The HyperTexts

Arabic Poetry Translations by Michael R. Burch

These are modern English translations of Arabic poems by the Palestinian poets

Mahmoud Darwish, Walid Khazindar,

Nakba,

Kamal Nasser,

Fadwa

Tuqan and

Tawfik Zayyad.

FADWA TUQAN

Fadwa

Tuqan (1917-2003), the Grande Dame of Palestinian letters, is also known as

"the Poet of Palestine." She is generally considered to be one of the very best

contemporary Arab poets. The sister of the poet Ibrahim Tuqan, she was born in

Nablus in 1917. She began writing in traditional forms, but became one of the

leaders of the use of the free verse in Arabic poetry. Her work often deals with

feminine explorations of love and social protest, particularly of Israel's

occupation of Palestinian territories.

Enough for Me

by

Fadwa

Tuqan, a Palestinian poet

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

Enough for me to lie in the earth,

to be buried in her,

to sink meltingly into her fecund soil, to vanish …

only to spring forth like a flower

brightening the play of my countrymen's children.

Enough for me to remain

in my native soil's embrace,

to be as close as a handful of dirt,

a sprig of grass,

a wildflower.

Existence

by Fadwa Tuqan

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

In my solitary life, I was a lost question;

in the encompassing darkness,

my answer lay concealed.

You were a bright new star

revealed by fate,

radiating light from the fathomless darkness.

The other stars rotated around you

—once, twice —

until I perceived

your unique radiance.

Then the bleak blackness broke

and in the twin tremors

of our entwined hands

I had found my missing answer.

Oh you! Oh you intimate, yet distant!

Don't you remember the coalescence

Of our spirits in the flames?

Of my universe with yours?

Of the two poets?

Despite our great distance,

Existence unites us.

Nothing Remains

by Fadwa Tuqan

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

Tonight, we’re together,

but tomorrow you'll be hidden from me again,

thanks to life’s cruelty.

The seas will separate us ...

Oh!—Oh!—If I could only see you!

But I'll never know ...

where your steps led you,

which routes you took,

or to what unknown destinations

your feet were compelled.

You will depart and the thief of hearts,

the denier of beauty,

will rob us of all that's dear to us,

will steal our happiness,

leaving our hands empty.

Tomorrow at dawn you'll vanish like a phantom,

dissipating into a delicate mist

dissolving quickly in the summer sun.

Your scent—your scent!—contains the essence of life,

filling my heart

as the earth absorbs the lifegiving rain.

I will miss you like the fragrance of trees

when you leave tomorrow,

and nothing remains.

Just as everything beautiful and all that's dear to us

is lost—lost!—when nothing remains.

Labor Pains

by Fadwa Tuqan

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

Tonight the wind wafts pollen through ruined fields and homes.

The earth shivers with love, with the agony of giving birth,

while the Invader spreads stories of submission and surrender.

O, Arab Aurora!

Tell the Usurper: childbirth’s a force beyond his ken

because a mother’s wracked body reveals a rent that inaugurates life,

a crack through which light dawns in an instant

as the blood’s rose blooms in the wound.

Hamza

by Fadwa Tuqan

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

Hamza was one of my hometown’s ordinary men

who did manual labor for bread.

When I saw him recently,

the land still wore its mourning dress in the solemn windless silence

and I felt defeated.

But Hamza-the-unextraordinary said:

“Sister, our land’s throbbing heart never ceases to pound,

and it perseveres, enduring the unendurable, keeping the secrets of mounds and

wombs.

This land sprouting cactus spikes and palms also births freedom-fighters.

Thus our land, my sister, is our mother!”

Days passed and Hamza was nowhere to be seen,

but I felt the land’s belly heaving in pain.

At sixty-five Hamza’s a heavy burden on her back.

“Burn down his house!”

some commandant screamed,

“and slap his son in a prison cell!”

As our town’s military ruler later explained

this was necessary for law and order,

that is, an act of love, for peace!

Armed soldiers surrounded Hamza’s house;

the coiled serpent completed its circle.

The bang at his door came with an ultimatum:

“Evacuate, damn it!'

So generous with their time, they said:

“You can have an hour, yes!”

Hamza threw open a window.

Face-to-face with the blazing sun, he yelled defiantly:

“Here in this house I and my children will live and die, for Palestine!”

Hamza's voice echoed over the hemorrhaging silence.

An hour later, with impeccable timing, Hanza’s house came crashing down

as its rooms were blown sky-high and its bricks and mortar burst,

till everything settled, burying a lifetime’s memories of labor, tears, and

happier times.

Yesterday I saw Hamza

walking down one of our town’s streets ...

Hamza-the-unextraordinary man who remained as he always was:

unshakable in his determination.

My translation follows one by Azfar Hussain and borrows a word here, a phrase

there.

More translations can be read here:

Fadwa

Tuqan

MAHMOUD DARWISH

Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008), the Poet Laureate of the Palestinians, was the preeminent Arab poet of his day.

Darwish was

a Palestinian Arab born in the

Galilean village of Barweh, which was razed to the ground

by Israelis during the Nakba ("Catastrophe") of 1948, along

with hundreds of other Palestinian villages. Like hundreds

of thousands of Palestinians, Darwish became an exile, along with his

family, because his ancestral village had been destroyed. The title of his

first book, Wingless Sparrows, speaks volumes. It was published when he

was nineteen. And yet Darwish rejected anti-Semitism, saying:

The accusation is that I hate Jews. It's not comfortable that they show me

as a devil and an enemy of Israel. I am not a lover of Israel, of course. I have

no reason to be. But I don't hate Jews.

As a young man, Darwish faced house

arrest and imprisonment because of his political activism. He left Palestine in 1971 to study

briefly at the University of Moscow, after which he worked for a newspaper in Cairo,

then in

Beirut as an editor of Palestinian Issues. When he joined the PLO in

1973, he was banned from reentering Palestine. Still, he recognized the humanity

of the Jews; some were his oppressors, others his lovers:

I will continue to humanise even the enemy ... The first teacher who

taught me Hebrew was a Jew. The first love affair in my life was with a Jewish

girl. The first judge who sent me to prison was a Jewish woman. So from the

beginning, I didn't see Jews as devils or angels, but as human beings.

Palestine

by Mahmoud Darwish

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

This land gives us

all

that makes life worthwhile:

April's blushing advances;

the aroma of bread baking at dawn;

a woman haranguing men;

the poetry of Aeschylus;

love's trembling beginnings,

a kiss on a moss-covered boulder;

mothers who dance to the flute's sighs;

and the invaders' fear of memories.

This land gives us

all that makes life worthwhile:

September's rustling end;

a woman leaving forty behind, still full of grace,

still blossoming;

sunlight illuminating prison cells;

clouds taking on the shapes of unusual creatures;

the people's applause for those who smile at their erasure,

mocking their assassins;

and the tyrant's fear of songs.

This land gives us

all that makes life worthwhile:

Lady Earth, mother of all beginnings and endings!

In the past she was called Palestine

and tomorrow she will still be called Palestine.

My Lady, because you are my Lady, I deserve life!

Identity Card

by Mahmoud Darwish

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Record!

I am an Arab!

And my identity card is number fifty thousand.

I have eight children;

the ninth arrives this autumn.

Will you be furious?

Record!

I am an Arab!

Employed at the quarry,

I have eight children.

I provide them with bread,

clothes and books

from the bare rocks.

I do not supplicate charity at your gates,

nor do I demean myself at your chambers' doors.

Will you be furious?

Record!

I am an Arab!

I have a name without a title.

I am

patient in a country

where people are easily enraged.

My roots

were established long before the onset of time,

before the unfolding of the flora and fauna,

before the pines and the olive trees,

before the first grass grew.

My father descended from plowmen,

not from the privileged classes.

My grandfather was a lowly farmer

neither well-bred, nor well-born!

Still, they taught me the pride of the sun

before teaching me how to read;

now my house is a watchman's hut

made of branches and cane.

Are you satisfied with my status?

I have a name, but no title!

Record!

I am an Arab!

You have stolen my ancestors' orchards

and the land I cultivated

along with my children.

You left us nothing

but these bare rocks.

Now will the State claim them also

as it has been declared?

Therefore!

Record on the first page:

I do not hate people

nor do I encroach,

but if I become hungry

I will feast on the usurper's flesh!

Beware!

Beware my hunger

and my anger!

Darwish was married twice, but had no children. In the poem above, he is

apparently speaking for his people, not for himself personally.

Passport

by Mahmoud Darwish

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

They left me unrecognizable in the shadows

that bled all colors from this passport.

To them, my wounds were novelties—

curious photos for tourists to collect.

They failed to recognize me. No, don't leave

the palm of my hand bereft of sun

when all the trees recognize me

and every song of the rain honors me.

Don't set a wan moon over me!

All the birds that flocked to my welcoming wave

as far as the distant airport gates,

all the wheatfields,

all the prisons,

all the albescent tombstones,

all the barbwired boundaries,

all the fluttering handkerchiefs,

all the eyes—

they all accompanied me.

But they were stricken from my passport

shredding my identity!

How was I stripped of my name and identity

on soil I tended with my own hands?

Today, Job's lamentations

re-filled the heavens:

Don't make an example of me, not again!

Prophets! Gentlemen!—

Don't require the trees to name themselves!

Don't ask the valleys who mothered them!

My forehead glistens with lancing light.

From my hand the riverwater springs.

My identity can be found in my people's hearts,

so invalidate this passport!

Excerpt from “Speech of the Red Indian”

by Mahmoud Darwish

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Let's give the earth sufficient time to recite

the whole truth ...

The whole truth about us.

The whole truth about you.

In tombs you build

the dead lie sleeping.

Over bridges you erect

file

the newly slain.

There are spirits who light up the night like fireflies.

There are spirits who come at dawn to sip tea with you,

as peaceful as the day your

guns mowed them down.

O, you who are guests in our land,

please

leave a few chairs empty

for your hosts to sit and ponder

the conditions for peace

in your treaty with the dead.

My Mother

by Mahmoud Darwish

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

How I long for my mother’s fresh-baked bread,

for a steaming cup of her

coffee,

but mostly ...

for the merest brush of her breath.

Childhood memories well within me...

Day after day,

I must be worthy of my life

and her memory.

And so I must cherish life

because otherwise

my mother's tears would

disown me.

Will the hour of my death

be worthy of her tears?

And if I return one day,

take me for your eyelashes’ shawl,

cover my

bones with the grass blessed by your immaculate footsteps,

entwine us

together with a lock of your hair,

fasten us together with a thread from

the hem of your dress.

Make us secure, never again to be parted.

And if I become immortal,

become a God,

it is only to touch your

heart’s innermost depths.

If I return

use me as kindling to feed your fire,

as the clothesline

strung across your patio,

for without your blessing

I am too weak to

stand.

I grow old ...

Return my childhood star guides

so that I, along with the vagabond

swallows,

can chart the path

back to your welcoming nest.

Excerpts from "The Dice Player"

by Mahmoud Darwish

loose translation/interpretation by

Michael R. Burch

Who am I to say

the things I say to you?

I am not a stone

burnished to illumination by water ...

Nor am I a reed

riddled by the wind

into a flute ...

No, I'm a dice player:

I win sometimes

and I lose sometimes,

just like you ...

or perhaps a bit less.

I was born beside the water well with the three lonely trees like nuns:

born without any hoopla or a midwife.

I was given my unplanned name by chance,

assigned to my family by chance,

and by chance inherited their features, attributes, habits and illnesses.

First, arterial plaque and hypertension;

second, shyness when addressing my elders;

third, the hope of curing the flu with cups of hot chamomile;

fourth, laziness in describing gazelles and larks;

fifth, lethargy dark winter nights;

sixth, the lack of a singing voice.

I had no hand in my own being;

it was mere coincidence that I popped out male;

mere coincidence that I saw the pale lemon-like moon illuminating sleepless

girls

and did not unleash the mole hidden in my private parts.

I might not have existed

had my father not married my mother

by chance.

Or I might have been like my sister

who screamed then died,

only alive an hour

and never knowing who gave her birth.

Or like the doves’ eggs

smashed before her chicks hatched.

Was it mere coincidence

that I was the one left alive in a traffic accident

because I didn’t board the bus ...

because I’d forgotten about life and its routines

while

reading the night before

a love story in which I became first the author,

then the lover, then the beloved and love’s martyr ...

then overslept and avoided the accident!

I also played no role in surviving the sea,

because I was a reckless boy,

allured by the magnetic water

calling: Come to me!

No, I only survived the sea

because a human gull rescued me

when he saw the waves pulling me under and paralyzing my hands!

Who am I to say

the things I say to you

outside the church door?

I'm nothing but a dice throw,

a toss between predator and prey.

In my moonlit awareness

I witnessed the massacre

and survived by sheer chance:

I was too small for the enemy to target,

barely bigger than the bee

flitting among the fence’s flowers.

Then I feared for my father and family;

I feared for our time as fragile as glass;

I feared for my pet cat and rabbit;

I feared for a magical moon looming high over the mosque’s minarets;

I feared for our vines’ grapes

dangling like a dog’s udders ...

Then fear walked beside me and I walked with it,

barefoot, forgetting my fragile dreams of what I had wanted for tomorrow

because there was no time for tomorrow.

I was lucky the wolves

departed by chance,

or else escaped from the army.

I also played no role in my own life,

except when Life taught me her recitations.

Are there any more?, I wondered,

then lit my lamps and tried to amend them ...

I might not have been a swallow

had the wind ordained it otherwise ...

The wind is the traveler's fate: his fortune or misfortune.

I flew north, east, west ...

but the south was too harsh, too rebellious for me

because the south is my country.

I became a swallow’s metaphor,

hovering over my life’s debris

from spring to autumn,

baptizing my feathers in the cloud-like lake

then offering my salaams to the undying Nazarene:

undying because God’s spirit lives within him

and God is the prophet’s luck ...

While it is my good fortune to be the Godhead’s neighbor ...

Just as it is my bad fortune the cross

remains our future’s eternal ladder!

Who am I to say

the things I say to you?

Who am I?

I might have not been inspired

because inspiration is the lonely soul’s compensation

and the poem is his dice throw

on an unlit board

that may or may not glow ...

Words fall ...

as feathers fall to earth:

I did not plan this poem.

I only obeyed its rhythm’s demands.

Who am I to say

the things I say to you?

It might not have been me.

I might not have been here to write it.

My plane might have crashed one morning

while I slept till noon

then arrived at the airport too late

to visit Damascus and Cairo,

the Louvre, and other enchanting cities.

Had I been a slow walker, a rifle might have severed my shadow from its

cedar.

Had I been a fast walker, I might have disintegrated and vanished like a

fleeting whim.

Had I dreamt too much, I might have lost my memories of reality.

I am fortunate to sleep alone

listening to my body's complaints

with my talent for detecting pain,

so that I call the physician ten minutes before death:

dodging death by a mere ten minutes,

continuing life by chance,

disappointing the Void.

But who am I to disappoint the Void?

Who am I?

Who?

More translations can be read here:

Mahmoud

Darwish

Walid Khazindar, a Palestinian poet, was born in Gaza City in 1950. He studied

in Beirut, then lived in Tunis before moving with his family to Cairo. Khazindar

is considered to be one of the very best Palestinian poets; his poetry has been

said to be "characterized by metaphoric originality and a novel thematic

approach unprecedented in Arabic poetry." He was awarded the first Palestine

Prize for Poetry in 1997. In 1998-1999, he was Arab Writer in Residence at the

NESP, Oxford University. To date, Khazindar has published three poetry

collections and his work has appeared in Anthology of Modern Palestinian

Literature. His poems have also been translated in Agenda (1997)

and Modern Poetry in Translation (1998). Some of his poems were

included in Tom Paulin's The Road to Inver (2004). Khazindar also

co-edited The Traces of Song: Selections from Ancient Arabic Poetry

with Munir Sharani.

This Distant Light

by Walid Khazindar

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Bitterly cold,

winter clings to the naked trees.

If only you would free

the bright sparrows

from your fingertips

and unleash a smile—that shy, tentative smile—

from the imprisoned anguish I see.

Sing! Can we not sing

as if we were warm, hand-in-hand,

sheltered by shade from a sweltering sun?

Can you not always remain like this:

stoking the fire, more beautiful than expected, in reverie?

Darkness increases and we must remain vigilant

now that this distant light is our sole consolation …

this imperiled flame, which from the beginning

has constantly flickered,

in danger of going out.

Come to me, closer and closer.

I don't want to be able to tell my hand from yours.

And let's stay awake, lest the snow smother us.

Here We Shall Remain

by Tawfiq Zayyad

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Like twenty impossibilities

in Lydda, Ramla and Galilee …

here we shall remain.

Like brick walls braced against your chests;

lodged in your throats

like shards of glass

or prickly cactus thorns;

clouding your eyes

like sandstorms.

Here we shall remain,

like brick walls obstructing your chests,

washing dishes in your boisterous bars,

serving drinks to our overlords,

scouring your kitchens' filthy floors

in order

to snatch morsels for our children

from between your poisonous fangs.

Here we shall remain,

like brick walls deflating your chests

as we face our deprivation clad in rags,

singing our defiant songs,

chanting our rebellious poems,

then swarming out into your unjust streets

to fill dungeons with our dignity.

Like twenty impossibilities

in Lydda, Ramla and Galilee,

here

we shall remain,

guarding the shade of the fig

and olive trees,

fermenting rebellion in our children

like yeast in dough.

Here we wring the rocks to relieve our thirst;

here we stave off starvation with dust;

but here we remain and shall not depart;

here we spill our expensive blood

and do not hoard it.

For here we have both a past and a future;

here we remain, the Unconquerable;

so strike fast, penetrate deep,

O, my roots!

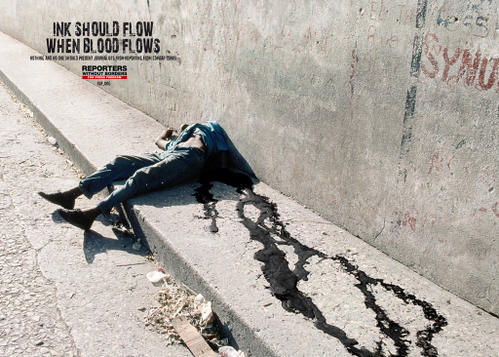

Kamal Nasser

Kamal Nasser was a much-admired Palestinian poet, who due to his renowned

integrity was known as "The Conscience." He was a member of Jordan's

parliament in 1956. He was murdered in 1973 by an Israeli death squad whose

most notorious member was future Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak.

The Story

by Kamal Nasser

translation by Michael R. Burch

I will tell you a story ...

a story that lived in the dreams of my people,

a story that comes from the world of tents.

It is a story inspired by hunger and embellished by dark nights of terror.

It is the story of my country, a handful of refugees.

Every twenty of them have a pound of flour between them

and a few promises of relief ... gifts and parcels.

It is the story of the suffering ones

who stood waiting in line ten years,

in hunger,

in tears and agony,

in hardship and yearning.

It is a story of a people who were misled,

who were thrown into the mazes of the years.

And yet they stood defiant,

disrobed yet united

as they trudged from the light to their tents:

the revolution of return

into the world of darkness.

Kamal Nasser was a Palestinian Christian who was murdered by an Israeli death

squad in 1973.

Nasser was the PLO's most prominent Christian and he enjoyed "great appeal" in

Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq "both as a distinguished poet and likeable

personality." He was the “conscience of the Palestinian revolution,” according

to Nazih Abul-Nidal, who worked with him on the magazine Filastin al-Thawra.

Nasser “had the most democratic outlook of all Palestinian leaders at the time,”

he recalls. Nasser respected opposing views, admired the commitment of young people,

and was a major recruitment asset for the Palestinian revolution. “That is why

he was put high on the hit-list.” The previous year, the Israelis had murdered

another renowned Palestinian writer and activist in Beirut, Ghassan Kanafani, by

booby-trapping his car. Nasser’s successor, Majed Abu Sharar, was also

assassinated by Israelis, in Rome in 1981 while attending a conference in

solidarity with the Palestinian people.

According to Maan Bashour, a member of the PLO information committee and

a representative of the Arab Liberation Front, the Israelis targeted

Nasser specifically because he was seen as "the freedom fighter from Ramallah"

and as "a cultural and media star with his popular and especially Christian

credentials."

The funeral of Nasser and his fallen comrades was attended by the full spectrum

of Lebanese and Palestinian political leaders, including those of the

“isolationist right,” notably the late Pierre Gemayel. Karim Mroue describes it

as having been “the biggest funeral in Lebanon’s history” with around half a

million people mourning in the streets.

Nakba

Nakba is the pseudonym of a Palestinian-American poet who speaks very bluntly

and forthrightly about the plight of

his people, and what he deems the complicity of Jews and American Christians in their destitution. I have intermingled lines from his poems with his

comments about the Nakba ("Catastrophe") of the Palestinians, from which he took

his nom de guerre.

Terror fell upon my children. Wailing,

they ran toward my arms—small, pale with fright.

They seemed eternities from me . . . so distant!

Their day exploded. Now I live in night.

Who infused the missiles with their terrible magic?

"Made in America." I find that tragic . . .

I saw the carnage . . .

saw girls' dreaming heads

blown to red atoms,

and their dreams with them . . .

. . .

saw babies liquefied

in burning beds

as, horrified,

I heard their murderers’ phlegm . . .

"American Christians and Jews have become raging hypocrites," Nakba told

me in an exclusive interview. "They want every possible right for themselves and

constantly preach the glories of democracy, equal rights and justice to the rest

of the world. But when push comes to shove, they steamroll over innocent women and

children if there's something they want: oil, land or water. Why are millions of Palestinians being denied basic human

rights, freedom and dignity? Because Americans want cheap oil and Israeli Jews want free

land and water, at the expense of Arabs. But what has happened? The price of oil

has skyrocketed, and Americans have spent more than a trillion dollars, perhaps

much more, on wars they will never win. Israel has stolen land and water from

the Palestinians for more than sixty years, but look at the toll on the Jews. They

both would have done much better to simply practice what they preach. Perhaps the worst

thing about all the mayhem on both sides is that it is so unnecessary, and

entirely counter-productive. Innocent women and children are dying because Americans

and Jews want "more equal" rights than Arabs. If they would only settle for

truly equal rights, they would save money and avoid what they hypocritically

call 'terrorism,' when by far the greater terrorism is the systematic terrorism

practiced on a daily basis by the governments of Israel and the United States

against millions of innocents."

. . .

I saw my mother stitch

my shroud’s black hem,

for in that moment

I was one of them . . .

. . . I saw our Father’s eyes

grow hard and bleak

to see frail roses severed at the stem . . .

"But the Jews are full of irrational fears, terrified of a Holocaust that

is long over, while Americans are full of grandiose

imaginings that the United States is 'the greatest nation on earth' no matter

how evil its actions ... 'just because.' Of course the Nazis once claimed that

Germany was 'the greatest nation on earth' and had the right to impose its will

on other nations 'just because.' At some point the rest of the world must say,

'We've had enough!' and start to fight back. That's what the people Americans

call 'terrorists' are doing today. I don't agree with their tactics, when they

target civilians, but I understand their anger and resolve. If Americans want to

stop being targets, they should agree to pay to going price for oil (which will

save them trillions of dollars in the long run) and stop supporting the

injustices of Israel against Palestinians. If they did these simple things, they

would save money and lives on both sides. But so far Americans seem content to

rush headlong toward World War III, singing the praises of their glorious

nation, the way Germans rushed headlong toward World War II, singing

"Deutschland Über Alles."

. . .

How could I fail to speak?

I thought of women slain for being born

the "wrong" race, sex, caste, or the "wrong" religion.

I thought of Joan of Arc, her tunic torn,

her breasts exposed, her bloody Inquisition.

"Why should innocent women and children suffer and die, because Americans and

Jews want to have their cake and eat it too? Why should they be allowed to

preach the glories of 'democracy' and 'equal rights' to the rest of the world,

while denying basic human rights and dignity to innocent women and

children?"

His eyes meet mine with blank incomprehension.

"How did you come, my friend, to harm this child?"

"She was not mine, and no report’s been filed . . .

"So what, old chum?" (Strange lines beyond my scansion.)

I felt the flames and then her screams explode.

I thought of Mary and her dolorous road.

"This is why I write . . . in the hope that madmen will come to their senses,

before it's too late. They call their enemies 'evil' without ever asking

themselves 'Is it possible that we did something wrong, to make other people so

incredibly angry with us?' Did the German people ever understand the wrath Americans

felt when they saw the Nazi concentration camps? Well, that's the same wrath we

feel today, when we see Palestinian women and children living in refugee camps,

and inside ghettos with walls twice as high as the Berlin Wall. Why do more and

more people all around the globe look at Americans as if the United States is

the second coming of the Third Reich? Perhaps, because it is."

Sing hymns. Praise God. Erect some higher steeple.

Condemn my kind to poverty, and hell . . .

"Americans and Jews seem to think they get some sort of free pass, simply

because of who they are. They imagine themselves to be 'superior,' to be the

Chosen Few. But the course of recent history says otherwise. Americans and Jews

are alienating the rest of the world. There are billions of people who disagree

that Americans and Jews are entitled to 'special privileges' at the expense of

so many innocents. Yes, there are only around 10 million Palestinians. But they

have 1.5 billion Muslim brothers and sisters who do not take their suffering and

deaths lightly. Nor should they. But Americans and Jews only need to do one

thing, to change the inevitable course of world events. They need to stop

claiming special rights and privileges, and act in accordance with their stated

beliefs. Do they really believe that all men are created equal? Then treat

everyone else as equals. If not, why be hypocrites? At least the Nazis were

honest, that they really did think they were superior to everyone else. Is there

any lower life form than a man who abuses women and children, while praising his

own 'righteousness'? Aren't those ones Jesus reserved all his indignation for:

the self-righteous hypocrites?"

"Shock and awe?" Yes, I feel awe—and shock.

You jackals killed my doves, my lambs, my flock!

Apollyon I - Night of the Apocalypse

by Nakba

His eyes meet mine with blank incomprehension.

How did you come, my friend, to harm this child?

"She was not mine, and no report’s been filed.

So what, old chum?" (Strange lines beyond my scansion.)

A girl so sweet, if woebegone?

Why, surely she was everyone’s!

He lifts his eyes, shifts, sighs, spits, unbeguiled.

He does not know that I have come to judge him.

"What’s it to you?" he threatens, with a leer.

She was my child . . .

"That

thing defiled?"

Ten trillion wavering stars blink, disappear.

Suffer the Little Children

by Nakba

I saw the carnage . . .

saw girls' dreaming heads

blown to red atoms,

and their dreams with them . . .

. . .

saw babies liquefied

in burning beds

as, horrified,

I heard their murderers’ phlegm . . .

I saw my mother stitch

my shroud’s black hem,

for in that moment

I was one of them . . .

I saw our Father’s eyes

grow hard and bleak

to see frail roses severed at the stem . . .

How could I fail to speak?

Lines for a Palestinian Mother and Child

by Nakba

I swear her eyes were gentle . . . that she was

a child herself, although she bore a child

close to her breast: her one and only cause.

I watched in apprehension as men filed

in close, goose-stepping ranks on either side,

as if they longed for blood, on Eastertide.

I thought of women slain for being born

the "wrong" race, sex, caste, or the "wrong" religion.

I thought of Joan of Arc, her tunic torn,

her breasts exposed, her bloody Inquisition.

I felt the flames and then her screams explode.

I thought of Mary and her dolorous road.

When will religion learn men must repent

of killing even one mild innocent—

whether

before or after Lent?

Lockheed, Take Heed

by Nakba

Terror fell upon my children. Wailing,

they ran toward my arms—small, pale with fright.

They seemed eternities from me . . . so distant!

Their day exploded. Now I live in night.

"Made in America." I find that tragic.

Though far less tragic than my sweet doves, blown

to atoms by your profits’ ill-bought magic.

Land of the "brave," the "free"? Brave freedom’s flown

to heights unknown—too high to see my people

crushed in the dust by those you love so well.

Sing hymns. Praise God. Erect some higher steeple.

Condemn my kind to poverty, and hell.

"Shock and awe?" Yes, I feel awe—and shock.

You jackals killed my doves, my lambs, my flock!

US Schoolboys

by Nakba

The simple path to peace

begins with a single step,

as the sun breaks bright to the East

though the schoolboy has long overslept.

O, when will he rise and yawn!

Will he miss how dew spangles the lawn?

The simple peace path begins

when the schoolboy repents of his sins,

for his balmy vacation’s long over.

There’s no time to be lolling in clover!

Now that the bright day has begun,

he must rise in accord with the sun.

The path is called Justice . . . and now

he must walk it, and stoutly avow

to follow wherever it leads

till the sun sets its blaze to the weeds . . .

He must thresh, so his brothers can find

peace’s path, though the world seems blind.

Her Slender Arm

by Nakba

Her slender arm, her slender arm,

I see it reaching out to me!—

wan, vulnerable, without a charm

or amulet to guard it. Flee!

I scream at her in wild distress.

She chides me with defiant eyes.

Where shall I go? They scream, "Confess!

Confess yourself, your children lice,

your husband mantis, all your kind

unfit to live!"

See, or be blind.

I cannot see beyond the gloom

that shrouds her in their terrible dungeon.

I only see the nightmare room,

the implements of torture.

Sudden

shocks contort her slender frame!

She screams, I scream, we scream in pain!

I sense the shadow-men, insane,

who gibber, drooling, Why are you

not just like US, the Chosen Few?

Suddenly, she stares through me

and suddenly I understand:

I hear the awful litany

of names I voted for. My hand

lies firmly on the implement

they plan to use, next, on her children

who huddle in the corner. Bent,

their bidden pawn, I heil Amen!

to their least wish. I hone the blade

"Made in America," their slave.

She has no words, but only tears.

I turn and retch. I vomit bile.

I hear the shadow men’s cruel jeers.

I sense, I feel their knowing smile.

I paid for this. I built this place.

The little that she had, they took

at my expense. Now they erase

her family from life’s tattered book.

I cannot meet her eyes again.

I stand one with the shadow men.

In her dread repose (I)

by Nakba

Find in her pallid, dread repose—

no hope, alas!, for the Rose.

In her dread repose (II)

by Nakba

Find in her pallid, dread repose—

no hope for the World. O, my violated Rose!

The Least of These

by Nakba

Here lies a child of the Holocaust.

And here all her dreams lie buried, unknown . . .

lie buried, unlived. And who knows the cost?

No roses grow here by this stone

stark as bone.

"Dearly Beloved," her white marker reads,

as many bright sermons on Love have begun,

but this is her end. She lies among weeds

more somber than widows’

six feet from the sun.

Whom shall we cherish? O, whom shall we love?

The war profiteer, or the peaceable dove?

"Made in America," this Cruise Line said:

now Palestine’s dove lies here—cold, shattered, dead.

Here lie her pieces. Friend, read them, and weep.

Stand firmly for justice, or lie in your sleep.

The Horror

by Nakba

the Horror is a child who died because

we closed our eyes to tribal Nature’s laws,

who knows no justice, but red fangs and claws

the Horror is the child we led to stray

into dark wilds where evil Men hold sway,

abandoned her, then swiftly walked away

now she lies dead, and many innocents!

the Tiger prowls; He longs to kill; He pants

for blood, as children die, unheard, like ants

the Tiger rules by Law, red Claw and Tooth,

while Barnums laugh, count Beans, and sip Vermouth.

I Saw

by Nakba

I saw the carnage . . .

saw their dreaming heads

blown to red atoms,

and their dreams with them.

I saw their fathers’ eyes

grow hard and bleak,

as did my own.

I heard their murderers’ phlegm.

I saw them in my dreams;

my knees grew weak . . .

for in that moment I was one of them . . .

How could I fail to speak?

The BOSS

by Nakba

In 1948,

crying "Holocaust!"

the Jews became the keepers

and mad sweepers of the lost

doomed

Palestinian nation,

while every American "Christian"

wept with great elation

to see Yahweh’s "salvation."

He’s the BOSS!

Though He couldn’t take on Hitler,

though Himmler had Him harried,

though Goering had Him groping

for answers—yes, and worried—

though Mengele had mangled

the fairest and the brightest

of all His chosen tribes

and those with whom He’s tightest . . .

He’s the BOSS!

Forget all human justice.

Forget about two wrongs.

Just ply the LORD with money,

pleas, prayers and fervent songs.

Then let the children suffer

and let the strong run wild.

You’re in with heaven’s Duffer!

Your prayers have Him beguiled!

So ... You’re the BOSS!

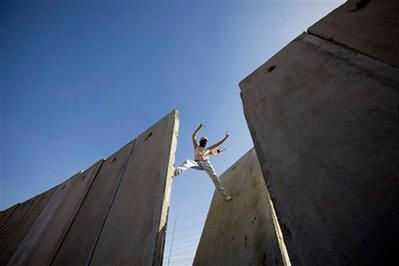

Stampede

by Nakba

I dreamt last night I was a Palestinian

herded like a cow or a defeated Indian

down some new Trail of Tears, into Gaza’s corral.

And I dreamt that you watched me

from the highest Wall.

I dreamt the whip cracked; how it bit my flesh!

I was gaunter than the skeletons of Bangladesh.

But I stood straight, upright. I refused to fall.

And I dreamt that you watched me

from the highest Wall.

I screamed aloud, but I refused to break

though my geysering blood created red lakes.

My oppressors laughed, Nazis!, but I stood tall.

And I dreamt that you watched me

from the highest Wall.

O, when will you see me, and meet my eye?

O, when will you hear me, and regard my cry?

You put me here. You helped build this cursed Wall

with your nickels and your dimes and your pious calls

for "democracy" and "freedom." How your voice appalls!

Now we mill here like cattle, in our abattoir stalls.

It was you who interred us. Please, before it’s too late,

break down the fucking wall, fling open hell’s gate!

Amen

DISCLOSURE: The Palestinian poet Nakba is an alias of the American poet Michael

R. Burch, who also writes as "The Children of Gaza" in order to give voiceless

children a voice.

Michael R. Burch Main Translation Page & Index:

The Best Poetry Translations of Michael R. Burch

The Best Poetry Translations of Michael R. Burch (sans links)

Translation Pages by Language:

Modern English Translations of Anglo-Saxon Poems by Michael R. Burch

Modern English Translations of Middle English and Medieval Poems

English Translations of Arabic/Palestinian Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of Chinese Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of Female Chinese Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of French Poets by Michael R. Burch

Germane Germans: English Translations by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of German Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of Japanese Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of Japanese Zen Death Poems

English Translations of Ancient Mayan Love Poems

English Translations of Native American Poems, Proverbs and Blessings

English Translations of Roman, Latin and Italian Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of Tamil Poets

English Translations of Urdu Poets by Michael R. Burch

English Translations of Uyghur Poets by Michael R. Burch

Translation Pages by Poet:

Catullus Translations by Michael R. Burch

Ovid Translations by Michael R. Burch

Leonardo da Vinci Translations by Michael R. Burch

Pablo Neruda Translations by Michael R. Burch

The HyperTexts