The HyperTexts

The Best Protest Songs Ever

The Best Protest Poems Ever

The History of Protest Poems, Songs and Art

This is my (admittedly personal and therefore highly subjective) list of the

twenty best and most influential protest songs, poems and art. These important

works of poetic, musical and visual art are discussed in more detail later on

this page.

compiled by Michael R. Burch

The Top Twenty Protest Songs and Poems

Ding Dong! The Witch is Dead! (a song from The Wizard of Oz,

used to celebrate the death of Margaret Thatcher, England's "Iron Lady")

When Johnny Comes Marching Home (a darkly ironic anti-war folk song because

the lamenting music suggests that Johnny won't return)

Wulf and Eadwacer (an ancient Anglo Saxon poem that

movingly depicts how war causes women to be kidnapped, raped and impregnated)

Ancient Greek Epigraphs (powerful anti-war poems taken from the headstones of

fallen Greek warriors, attributed to famous Greek poets)

Anti-bullying songs like Mad World by Adam Lambert, Born This Way

by Lady Gaga and Independence Day by Martina McBride

i sing of Olaf glad and big (perhaps the ultimate anti-bullying poem,

by e. e. cummings)

Minstrel Man, Dreams and Harlem (What Happens to a Dream Deferred? (anti-racism,

anti-injustice, pro-equality poems by Langston Hughes)

Battle Hymn of the Republic (an anti-racism, anti-slavery,

anti-injustice abolitionist anthem set to the music of John Brown's Body)

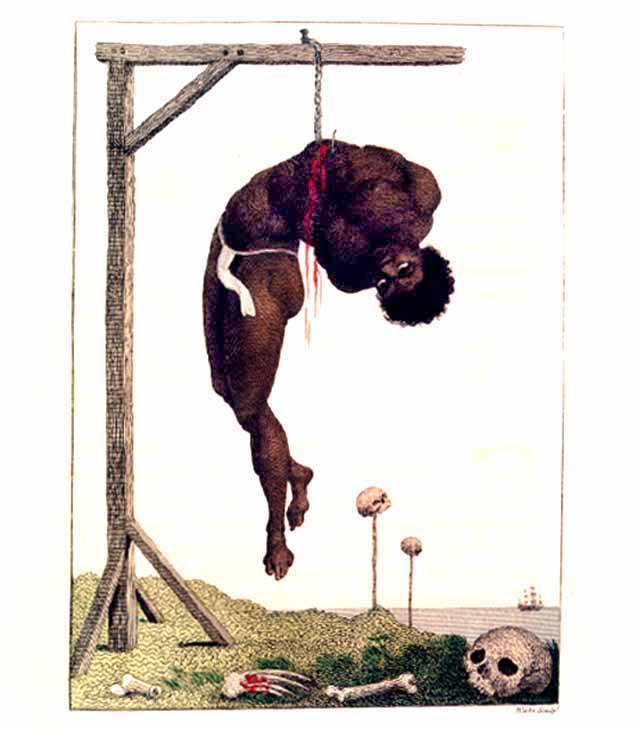

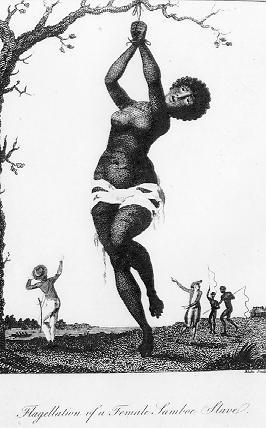

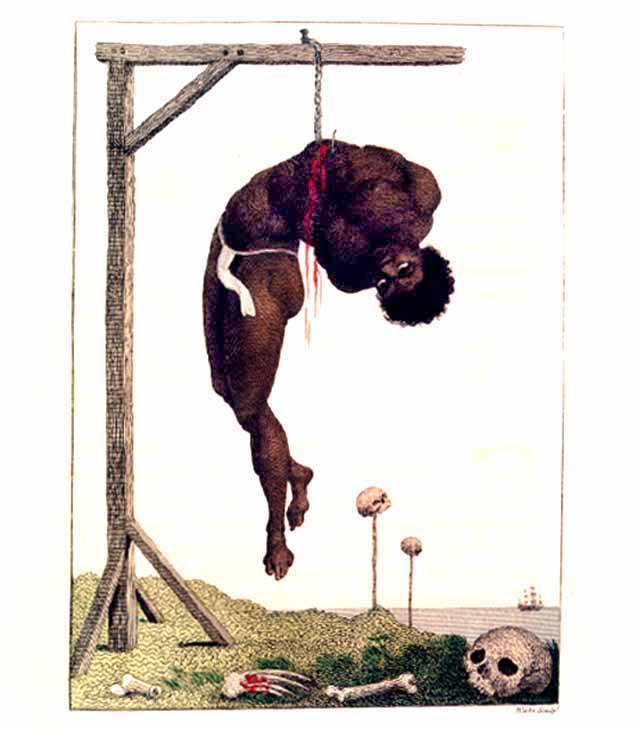

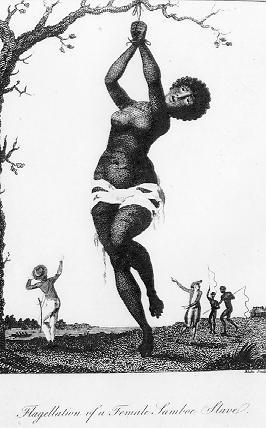

A Negro Hung Alive and Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave (anti-racism, anti-slavery visual art by William Blake)

The Little Black Boy (not just a poem against racial injustices, but a

call for unity and love between the races, by William Blake)

"All right then, I'll go to hell!" (another call to love between the races, by

Mark Twain, from a passage in Huckleberry Finn)

Howl (Alan Ginsberg's phantasmagoric, Blakean protest against the

injustices of the modern industrialized world)

Mercy Mercy Me and What's Going On (Marvin Gaye protests

damage to the earth's ecology and other injustices)

Dulce et Decorum Est (a graphic anti-war poem by the greatest of the

anti-war poets, Wilfred Owen)

Postcards 1-4 (graphic depictions of human suffering; the last

words of the greatest of the Jewish Holocaust poets, Miklós Radnóti)

Where Have All the Flowers Gone and other protest songs by American

folk singers Pete Seeger, Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell

War, Ohio, Fortunate Son, Biko, American Skin, Fuck tha Police, Allentown

and other protest songs by rockers and rappers around the world

Blowin' in the Wind (an anti-war song written and performed by Bob

Dylan)

Strange Fruit (a dark, powerfully haunting song about lynched black

bodies hanging from trees in the South, performed by Billie Holliday)

The epigrams of Sappho (the first "make love not war" poet was a woman

considered to be one of the wonders of the ancient world)

High Honorable Mention: The Hebrew prophets, "The Gettysburg Address" by Abraham

Lincoln, "Easter Hymn" by A. E. Housman, "His Confession" by the Archpoet, "The

Lie" by Sir Walter Raleigh, "London" and "Jerusalem" by William Blake, "I Have a

Dream" by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., "Imagine" by John Lennon, "A Change Is

Gonna Come" by Sam Cooke, "We Shall Overcome" written by various authors over

time, "Leaves of Grass" by Walt Whitman, "The Declaration of Independence" by

Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, "i sing of Olaf glad and big" by e. e.

cummings, "Beds Are Burning" by Midnight Oil, "I Am Woman" by Helen Reddy,

"Independence Day" by Martina McBride, "Wulf and Eadwacer," "Postcards" by

Miklós Radnóti, "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" by Oscar Wilde (who was sentenced

to hard labor for the "crime" of being gay), and the protest poems of the great

Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish

While some of my choices may seem eclectic, I think they make sense. Sir Walter

Raleigh's "The Lie" is one of first noteworthy poems to mock what we now call

"the establishment." William Blake was an English reformer cut in the poetic

mold of the Hebrew prophets. Langston Hughes spoke eloquently for African

Americans at the time they began to assert their right to equality. Martin

Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech is as much a poem as it is a sermon. Bob

Dylan and John Lennon were fans of William Blake and like Blake were not afraid

to sock it to the establishment. Sam Cooke wrote "A Change is Gonna Come" after

hearing Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind." Wilfred Owen was, in my opinion, the

greatest of the anti-war poets. Julia Ward Howe's lyrics we sung by many a Union

soldier fighting to end slavery during the Civil War. "Leaves of Grass" was Walt

Whitman's eloquent call for a freer, more tolerant America. Thomas Jefferson and

Ben Franklin were accomplished poets who wrote the opening lines of the

Declaration of Independence in ringing iambic pentameter: "We HOLD these TRUTHS

..." and it is a poem that continues to change the world, hopefully for the

better. Abraham Lincoln was another accomplished poet who wrote his own

speeches, including "The Gettysburg Address."

The top ten utopian dreams and prophetic calls to action:

Man in the Mirror (Michael Jackson's evocative, prophetic call for

social justice to begin with the individual)

Respect and I Am Woman (the ringing anthems of feminists no

longer willing to take a back seat to male chauvinists)

We Shall Overcome (an anti-racism, anti-injustice spiritual anthem

adopted by the American Civil Rights Movement)

Jerusalem (a call to peace's arms by the great anti-establishment poet William

Blake; it later became a hymn, one of my mother's favorites)

A Change is Gonna Come (Sam Cooke's wonderful, poetic response to Dylan's

Blowin' in the Wind)

Imagine (a pro-peace,

pro-tolerance, pro-brotherhood-of-man utopian spiritual anthem by John Lennon)

"If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels and have not love ..." (Saint

Paul's epiphany on ultimate, divine Love)

The Gettysburg Address (an anti-injustice call to unity written and

delivered by Abraham Lincoln, a talented poet)

"I have a dream ..." (sheer poetry by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.)

"We hold these truths to be self-evident ..." (a ringing iambic pentameter,

world-transforming poem

written by Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin, both poets)

Picking the greatest protest poems and songs of all time is, of course, very subjective, so if you disagree with my

choices, please feel free to compile your own. I will present protest poems and songs in

a roughly chronological order, in effect charting the genesis and evolution of an

important art form. I will also include some of the earliest anti-racism and

anti-slavery art, by one of the earth's earliest and greatest anti-establishment rebels, William Blake. Protest

songs didn't reach their heyday until just before the Civil War, so the early history of the genre is

more about protest poems and the rebellious poets who wrote them. But

if you read down to the mid-1800s, you can see how the protest songs of black

slaves and white abolitionists began to emerge and merge, eventually transforming American culture and

society. Those songs greatly influenced later singer-songwriters

like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, John Lennon and Bruce

Springsteen. World-changers who spoke and wrote "under the influence" of negro

spirituals included Martin Luther King Jr. and the great American protest poet

Langston Hughes.

Sappho, Fragment III (circa 620 BC)

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

Warriors on rearing chargers,

columns of infantry,

fleets of warships:

some say these are the earth's most beautiful visions;

but I say—

my beloved ...

... and I would rather see Anactoria's lively dancing and lovely face

than all the horsemen

and war-chariots of the Lydians,

or all their infantry parading in flashing armor.

Sappho may have described herself best in her own words as parthenon aduphonon, "the sweet-voiced girl."

According to Plutarch, Sappho's art was described as "sweet-voiced songs healing

love." She has been called the Tenth Muse, the Pride of Hellas, the Flower

of the Graces, the Companion of Apollo, and The Poetess. She was born on the

island of Lesbos, circa 620 BC. Her specialty was lyric poetry, so-called

because it was either recited or sung to the accompaniment of the lyre (a

harp-like instrument). "She is a mortal marvel" wrote Antipater of Sidon, before

proceeding to catalog the seven wonders of the world. Plato numbered her among

the wise. Plutarch said that the grace of her poems acted on audiences like an

enchantment, and that when he read her poems he set aside his drinking cup in

shame. Strabo called her "something wonderful," saying he knew of "no woman who

in any, even the least degree, could be compared to her for poetry." Solon so

loved one of her songs that he remarked, "I just want to learn it and die."

Sappho was so highly regarded that her face graced six different ancient coins.

But perhaps the greatest testimony to her talent is the long line of poets who

have paid homage to her, including: Plato, Plutarch, Catullus, Sir Phillip

Sidney, Ben Jonson, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

Charles Algernon Swinburne, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, A.

E. Housman, Thomas Hardy, William Butler Yeats, T. S. Eliot and William Carlos

Williams. And Sappho was for more than just a penner of love poems.

As J. B. Hare, one of her translators, said, "Sappho the poet was an innovator. At the time poetry was principally used in ceremonial

contexts, and to extoll the deeds of brave soldiers. Sappho had the audacity to use the first person in poetry and to discuss deep human

emotions, particularly the erotic, in ways that had never been approached by anyone before her. As for the military angle, in one of the

longer fragments (#3) she says: 'Some say that the fairest thing upon the dark earth is a host of horsemen, and some say a host of foot

soldiers, and others again a fleet of ships, but for me it is my beloved.' In the ancient world she was considered to be on an equal

footing with Homer, and was acclaimed as the 'tenth muse.'"

Some thoughtlessly proclaim the Muses nine;

A tenth is Lesbian Sappho, maid divine.

—Plato, translated by Lord Neaves

Today when we listen to songs by artists like Bob Dylan, John Lennon,

Michael Jackson, Madonna and Lady Gaga, who praise love and tolerance and regard

injustice, violence and war as horrors, we are hearing the poetic heirs of

Sappho, whose vision has undoubtedly triumphed over the vision of her greatest

rival, the blind, war-lauding Homer.

Ancient Greek Epitaphs (circa 582-220 BC)

Here he lies, in state tonight: great is his Monument!

Yet Ares cares not, neither does War relent.

Michael R. Burch,

after Anacreon (circa 582-485 BC)

Passerby,

tell the Spartans we lie

here, dead at their word,

obedient to their command.

Have they heard?

Do they understand?

Michael R. Burch,

after Simonides (circa 556-468 BC)

Blame not the gale, or the inhospitable sea-gulf, or friends’ tardiness,

mariner! Just man’s foolhardiness.

Michael R. Burch,

after Leonidas of Tarentum (circa 290-220 BC)

Some of the most powerful protest poems are brief inscriptions found on the tombstones of

ancient Greeks. So I created a small collection of English epigrams modeled

after epitaphs gleaned from ancient Greek gravestones and called the collection

Athenian Epitaphs.

Ancient Hebrew Protest Poetry (circa 580-520 BC)

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered

Zion.

We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.

For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that

wasted us required of us mirth, saying,

"Sing us one of the songs of Zion."

But how shall we sing the LORD's song in a strange land?

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I

prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy.

Remember, O LORD, the children of Edom in the day of Jerusalem; who said, Raze

it, raze it, even to the foundation thereof.

O daughters of Babylon, who art to be destroyed; happy shall he be, that

rewardeth thee as thou hast served us.

Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones.

The poem above makes me think of how Africans must have felt, when they were

taken into captivity, then sold as slaves to American plantation owners.

Wulf and Eadwacer (anonymous Anglo-Saxon poem, circa 960-990 AD)

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

The outlanders pursue him like crippled game.

They will kill him if he comes in force.

It is otherwise with us.

Wulf is on one island; I, on another.

That island is fast, surrounded by fens.

There are fierce men on this island.

They will kill him if he comes in force.

It is otherwise with us.

My thoughts pursued Wulf like a panting hound.

Whenever it rained and I woke, disconsolate,

the bold warrior came: he took me in his arms.

For me, there was pleasure, but its end was loathsome.

Wulf, O, my Wulf, my ache for you

has made me sick; your infrequent visits

have left me famished, but why should I eat?

Do you hear, Eadwacer? A she-wolf has borne

our wretched whelp to the woods.

One can easily sunder what never was one:

our song together.

"Wulf and Eadwacer" has been one of my favorite poems since the first time I

read it. In fact, I liked the poem so much that I ended up translating it

myself. This is one of the oldest poems in the English language, and is quite

possibly the first extant English poem by a female poet. It is also one of the

first English poems to employ a refrain. The poem's closing metaphor of a

loveless relationship being like a song in which two voices never harmonized

remains one of the strongest in any language, regardless of era. War

all-too-often separates husband from mother, and mother from child, whether by

distance or death. The poem graphically illustrates the pain and horror created

by war, and how women are often raped by the "victors," only to have the

children fathered on them taken away, or killed.

On the Eve of His Execution

by Chidiock Tichborne [1563-1586]

My prime of youth is but a frost of cares,

My feast of joy is but a dish of pain,

My crop of corn is but a field of tares,

And all my good is but vain hope of gain;

The day is past, and yet I saw no sun,

And now I live, and now my life is done ...

Tichborne's elegy to himself remains one of the best and most powerful in the

English language. He was confined to the Tower of London, then executed as one

of the many victims of England's religious wars between Catholics and

Protestants.

Declaration of Independence

by Thomas Jefferson [1743-1826]

We hold these truths to be self-evident:

that all men are created equal,

that

they are endowed by their Creator

with certain inalienable rights;

that among these are life, liberty

and the pursuit of happiness ...

This sentence, written in ringing iambic pentameter, is surely the most influential line of poetry ever written. It signaled the beginning of

the end of the rule of kings, queens and czars around the world. It would eventually deal the death-blow to slavery. Even today its basic

premise—the essential equality of all human beings, and their right to freedom and justice—continues to undergird modern

civilization. When the Bible (full of verses that command or condone racism, slavery, sexism, homophobia and religious intolerance) confronts

Jefferson's immortal sentence, human interpretations of the Bible invariably change, as more and more human beings have come to believe

that equality and tolerance are the true path to peace and happiness here on earth.

Protest poems and songs go back at least as far as the ancient Hebrew prophets,

who spoke eloquently of the need for chesed (mercy, compassion,

lovingkindness) and social justice, often in lines of stirring poetry. William

Blake, the greatest English prophet-poet, and Walt Whitman, the greatest

American prophet-poet, were students of the Bible and were no doubt

influenced by what they read. Here is one of the first great protest poems in

the modern English language:

Jerusalem

by William Blake [1757-1827]

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England's mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England's pleasant pastures seen?

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic mills?

Bring me my bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire.

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England's green and pleasant land.

William Blake proposed a new form of warfare: a

"mental fight" against the Satanic mills of what what Dwight D. Eisenhower would

later call the "military-industrial complex." His poem "Jerusalem" was

later set to music, becoming a hymn and anthem. As a matter of fact, it's one of

my mother's favorite hymns; when she found it missing from the hymnal she kept

at home, she hand-wrote it on the inside of the back cover, from memory. That's

a testament to the enduring power of William Blake's words.

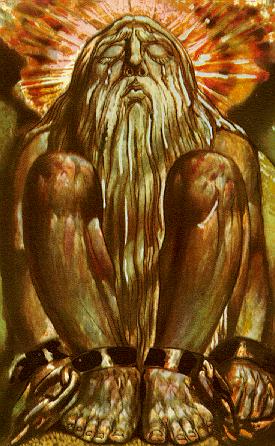

Along with Michelangelo and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Blake is one of the few great artists who were also major poets. (Examples of his

protest art appear below.) But Blake ranks higher than either Michelangelo or Rossetti as a poet, so he deserves strong consideration as the

most important poet/artist of all time. Furthermore, when his influence on modern-day poets, artists, songwriters, filmmakers, novelists,

graphic novelists, peace activists and child advocates is considered, a strong case can be made for calling Blake the most important poet

and artist of all time. After all, he was the first genius to turn poetry and art into ideological weapons to be raised defiantly

against the establishment, making him a prime mover in the arena of social change. Blake was

both the Thomas Jefferson and the George

Washington of counter-culture, anti-establishment poetry and art. He was also a poetic James Dean, the original "Rebel with a

Cause." And Blake was also a major influence on pro-peace, anti-war singer-songwriters like Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Joan Baez, Joni

Mitchell and Bruce Springsteen.

Blake was a student of the Bible, but a fierce critic of the black-robed priests of Orthodoxy who nailed THOU SHALT NOT signs above his

garden of love and earthly delights, condemning human beings to "hell" in the name of God. But today it seems that Blake has been

vindicated. The Bible published by the Roman Catholic Church, the NABRE (New American Bible Revised Edition), doesn't contain a single mention

of the word "hell." The HCSB (Holman Christian Standard Bible), published by the famously conservative and literal Southern Baptist

Convention, barely mentions "hell." If this interests you, please read why

"hell" is vanishing from the Bible. If you are interested in the subject of biblical inerrancy, please read

is the Bible infallible?

Blake's love and compassion for children are evident in his wonderfully touching

"Cradle Song." His empathy for children led him to write some of the most

moving, world-transforming protest poems of all time, after

he saw small orphaned children being forced to work long, hard, dangerous,

grueling hours in mines and factories, and as chimney sweeps:

Songs of Innocence: The Chimney Sweeper

by William Blake [1757-1827]

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry 'weep! 'weep! 'weep! 'weep!

So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep ...

Songs of Experience: The Chimney Sweeper

by William Blake [1757-1827]

A little black thing in the snow,

Crying "'weep! 'weep!" in notes of woe!

"Where are thy father and mother? Say!"

"They are both gone up to the church to pray."

"Because I was happy upon the heath,

And smiled among the winter's snow,

They clothed me in the clothes of death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe."

"And because I am happy and dance and sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God and his priest and king,

Who make up a heaven of our misery."

Blake wrote one collection of poems called Songs of Innocence and

another called Songs of Experience. The poems of the first collection

look at the world from the vantage of childish innocence, while the poems of the

second collection view the same world through the eyes of experience. In both

poems we can feel Blake's tender empathy for suffering child chimneysweeps so young they can't pronounce the "s"

in "sweep" and so can only say "weep." We can also feel Blake's anger with

religious people who go to church and "pray" while innocent children suffer and

die. What would Blake make of Jews and Christian today, who go to churches and

synagogues, and endlessly read and study the Bible, but don't know better than to allow the children of Gaza to suffer and

die so needlessly? I have no doubt that he would think as little of them as he did of the

"Christian" slavemasters who used and abused children in the "jolly old England"

of his day.

Blake was at the forefront of the British abolitionist movement, not only in

opposing slavery, but also in advocating the equality of the races, as we shall see

in the following poem (the full poem follows the plate and is much easier to

read):

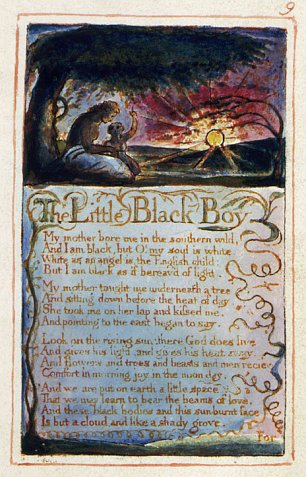

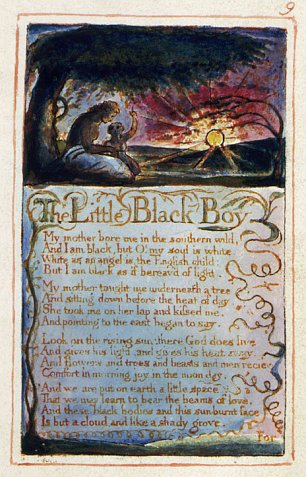

William Blake's "The Little Black Boy" (First Plate)

The Little Black Boy

by William Blake [1757-1827]

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child,

But I am black, as if bereav'd of light.

My mother taught me underneath a tree,

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east, began to say:

Look on the rising sun: there God does live,

And gives his light, and gives his heat away;

And flowers and trees and beasts and men receive

Comfort in morning, joy in the noonday.

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love;

And these black bodies and this sunburnt face

Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove.

For when our souls have learn'd the heat to bear,

The cloud will vanish; we shall hear his voice,

Saying: "Come out from the grove, my love & care,

And round my golden tent like lambs rejoice.''

Thus did my mother say, and kissed me;

And thus I say to little English boy:

When I from black and he from white cloud free,

And round the tent of God like lambs we joy,

I'll shade him from the heat, till he can bear

To lean in joy upon our father's knee;

And then I'll stand and stroke his silver hair,

And be like him, and he will then love me.

Blake also spoke clearly and forthrightly for equality between the races in his

visual art, depicting the horrors of racism and slavery more graphically than he did

any other horrors ...

William Blake's "A Negro Hung Alive"

William Blake's "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave"

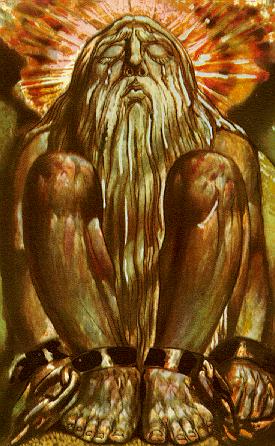

... but he seemed to go beyond that to "connect" the suffering of slaves with

the lot of suffering mankind, even poets, symbolized in the image below ...

William Blake's "Urizen in Fetters, Tears streaming from His Eyes"

Blake and other early Romantic poets including William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor

Coleridge and Robert Southey, opposed slavery. In 1796 John Gabriel Stedman, a

mercenary, published his memoirs of a five-year expedition against ex-slaves in

Surinam; his book included a number of engraved illustrations by Blake depicting

the horrifically cruel treatment of recaptured slaves. The first of these engravings has been "construed as an

explicit attack on the slave trade" because Blake depicted "the skulls of the

murdered slaves looking out over the sea to a slave ship in the distance while

the most recent victim of plantation cruelty swings on the gallows in the

foreground." These images were unique at that time for their graphic depiction of human suffering.

Stedman's book and Blake's illustrations became part of abolitionist literature.

According to the "William Blake Biography" the poet was a "prophet against empire" who opposed slavery

"over the course of his lifetime." Through his poetry and art "he was able both to counter pro-slavery propaganda

and to complicate typical abolitionist verse and sentiment with a profound and unique exploration of the effects

of enslavement and the varied processes of empire."

According to the same biography, Blake's Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793) "explores the psychologically

damaging effects of enslavement upon its victims and also caricatures the political debate over

abolition in Britain. The triangular relationship between Oothoon the female

slave, Bromion the slave-driver, and Theotormon the jealous but inhibited former

lover, depicts the sufferings of those subjugated by the trade itself and mimics

the position of the pro-slavery, vested-interest lobby and that of wavering

abolitionists [who opposed slavery in theory without strongly opposing its

actual practice] ..."

The biography concludes: "Blake was among the few British writers

who actively advocated slave rebellion and believed that it was at the edges of

empire that true revolutions would occur."

Comin Thro the Rye

by Robert Burns [1759-1796]

modern English translation by

Michael R. Burch

O, Jenny's a' weet, poor body,

Oh, Jenny's all wet, poor body,

Jenny's seldom dry;

Jenny's seldom dry;

She draigl't a' her petticoattie

She's draggin' all her petticoats

Comin thro' the rye.

Comin' through the rye.

Comin thro the rye, poor body,

Comin' through the rye, poor body,

Comin thro the rye,

Comin' through the rye.

She draigl't a'her petticoatie,

She's draggin' all her petticoats

Comin thro the rye!

Comin' through the rye.

Gin a body meet a body

Should a body meet a body

Comin thro the rye,

Comin' through the rye,

Gin a body kiss a body,

Should a body kiss a body,

Need a body cry?

Need anybody cry?

Comin thro the rye, poor body,

Comin' through the rye, poor body,

Comin thro the rye,

Comin' through the rye.

She draigl't a'her petticoatie,

She's draggin' all her petticoats

Comin thro the rye!

Comin' through the rye.

Gin a body meet a body

Should a body meet a body

Comin thro the glen,

Comin' through the glen,

Gin a body kiss a body,

Should a body kiss a body,

Need the warld ken? Need

all the world know, then?

Comin thro the rye, poor body,

Comin' through the rye, poor body,

Comin thro the rye,

Comin' through the rye.

She draigl't a'her petticoatie,

She's draggin' all her petticoats

Comin thro the rye!

Comin' through the rye.

This poem inspired the title of J. D. Salinger's novel The Catcher in the

Rye. Robert Burns was one of the first great English Romantic poets; he

wrote poems that protested social inequalities ("Is There for Honest Poverty"),

hypocritical and compassionless religion ("Holy Willie's Prayer"), etc. On the

eve of the French Revolution, he was already writing about the need for equal

rights for women. The poem above protests the way girls and women are damned by

human societies for doing what boys and men so earnestly and passionately want

them to do.

Gettysburg Address

Abraham Lincoln [1809-1865]

Four score and seven years ago

our fathers brought forth upon this continent, a new nation,

conceived in Liberty, and

dedicated to the proposition

that all men are created equal.

Make no mistake about it: Abraham Lincoln was a true poet, which you can easily

confirm by clicking here:

Abraham Lincoln, Poet.

Lincoln's greatest poem, the Gettysburg Address, contains his two great themes:

that the Union must be preserved, and that the fundamental proposition of that

Union was that all men were created equal and thus were self-evidently entitled

to Liberty (which he capitalized). That slavery was abolished and yet the Union

remains is a lasting testament to an extraordinary man who happened to be a

wonderful writer as well.

Leaves of Grass

Walt Whitman [1819-1862]

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Harold Bloom once opined that Shakespeare "invented" the

modern human consciousness. If so, Walt Whitman may have created the modern

American consciousness, or at persuaded it to become more open-minded and

tolerant.

Whitman seemed to believe that autoeroticism, homosexuality and

other things considered "evil" by church and state were, in fact, merely part of

normal human life. He invited his readers to be tolerant freethinkers and to love

freely. He was the second major poet of the "make love, not war" school, after Blake.

Because Whitman was the first major free verse poet, he was highly influential with

American and English poets to come, and with poets all around the world who

chose to break the rules of formal poetry, or at the very least greatly relax

them. No other English poet with the possible exception of Shakespeare has had

more influence on poets and poetry around the world. The fact that Whitmas was

so generous in spirit and gregarious in nature, and became so influential, has no

doubt helped many other poets, songwriters, musicians and artists become more

freethinking and tolerant themselves. In effect, he helped change the culture of

modern art.

Dover Beach

by Matthew Arnold [1822-1888]

...

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

"Dover Beach" may be the first fully modern English poem. When Arnold spoke of the "Sea of

Faith" retreating, he seemed to be setting the stage for Modernism, which to some

degree was the reaction of men who began to increasingly suspect that the

"wisdom" contained in the Bible was far from the revelation of an all-knowing God.

"All right, then, I'll go to hell!" from Huckleberry

Finn

Mark Twain [1835-1910]

So I was full of trouble,

full as I could be;

and didn't know what to do.

At last I had an idea; and I says,

I'll go and write the letter—and then see if I can pray,

Why, it was astonishing ...

[Huckleberry Finn writes a letter turning in the runaway slave Jim, in order to

save himself from going to hell for violating the law and the Bible's

injunctions for slaves to obey their masters.]

...

I took it up, and held it in my hand.

I was a-trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I

knowed it.

I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

"All right, then, I'll go to hell!"—and tore it up.

While Mark Twain wrote a few poems here and there, he is

best-known for his prose, and rightfully so. I have recast my favorite passage from

Huckleberry Finn as free verse poetry, and I believe it passes muster. This is

an important passage in American literature because the most famous American

writer makes the point that if our religion teaches us to discriminate against

our fellowmen, something is fundamentally wrong with our beliefs.

Huckleberry Finn is one of the most-read books by an American writer, and

hopefully Twain has helped convince many people to follow the example of Huckleberry

Finn, by choosing friendship, compassion and tolerance over the highly dubious "morality" preached by

narrow-minded religious types.

Early English and American Protest Songs (circa 1381 to 1837)

It has been claimed, although not proven, that English protest songs date

back to the peasants' revolt of 1381, which if true would make them the oldest

extant European protest songs. Two such candidates include "The Cutty Wren" song

and the rhyme "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?"

However, the first doesn’t show up in the written records until 400 years later,

and the latter has no known music associated with it.

Another possible candidate for the first English protest song is "The

Diggers' Song" (circa the late 17th century AD) with verses like:

But the Gentry must come down,

and the poor shall wear the crown.

Stand up now, Diggers all!

One of the earliest environmental protest songs is an 1837 musical rendition

of a poem by George Pope Morris, "Woodman, Spare That Tree!" with verses like:

That old familiar tree,

Whose glory and renown

Are spread o'er land and sea

And wouldst thou hack it down?

Woodman, forbear thy stroke!

Cut not its earth, bound ties;

Oh! spare that ag-ed oak

Now towering to the skies!

But in any case, protest music didn't really catch in a big way on until

slaves and abolitionists began turning their fear, despair and anger into

compelling songs.

Hutchinson Family Singers (1839-1846)

Perhaps the most famous early American musical voices of protest were the

Hutchinson Family Singers. From 1839 to 1846, they became well-known, singing at the White House for President John Tyler

and befriending Abraham Lincoln. Their songs touched on social issues such as

abolition, the temperance movement, politics, war and women's suffrage. Their

music was idealist and encouraged social reform, equal rights, morality,

activism and patriotism. They are generally considered to be the forerunners of

singers like Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, and are often referred to as America's

first protest band.

We Shall Overcome (circa 1853)

Charles Albert Tindley (1851-1933) was an American Methodist minister and

gospel music composer. His composition "I'll Overcome Someday" is considered to

be the basis for the U.S. Civil Rights anthem "We Shall Overcome." The song "We

Shall Overcome" was composed by artists at the Highlander Folk School in 1947:

Tindley's song had been brought to the school in the 1930s by tobacco workers

from Charleston, South Carolina. Zilphia Horton, cultural worker and educator,

taught the song at the school, where others, such as Pete Seeger and Guy Carawan,

heard it. They altered Tindley's refrain "I'll Overcome Someday" to "We Shall

Overcome" and the song was slowed down to be sung as a march hymn.

The earliest recorded use of the song "Let My People Go" was as a rallying

anthem for the Contrabands at Fort Monroe sometime before July 1862. L.C.

Lockwood, chaplain of the Contrabands, stated in the sheet music that the song

was from Virginia, dating from about 1853. The opening verse, as recorded by

Lockwood, is:

The Lord, by Moses, to Pharaoh said: Oh! let my people go.

If not, I'll smite your first-born dead—Oh! let my people go.

Oh! go down, Moses,

Away down to Egypt's land,

And tell King Pharaoh

To let my people go.

The song was made famous by Paul Robeson whose bass voice, deep and resonant,

was said by some to have attained the status of the voice of God. On February 7,

1958, the song was recorded in New York City, and sung by Louis Armstrong with

Sy Oliver's Orchestra. William Faulkner titled his novel Go Down, Moses after

a line from the song.

John Brown’s Body and Battle Hymn of the Republic (circa 1858-1861)

John Bown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

His soul goes marching on.

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

The song-poems "John Brown’s Body" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic" are

intimately related. According to David S. Reynolds, author of John Brown, Abolitionist: "No one

in American history—not even Washington or Lincoln—was recognized as much in

drama, verse and song as was Brown. One piece, the song, "John Brown's Body,"

was unique in American cultural history because of the countless transformations

and adaptations it went through."

The song known as "John Brown's Body" (originally titled "John Brown") was

first published in July of 1861, and includes the Glory Hallelujah Chorus. The

first known public performance of the song was at Fort Warren in Boston harbor

on May 12, 1861. Julia Ward Howe's more famous "Battle Hymn of the Republic" followed soon

thereafter.

"The poem, which was soon published in the Atlantic Monthly, was somewhat

praised on its appearance, but the vicissitudes of the war so engrossed public

attention that small heed was taken of literary matters. I soon was content to

know, that the poem soon found its way to the camps, as I heard from time to

time of its being sung in chorus by the soldiers."—from Reminiscences by Julia Ward Howe

The first draft of Julia Ward Howe's poem was written in November of 1861.

The first printed copy appeared in the New York Tribune on January 14, 1862. The

next month her poem was published in the Atlantic Monthly without the familiar

"Glory, Hallelujah" chorus. Atlantic Monthly editor James T.

Fields paid Howe $5 and gave her poem its now-famous title.

According to James J. Fuld’s Book of World-Famous Music: "On Nov. 27, 1858,

Brothers Will You Meet Us? was copyrighted as a separate hymn by G. S. Scofield,

New York, NY. No copy of this separate publication has been located, but it was

soon reproduced in the Dec. 1858 issue of Our Monthly Casket, published by the

Lee Avenue Sunday School, Brooklyn, vol. 1, no. 8, p. 152. The music and words

of the Glory Hallelujah Chorus are present. The opening words of the song are

"Say, brothers, will you meet us," and the song became known as a Methodist hymn

by this title. The hymn has been often credited to William Steffe but proof of

his authorship is not conclusive."

The Mormon Tabernacle Choir, one of America's most popular choruses, has made

numerous recordings of Howe's Civil War hymn, especially the 1944

arrangement by Peter J. Wilhousky, which has become the preferred one for

choruses everywhere. In the 1944 arrangement, the last verse ends with the original words:

"As He died to make men holy, Let us die to make men free."

This was changed for later Mormon Tabernacle Choir recordings to:

"As He died to make holy, Let us live to make men free."

But the word "live" does not appear in the original Julia Ward Howe version. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir had their biggest million-seller

of the song in

1959 when the 45 RPM record of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" made the pop

charts.

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot (circa 1862)

"Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" was written by Wallis Willis, a Choctaw freedman

in the old Indian Territory, some time before 1862.

Michael, Row the Boat Ashore (circa 1862)

"Michael, Row the Boat Ashore" is an African-American spiritual. It was first

noted during the American Civil War at St. Helena Island, one of the Sea Islands

of South Carolina. It was sung by former slaves whose owners had abandoned the

island before the Union navy arrived to enforce a blockade. Charles Pickard

Ware, an abolitionist and Harvard graduate who had come to supervise the

plantations on St. Helena Island from 1862 to 1865, wrote the song down in music

notation as he heard the freedmen sing it. Ware's cousin, William Francis Allen

reported in 1863 that while he rode in a boat across Station Creek, the former

slaves sang the song as they rowed. The song was first published in Slave Songs of the United States, by Allen,

Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison, in 1867.

Oh, Freedom and other early Negro Spirituals (circa 1862)

Many Negro spirituals protested slavery and oppression. Songs like "Oh,

Freedom" compared the plight of enslaved African Americans

to that of enslaved Hebrews in the Bible. Such songs antedated the Civil War.

The first collection of African-American spirituals appeared in Thomas Wentworth

Higginson's book Army Life in a Black Regiment; the songs had been collected in

1862-64, while Higginson served as a colonel of the First South Carolina

Volunteers, a regiment recruited from former slaves. Higginson was an

abolitionist, transcendentalist and an early champion of the then-unknown poet

Emily Dickinson.

I - Easter Hymn

by A. E. Housman [1859-1936]

If in that Syrian garden, ages slain,

You sleep, and know not you are dead in vain,

Nor even in dreams behold how dark and bright

Ascends in smoke and fire by day and night

The hate you died to quench and could but fan,

Sleep well and see no morning, son of man.

But if, the grave rent and the stone rolled by,

At the right hand of majesty on high

You sit, and sitting so remember yet

Your tears, your agony and bloody sweat,

Your cross and passion and the life you gave,

Bow hither out of heaven and see and save.

A. E. Housman was a non-believing homosexual ruled over by Christian philistines

who would have crucified him twice: once for his "lack of faith" and again for

his sexuality. And yet Housman seems like the better Christian, because rather

than asking to be saved personally at the expense of billions of other human

souls, he asked Jesus Christ to save everyone, if he was able. Housman's poem is

a protest against a religion that all too often preaches love while practicing

hatred, intolerance, hypocrisy and war.

XII

by A. E. Housman [1859-1936]

The laws of God, the laws of man,

He may keep that will and can;

Not I: let God and man decree

Laws for themselves and not for me;

And if my ways are not as theirs

Let them mind their own affairs.

Their deeds I judge and much condemn,

Yet when did I make laws for them? ...

Housman strongly protested the idea that Christians should be allowed to use the

Bible to create arbitrary, unnecessary laws for nonbelievers like himself. He

may have been thinking of Oscar Wilde, who was jailed on charges of

homosexuality and died shortly after his release. Why should Housman have

believed in the the highly dubious "morality" of a religion that damned him to

"jail and gallows and hell-fire" just because he preferred men to women,

sexually? This may be the first great protest poems written by a gay poet

against his Christian oppressors.

Excerpts from "More Poems," XXXVI

by A. E. Housman [1859-1936]

Here dead lie we because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

I have loved the four lines by Housman above, since I first read them. He could

write movingly without indulging in images, melodrama or sophistry, and rivals

Shakespeare in what he could accomplish with direct statement. Housman is

certainly a major poet, and one of our very best critics of human societies and

religion, along with Blake, Twain and Wilde. A good number of his poems can be

found on the Masters

page of The HyperTexts.

An Irish Airman Foresees His Death

by William Butler Yeats [1865-1939]

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan's poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

W. B. Yeats was probably the last of the great Romantics, and the first of the

great Modernists. He wrote a good number of truly great poems, and remains an

essential poet of the highest rank. "An Irish Airman Foresees His Death"

is a wonderful poem that illustrates how the people who die in war often have

little to gain and everything to lose. Yeats also wrote eloquently about how the

Irish people felt living under the thumb of imperial England. Several of Yeats' poems can be found on the

Masters page of The HyperTexts.

Directive

by Robert Frost [1874-1963]

Back out of all this now too much for us,

Back in a time made simple by the loss

Of detail, burned, dissolved, and broken off

Like graveyard marble sculpture in the weather,

There is a house that is no more a house

Upon a farm that is no more a farm

And in a town that is no more a town.

The road there, if you'll let a guide direct you

Who only has at heart your getting lost ...

...

And if you're lost enough to find yourself

By now, pull in your ladder road behind you

And put a sign up CLOSED to all but me ...

...

I have kept hidden in the instep arch

Of an old cedar at the waterside

A broken drinking goblet like the Grail

Under a spell so the wrong ones can't find it,

So can't get saved, as Saint Mark says they mustn't.

(I stole the goblet from the children's playhouse.)

Here are your waters and your watering place.

Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.

Robert Frost in "Directive" was writing about the dark load orthodox Christianity heaps on the slender shoulders of innocent

children, when it tells them that the Bible is the "infallible" and/or "inerrant" word of God, and that

human beings live in danger of eternal torment. Frost understood all too well

the emotional, psychological and spiritual damage children can suffer, when they

read verses in the Bible that say most human beings are "predestined" for

eternal damnation before they are born, and that Jesus Christ deliberately

misled most of his followers so that they could not be saved, keeping his true

teachings only for his inner circle [Mark 4:10-12]. Frost's magnificent poem is

a protest against his Christian upbringing and its "guide" who

"only has at heart your getting lost," whose followers put up signs marked "CLOSED to all but me."

I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier

Alfred Bryan (1871-1958)

World War I (1914-1918) resulted in a number of songs that protested war. One

of the most successful was "I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier" (1915) by

lyricist Alfred Bryan and composer Al Piantadosi:

Ten million soldiers to the war have gone,

Who may never return again.

Ten million mothers' hearts must break,

For the ones who died in vain.

Head bowed down in sorrow in her lonely years,

I heard a mother murmur thro' her tears:

I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier,

I brought him up to be my pride and joy,

Who dares to put a musket on his shoulder,

To shoot some other mother’s darling boy?

Let nations arbitrate their future troubles,

It’s time to lay the sword and gun away,

There’d be no war today,

If mothers all would say,

I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier ...

The Preacher and the Slave

Joe Hill (1879-1915)

American protest music from the first half of the 20th century reflected the

working classes’ struggle for fair wages and working hours. The Industrial

Workers of the World (IWW) was founded in Chicago in June 1905 and from the

start used music as a powerful form of protest. One of the most famous of the

"Wobblies" was Joe Hill, an IWW activist who traveled widely, organizing workers

and writing and singing political songs. He coined the phrase "pie in the sky,"

which appeared in his most famous protest song "The Preacher and the Slave"

(1911).

The Bourgeois Blues

Leadbelly (1888-1949)

During this period African-American blues singers were beginning to be heard

through their music, much of which protested the discrimination they faced on a

daily basis. Perhaps the most famous example of such blues protest songs is

Leadbelly's "The Bourgeois Blues," in which he sings:

The home of the Brave

The land of the Free

I don't wanna be

mistreated by no bourgeoisie.

Dulce et Decorum Est

by Wilfred Owen [1893-1918]

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime...

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

"Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" is

from Horace's Odes and means: "It is sweet and fitting

to die for one's country." This is one of the first and best

graphic anti-war poems in the English language. Wilfred Owen had a mental

breakdown during World War I, was treated, recovered, and returned to the front,

only to be killed shortly before the Armistice.

Wilfred Owen is a war poet without peer, and one of the first great modern

poets. His poem "Dulce et Decorum Est" is probably the best anti-war poem in the

English language, perhaps in any language. If man ever grows wise enough as a

species to abolish war, Wilfred Owen's voice, echoed in thousands of other poems

and songs, will have been a major catalyst.

i sing of Olaf glad and big

by e. e. cummings [1894-1962]

i sing of Olaf glad and big

whose warmest heart recoiled at war:

a conscientious object-or

his wellbelovéd colonel(trig

westpointer most succinctly bred)

took erring Olaf soon in hand;

but—though an host of overjoyed

noncoms(first knocking on the head

him)do through icy waters roll

that helplessness which others stroke

with brushes recently employed

anent this muddy toiletbowl,

while kindred intellects evoke

allegiance per blunt instruments—

Olaf(being to all intents

a corpse and wanting any rag

upon what God unto him gave)

responds,without getting annoyed

"I will not kiss your fucking flag"

straightway the silver bird looked grave

(departing hurriedly to shave)

but—though all kinds of officers

(a yearning nation's blueeyed pride)

their passive prey did kick and curse

until for wear their clarion

voices and boots were much the worse,

and egged the firstclassprivates on

his rectum wickedly to tease

by means of skilfully applied

bayonets roasted hot with heat—

Olaf(upon what were once knees)

does almost ceaselessly repeat

"there is some shit I will not eat"

our president,being of which

assertions duly notified

threw the yellowsonofabitch

into a dungeon,where he died

Christ(of His mercy infinite)

i pray to see;and Olaf,too

preponderatingly because

unless statistics lie he was

more brave than me:more blond than you.

The poem

"i sing of Olaf glad and big" denounces the brutal excesses of what

William Blake called the "Satanic Mills" and Dwight D. Eisenhower called the

"military-industrial complex." It makes a compelling case for the warmongers to

be punished, rather than the conscientious objectors.

Minstrel Man

by Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

And my throat

Is deep with song,

You did not think

I suffer after

I've held my pain

So long.

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

You do not hear

My inner cry:

Because my feet

Are gay with dancing,

You do not know

I die.

Langston Hughes was one of the most important protest poets of all time. His

poetry contained elements of traditional poetry, negro spirituals and the blues.

Strange Fruit

Lewis Allan (1903-1986)

The 1920s and 30s introduced a number of songs that protested against racial

discrimination, such as Louis Armstrong's "(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and

Blue" (1929) and the anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit" by Lewis Allan, made

famous by blues singer Billie Holliday, with verses like:

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze.

Naming of Parts

by Henry Reed [1914-1986]

"Vixi duellis nuper idoneus

Et militavi non sine glori"

Today we have naming of parts. Yesterday,

We had daily cleaning. And tomorrow morning,

We shall have what to do after firing. But today,

Today we have naming of parts. Japonica

Glistens like coral in all of the neighboring gardens,

And today we have naming of parts.

This is the lower sling swivel. And this

Is the upper sling swivel, whose use you will see

When you are given your slings. And this is the piling swivel,

Which in your case you have not got. The branches

Hold in the gardens their silent, eloquent gestures,

Which in our case we have not got.

This is the safety-catch, which is always released

With an easy flick of the thumb. And please do not let me

See anyone using his finger. You can do it quite easily

If you have any strength in your thumb. The blossoms

Are fragile and motionless, never letting anyone see

Any of them using their finger.

And this you can see is the bolt. The purpose of this

Is to open the breech, as you see. We can slide it

Rapidly backwards and forwards: we call this

Easing the spring. And rapidly backwards and forwards

The early bees are assaulting and fumbling the flowers:

They call it easing the Spring.

They call it easing the Spring: it is perfectly easy

If you have any strength in your thumb: like the bolt,

And the breech, and the cocking-piece, and the point of balance,

Which in our case we have not got; and the almond-blossom

Silent in all of the gardens and the bees going backwards and forwards,

For today we have naming of parts.

Henry Reed is likely to be remembered by this one poem, but fortunately for him

(and for us) it should make him immortal. His poem considers the irony of young

men learning the mechanisms of war during the season of love and renewal,

Spring. When I read his lovely poem, I immediately think of Pete Seeger's "Where

Have All the Flowers Gone?"

Postcard 1

by Miklós Radnóti

written August 30, 1944

translated by Michael R. Burch

Out of Bulgaria, the great wild roar of the artillery thunders,

resounds on the mountain ridges, rebounds, then ebbs into silence

while here men, beasts, wagons and imagination all steadily increase;

the road whinnies and bucks, neighing; the maned sky gallops;

and you are eternally with me, love, constant amid all the chaos,

glowing within my conscience — incandescent, intense.

Somewhere within me, dear, you abide forever —

still, motionless, mute, like an angel stunned to silence by death

or a beetle hiding in the heart of a rotting tree.

Postcard 2

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 6, 1944 near Crvenka, Serbia

translated by Michael R. Burch

A few miles away they're incinerating

the haystacks and the houses,

while squatting here on the fringe of this pleasant meadow,

the shell-shocked peasants quietly smoke their pipes.

Now, here, stepping into this still pond, the little shepherd girl

sets the silver water a-ripple

while, leaning over to drink, her flocculent sheep

seem to swim like drifting clouds ...

Postcard 3

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 24, 1944 near Mohács, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

The oxen dribble bloody spittle;

the

men pass blood in their piss.

Our stinking regiment halts, a horde of perspiring savages,

adding our aroma to death's repulsive stench.

Postcard 4

by Miklós Radnóti

his final poem, written October 31, 1944 near Szentkirályszabadja, Hungary

translated by Michael R. Burch

I toppled beside him — his body already taut,

tight as a string just before it snaps,

shot in the back of the head.

"This is how you’ll end too; just lie quietly here,"

I whispered to myself, patience blossoming from dread.

"Der springt noch auf," the voice above me jeered;

I could only dimly hear

through the congealing blood slowly sealing my ear.

IIn my opinion, Miklós Radnóti is the greatest of the Holocaust poets, and one of

the very best anti-war poets, along with Wilfred Owen and singer-songwriters

like Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and John Lennon.

I Have a Dream

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. [1929-1968]

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true

meaning of its creed:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia

the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners

will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

...

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation

where they will not be judged by the color of their skin

but by the content of their character ....

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted,

every hill and mountain shall be made low,

the rough places will be made plain,

and the crooked places will be made straight,

and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,

and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., like Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, resorted

to poetry when everything was on the line. It's ironic that today people on the

far left, such as Al Sharpton, and people on the far right, like Glen Beck, all

want to be aligned with Dr. King and his message of equality. I consider that to

be a very hopeful sign that things are improving, and will continue to improve.

Progress, after all, begins with what we consider the goal to be.

Distant light

by Walid Khazindar [1950-]

Harsh and cold

autumn holds to it our naked trees:

If only you would free, at least, the sparrows

from the tips of your fingers

and release a smile, a small smile

from the imprisoned cry I see.

Sing! Can we sing

as if we were light, hand in hand

sheltered in shade, under a strong sun?

Will you remain, this way

stoking the fire, more beautiful than necessary, and

quiet?

Darkness intensifies

and the distant light is our only consolation —

that one, which from the beginning

has, little by little, been flickering

and is now about to go out.

Come to me. Closer and closer.

I don't want to know my hand from yours.

And let's beware of sleep, lest the snow smother us.

Translated by Khaled Mattawa from the author's collections Ghuruf Ta'isha (Dar al-Fikr, Beirut, 1992) and Satwat

al-Masa (Dar Bissan, Beirut, 1996). Reprinted from Banipal No 6. Translation copyright Banipal

and translator. All rights reserved. Walid Khazindar was born in 1950 in Gaza

City. While this wonderful poem may not be a war poem, per se, the Palestinians

of Gaza have lived under an Israeli military siege and naval blockade for many

years, so I think it qualifies.

Word Made Flesh

by Ann Drysdale [birth date unknown, still living and writing]

On the broad steps of the Basilica

The feckless hopefully hold out their hands,

Often with some success; the privileged

Lighten their consciences by a few pence

On their way to receive the sacrament.

On the seventeenth step two beggars sit

Paying no regard to the worshippers

Who file past on their way to salvation.

They do not ask for alms. They are engrossed,

Skillfully masturbating one another.

Most who have noticed this pretend they haven’t;

Some of the other beggars wish they wouldn’t.

Poor relief is incumbent on the rich

And by taking things into their own hands

They spoil the scene for everybody else.

Our Lord said, “silver and gold have I none

But such as I have give I thee”. The words

Are here made flesh; with beatific sigh

One gives the other benison, slipping

All that he has into the waiting hand

Of somebody who shares his human need.

The newly shriven filter down the steps

Averting their eyes from the seventeenth,

Where the first beggar, in a state of grace,

Works selflessly towards the second coming.

This fine poem by Ann Drysdale begs the question: "What would Jesus say, and do?"

Modern Protest Songs

The 1940s and 1950s saw the continued rise of protest music that focused on

race, class and union issues. One of the most notable singers of the period was

Woody Guthrie ("This Land Is Your Land"), whose guitar bore the sticker: "This

Machine Kills Fascists." Guthrie was also an occasional member of the hugely

influential labor-movement band The Almanac Singers, founded by Millard Lampell,

Lee Hays, and Pete Seeger. Their first release in May 1941 opposed intervention

in World War II, the peacetime draft and unequal treatment of African-American

draftees. A month after it was issued, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and

Roosevelt issued an order banning racial and religious discrimination in defense

hiring. The Almanacs immediately switched to a pro-war position. Woody Guthrie

joined the group in July 1941, in time for its second album. After the Japanese

bombed Pearl Harbor in December of that year, the Almanacs issued a strongly

pro-war, pro-Roosevelt album, "Dear Mr. President." The Almanacs were widely

criticized for switching positions.

In 1948 Hays and Seeger organized a quartet initially known as the No Name

Quartet; by 1950 it was enjoying popular success as The Weavers. Several of the

Weavers’ most popular songs, such as "If I Had a Hammer," were protest songs,

although the political content was not explicit.

Paul Robeson, a black singer, actor, athlete, and civil rights activist, was

investigated by the FBI and was called before the House Un-American Activities

Committee (HUAC) for his outspoken political views. The State Department denied

Robeson a passport and issued a "stop notice" at all ports, effectively

confining him to the United States. In a symbolic act of defiance against the

travel ban, labor unions in the U.S. and Canada organized a concert at the

International Peace Arch on the border between Washington state and the Canadian

province of British Columbia on May 18, 1952. Robeson stood on the back of a

flat bed truck on the American side of the U.S.-Canada border and performed a

concert for a crowd on the Canadian side, variously estimated at between 20,000

and 40,000 people.

The 1960s was a fertile era for the genre, especially with the rise of the

Civil Rights movement, the ascendency of counterculture groups such as "hippies"

and the New Left, and the escalation of the Vietnam War.

One of the key figures of the 1960s protest movement was Bob Dylan, who

produced a number of landmark protest songs such as "Blowin' in the Wind"

(1962), "Masters of War" (1963), and "The Times They Are A-Changin'" (1964).

Dylan often sang against injustice, such as the murder of African American civil

rights activist Medgar Evers in "Only A Pawn In their Game." By 1963, Dylan and

his partner Joan Baez had become prominent in the civil rights movement, singing

together at rallies including the March on Washington where Martin Luther King,

Jr. delivered his famous "I have a dream" speech.

Pete Seeger was a major influence on Dylan and his contemporaries, and

continued to be a strong voice of protest in the 1960s, when he composed "Where

Have All the Flowers Gone" (written with Joe Hickerson) and "Turn, Turn, Turn"

(written during the 1950s but released on Seeger's 1962 album The Bitter and The

Sweet). Seeger's song "If I Had a Hammer," written with Lee Hays in 1949 in

support of the progressive movement, rose to Top Ten popularity in 1962 when it

was covered by Peter, Paul and Mary, and went on to become one of the major

anthems of the American Civil Rights movement. "We Shall Overcome," Seeger's

adaptation of an American gospel song, continues to be used by labor rights and

peace movements. Seeger was also one of the leading singers to protest President

Lyndon Johnson's policies and actions.

Other notable voices of protest from the period included Joan Baez, Phil

Ochs, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Tom Paxton. The first protest song to reach number

one in the United States was P. F. Sloan's "Eve Of Destruction," performed by

Barry McGuire in 1965.

The American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s often used Negro

spirituals as a source of protest, changing the religious lyrics to suit the

political mood of the time. The use of religious music helped to emphasize the

peaceful nature of the protest. Some such songs were carried across the country

by the Freedom Riders and became Civil Rights anthems, including Sam Cooke’s "A

Change Is Gonna Come" and Otis Redding’s "Respect," made famous by Aretha

Franklin. The white music scene of the time also produced a number of songs

protesting racial discrimination, including Janis Ian's "Society's Child," a

1966 song about an interracial romance forbidden by a girl's mother and frowned

upon by her peers and teachers.

In the 1960s and early 1970s many protest songs condemned Vietnam War,

including "Simple Song of Freedom" by Bobby Darin (1969), "I Ain't Marching

Anymore" by Phil Ochs (1965), "Lyndon Johnson Told The Nation" by Tom Paxton

(1965), "Bring Them Home" by Pete Seeger (1966), "One Tin Soldier" by Original

Caste (1969), and "Fortunate Son" by Creedence Clearwater Revival (1969). Woody

Guthrie's son Arlo Guthrie also wrote one of the decade's most famous protest

songs in the form of the 18-minute-long talking blues song "Alice's Restaurant

Massacree," a satirical protest against the draft.

As their fame and prestige increased in the late 1960s, The Beatles — John

Lennon in particular — added their voices to the Anti-war movement. The song

"Revolution" (1968) commemorated worldwide student uprisings. In 1969, when

Lennon and Yoko Ono were married, they staged a week-long "bed-in for peace" in

the Amsterdam Hilton, attracting worldwide media coverage. At the second

"Bed-in" in Montreal, in June 1969, they recorded "Give Peace a Chance" in their

hotel room. The song was sung by over half a million demonstrators in

Washington, D.C. at the second Vietnam Moratorium Day, on October 15, 1969. In

1972 Lennon's controversial protest song "Woman Is the Nigger of the World" set

off a storm of controversy, and in consequence received little airplay and much

banning. The Lennons went to great lengths to explain that they had used the

word "nigger" in a symbolic sense and not as an affront to African-Americans.

The U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State shootings of May 4, 1970

amplified anti-war sentiment and protest songs about The Vietnam War continued

to grow in popularity and frequency, including Chicago's "It Better End Soon"

(1970), "War" (1969) by Edwin Starr, and "[Four Dead in] Ohio" (1970) by Crosby,

Stills, Nash, and Young. Another notable anti-war song of the time was Stevie

Wonder's frank condemnation of Richard Nixon's Vietnam policies in his 1974 song

"You Haven't Done Nothin'."

While war continued to dominate the protest songs of the early 70s, other

issues were also addressed. Helen Reddy's feminist hit "I Am Woman" (1972)

became an anthem for the women's liberation movement. Bob Dylan also made a

brief return to the genre with "Hurricane" (1976), which protested the

imprisonment of Rubin "Hurricane" Carter as a result of racism and profiling,

which according to Dylan led to a false trial and conviction.

In the early 70s soul music became one of the strongest voices of protest in

American music, led by Marvin Gaye's seminal 1971 protest album "What's Going

On", which included "Inner City Blues," "Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)" and the

title track.

In the 80s the Reagan administration was attacked for its policies, in Bruce

Springsteen's "Born in the U.S.A." (1984), and "My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down"

by The Ramones. Billy Joel's "Allentown" protested the decline of the rust belt,

and represented people coping with the demise of American manufacturing. A

number of songs were written to protest of Iran-Contra scandal, including "All

She Wants to Do Is Dance" (1984) by Don Henley.

In Jamaica, the ravages of poverty and racism and the birth of reggae music

led to Bob Marley's famous "Redemption Song," recorded shortly before his

premature death in 1981.

The 1980s also saw the rise of rap and hip-hop, and with it bands such as

Grandmaster Flash ("The Message"), Boogie Down Productions ("Stop the

Violence"), "N.W.A ("Fuck tha Police") and Public Enemy ("Fight the Power")

which vehemently protested the discrimination and poverty which the black

community faced in America, in particular focusing on police discrimination and

brutality.

Punk music continued to be a strong voice of protest in the 1980s; the most

notable protest song is Patti Smith's 1988 recording "People Have the Power."

Rage Against the Machine, formed in 1991, has been one of the most popular

'social-commentary' bands of the last 20 years. A fusion of the musical styles

and lyrical themes of punk, hip-hop, and thrash, Rage Against the Machine railed

against corporate America ("No Shelter", "Bullet in the Head"), government

oppression ("Killing in the Name"), and Imperialism ("Sleep Now in the Fire",

"Bulls on Parade"). The band used its music as a vehicle for social activism

because, as lead singer Zack de la Rocha said, "Music has the power to cross

borders, to break military sieges and to establish real dialogue."

The '90s also saw a huge movement of pro-women's rights protest songs from

most musical genres as part of the Third-wave feminism movement. Ani DiFranco

was at the forefront of this movement, protesting sexism, sexual abuse,

homophobia, racism, poverty, and war. Her "Lost Woman Song" (1990) asserts that

a woman has a right to choose an abortion without being judged. A particularly

prevalent movement of the time was the underground feminist punk Riot Grrrl

movement, including a number of outspoken protest bands such as Bikini Kill,

Bratmobile, Jack Off Jill, Excuse 17, Heavens to Betsy, Huggy Bear,

Sleater-Kinney, and also lesbian queercore bands such as Team Dresch. Sonic

Youth's "Swimsuit Issue" (1992) protested the way women are objectified and

shilled by the media.

After the '90s, the protest song found renewed popularity around the world as

a result of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars in the Middle East, with America's

former president George W. Bush facing the majority of the criticism. Many

famous protest singers of yesteryear, such as Neil Young, Patti Smith, Tom

Waits, and Bruce Springsteen returned to the public eye with new anti-war

protest songs. Young approached the theme with his song, "Let's Impeach the

President," a stinging rebuke of George W. Bush and the War in Iraq. Smith wrote

two new songs indicting American and Israeli foreign policy: "Qana," about the

Israeli airstrike on the Lebanese village of Qana, and "Without Chains," about

the U.S. detention center at Guantanamo Bay.

R.E.M., who had been known for their politically charged material in the

1980s, also returned to increasingly political subject matter. For example,

"Final Straw" (2003) is a politically-charged song. The song was written as a

protest of the U.S. government's actions in the Iraq War.

In "The Day After Tomorrow," Tom Waits adopts the persona of a soldier

writing home that he is disillusioned with war and thankful to be leaving. The

song does not mention the Iraq war specifically, and, as Tom Moon writes, "it

could be the voice of a Civil War soldier singing a lonesome late-night dirge."

Waits himself does describe the song as something of an "elliptical" protest

song about the Iraqi invasion, however. Thom Jurek describes "The Day After

Tomorrow" as "one of the most insightful and understated anti-war songs to have

been written in decades. It contains not a hint of banality or sentiment in its

folksy articulation." Waits' recent output has not only addressed the Iraqi war,

as his "Road To Peace" deals explicitly with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

and the Middle East in general.

Bruce Springsteen has also been vocal in his condemnation of the Bush

government, among other issues of social commentary. In 2000 he released

"American Skin (41 Shots)" about tensions between immigrants in America and the

police force, and of the police shooting of Amadou Diallo in particular. For

singing about this event, albeit without mentioning Diallo's name, Springsteen