At Least, Save Children by Fidia95

Darfur (Jesus Wept)

by William F. DeVault

Half a million dead in Darfur, in the Sudan.

100 times the innocents who died on 9/11.

Children. Women. Men. Genocide.

Wake up and see.

Wake up and see.

Wake up and see why

Jesus wept.

The rains didn't come

the sounds of the drums

the death knell kept.

Jesus wept.

Over the burning sands

the killing commands

of the warlords swept.

Jesus wept.

It should be true

that the evils evil men do

we cannot accept.

Jesus wept.

The slaughter rained on

as in the blistering dawn

the sun, the horizon, leapt.

Jesus wept.

Half a million women and children and sons and daughters

fall to the hate, their fate as wormfood for the slaughters.

Since when are 100 black babies worth less than one white businessman

in the eyes and lies of people who claim to be, to see, without sin?

Wake up and see.

Wake up and see.

Wake up and see why

Jesus wept.

Copyright by William F. DeVault; all rights reserved. You can

hear William F. DeVault perform "Darfur (Jesus Wept)" with his band, The

Gods of Love, by clicking

here.

You Who Read No Calm

by T. Merrill

You, who read no calm reportings

Of alien, distant, dire events,

But shriek and keen as loves go down

Beyond all help, to violence;

Whose temple's walls, stormstruck and split

By sizzling bolts collapse around,

While mid the crash of chaos hope

Whirls in a death-spin to the ground;

You, who alone in deep distress

Cry out for help where there is none,

All you whom I shall never know:

I know a portion nonetheless

Of cruel trials you undergo.

Killers in many guises come:

Sudden as electric shock

Or looming ghostly as a shark

Leisurely finning toward its mark.

I who breathless and sweating once

Wrestled a devil to the floor,

And saw him rise again when he

Finished what he began before,

I who re-learned each childhood prayer

Forgotten, to the stars once more

Send up a poor and hopeless plea

For spirit's peace beyond despair.

Tears of Darfur

by Mahnaz Badihian

O tired land

O depressed sky of Darfur

O plain of no breath

You are bleeding from all corners

Of your dreams

The bosom of your land

Weeps the bitterness of blood

O tearful Darfur,

Can your hungry hands

One day cultivate those

Dry, sad roots, left from

The countless bones

Of your children

Can your simple dreams

Of having a

Loaf of bread and a roof above

Come through?

Maybe,

Maybe one day

Those broken wings

Will heal

With the caressing hands

Of peace

We the people of the world

With our tearful eyes

Waiting on the day that

Acacias will bloom

On the lands where

The dream of innocence pours

On these hopeless days

War Metaphysics for a Sudanese Girl

Adrie Kusserow

I leave the camp, unable to breathe,

me Freud girl, after her interior,

she Lost Girl, after my purse,

her face:

dark as eggplant,

her gaze:

unpinnable, untraceable,

floating, open, defying the gravity

I was told keeps pain in place.

Maybe trauma doesn't harden,

packed, tight as sediment at the bottom of her psyche,

dry and cracked as the desert she crossed,

maybe memory doesn't stalk her

with its bulging eyes.

Once inside the body

does war move up or down,

maybe the body pisses it out,

maybe it dissipates, like sweat and fog

under the heat of a colonial God,

and in America, maybe it flavors dull muzungu lives,

each refugee a bouillon cube of horror.

Maybe war can't be soaked up

by humans alone,

the way the rains in Sudan

move across the land,

drenching the ground, animals, camps, sky,

no end to its roaming

until further out, among the planets,

a stubborn galaxy finally mops it up,

and it sits, hushed,

red, sober,

and below, the humans in the north

with their penchant for denial,

naming it aurora borealis.

*Muzungu means "white person" in many Bantu languages of east, central and

South Africa

Milk

Adrie Kusserow

Sudanese Refugee Camp, Northwest Uganda

I.

Our drivers gun insanely over the dusty, red roads,

lurching from pothole to pothole.

Caravan of slick, adrenalized vans,

tattooed with symbols of western aid,

Will on my lap, trying to nurse between bumps,

my hands a helmet to his bobbing skull.

A three-legged goat hobbles to the side

and though we imagine we are a huge interruption,

women balancing jeri cans on their heads, face our wake

of dust and rage as they would any other gust of wind—

Water, sun, NGO.

We arrive covered in orange dust, coughing,

fleet of SUVs parked under the trees,

engines cooling, Star Trekkian cockpits flashing,

alarms beeping and squawking as we zip-lock them up

and leave them black-windowed, self-contained as UFO's.

Behind the gate, we stumble through the boiling, shoulder deep sun,

Will and I trying to play soccer

as a trickle of Sudanese kids cross the road

hanging against the fence, watching the chubby Muzungu boy

I've toted around Africa like a pot of gold.

Three years old, he knows they're watching, so he does a little

dance,

his SpiderMan shoes lighting up as he kicks the ball.

II.

Part African bush, part Wild West,

we're based in Arua, grungy, dusty frontiertown,

giant dieseled trucks barrel through, spreading their wake of

adrenalin,

obese sacks of grain lying like walrus inside.

I chase Will from malarial puddle to puddle,

white blouse frilled like a gaudy gladiola,

lavish concern for my chubby son

suddenly rococo, absurd.

III.

7 foot giants of the SPLA, huddle together, drinking,

talking Dinka politics, repatriation, the New Sudan,

wives lanky as giraffes, set food on the table and disappear.

In candlelight the men's forehead scars gleam—

I flutter around them acting more deferential than I'm used to,

slowly I'm learning Sudanese grammar—

men, verbs, women, the conjunctions that link them together.

In the thick of rain we walk home,

Ugandans huddled under their makeshift bird cages,

Will now pointing to the basic vocabulary of this road—

dead snake, prickly bush, squealing pig, peeing child.

Three drunk men huddled at a shack

scrape the whiteness off us as we walk by.

Though I don't want to hear it,

though I love Africa,

it starts up anyway, the milky mother cells of my body high-fiving,

my mind quietly repeating the story of my son's lucky birth,

his rich American inheritance.

IV.

My husband drops into bed, dragging a thick cloak of requests.

All day, I've labored behind him, toting our clueless muzungu,

watching him, dogged Dutchman in his rubber clogs

climbing the soggy hills of Kampala, despite the noonday heat,

a posse of hopeful Lost Boys following him.

He, afraid of nothing, really; not even death,

me afraid of everything really, most of all his death.

In the distance, trucks rev up to cross the bush

where Sudanese families perched like kites caught in trees,

wait for the next shipment.

But it's night now,

the three of us inside the cloud chamber of our mosquito net,

the two of them breathing, safe.

Will's nursing again, though he doesn't need to,

swelling like a tick

and though I don't want to love

the sweet mists of our tiny tent home,

the lush wetlands of our lives,

its thick rope bridges and gentle Ugandan hills,

the fat claw of my heart rises up,

fertile, lucky, random

pulsing its victory song.

Mud

Adrie Kusserow

I.

The pond black and bulging,

ice storm ruins poking from the water

like the stiff feet of, dare I say, fallen soldiers.

Robert still in Sudan,

back in Vermont, the kids and I limp through two weeks of cold rain,

I drape Ana and Will in rain gear

watch the drunken tents run across the field.

Ana plunks her chubby toes into a fleet of tadpoles

cold mud sucking her foot into its mouth.

I drag the branches onto shore,

globs of frog eggs surface like transparent brains,

Ana cupping the dimpled jelly,

the dogs licking it like caviar.

Entranced, she squeezes it

until I tell her to stop

before she crushes the eggs.

I tell myself it's not quite violence but over eager love,

this lust with which they squeeze the living,

smearing the mud onto their own limbs.

But what of this blur

between awe and destruction,

love and violence?

At night, the peepers,

screaming themselves into existence.

Two frogs griplocked onto a female,

her flesh bulging between their swollen fingers.

"They're wrestling," I say, not wanting to reveal the darker side of their

mating.

I gingerly pry the males off, Will cheering,

Ana serious and methodic

until she finally dislodges the last one's grip with her twig

and they fall apart wriggling in the grass.

II.

The rains just started in Juba, south Sudan,

making travel, and maybe war, near impossible.

Still my husband pushes a saggy jeep for eight hours

through four feet of mud, a Sudanese boy

lying unconscious in the back seat.

The jeep rocking and lurching

on the only road cleared of mines

as my husband tries to inch it forward, this, his own labor of love,

like birth, like sex, something always tears,

his foot jammed with a thorn as he heaves and sinks

his toenail tearing off, until even he gives up

and forces them to turn back,

still 40 miles from Aliab, the whole village waiting for them,

caught in an outbreak of cholera,

its one river littered with rusty ammunition,

trucks large as elephants lying on their sides.

When Abraham, their Lost Boy,* came home after 18 years,

the elders sacrificed a white cow.

Jump over it, into peace, they cried

while the women tipped their thin necks back,

their whips of ululation uncoiling in the heat.

III.

The frogs, still wiggling on the grass,

Ana clutches the tan-pink female,

despite its eerie mask, she wants to take it home.

I tell her just one night,

then we'll let it go back to its real home—

but the next morning it's done the impossible,

jumped out of its three foot fortress.

I roam the rooms crazed, desperate to find it.

I do,

a day later, shrunken in the comer of the bathroom

but still breathing. I race it to the pond,

children confused behind me,

watch it sink, stunned, then lethargically swim away,

still dried and wrinkled, despite its immersion in water,

like Abraham, now more American than Sudanese,

sitting wide-eyed and stiff amidst the wailing and singing.

IV.

Robert home, worn out, but safe.

I take a walk to the pond and find—

a tan-pink frog, perhaps the same one,

floating in the water,

I can't tell if it's alive or dead.

I know how I came to be married to this man,

I followed him from country to country,

gripped him hard as the frogs—

Still he did not peel me off, as I have tried to do

with his over eager love, for this gangly, barren country of Sudan.

Who knows what will be torn next,

it's just what happens when you love the world

and you move blindly, but well intentioned,

amidst the irresistible mud.

*The "Lost Boys" refers to the 17,000 children in southern Sudan

who fled

their homes in 1987 seeking refuge from the civil war. They walked 1,000 miles

before they finally found protection in a Kenyan refugee camp, Kaukuma. By the

time they arrived there, half of the boys had died from starvation, thirst,

soldiers, lions and bandits. About 3,700 have recently been resettled in

America.

Darfur

by Michael R. Burch

Darfur,

I admit that my heart recoils

from the thought of your agony

as the hammering machine guns

yammer at your ebony

breast.

Darfur,

I am not equal to the task

of your impassioned soliloquy.

Darfur, I am pressed

hard to understand

why men molest

innocence

so violently.

Darfur, I confess—

I have watched you dying

silently.

Darfur, I would bless

you,

if only I knew

how.

Darfur,

I stand helpless,

naked before your indignation

now.

Darfur,

I have only my pen.

Let me wield it like a rapier,

set fire to this paper,

till the world in burning shreds

collapses on our heads

and we see your fate is ours

if we cannot change the course

of this world intent to maim

each man who’s not the "same"

in color and in creed.

And yet the blood you bleed,

as red as mine, demands

that we die holding hands.

O Darfur,

I’ll bleed too

when the ravenous jackals

are through

with you.

a Passover reflection, April 2006

Who knows one? One is the

Janjaweed militia cleansing Darfur

Who knows one? Two is the

stealing and killing of livestock

Who knows one? Three is the

poisoning of wells and the destruction of crops

Who knows one? Four is the

use of rape to destroy and humiliate families

Who knows one? Five is the

creation of two-and-a-half million people: displaced, hungry, susceptible to

disease

Who knows one? Six is the

over four hundred thousand people who have already died.

These and more are the

plagues of Darfur.

Who knows one?

I know one.

Send a postcard to President

Bush. Urge him to take leadership on this issue.

lo dayenu — but it is not

enough.

Who knows one?

I know one.

Encourage institutions to

hang Save Darfur banners outside their buildings.

lo dayenu — but it is not

enough.

Who knows one?

I know one.

Attend the rally in

Washington, DC on April 30th.

lo dayenu — but it is not

enough.

Who knows one?

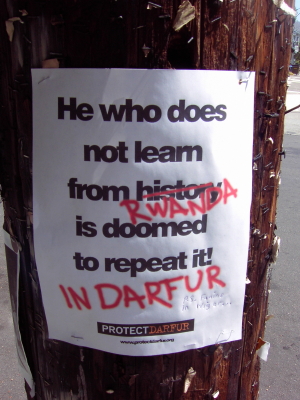

I know one — Rwanda

Who knows one?

I know one — Bosnia

Who knows one?

I know one — Cambodia

There are too many ones.

And I am the child who does

not know how to count:

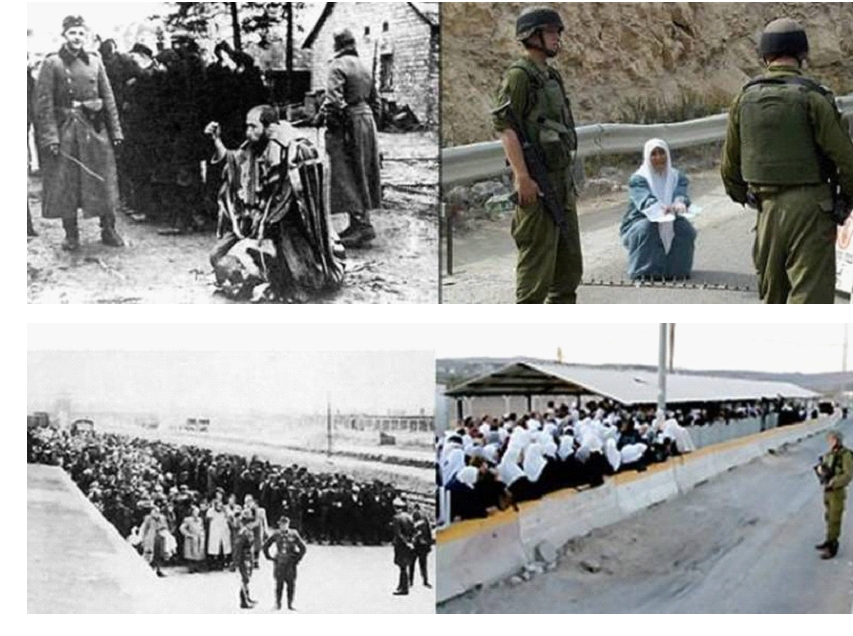

One. Two. Four hundred

thousand. Six million.

For six million are the lips

of our dead mouthing “never again” in eternal silence.

Who knows one? I know one.

For I am that one.

One person created in the

image of God.

It is for me alone to speak

out. I and no other.

Not a messenger, not a

congressperson, not a president.

I alone am here to tell the

tale.

Who knows one? I am that one.

And who knows — I may be the

one who will make the difference.

On the Propensity of the Human Species to Repeat Error

by Christina Pacosz

"And if they

kill others for being who they are

or where they are

Is this a law of history

or simply, what must change?"

—Adrienne

Rich

The world is round.

This should tell us

something, this should

have been our first clue

what goes around

comes around

Scientists are studying

a rent in the roof of sky

over the South Pole

right now but poets

need not adhere

to the caution

of the scientific method.

The message is simple:

what goes around

comes around

The battery acid of

Plato's Republic

has finally reached

the ozone layer,

a membrane, protective

like skin or an amniotic sac,

permeable and destructible

what we take

for granted

will get us

in the end

The Sioux woman's breast

severed from her body

dried into a pouch

for tobacco,

what book was that?

Or a chosen people's skin

stretched across the heavens,

shade for us to more easily

read the harsh lesson

of history.

I am a woman

by Sheema

Kalbasi with Roger Humes

I am woman

coming from the desert

coming from the long line of tribes

coming from the long line of faiths

They called me mad

They chained me to the wall naked

yet I broke free the bonds

and ran through the pain of my existence

in search of the innocence that was denied me

and they called me mad

and they called me the evil spawn of Satan

yet I broke free the bonds

and ran towards our freedom

where I knelt

before the Mother and the Son

and I called them Salvation

and they named me Nation

and I tore loose the chains of captivity

only to fall once more into bondage

when I was raped by a Mongol

married a Jew

gave birth to a Muslim

watched the child convert to Buddhism

watched the child marry a Bahai

live as a Christian

die as a Hindu

I am a woman

I am the river

I am the sky

I am the clouded covered trees upon the mountain

I am the fertile earth whose song the plants drink deep

I am the long line of tribes

I am the long line of faiths

Don't try to convert me

into something I am not

for I am already all

that humanity will ever be

The Blade of Grass in a Dreamless Field

by

Takashi "Thomas" Tanemori

Only a few knew it existed;

No one knew its power;

The world would never be the same again,

Changing irrevocably and forever.

The six-hundred-year history of Hiroshima

Disappeared in the ashes,

On this Judgment Day, on this Morning!

(i)

Blameless souls forever vanish

on this morning, this judgment day.

Our silent cries, to heaven we appeal,

scattered like the ash of withered leaves.

Our ebbing souls

cling to that lonely sky;

we try in vain to escape this sea of flame.

Oh, Hiroshima, once my haven,

why has your life been sacrificed?

(ii)

The abounding sadness within my heart . . .

drowning my loneliness in tears of self-pity.

Four abandoned children;

wishing to feel our mother's love,

just once more;

if only in our dreams.

The heat of yet another long night lingers.

Oh, Hiroshima, once my home,

my tears run dry waiting for the breaking dawn.

(iii)

My soul is torn by this rage inside,

an orphan of war;

why does this make me feel guilty?

Why do my neighbors turn away

or, close their ears when I speak?

Bitterness poisons this innocent child,

I madly waste away.

Oh, Hiroshima, once my cradle,

I am waiting to die.

(iv)

Gathering remnants of my courage,

I stand alone in this notorious America, land of the enemy.

An outcast with slanted eyes,

I fall before the indifference of strangers;

sightlessly, they trample upon my dignity.

This life of anguish seems to be my destiny.

Praying for death, I endure time.

Oh, Hiroshima, once my comfort,

I am lost in dreams of revenge.

(v)

Budding leaves renew this tired place, this tired soul;

gently the rain is embraced by your love,

comforting this savaged heart.

A blade of grass emerges from the ashes,

and my heart becomes a light,

connecting me to heaven.

Living for one another, this is my path!

Oh Hiroshima, forever my love,

may my life become a bridge from you and others.

(vi)

At the dawn of the 21st century,

we honor this passage through darkness.

We must have the courage to enter

the void again . . . and again,

emerging with the gift of new life.

Healing only comes through learning to forgive

and making peace with our past.

Only then, will the wind whisper:

"Hibakusha, you have not lived in vain!"

Crisis (Darfur)

by lungelo mbatha

Won’t you help to sing the song of Bob Marley

If ‘tis all we seem to have!

For how long shall they kill our PEOPLE

Genocide after genocide

Whilst everybody stands and looks …

When shall the Children taste the fruit

From the freedom tree watered at its root

By the blood of our people before us

Oh! What a shame on the ‘body of nations’!

Jumping from left to right, round and round

Wasting time, when ever The Burnt Faces are at the receiving end!

Let that old black fist of AMANDLA rise up high

Now open to make it STOP, to make it STOP!

A Child of the Millennium

by Charles Adés

Fishman

He’s five months old now — a little short

on experience — but if he could speak,

Jake would sit with the Dalai Lama on a red

and golden throne and hold forth on happiness

and compassion on freeing the mind from vengeance

and regret and living in exile from the sacred home:

he’s seen the end of days . . . and the beginning.

He doesn’t know about race or gender

or that we are murdering the planet that the earth

is smoldering with underground fires and with the bone-

fires of hatred He doesn’t know about ethnicity

or religion and will not take with him into the new century

memories of calcined corpses or an interior landscape

peopled with napalmed children.

What Jake is best at has nothing to do with genocide

or the acid tides of history He travels in realms

where tenderness is a face that brushes his face

He feels the strength of those around him and their love

and time ticks at his wrist like the gentlest rain His eyes

are the most translucent lakes, his smiles tiny suns

that shine a clear light on the living.

Children of The Holocaust

by Joseph McDonough

The perfectly white

cat

sits upon

the lush green lawn

they run they run

through fields

of sun

calling calling its name

Ashes Ashes

falling

like rain

Poets Against the Genocide in Dafur

by

Gordon Ramel

Nobody knows how many people have died during

the two-year conflict in Sudan's western Darfur region.

US academic Eric Reeves estimated the death toll at

340,000 at the beginning of 2005.

But so far the crisis shows no signs of abating.

from

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3496731.stm

If a poet’s true vocation is to speak

with words so well perfected they remain

as thoughts forever in the hearer’s brain,

then poets are the people we must seek.To spin bright webs that will ignite the minds

and wake the sleeping masses of this world,

‘til they become a tidal wave that’s hurled

against the cruel indifference that blinds

the tame and tepid leaders of our time.

The systematic slaughter in Dafur,

this gory, gruesome, genocidal war,

is now our world’s most sick and senseless crime;

and I for one would like my government

to make its end their primary intent.

Black Climate of Change

by Zyskandar Jaimot

gone into giant swirling whirlwinds of khamseens

gone into vicious sprawling outbursts of tribal revenge

mothers, babes all bundled together in refuge

mothers calling, praying to strange foreign deities for succor

their voices unheeded in all the world

their DNA gone – vanished amid waves of bloody sand

never replaced – never thought of – never considered

their DNA unimportant

their DNA inconsequential

their essence gone

The HyperTexts