The HyperTexts

Richard Moore, Poet: Tribute and Memorial

Richard Thomas Moore was a poet, performer, novelist, essayist, teacher, philosopher,

mathematician and scholar―and one of the foremost

writers of his era.

Richard Moore was born on September 25, 1927, in Connecticut and died on November 8, 2009

in Cambridge, Massachusetts, close to his home in Belmont. Richard will be sorely missed, although his words will remain with

us as long as the English language endures.

A poet should be known primarily by his own words, not other people's opinions of them, so if you haven't read

Richard Moore's poems and essays, please begin by investigating the links immediately below, then return to this page

and scroll down to read what his contemporaries have to say about the man, the writer, and

his work. This page will be updated as new tributes and memorials are received,

so please bookmark it and visit as often as you can. For a writer there can be

no greater tribute than for his words to be read, and re-read. After all, that's

how writers become immortal. We suggest that readers new to Richard Moore's work

begin with his main THT poetry page, then "work their way down." His epic poem

"The Mouse Whole" is autobiographical, more or less, and can give readers

insight into the man and his other writings, but it will take some time to

devour, due to its length. The second link for "The Mouse Whole" contains

recordings of Richard reciting the poem himself.

Richard Moore (his main THT poetry page)

A Life (his last essay)

The

Self: A Consideration (essay)

Pain and Death

(essay)

The Mouse Whole (his

epic poem)

Listen to The Mouse Whole

(the spoken word version)

How I Blew It At The New Yorker (essay)

THT's First Interview with Richard Moore (interview with THT editor Mike

Burch)

THT's Second Interview with Richard Moore (interview with THT editor

Mike Burch)

Poetic Meter in English: Roots and Possibilities (essay)

On Rhyme

(essay)

The

Balancer: Yeats and His Supernatural System (essay)

A Fair's End (poetry) can be

read online at the New Formalist Press website.

His personal website.

Hi, Mike,

I looked on your Richard Moore memorial page for his poem “The Cyclist’s Psych

List” (from Sailing to Oblivion), but didn’t find it. Its last lines constitute

a good epitaph:

… Like good King Wenzel,

I wrote my life in pencil

and never feared its end.

When it appeared, my friend,

I reached out and embraced it;

then God kindly erased it.

To that I wrote (and sent to him) a reply which you might also like to include

as a tribute:

Some fear a life in pencil

when death has drawn them hence’ll

be soon erased; and ink

may fade before you blink.

But Richard Moore can neuter

death with a small computer.

We know if he is on it or

not by th’ eternal monitor.

It is his happy Schicksal

to be saved pixel by pixel.

I came across all this while combing through old computer files and thought that

if anyone would care to preserve it, it would be you.

All best,

Jan Schreiber

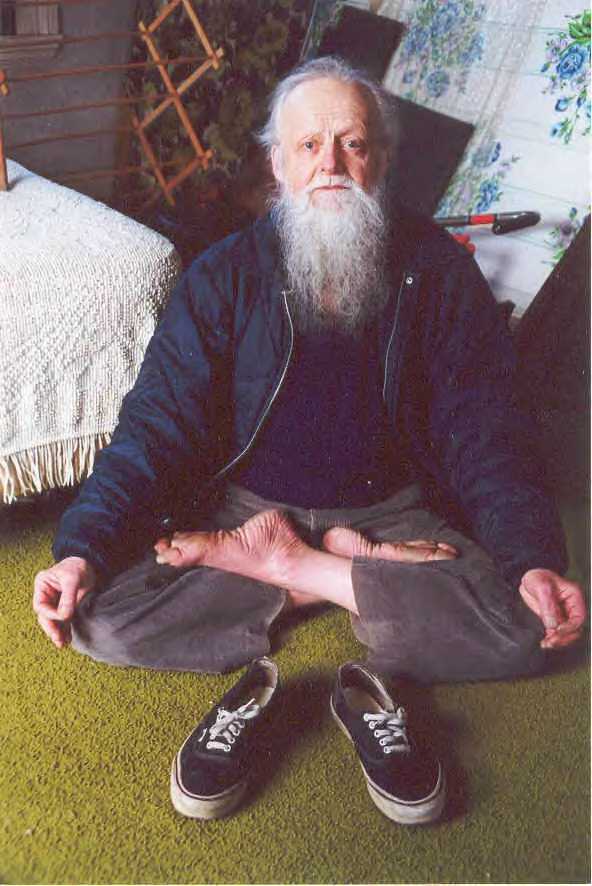

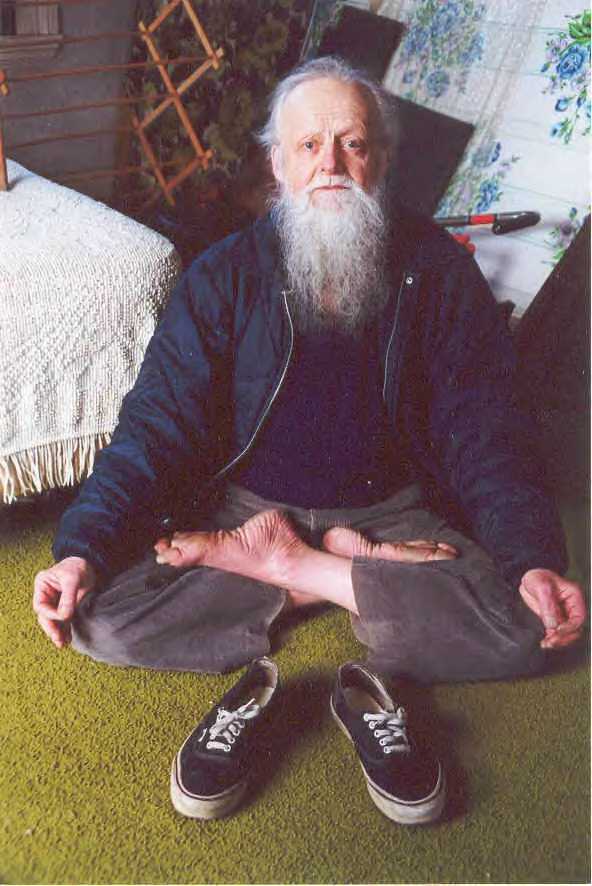

A Yogi Sees The Light

That lady has learned Hebrew, gung-

ho to greet God in His own tongue.

And I? I'm one whom God will notice

because I'm sitting in the lotus.

Silly! A God who deems it fitting

to see me won't care how I'm sitting.

Published in Light Quarterly

Richard Moore Quotations:

"The poet writes for himself as the other."

"We all think of poetry as speech that is

somehow special, striking, memorable. We want to remember, not just the idea, as

with prose, but the actual words that utter it.

Sound effects like rhythm and rhyme are the easiest, most recognizable ways to

accomplish this."

"Poems have to be genuine

performances—by which I mean: I'm not going to please others ultimately unless I

please myself, and, ditto, I am not going to please myself ultimately unless I

please someone else too."

"One [i.e., the poet] has to take risks, as the capitalists say, and I have

staked my life—as we all must—on my hunches. Emily Dickinson did that with

incredible resolve and courage. She's my hero at the moment. She imagined a

reasonable person to write for, and she stuck to it. Pleasing that person was

the only way to please herself."

"Poets like Milton or Hopkins who use complicated language usually have simple,

familiar ideas to express; poets like Swift who have shocking, complex ideas

usually express them in the simplest possible language. I love Swift." [Younger

poets, and older poets too, should take note of the word "love" here, since

Richard Moore didn't use words loosely.]

"My mouse [the hero of The Mouse Whole] modeled his epic on Dante: that

darling, that pet of the age, / with professors for every page."

"I wonder how many unindoctrinated "common men" actually read Whitman. I ran a

little Whitman experiment once. I had been reading quite extensively in the

works of that canny, tough-minded politician, Abraham Lincoln. After I had

finished reliving—perhaps I mean, redying—his assassination, I thought it might

be interesting to imagine that I was Lincoln's ghost, reading Whitman's famous

elegy on me, 'When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd.' What dreadful,

verbose, sentimental rubbish is this? cried the author of the Second

Inaugural Address. Personally I am an admirer of that elegy and was shocked to

hear Lincoln's ghost say that, but there is no accounting sometimes for the

tastes of statesmen and politicians. And your Mr Everyman, poptune lover, of the

present time will never like listening to Whitman. Whitman's poems don't rhyme."

"It's amazing what modern arts audiences nowadays will put up with. What a

little pretentiousness won't do! The Parisians in its first audience threw

rotten vegetables at Stravinsky's Rites of Spring. Now in Ann Arbor,

Michigan, everybody politely sits, pretending to enjoy it." [This reminds us of

one the very best, and most hilarious, books on modern art and literature: Tom

Wolfe's The Painted Word.]

"Years ago, when I taught a class in poetry writing in Brandeis University, the

students had never heard of me, but they all knew about John Ashbery and knew

how great he was, though none of them could explain why."

"The poet in me has learned, as

the poet, Keats, learned and described, that the only way to write something

wonderful is to find a way to have it write itself."

"Poetry deepens and expands on the reality we share which makes us social."

"Metaphor is the soul of poetry, and the essence of metaphor is resemblance; so

the poet, throwing away his Immanuel Kant, cries out that resemblance is the

source of all categories. (And a theorem or two in higher algebra will bear him

out.)"

"There's a wildness in poetry—especially when it rhymes."

"Read other poets, poets! Relish their rhymes and do likewise. Your own private

rhyming dictionary will form in the depths of your soul and deliver you into

eternity."

"No two poets rhyme exactly alike."

"Rhyming, done correctly, clarifies the difference between responsible

philosophy and irresponsible poetry. The philosopher writes what he thinks; the

poet discovers what he thinks when he writes: he is borne (perhaps I mean born)

into what he believes by the rhyme, the rhythm, the eloquence of what he is

saying."

"Rhymes are always local. They belong to the nitty-gritty specificity (try

saying that phrase out loud, Reader!) of the language. They are almost

impossible to translate."

" . . . the greatest poetry has always been local. International poetry is like

the English spoken at the U. N. Everyone understands it, and it means next to

nothing. So let us leave the Great World Cities to their raging proletariats and

hope that somewhere in the boring boondocks something bold and gutsy is

stirring, something alive with subtle rhythms and wild rhymes."

"Let us have more wildness, more madness, in poetry; let us have more rhyming!"

"Art thrives on difficulty. The audience (if there is one) delights when the

poet, like the impossible archer, hits the mark. What effortless grace! Such

deeds seem beyond human skill. He must be a god."

"I am very concerned that the new formalism will revert to the old stodginess."

"There is an association, it seems, between formality of verse and formality of

attitude which I think is quite false. Certain formalist magazines are very

timid about what they will allow in tone and subject matter. If there are people

to lose, you are certainly going to lose them that way."

"It is a terrible limitation on poets, just to write about poets. How are other people

going to be interested in their poems?"

"I think the public has good reasons for its lack of interest [in contemporary

poetry]."

"Government and the arts, alas, they just don't mix.

Your bed of roses, bureaucrat, is full of pricks."

"When I read Homer, I sometimes

have the feeling that we have been starving to death for 3000 years."

"Jacob Brownowski said that atomic physics has been the great poem of the

twentieth century. Good to know that there has been one! It's curious how, as

poets and their work fall into near total disrepute, that word "poem" still

retains its mystical aura, so that even scientists rush to label themselves with

it in public."

"For any artist, the doing of

the thing is its own fulfillment. After that, recognition is nothing."

The social animal—at least, in the human case—is necessarily an imitative

animal; for it would seem to be our capacity to imitate others and to let their

thoughts and personalities invade ours that makes coherent society possible.

"We descendants of Christianity,

we creations of that book, The Bible, can't endure Lucretius' lush relish and

appreciation of the sensuous life here on earth. Everything in our abstract,

celluloid-charmed, computer-driven, and, above all, money-maddened lifestyle

separates us from that life on earth."

"Christians, humanists, existentialists—whatever we are—we gaze toward higher,

or at least more interesting things."

"[The] constant of uncertainty—'Planck's constant'—is a very important number in

physics and makes its appearance in many experiments and theories. It has been

grandly called 'the quantum of the cosmos;' but its full title should be 'the

quantum of whimsicality of the cosmos.' Thus, in its ultimate detail the cosmos

is unpredictable, and this is so because we affect the cosmos by looking at it,

that is, because the observer and what he observes cannot be separated.

The metaphor, the myth, of separation between the subjective observer and

objective reality has broken down. There is no observer, no observed. There is

only experience.""'When am I ever selfless?' Why, sir, several times a day,

on the average. For each of us, experience becomes selfless regularly and often.

Every time we either like or dislike something intensely, that thing fills our

consciousness, and our awareness of self vanishes. When we listen to a piece of

music and become intensely involved with it, then the music, as the poet says,

is heard so completely that it is not heard at all, but we are the music while

the music lasts."

"Thus, in any intense experience

the self vanishes. It only enters later as a social and linguistic

convenience when there is talk about the experience. It arises, not from

experience as a whole, but from language—our human language of the last few

dozen millennia—in particular."

"So I relax—or try to, trying to forget the useless conceptions I have been

taught—and let myself change minute by minute. Glitter of sunlight and great

shadows pass over the landscape. If I exist at all, I am like music, forever

modulating into new keys."

"Sometimes when I can leave off for a while the actions and thoughts which keep

defining a self for me unawares, I sit still and feel that nothing—feel it as

something positive, something mysteriously, actually there. The zero, the real

person, the central being. That which will slip and slide outside of any

definition, any set of actions, any work of art even. This central person, this

true self, will never be found. We deal with it every day."

"Nowadays we make quick work of our courtships; it's our divorces that we spend

a lot of time on."

"Logic, like Rilke's angel, is beautiful but dangerous."

" . . . what I love best is humor and horror happening at once . . ."

"I think I was lucky in this one [Sonnet 11 from Word from the Hills,

which appears below]. But I had put myself in the way of good luck by throwing

in my lot with the sonnet form in the first place. Over and above [its] specific

effects, the poem acquires a power and authority simply by being carried out

with apparent ease in a recognized and recognizably difficult verse form."

[Lucky and very good, we'd say.]

from Word from the Hills

a sonnet sequence in four movements

11

You were so solid, father, cold and raw

as these north winters, where your angry will

first hardened, as the earth when the long chill

deepens—as is this country's cruel law—

yet under trackless snow, without a flaw

covering meadow, road, and stubbled hill,

the springs and muffled streams were running still,

dark until spring came, and the awful thaw.

In your decay a gentleness appears

I hadn't guessed—when, gray as rotting snow,

propped in your chair, your face will run with tears,

trying to speak, and your hand, stiff and slow,

will touch my child—who, sensing the cold years

in your eyes, cries until you let her go.

Published in Sparrow,

Fall 1994

Richard Moore's life, work and death are

now honored below by his friends among the poets and his fans among readers of

poetry and literary prose. We will miss his razor-sharp wit, honed on the lathe

of life, and his determination to always tell the truth as he perceived it.

Richard never pulled any punches, and some of his wildest salvos were aimed at

himself. But if the purpose of an artist's life is to create enduring art,

in the end his life should—no, must—be judged by the monuments of his own creation.

Now here, without further ado, is what "people in the know" thought of

Richard Moore and his art . . .

Richard Wilbur,

perhaps America's foremost Formalist since Robert Frost, had this to say

about Moore's seventh collection of poems, Bottom Is Back, Orchises

Press, 1994: "The best and most serious poetry is full of gaiety, and it is only

dreary poets and their too-earnest readers who consider light verse demeaning.

X. J. Kennedy is right to remind us, in his prefatory poem [below], that funny and

satiric poets will dine at journey's end with the likes of Byron, Bierce, and

Landor. In any case, if the reader will look at such a delightful and flawless

poem as Richard Moore's "In Praise of Old Wives," the question of light verse's

legitimacy will become academic.

Richard Moore was a unique as a man and as a poet. His sudden passing leaves

a void in American letters that will never be refilled. I count myself

fortunate to have been his friend for nearly 40 years.—X. J. Kennedy

Sharing the Onus

by X. J. Kennedy

For sure, Dick Moore, what fate is worse,

And are we not delirious

To wear the curse folks cast on verse

Acerbic and unserious?

Some, for whom cuddling with the times

Is chief modus vivendi,

Indict our rhymes for all known crimes

Save trying to be trendy,

And placing their respect in worms

Indignantly insist

That all Creation’s vilest form’s

An epigrammatist.

Straight-faced as stuffed owls stuck on rods,

They load up and besiege us

Poor rhyming clods with fusillades

Of open verse egregious—

But let’s not one iota veer

From meter, craft, and candor

And yet aspire to hoist brown beer

With Byron, Bierce, and Landor.

Richard Moore was one of our major poets. I first came

across his work when asked to review A

Question of Survival (l971) and A Word

from the Hills (l972) for Library

Journal. I still find these books to be very important to an understanding

of Richard's work along with Empires

(l98l) and his brilliant critical book The

Rule That Liberates. Along with X. J. Kennedy and Roger Hecht, he was one of

the poets from his generation who helped form the basis of the Expansive

Poetry/New Formalism movement. He never relinquished his integrity and

convictions to the petty politics of poetry.—Frederick Feirstein

"I like this book [A Question of Survival] wondrously well, admiring

the skill and bite of it immensely. At their best, Moore's poems are funny and

serious at once—by no means light verse."—Howard Nemerov, Poet Laureate of the

United States

May Swenson concurred with Nemerov's assessment of A Question of Survival,

saying: "Here, with this first book, is a poet full-grown. These are healthy

poems. There should be no question of survival—for either the man or the book."

We recently stumbled on two new poems (or at least new to us) by Richard Moore,

so I'd like to share them. The title of the first poem, with its double-l,

reminds me that Richard sometimes used "more British" spellings of words. When I

inquired about such things, he usually agreed to use the "more American"

spelling.—Mike Burch

The Wherewithall

by

Richard Moore

I wake, thinking my body out there, motionless,

or is it in here? If I move it,

bring it to life, know it, familiar there, right there,

complexity of leg, arm, torso,

when all that body comes unfolding out of me

soon now, it will be like a bird’s leg,

extending downward, helping me to stand upright

on ground. In sleep, I’m the bird flying

with brave thoughts flapping, body folded into me

so that it vanishes, not needed.

I’ll want it, landing on the other side of sleep,

the other side, maybe, of dying.

The Accident

by

Richard Moore

Ah, reader, do not laugh

at mishap’s epitaph.

The muse of poetry

was like his S.U.V.

She filled him so with wonder,

he got in her and gunned her.

I'm glad you're doing this for Richard, Mike: his work

deserves it. His death is a loss to poetry, and to us all. Best wishes.—Rhina

Espaillat

"I corresponded sporadically with Richard Moore over the

last fifteen years, sometimes exchanging poems, and occasionally longer letters

on aesthetic questions. He was a

thoughtful and considerate correspondent who never failed to have something

important and interesting to say on the subject at hand—whether it was poetry,

politics, religion, history, philosophical ideas, or just whatever momentary

notion he had latched upon as fascinating and perhaps worthy of treatment in

verse. Like a true Renaissance man,

he could discuss any subject intelligently, from Greek drama to aerodynamic

design. That’s what was so

delightful and poetically fruitful about Moore’s habits of thought: he was willing to explore the

possibilities of anything and everything in a spirit of true Aristotelian

wonder. And by practicing a rigorous

kind of self-isolating asceticism, he devoted all of his energy to his art in a

way that is uncommon in the contemporary poetry world of networking,

grant-scrounging, and conference-hopping.

I will miss his carefully penned letters in small, precise script; his

gentle but firm voice on the telephone; and above all his immense talent, which

was still volcanically active right to the end.

Farewell, friend, and may the earth rest lightly upon you."—Joseph S. Salemi

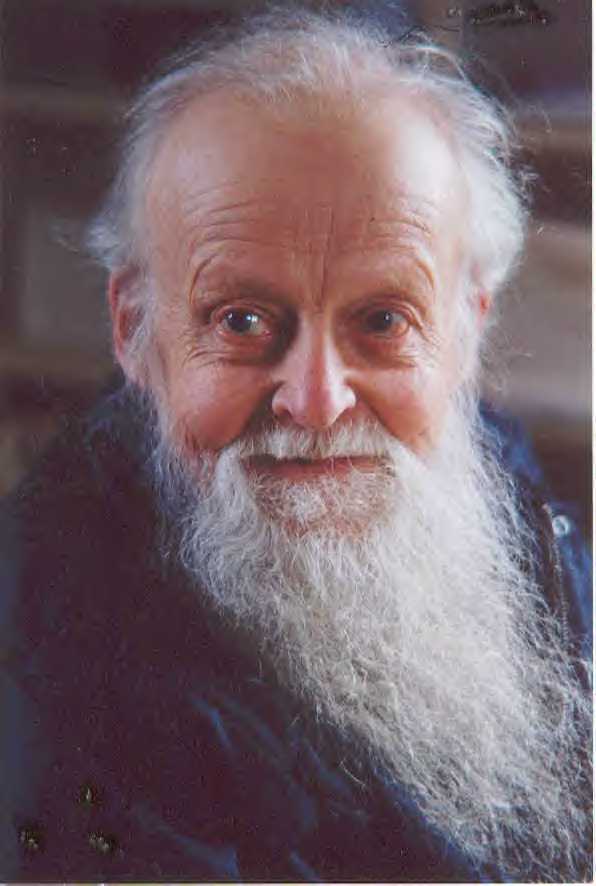

On Seeing a Lock of Richard Moore’s Beard

by Jared Carter

Richard, thou once wert almost indestruct-

Ible and bushy bearded; – now thou‘rt plucked!

All that remains of thee these plaits infold –

Able to tickle still, and never to grow old!

"What a wonderful mind he had!"—Jean Mellichamp Milliken, editor of

The

Lyric, in a letter to THT editor Mike Burch

Richard Moore was a wonderful mentor to me, and purely out of

generosity. He wrote to me ten or twelve years ago in response to a review

I had published somewhere (I don't even remember where or of what), and we

corresponded for a while before we began to exchange poems. It was

intimidating to send my work to someone so far along in his career and whose

erudition was so far beyond my own. He had a knack, though, for building

my confidence even while he challenged me to reach deeper, to be ever-more

demanding of myself. The great pleasure, though, was being introduced to

his large and diverse writings. Essays, novels, poetry that ranges from

couplets to epics—over the years I accumulated a library of his work in which

I find new pleasures with each visit.—Richard Wakefield

I remember the happy genesis of your epic as you gleefully helmed

"Iteration" across a sparkling Buzzard's Bay. Sail on with fair breezes,

Richard, and give our regards to Stuart Little when you speak him in

Hadley's Harbor.—Bill Bowers

Our sailing with Richard on the Bay was memorable, and

no doubt gave stuff to fuel his imagination, if not the genesis of the epic

tale [The Mouse Whole]. His signed copy made for a delightful subsequent summer's reading a few

years later, and is a treasured part of Iteration's library. My wife

Linda's uncle Dick was a bright light in our lives, and we will miss his sparkle

at family holidays. You certainly may share that happy memory of our

sailing poet at large!—Bill Bowers

Eternal Testament

by Mike Burch

Richard, my friend,

they say it’s the end,

yet your words endure—

like hammered gold, pure.

And while there’s no use denying

the horror of dying

or the perils of living,

still there’s room for thanksgiving:

you overcame every pain.

Let your words remain.

Amen

"He made me laugh when he told me that he had some medical problems but none

that was serious enough to suit him."—Ian Thornley,

who visited Richard Moore after he made the decision to stop seeing his doctors

and die on his own terms

"Dick Moore and I were classmates at Loomis School in Windsor Ct where we

were boarders for four years most of which were during World War II. We spent

many hours talking about the ways of the world. He questioned the world: I was

more of a conformist trying to please. We played chess and both wrote poetry.

Then we both were accepted at Yale and were classmates for another four years. At Yale our paths seldom crossed and I cannot explain why. I guess we simply

found different friends.

Over the years we have kept in touch via the Loomis Chaffee School alumni magazine,

occasionally writing to each other to comment on what one had learned about the

other from the blurbs in the class notes. Dick encouraged me to work on my

poetry and I enjoyed reading his. I never made a commitment to poetry but he

most certainly did. In recent years we emailed about a visit but we never got

together. We have lost a very fine, penetrating mind which could see through

sham and pretense, but also had a whimsical side. He was one of a kind. I am so

sorry to hear of his passing."—Dave Burnham

A Critical Appreciation of the Work of Richard Moore

by

Art Mortensen

I have talked too much already. Reader, what you have found in

these poems, if anything, is as surely in them as what I find. I am but a reader

of them now myself. I have lived since. The person who wrote them is a stranger.

Richard Moore

Postscript to Empires

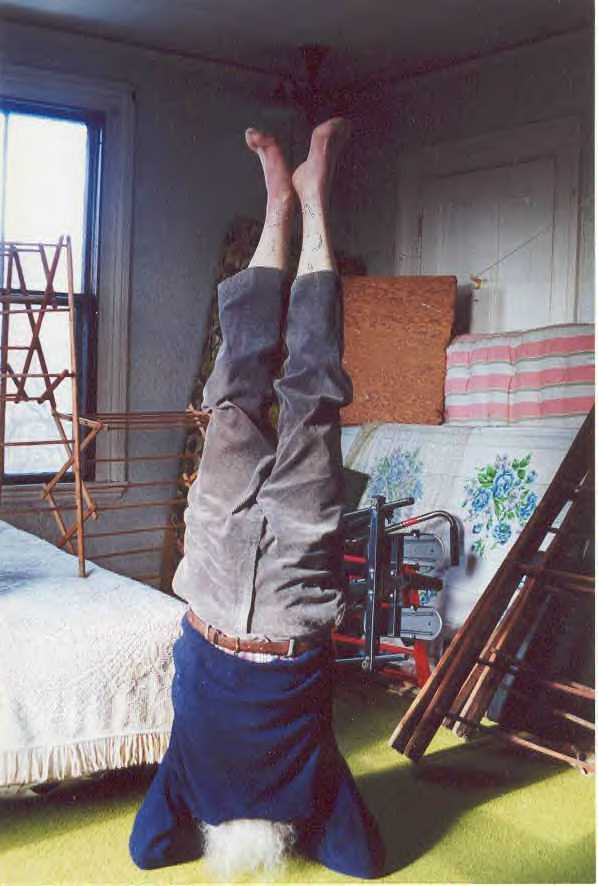

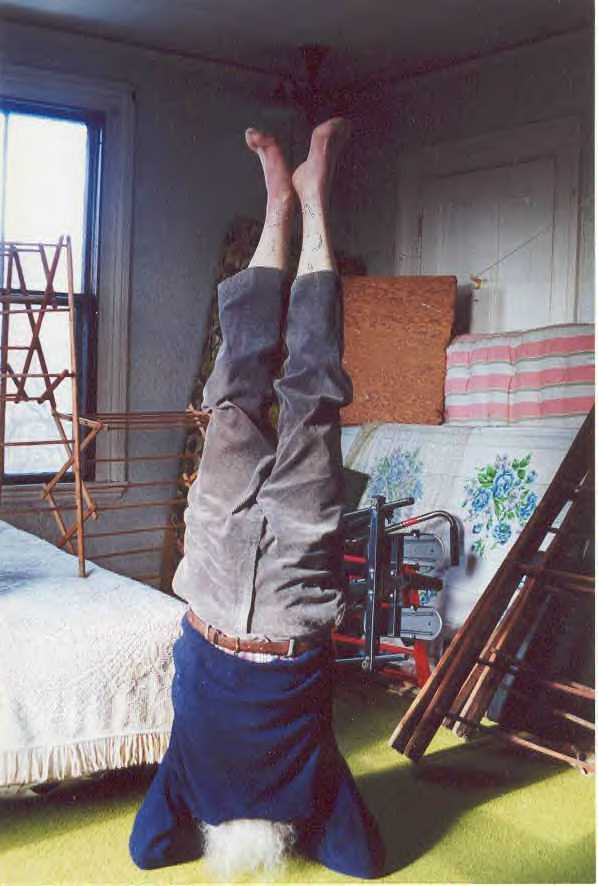

Had you taken his appearance to heart, the enormous white

beard, the wiry, thin body, the poor teeth, the starting eyes, and the frequent

complaints about age, you might have begun to mourn Richard Moore decades ago.

But, you would have missed the man altogether. Long before this writer met him,

the poet had reconceptualized himself as an old man. (This is from testimony of

a number of his colleagues.) One of his very oldest friends once suggested that

Richard began to play King Lear when he was forty-five, not as a tragic posture,

but as a comic one. And, in conversation long after, Moore told this writer that tragedy was a

perspective impossible in a world whose only abiding faith, and where the only

evidence to support it, was found in the material. And, in the same

conversation, the poet, ever a fine critic as well, suggested that an honest

reading of King Lear would show the author presenting much the same point of

view in 1608. Richard would offer these sage, impromptu essays for those who

didn’t get it, usually with a twinkle in his eye, and a reinforcing quotation at

length from the tens of thousands of lines of other people’s poetry he held in

memory, or from his own. Reading Moore, you can’t miss that of course. Even in

his most serious and lengthy pieces, whether The Mouse Whole, Empires, the

sonnet sequences or the elegies, the Dedekind cut between the darkest of

comedies and tragedy is never crossed. Richard didn’t believe in that.

And yet Moore didn’t compensate for that sensibility by surrounding himself with luxury, what

Fitzgerald described as the best revenge. The old Victorian he lived in, while

fundamentally sound in structure and its various systems, as you’d expect a New

Englander’s house to be kept, was a nightmare for anyone who didn’t take delight

from its eclectic collections of broken down equipment, oddball sculptures,

scattered books, an unkempt yard, unmatched and, one suspected, found furniture,

and floors some of which looked as though they hadn’t been scrubbed in half a

century. For Richard, such compensations, common in any neighbor's house, were

for him just more, unnecessary illusions. But, who went to that house to reflect

on Richard’s material status?

What was real for him lay in the abstractions exacted from his

long love and study of geometry, the complexities of prosody, and the ineffable

surprises of rhyme—in both his own and many others’ work. And there was a

complementary order in that house. It wasn’t hard to find. He would always show

it to a guest, whether in the many, neatly stacked boxes in his tiny study, each

filled with carefully numbered and dated poems and essays, or in the solitary

room he set aside for preparing submissions, as well-supplied as a company

office’s mailroom. To publish a thousand poems, and eleven books, especially

nowadays, requires order not only in producing the work, but also in cataloging

it and getting it out the door.

And there was that wonderfully ordered mind. Moore often angered people

with his tart remarks, but he probably couldn’t help himself. He could smoke out

fakery a mile away. If you flubbed your logic, or argued off the point, or

misquoted, or in general transmitted stupid ideas to Richard, his eyes would

glitter, and he’d make it clear that you should try another tack, or investigate

another subject.

All of that is gone, or soon will be, as he would not hesitate

to tell anyone who suggested otherwise. But we still have the finest of his

orders: the poems and essays. The usual course after a poet’s death is for the

work to vanish from critical and public view for a quarter of a century or more,

as if there were something slightly unseemly about enjoying a poem by someone

who had just died. That’s a ritual best ignored in the case of Richard Moore.

Now is the best time to enjoy those poems and essays, whether again, or for the

first time.—Arthur Mortensen

Many Mansions

by C.B. Anderson

I’d grown accustomed to being offered toothsome creations in the epigrammatic

style, with their extreme compression, gnomic wit, and improbable rhymes.

But little did I know that I had only been sampling the hors d’oeuvres.

And it was a skewed sample, since I was late to ante up in the Great Game.

I’m not the least bit ashamed to admit that Richard Moore called my bluff

with the full house he had drawn, and I’ll never complain about being served a

lavish dinner that would satiate even the most intemperate glutton.

The poems that slaked my appetite and left me owing him the ranch appear

in The Raintown Review (Volume 6 Issue 1, February 2007). Inside are a canzone and two other poems of Moore's which, to the best of my knowledge, are nonce forms,

all with stanzas that loom on the page like Gothic mansions. These structures are spacious, inhabited by arresting images, and imbued

with a vatic seriousness. For

example, from “The Swarm”:

Blowflies explode from nowhere as I walk.

The hot pavement below me glares like chalk.

Brown on the bleached cement,

I spot the bit of filth from which they flew,

crusted and dry, and poke it with my shoe,

and it shines wetly. Intent

buzzings return, bent

in spirals on the food,

or quick scribbles of shrinking amplitude,

to the fruit, now impossible to find

under its fly-thick, greenly nervous rind.

I think you get the idea: Density, served raw in vasty parlors.

Even gamblers need to eat occasionally, and every sailor who plies the noosphere

should look forward to the prospect of an equable mooring.

Though he didn’t know me well—or at all, for that matter—Richard

Moore nonetheless invited me to roam freely through the long hallways of his

richly appointed habitation.

Thanking Seashells

by T. Merrill

for WS

He lives, beyond his life, in many

projections,

in many imagined things,

though only as speaker,

as one to whom it is possible only

to listen . . . and listen.

He never listens himself anymore,

his hearing having grown impaired;

never hears ceilings or floors

channeling rare selections

through a medium uniquely attuned

to whatever-the-matter's tongue;

no, he only broadcasts now,

a distant turbulence funneled

like wind through a conch—like ocean's

ferment echoed afar,

like some deeply inconsolable sound

from fathomable depths offshore.

[Tom Merrill was working on this poem at the time I learned of Richard Moore's

death, and had emailed me a copy, and while the poem is not about Richard it

reminded me of Richard, so I asked Tom if I could use the poem for this memorial

page and he graciously agreed.—Mike Burch]

"I just read Moore's essay 'Pain and Death' and found it

touching. I hope it somehow worked out for him the way he was hoping, no

hospitals, surgeons, knives or opiates, and most importantly no misery. I agree

with Caesar—"sudden" is best. ... I'm saddened by

Moore's death; he was always part of my poetry landscape,

one of the old guard I suppose one could say, like Snodgrass, whom I also miss

without ever having known him. I wish they were both still part of the active

conversation. Both good men, both, alas, gone forever."—Tom Merrill

"I'm not sure how it is that you have found me through my current e-mail address,

but I am glad of it. Strangely, I have, for some time, considered getting in

touch with Richard Moore (through the e-mail address provided in The Deronda

Review) regarding several of his recent longer poems that impressed me greatly.

They reminded me of some of W.D. Snodgrass's best work. Unfortunately,

communicating with living colleagues is not the work I am best at, which seems

to be a recurrent theme in the story of my life. Anyway, for what it's

worth to the living or the dead, I would like to post the tribute poem that

appears below. Also, since I happen to live near

Boston, I would like to know the details of the December

3 memorial service that will take place there."—

C.B. Anderson, in a letter to THT editor Mike Burch

Forever Moore

by

C.B. Anderson

Too wry by half,

he bade me drink

his verbal tea

straight from the pitcher.

He made me laugh

and made me think,

and there I'd be,

a maxim richer.

From staples to

the kitchen sink...,

his words attest

a hardware store!

Obliged to chew,

I sense a wink

when I digest

a trope from

Moore.

Letter from a Poet

by Mary Rae

For Richard Moore

The letter came adorned with just one stamp

with cancellation showing where the thought

of you first lit his mind and made him plot

his course: he drew some paper near a lamp,

then grasped the pen that, in his steady hand,

could not be anything but orderly.

He could have sent an email off for free,

but felt, perhaps, what few would understand,

that there was life in paper and a pen;

not DNA, but bounties of intent.

And when he wrote of Catullus or Swift,

his ink would pool in seas beyond your ken,

and islands where he cut his mind adrift

would float across an age—the letter sent.

"It is a difficult thing for this community of poets and friends to lose

someone like Richard Moore. His writing was clean-edged and direct, yet could

disarm you with humor and moments of deep tenderness. This was a man we all

wanted to know better. I don’t think there is anyone here who hadn’t hoped to

meet Richard, or to see more of him; who hadn’t wished to begin a

correspondence, or to receive just one more letter, full of wit and sobering

kindness. I never met Richard in person, although we had intended to get

together in Virginia where my family lived; but our plans never coincided. Going

through the handful of letters that were part of our correspondence when I was

editor of Romantics Quarterly, I came across a letter from 2004 in which Richard

wrote, with his characteristic clarity: 'Life is short, and seems to keep

getting shorter.' But I never imagined it wouldn’t be long enough for me to meet

him."—Mary Rae, poet and former editor of

Romantics Quarterly

Mary Rae also graciously provided us with the poem below,

originally published in The Epigrammatist, which Richard Moore had

mailed to her:

Catullus, V

(in the meter of the original)

by Richard Moore

Live, live, Lesbia, O, and take our loving.

Talk, tales, cackles of our severer fogies,

all their "values" let's value at a penny.

Old suns setting and rising when they're able . . .

round us, once it has set, our brief, our own light,

night comes always together then for sleeping.

Give me kisses. A thousand. Then a hundred.

One more thousand. And then a second hundred.

Cram time full with the thousands we'll be making,

all mixed up, so that we won't know how many—

not some evil-eyed dotard curse us, counting

just how many we've got stashed up in kisses.

Side by Side with Richard Moore

by Edmund Conti

When Light came in the door

I looked for my poems first

Then on to Richard Moore

To see whom he had cursed.

Those who gained from capital gains.*

General Custer’s nagging wife.**

Sometimes Doers gave him pains.***

Ecologists, too, would get the knife.****

I read them, thought, Hey, that’s not right.

Where’s the fun, the joy? Forsooth!

What’s Moore?

It wasn’t always Light

But it always was the truth.

*Light No. 48

** Light 36-37

***Light 31

****Light 49

On the Ascension of Richard Moore

by John Mella

Richard Moore!

I follow your spoor

Across the wasted landscapes—

Where the Muses sung,

And the beetles (dung)

Play their rollicking poisonous sand tapes!

Dear Richard Moore,

This rhyme’s a bore,

But your name’s among the immortals!

With Dante’s chaff

To make you laugh,

You’ll swing open those heavenly portals!

"I've encountered Richard Moore's work only on The HyperTexts, and I like all that I've

seen there. On the strength of Moore’s poetry, and the

strength of five sentences in his essay "On Rhyme," I have just ordered three of

his books. These five sentences state in a nutshell the reason for rhyme, and

the reason 21st century poetry will eventually return to it, unless I miss my

guess. Here they are: '[T]he very difficulty of finding rhymes in English is

an important reason for them. Art thrives on difficulty. The audience (if there

is one) delights when the poet, like the impossible archer, hits the mark. What

effortless grace! Such deeds seem beyond human skill.'

Perhaps that's because they are the fruit of working deeply in meter and rhyme—and they are."—Leland Jamieson

"I'm sorry to learn that Richard Moore has left the

Earth. I have no doubt that he will create his own mischief and wonder,

wherever he goes now."—Ursula T.

Gibson

When someone who has touched your life

leaves this Earth to find out more than we know,

the sadness grips us briefly, but then

we realize the opportunity to know EVERYthing

will be welcomed and utilized quite well.

Ursula T. Gibson, in memory of Richard Moore

Farewell, Far Voyager

by Mike Burch

Richard, I wonder:

in the great blue yonder

does the boy whose pockets

squirmed

with worms

hear the thunder

and eye the sockets

where bizarre lightning forms . . .

and understand Storms?

Richard, be well

beyond heaven and hell,

if there’s an iota of grace

and touch God’s face.

"When I think of my friend Richard Moore, I will always remember the boy with

worms in his pockets (perhaps because he identified with them, perhaps because

he believed even worms deserve defenders) who overcame legions of obstacles to

become one of America's foremost writers and scholars. Perhaps a greater

wonder than my poem’s would be for God to wonderingly touch Richard’s face."—Mike Burch

As we begin to wrap up this page, please allow me to offer a few poems of

Richard's in his own remembrance . . .

The Conquest

A curious place you found finally to please our senses

after the Continent had witnessed your defenses,

to lead me up that hill where daws and eagles roost

above that town where holy pageants are produced,

as if you'd show me all the kingdoms of the world.

The sun licked over swells of skyline; darkness curled

its long exploring shadows through the waiting hills.

Winds blew, and I lay helpless in the evening's chills.

You were untouched....What could I do there, face-to-face

with countries watching me, and sky, and wordless space

as empty as this solitude in which I live?

Your silence said, "If they are you, what can you give

of them? Those shadow kingdoms in you? Watch them pass!

Can all that space find one white body in the grass?"

Then over a carved table later on that night,

I looked into your face, subdued, saddened, and white,

and was uncomfortable, and became almost cross,

stiff, like a mourner, mourning primly his great loss.

Poem about Vietnam that Didn't Suit Anybody at the Time

The very skies grow soiled and clammy.

Autumn has come to 1967.

Thunderous Yellowbirds climb south to Miami,

the shrill vacuum cleaners of Heaven.

The ducks rise up in careless ranks

and disappear into the Great Beyond;

I stand where shrinking water bares its banks

and skip flat stones across the pond.

Lyndon is in his great white mansion;

peace-loving students storm the Pentagon.

I stay right here, coiled up inside my scansion,

while all these dreadful things go on.

Lyndon, no matter how adept,

no matter how proficient the machine,

the floor of Heaven still remains unswept,

there are some things we cannot clean.

There is a destiny that fails.

Asia has felt the heal of our empire,

clung to the heel, sucked out the shiny nails

(such is the virtue of a mire),

and now the boot is falling off;

I think the white and naked toes grow fungal;

I do not think our minds will ever doff

what they put on in Asia's jungle.

I hear a mother's anxious tears

who supplicates her decorated hero

to throw away that nasty bag of ears

that she found, cleaning out his bureau.

The dandelions that rule my lawn

are difficult to search out and destroy;

their buried roots remain, and when I'm gone

new seedlings secretly deploy.

Good weed killer, dumped on en masse,

Lyndon, I hope will work with greater ease—

distinguishing intruders from true grass—

on dandelions than Vietnamese.

Though rioters shall feel the rod

and half the banks in Texas feed you profit,

though you have Sunday-breakfasted with God

and Billy Graham, His hired prophet,

Lyndon, things haven't gone so well

for you, for me, and for this hectic Nation.

You've worked too hard. Why not go home now, sell

the ranch, the banks, the TV station,

and join me here beside the pond,

pitching these skipping stones? Catastrophe

will come, need not be wrested, begged, nor conned.

It needs no help from you or me.

Forget the poor and how they house;

forget the protocol, the Paris gowns;

watch how the clever stone skips, skips, then plows

so gracefully before it drowns.

53

Gee-gees were horses, ta-ta

her first word

for her dark faeces, when through hay and heather

toddling, we stopped to see, as dry as leather,

a heap of lumps, a hummock of horse turd;

and, Da? she questioned, who had only heard

meaningless names till then—when like a feather

a thought struck and I put her words together,

not once daring to hope for what occurred:

she stood there, silent, puzzled,

open-eyed,

as if I'd handed her some shiny token,

then, Gee-gee ta-ta...gee-gee ta-ta! cried,

as if a shell surrounding her had broken,

and shouted still, till all the hills replied—

till the dark hills surrounding us had spoken.

Wine

Patience! Her disposition may get

sweeter

after her daily liter.

She grows talkative, gay, loses her cares

and footing on the stairs.

I watch, hoping she'll fall and bust her kisser,

forgetting how I'd miss her.

Yet Another Apology

Why's he so cutting, ironic, unkind,

like those bitter old pagans of Greece?

"A positive mind is a turbulent mind."

My negative mind is at peace.

More or Less

by Michael R. Burch

for Richard Moore

Less is more —

in a dress, I suppose,

and in intimate clothes

like crotchless hose.

But now Moore is less

due to death’s subtraction

and I must confess:

I hate such redaction!

Richard Moore was capable of what Keats called "negative capability."

In closing, although we need never close the book on Richard Moore and his work,

there were a few "mystical moments" (or were they "misty-eyed" moments?) as I

worked on this page into the wee hours of several mornings, and I'd like to

describe what happened for readers who may be interested in such things.

Albert Einstein said God reveals himself through coincidence. From the day

Richard died, on November 8, 2009, to the day I finished the first iteration of

this page, I had a number of what I call "harmonic convergences." I have an aunt

who calls them "God incidences." I'm not sure what we mean anymore when we say

"God"—a sometimes benevolent Man in the sky who turns into the Devil and

sentences human beings to an "eternal hell" whenever priests and pastors want

money and more baptisms seems increasingly unlikely, and not someone I'd like to

encounter myself—but it does seem at times that we are all "connected"

somehow, and that things sometimes seem to happen with some degree of rhyme and reason,

although the ultimate reason remains unfathomable . . . unless, as the mystics of all

religions claim, we are like the individual waves that rise from a great sea of

Unity. I've never had such a revelation myself, but poets like Whitman and Rumi

did, and mystics like Julien of Norwich, who claimed to have heard the voice of God say, "All

shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well." While it's quite a leap

from the harmonic convergences I experienced to Universal Nirvana, still one can

live in hope, so I will mention them for anyone

interested in the "ripples" or "wake" (pardon the pun) my friend Richard Moore

may have left with his passing . . .

Before I learned of Richard's death, I had a very vivid dream. He and I were playing

pool together. I was attempting a very difficult shot, which involved leaping

the cue ball from one table to hit the head of a small nail positioned on another table some

distance away. I took the shot and believed I had succeeded, but when Richard

examined the evidence, he was unconvinced. At the end of my dream, he was

screwing his pool stick together, presumably to execute the shot himself. I have a

"sense" of what this dream may "mean" and if anything happens, I will mention the

results here and in the Current & Back Issues section of THT.

The two longest poems published by THT to date, by a longshot, are Richard

Moore's "The Mouse Whole" and Ian Thornley's "Song of a Sun of Light." Ian had

visited Richard Moore three times, and being a doctor who works with terminal

patients, had been able to discuss the end-of-life process with Richard. As I

updated THT after Richard's death, but before I learned about it, I noticed that

the two poems are exactly the same size: 355KB. That seems like a remarkable

coincidence, but I only noticed it after Richard's death.

I am normally quite coordinated, but as I was walking down a flight of stairs to

my office, some Diet Coke splashed out of a nearly empty can I was carrying, and

sloshed on a pile of books heaped on the steps. When I bent down to examine the

damage, I didn't find any coke, but I did find a copy of Richard's first book of

poetry, A Question of Survival. Was Richard or the Universe somehow

suggesting that I do something with the book? On the back of the book I found a

prophecy by May Swenson: "There

should be no question of survival—for either the man or the book." I found this

comforting, and wondered if Richard might have wanted this

prophetic blurb published on his memorial page.

A poet asked me for the email address of a poet whose initials are R. W. (I

assume this other poet was someone close to Richard Moore). When I glanced down

at my file list, although their last names would have kept them apart, I had

created their files with their first names followed by underscores, so they

appeared side-by-side on my screen.

Although I own a software company and send and receive hundreds of emails weekly

with few problems, I was unable to receive emails for Richard Moore's literary

executor. So we had to "conduct our business" on Facebook, which means we left a

public record of our discussions about Richard, which therefore means that more people may

read about his memorial service, and this online memorial.

After Richard died, but before I learned of his death, Tom Merrill emailed me

his poem "Thanking Seashells" (which now appears on this page) and it reminded

me of Richard's poems about empty houses by thundering seas (and particularly of

his poem "Depths," which appears on his THT poetry page). And Tom's lines about a

hearing impaired poet growing deaf to his own ceilings and doors made me think of Richard with his

deteriorating body, facing death in his ramshackle deteriorating mansion. While Tom was not

consciously thinking of Richard Moore when he wrote his poem, his poem certainly

"converged" with my thoughts about Richard and his mansion close to the sea in

Boston.

Mike Burch

11-19-2009

The HyperTexts