Or sign that they

were bent

By paths coincident

On being anon twin halves of one august event,

Till the

Spinner of the Years

Said

"Now!" And each one hears,

And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres.

"Vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat inchohare longam" by

Ernest Dowson

"The brevity of life forbids us to entertain hopes of long

duration" —Horace

They are not long, the weeping and the laughter,

Love and desire and hate:

I think they have no portion in us after

We pass the gate.

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for a while, then closes

Within a dream.

"A Last Word" by Ernest Dowson

Let us go hence: the night is now at hand;

The day is overworn, the birds all flown;

And we have reaped the crops the gods have sown;

Despair and death; deep darkness o'er the land,

Broods like an owl; we cannot understand

Laughter or tears, for we have only known

Surpassing vanity: vain things alone

Have driven our perverse and aimless band.

Let us go hence, somewhither strange and cold,

To Hollow Lands where just men and unjust

Find end of labour, where's rest for the old,

Freedom to all from love and fear and lust.

Twine our torn hands! O pray the earth enfold

Our life-sick hearts and turn them into dust.

"Love Is Not All" by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Love is not all: It is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain,

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

and rise and sink and rise and sink again.

Love cannot fill the thickened lung with breath

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

pinned down by need and moaning for release

or nagged by want past resolution's power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It may well be. I do not think I would.

"To Celia" by Ben Jonson

Drink to me, only, with thine eyes,

And I will pledge with mine;

Or leave a kiss but in the cup,

And I'll not look for wine.

The thirst that from the soul doth rise,

Doth ask a drink divine:

But might I of Jove's nectar sup,

I would not change for thine.

I sent thee, late, a rosy wreath,

Not so much honouring thee,

As giving it a hope, that there

It could not withered be.

But thou thereon didst only breathe,

And sent'st back to me:

Since when it grows, and smells, I swear,

Not of itself, but thee.

"When I Was One-and-Twenty" by A. E. Housman

When I was one-and-twenty

I heard a wise man say,

"Give crowns and pounds and guineas

But not your heart away;

Give pearls away and rubies

But keep your fancy free."

But I was one-and-twenty,

No use to talk to me.

When I was one-and-twenty

I heard him say again,

"The heart out of the bosom

Was never given in vain;

'Tis paid with sighs a plenty

And sold for endless rue."

And I am two-and-twenty

And oh, 'tis true, 'tis true.

"To Daffodils" by Robert Herrick

Fair daffodils, we weep to see

You haste away so soon.

As yet the early-rising sun

Hath not attained his noon.

Stay, stay,

Until the hasting day

Has run

But to the even-song;

And, having prayed together, we

Will go with you along.

We have short time to stay, as you;

We have as short a spring;

As quick a growth to meet decay,

As you, or any thing.

We die.

As your hours do, and dry

Away

Like to the summer's rain;

Or as the pearls of morning's dew

Ne'er to be found again.

"Go, Lovely Rose" by Edmund Waller

Go, lovely Rose,—

Tell her that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows,

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.

Tell her that's young,

And shuns to have her graces spied,

That hadst thou sprung

In deserts where no men abide,

Thou must have uncommended died.

Small is the worth

Of beauty from the light retir'd:

Bid her come forth,

Suffer herself to be desir'd,

And not blush so to be admir'd.

Then die, that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee;

How small a part of time they share,

That are so wondrous sweet and fair.

"Afton Water" by Robert Burns

Flow gently, sweet Afton, among thy green braes,

Flow gently, I'll sing thee a song in thy praise;

My Mary's asleep by thy murmuring stream,

Flow gently, sweet Afton, disturb not her dream.

Thou stock-dove, whose echo resounds thro' the glen,

Ye wild whistling blackbirds in yon thorny den,

Thou green-crested lapwing, thy screaming forbear,

I charge you disturb not my slumbering fair.

How lofty, sweet Afton, thy neighbouring hills,

Far mark'd with the courses of clear winding rills;

There daily I wander as noon rises high,

My flocks and my Mary's sweet cot in my eye.

How pleasant thy banks and green valleys below,

Where wild in the woodlands the primroses blow;

There oft, as mild Ev'ning sweeps over the lea,

The sweet-scented birk shades my Mary and me.

Thy crystal stream, Afton, how lovely it glides,

And winds by the cot where my Mary resides,

How wanton thy waters her snowy feet lave,

As gathering sweet flowrets she stems thy clear wave.

Flow gently, sweet Afton, among thy green braes,

Flow gently, sweet river, the theme of my lays;

My Mary's asleep by thy murmuring stream,

Flow gently, sweet Afton, disturb not her dream.

"High Flight" by John Gillespie Magee

Oh, I have slipped the surly bonds of earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings.

Sunward I've climbed and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there

I've chased the shouting wind along and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long, delirious burning blue

I've topped the windswept heights with easy grace

Where never lark or even eagle flew,

And while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high, untrespassed sanctity of space

Put out my hand and touched the face of God.

"To Helen" by Edgar Allan Poe

Helen, thy beauty is to me

Like those Nicean barks of yore,

That gently, o'er a perfumed sea,

The weary, wayworn wanderer bore

To his own native shore.

On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs have brought me home

To the glory that was Greece

And the grandeur that was Rome.

Lo! in yon brilliant window-niche

How statue-like I see thee stand,

The agate lamp within thy hand!

Ah, Psyche, from the regions which

Are Holy Land!

More Romantic Poems

"Tom O' Bedlam's Song" (Anonymous Ballad, circa 1620)

"The Bustle In A House" by Emily Dickinson

"The Dark-Eyed Gentleman" by Thomas Hardy

"Directive" by Robert Frost

"Ulysses" by Lord Alfred Tennyson

"Mariana" by Lord Alfred Tennyson

"One Art" by Elizabeth Bishop

"Cirque d'Hiver" by Elizabeth Bishop

"The Fish" by Elizabeth Bishop

"The Armadillo" by Elizabeth Bishop

"the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls" by e. e.

cummings

"Methought I Saw" by John Milton

"The Send-Off" by Wilfred Owen

"Dulce Et Decorum Est" by Wilfred Owen

"Anthem For Doomed Youth" by

Wilfred Owen

"Roman Fountain" by Louise Bogan

"On the Eve of His Execution"

by Chidiock Tichborne

"No Second Troy" by William Butler Yeats

"The Balloon Of The Mind" by William Butler Yeats

"Naming of Parts" by Henry Reed

"When I Heard The Learn'd Astronomer" by Walt

Whitman

"The Listeners" by Walter De La Mare

"Exile" by Hart Crane

"Dying Speech Of An Old Philosopher" by Walter Savage Landor

"An Irish Airman Foresees His Death" by

William Butler Yeats

"Nothing Gold Can Stay" by Robert Frost

"In My Craft Or Sullen Art" by Dylan Thomas

"Dover Beach" by Matthew Arnold

"The Broken Tower" by Hart Crane

"Forgetfulness" by Hart Crane

"Interior" by Hart Crane

"Cargoes" by

John Masefield

"Aplolgia Pro Vita Sua" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

"The Garden Of Love" by William Blake

"Jerusalem" by William Blake

"London" by William Blake

"The Tyger" by William Blake

"It Is A Beauteous Evening, Calm And Free" by William

Wordsworth

"The World Is Too Much With Us" by William Wordsworth

"Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802" by

William Wordsworth

"The Fitful Alternations Of The Rain" by Percy Bysshe

Shelley

"I, Being Born a Woman, and Distressed" by Edna St. Vincent Millay

"What Lips My Lips Have Kissed" by Edna St. Vincent Millay

"Beginning My Studies" by Walt Whitman

"On My First Son" by Ben Jonson

"Those Winter Sundays" by Robert Hayden

"Cold-Blooded Creatures" by Elinor Morton Wylie

"The Mill" by Edward Arlington Robinson

"Credo" by Edward Arlington Robinson

"Here Dead Lie We Because We Did Not Choose" by A. E.

Housman

"To Brooklyn Bridge" by Hart Crane

"A Slumber Did My Spirit Steal" by William Wordsworth

"To the Moon" by Percy Bysshe Shelley

"I Knew A Woman" by Theodore Roethke

Related pages:

Romanticism Then and Now,

Romanticism Defined, The Best

Romantic Poetry, The Best Romantic

Poets, The Best Romantic Imagery, American Sapphos

The HyperTexts