its 6,000 hilarious rhyming lines

about a mouse's struggle to escape

the sewer into which he was born,

forlorn,

and yet able to make

your jaw drop, agape:

The Mouse Whole

an epic poem

by

Richard Moore

Listen to Richard Moore's reading

of Book 1 of The Mouse Whole

Listen to Richard Moore's reading

of Book 2 of The Mouse Whole

Listen to Richard Moore's reading

of Book 3 of The Mouse Whole

Listen to Richard Moore's reading

of Book 4 of The Mouse Whole

Listen to Richard Moore's reading

of Book 5 of The Mouse Whole

More Work by Richard Moore:

The

Self: A Consideration (essay)

Pain and Death

(essay)

How I Blew It At The New Yorker (essay)

THT's First Interview with Richard Moore (interview with THT editor Mike

Burch)

THT's Second Interview with Richard Moore (interview with THT editor

Mike Burch)

Poetic Meter in English: Roots and Possibilities (essay)

On Rhyme

(essay)

The

Balancer: Yeats and His Supernatural System (essay)

A Fair's End (poetry) can be

read online at the New Formalist Press website.

Grants

Government and the arts, alas, they just don't mix.

Your bed of roses, bureaucrat, is full of pricks.

Ménage á Deux: Songs for a Father-to-be

She's pregnant, none more beautiful than she.

Inside her we can feel

the future stirring; outside we can see

darkly the storm birds wheel.

Like Berkeley's God, I labor constantly

to keep this frail world real.

No little tendrils of the heart

bind strong enough when little ruptures start;

people who live together learn to live apart.

"Can't you be someone else once in a while?"

My question starts her smile.

She gives her head a toss and calmly eyes me:

"Why don't you fantasize me?

But come to think of it," her look grows steady,

"that's what you do already."

The year's darkness, the miracle of birth,

animal me, my worth

as calculated in the drift of stars,

prices of prunes, sports cars...

O stuff all that! Where is the world that she

dreamt of, now wants to see?

Let's go again!

—upon all fours.

Let's close our houses up, live out of doors,

we, destined to become extinct as dinosaurs.

Technology keeps going faster,

its future still unfolding, ever vaster.

Earth cries, Human intelligence

—what a disaster!

But no, the tent's folded, no longer sunned in

the hills of France and Spain,

where streams flow night and day, a campsite one din

from which we can refrain,

stuffed into winter countryside, from London

two easy hours by train.

I see nothing

—yes, nothing right

there in the afternoon, already night,

its faces all aglow with false electric light;

and I remember unreality

first flooding into me,

washing my mother's earnest luncheon word

into the vast absurd.

I took it with me back to boarding school,

she gone then, I its tool.

The only real question was when

I would go mad, marching with Caesar's men.

Look now: I'm laboring at Latin once again.

She lay in dimness with the candle lit,

back bare, me rubbing it.

Some words, now lost, went between me and her,

and then it seemed there were

no words, nothing to touch or hold in store,

between us any more.

Day after day, she wakes, she feeds

both of them. O, memento of our deeds

there, always there, a tiresome queer shape with needs

—

she says, "Things that I think I'll say sound dumb,

so I don't say them. True

enough, but they'd sound silly. So I strum

the guitar, sing....I'll do

differently soon, my dear; soon I'll become

sullen and closed like you."

Then quietly, no sigh, no moan:

"I see I'm to have this baby alone.

You are a killer, Dick." And thus a seed is sown.

"Don't let me kill you!" frantically I plead.

She laughs, from her mood freed,

"I feel better already. You don't moan.

You just wander alone

and only get more gloomy and morose."

The seed! I hold it close

—

managed, however, from that soil to dig me

my image of the Pygmy,

suggesting life more magical and mythic

in the late Paleolithic.

I've put all that into another book.

Interested, Reader?...Look!

'N editor I'm to see, upon

my word, a London literary don,

my critical hairs combed, int'lectu'l necktie on.

The lies we live by subtly consume us.

Bury us, then, in humus

since we were human. Read, Reader, appalled,

but don't blame that on me!

The deepest lie we tell is the lie called

sentimentality,

and of its forms the worst is facile gloom,

the automatic rages

like mine that kill all feeling....Let love bloom!

How deeply it engages

when the immortal Schubert, magic rager,

modulates into major!

The publisher is in his house;

winds will not blow him, nor will downpours douse.

He knows he mustn't publish 'n epic 'bout a mouse.

If things aren't getting better (now the rage)

then in some golden age

(sometimes I would be "I," but mostly "it")

all unfit things would fit,

all categories blend and cease their clamor.

That puts an end to grammar,

and frees me, doesn't it? I'll dance about,

let all my feelings out,

living in holiness and simple awe, per-

haps actually a pauper

and not just faking it, concealing wealth

to cheat National Health.

We got the whole damn baby free:

hospital, doctor, nurse, dispensary....

(procedures and their names change when you cross the sea.)

How long did Adam, Eve, gardening peons,

live before falling? Eons!

The Stone-Age hunters whom my spirit craves,

living in draughty caves,

changed not once in a hundred thousand years

the way they tipped their spears.

Had they no passions to be vented,

to keep on going on like that, contented,

free of our mania for change, as though demented?

Each week

—habit from which I cannot budge

—

I cook a pound of fudge.

The emptiness of life demands that filler.

It is my sweetness-pillar

huge for me there: catlike I made and fenced it

and rub myself against it.

Conrad, black male, is huge, to see

on windowsills, but hard to capture. He

(God knows how he lives) fills woods with his progeny.

Surrounded by the bored and boring Brits

in pubs sad Richard sits.

They, for whom everything has happened, wait

for one more twist of fate,

which creeps, alas now, slower than molasses.

Time still to fill their glasses.

Open to misery, distress,

I, female, give it

—palpable!

—access.

It enters, comes. I'm left pregnant with hopelessness.

The winding road, the clipped and tonsured earth:

a woman's giving birth.

Warm pulpy beings, clever, know so much

impossible to touch;

masters of concepts difficult to name,

they will rot just the same.

Wives come to help out, fuss and fix,

cheap tongues for advertising's vulgar tricks.

There are no peasants left nowadays, only hicks.

God, will I spoil it for her, home today,

forget, say, what to say?

Lose my poor wits in fits and mindless fretting?

She stands there, "It's like getting

a doll for Christmas, Dick

—that's what I feel

—

except this doll is real."

Where with this wild child may my way be?

I, no one...do I feel...jealousy maybe

of my heroic wife? Come on! Let's kill the baby.

In the sharp bathroom light that hardly flattered,

her face looked ravaged, shattered.

She seemed to come apart, seemed toothy, spiky,

the sweet calm in her psyche

usurped, canceled by brute power within,

the new stranger, our kin.

My story ends, the future hid.

I, all my rubbish still under its lid,

never went mad. O God! She in that crib there did.

Published in Edge City Review

When In Rome...

There was once a fat diner named Schlurp.

After dinner he'd noisily burp.

Said his wife, "Go and dine a

few decades in China,

where everyone does that, you twerp!"

Published in Light Quarterly

Yet Another Apology

Why's he so cutting, ironic, unkind,

like those bitter old pagans of Greece?

"A positive mind is a turbulent mind."

My negative mind is at peace.

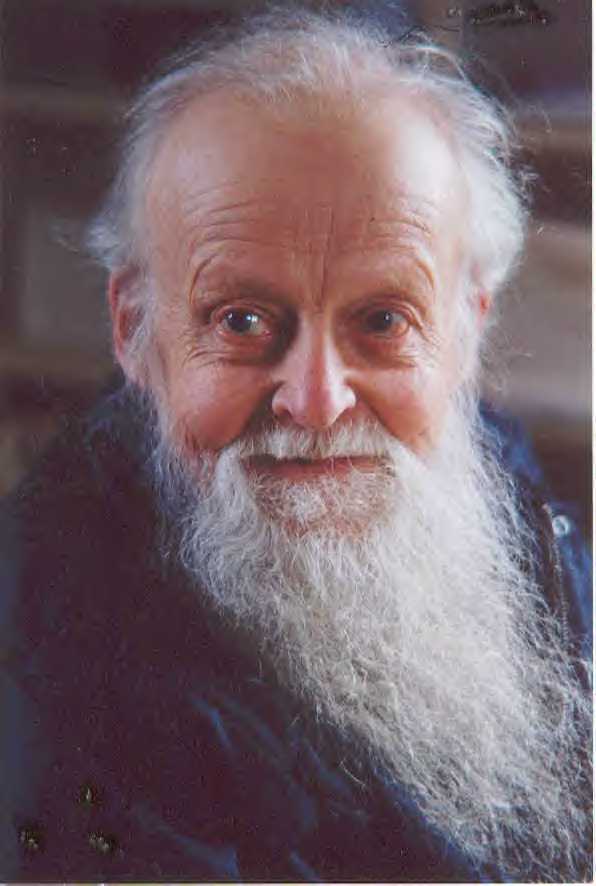

Of Richard Moore's ten published volumes of poetry, one was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and another was a T.

S. Eliot Prize finalist. He also authored a novel,

The Investigator

(Story Line Press, 1991), a collection of essays,

The Rule That Liberates

(University of South Dakota Press, 1994), and translations of Plautus' Captivi

(in the Johns Hopkins University

Complete Roman Drama in Translation

series, 1995) and Euripedes' Hippolytus (in the

Penn Greek Drama Series,

U. of Pennsylvania, 1998). Moore's poetry books include

The Mouse

Whole: An Epic (Negative Capability Press, 1996),

Pygmies and Pyramids

(Orchises Press, 1998) and

The Naked Scarecrow (Truman State University Press, New Odyssey Editions, 2000). He

was listed in

Who's Who In America, and articles

on his work have appeared in

The Dictionary Of Literary Biography and

numerous newspapers and journals. His fiction, essays, and more than 500

of his poems, were published in a great variety of magazines, including

The

New Yorker, Atlantic, Harper's, Poetry, The American Poetry Review, and

The

Nation. He also published translations of poetry in German,

French, and Italian. During his life he gave frequent readings, lectures and dramatic

performances in Boston, Washington, and other cities.

Moore taught at Boston University, Brandeis University, the New England

Conservatory of Music, and Clark University. He led the Agape poetry series in

Boston and The Poetry Exchange in Cambridge, Mass. and Leesburg, Va.

Richard Wilbur had this to say about Moore's seventh collection of poems,

Bottom

Is Back, Orchises Press, 1994: "The best and most serious poetry

is full of gaiety, and it is only dreary poets and their too-earnest readers who

consider light verse demeaning. X. J. Kennedy is right to remind us, in

his prefatory poem, that funny and satiric poets will dine at journey's end with

the likes of Byron, Bierce, and Landor. In any case, if the reader will

look at such a delightful and flawless poem as Richard Moore's "In Praise

of Old Wives," the question of light verse's legitimacy will become

academic.

Nine of Richard Moore's books may be

ordered from the bookstore of

Expansive Poetry & Music

Online, which also has pretty pictures of them. All 14 of his books can be ordered from

Moore's web

site, where there are descriptions of each book. His books are also available on

Amazon.com, but there they are mixed up with

the books of numerous other Richard Moores, a name almost as common as John Smith.

His poetry book

A Fair's End

can be read online for free, at the New Formalist Press website.

More Epigrams and Philosophy of Richard Moore:

Here is a more extensive collection of the thoughts of

Richard Moore on poetry, physics, psyche-ologoy, etc. (a smaller collection appeared

earlier on this page).

Logic, like Rilke's angel, is beautiful but dangerous.

The social animal—at least, in the human case—is necessarily an imitative

animal; for it would seem to be our capacity to imitate others and to let their

thoughts and personalities invade ours that makes coherent society possible.

We descendants of Christianity,

we creations of that book, The Bible, can't endure Lucretius' lush relish and

appreciation of the sensuous life here on earth. Everything in our abstract,

celluloid-charmed, computer-driven, and, above all, money-maddened lifestyle

separates us from that life on earth.

Christians, humanists, existentialists—whatever we are—we gaze toward higher, or

at least more interesting things.

[The] constant of uncertainty—'Planck's constant'—is a very important number in

physics and makes its appearance in many experiments and theories. It has been

grandly called 'the quantum of the cosmos;' but its full title should be 'the

quantum of whimsicality of the cosmos.' Thus, in its ultimate detail the cosmos

is unpredictable, and this is so because we affect the cosmos by looking at it,

that is, because the observer and what he observes cannot be separated. The

metaphor, the myth, of separation between the subjective observer and objective

reality has broken down. There is no observer, no observed. There is only

experience.. . . in any intense experience the self vanishes. It only

enters later as a social and linguistic convenience when there is talk about the

experience. It arises, not from experience as a whole, but from language—our

human language of the last few dozen millennia—in particular.

So I relax—or try to, trying to forget the useless conceptions I have been

taught—and let myself change minute by minute. Glitter of sunlight and great

shadows pass over the landscape. If I exist at all, I am like music, forever

modulating into new keys.

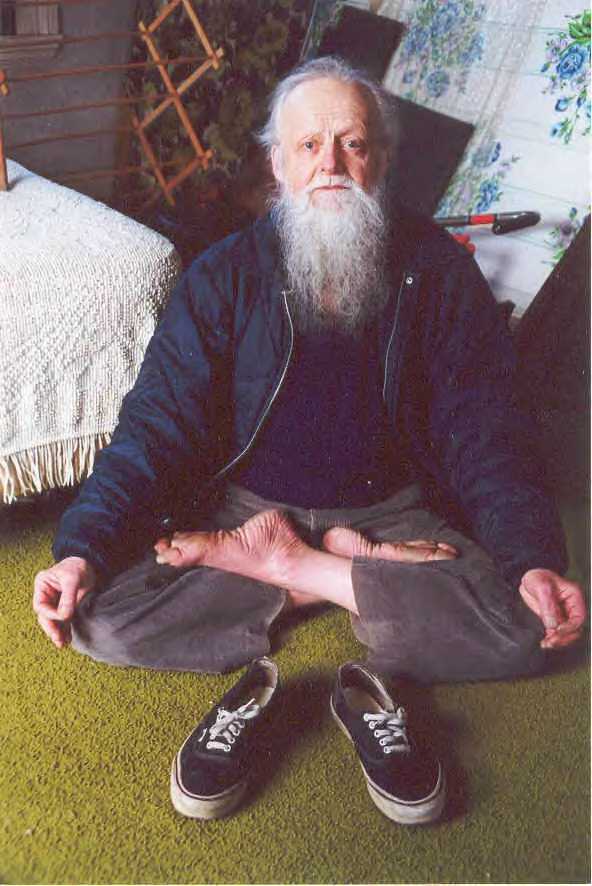

Sometimes when I can leave off for a while the actions and thoughts which keep

defining a self for me unawares, I sit still and feel that nothing—feel it as

something positive, something mysteriously, actually there. The zero, the real

person, the central being. That which will slip and slide outside of any

definition, any set of actions, any work of art even. This central person, this

true self, will never be found. We deal with it every day.

Government and the arts, alas, they just don't mix.

Your bed of roses, bureaucrat, is full of pricks.

The poet writes for himself as the other.

Poetry deepens and expands on

the reality we share which makes us social.

There's a wildness in poetry—especially when it rhymes.

Let us have more wildness, more madness, in poetry; let us have more rhyming!

No two poets rhyme exactly alike.

. . . what I love best is humor and horror happening at once . . .

I am very concerned that the new formalism will revert to the old stodginess.

I think the public has good reasons for its lack of interest [in contemporary

poetry].

Metaphor is the soul of poetry, and the essence of metaphor is resemblance; so

the poet, throwing away his Immanuel Kant, cries out that resemblance is the

source of all categories. (And a theorem or two in higher algebra will bear him

out.)

Read other poets, poets! Relish their rhymes and do likewise. Your own private

rhyming dictionary will form in the depths of your soul and deliver you into

eternity."

Rhyming, done correctly, clarifies the difference between responsible philosophy

and irresponsible poetry. The philosopher writes what he thinks; the poet

discovers what he thinks when he writes: he is borne (perhaps I mean born) into

what he believes by the rhyme, the rhythm, the eloquence of what he is saying.

Rhymes are always local. They belong to the nitty-gritty specificity (try saying

that phrase out loud, Reader!) of the language. They are almost impossible to

translate.

. . . the greatest poetry has always been local. International poetry is

like the English spoken at the U. N. Everyone understands it, and it means next

to nothing. So let us leave the Great World Cities to their raging proletariats

and hope that somewhere in the boring boondocks something bold and gutsy is

stirring, something alive with subtle rhythms and wild rhymes.

Art thrives on difficulty. The audience (if there is one) delights when the

poet, like the impossible archer, hits the mark. What effortless grace! Such

deeds seem beyond human skill. He must be a god.

It is a terrible limitation on poets, just to write about poets. How are other people

going to be interested in their poems?

When I read Homer, I sometimes

have the feeling that we have been starving to death for 3000 years. It is a

terrible limitation on poets, just to write about poets. How are other people

going to be interested in their poems?

Jacob Brownowski said that atomic physics has been the great poem of the

twentieth century. Good to know that there has been one! It's curious how, as

poets and their work fall into near total disrepute, that word "poem" still

retains its mystical aura, so that even scientists rush to label themselves with

it in public.

Poems have to be genuine performances—by which I mean: I'm not going to

please others ultimately unless I please myself, and, ditto, I am not going

to please myself ultimately unless I please someone else too.

One [i.e., the poet] has to take risks, as the capitalists say, and I have

staked my life—as we all must—on my hunches. Emily Dickinson did that with

incredible resolve and courage. She's my hero at the moment. She imagined a

reasonable person to write for, and she stuck to it. Pleasing that person

was the only way to please herself.

Poets like Milton or Hopkins who use complicated language usually have simple,

familiar ideas to express; poets like Swift who have shocking, complex ideas

usually express them in the simplest possible language. I love Swift. [Younger

poets, and older poets too, should take note of the word "love" here, since

Richard Moore didn't use words loosely.]

My mouse [the hero of

The Mouse Whole] modeled his epic on Dante:

that darling, that pet of the age, / with professors for every page.

I wonder how many unindoctrinated "common men" actually read Whitman. I ran a

little Whitman experiment once. I had been reading quite extensively in the

works of that canny, tough-minded politician, Abraham Lincoln. After I had

finished reliving—perhaps I mean, redying—his assassination, I thought it might

be interesting to imagine that I was Lincoln's ghost, reading Whitman's famous

elegy on me, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd."

What dreadful,

verbose, sentimental rubbish is this? cried the author of the Second

Inaugural Address. Personally I am an admirer of that elegy and was shocked to

hear Lincoln's ghost say that, but there is no accounting sometimes for the

tastes of statesmen and politicians. And your Mr Everyman, poptune lover, of the

present time will never like listening to Whitman. Whitman's poems don't

rhyme.

It's amazing what modern arts audiences nowadays will put up with. What a

little pretentiousness won't do! The Parisians in its first audience threw

rotten vegetables at Stravinsky's

Rites of Spring. Now in Ann Arbor,

Michigan, everybody politely sits, pretending to enjoy it. [This reminds us of

one the very best, and most hilarious, books on modern art and literature: Tom

Wolfe's

The Painted Word.]

Years ago, when I taught a class in poetry writing in Brandeis University,

the students had never heard of me, but they all knew about John Ashbery and

knew how great he was, though none of them could explain why.

Tributes by Other Poets

More or Less

by Michael R. Burch

for Richard Moore

Less is more —

in a dress, I suppose,

and in intimate clothes

like crotchless hose.

But now Moore is less

due to death’s subtraction

and I must confess:

I hate such redaction!

The HyperTexts