The HyperTexts

Whither Formalism?

by Michael R. Burch

After the death of Seamus Heaney, will contemporary

formal/traditional poetry wither on the vine, or will it continue to flourish?

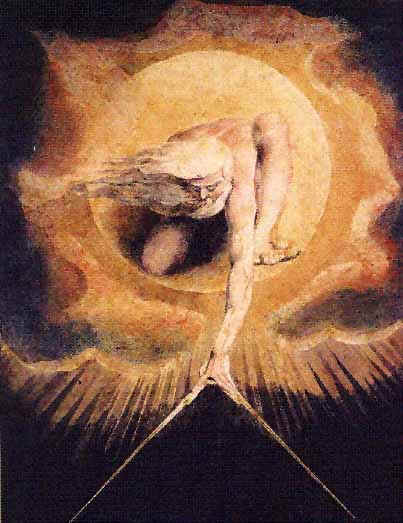

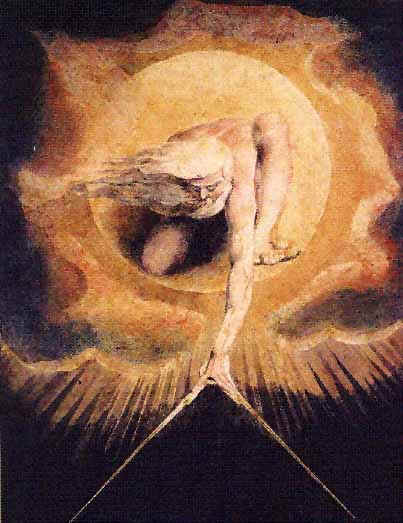

William Blake's "Ancient of Days"

The death of Seamus Heaney on Friday, August 30, 2013 caused me to pause

and reflect on the current "state of the art" of contemporary formalism, and of

poetry in general. Was Heaney, who at one point was the author of a third of all

the poetry books sold in England, the last superstar of modern English poetry? Will

there ever be another? If poetry remains viable in the 21st century, will there

be a place for formal/traditional poetry? If so,

will it be a place of honor, or just a tiny, dark, neglected niche?

I think the honest answers are "no one really knows" and "it all depends (on the

talent, genius and craftsmanship of poets)." But I remain hopeful, even

optimistic, because I think it's obvious that excellent formal/traditional

poetry continues to be written, and often to be

read, despite the obvious angst of poets who insist that

readers have abandoned them; ... is it possible that they only abandoned the duller,

more tedious poets?

While I could write at length about the obvious attractions of traditional

poetry, with its ear- and heart-pleasing meter and rhyme, it seems wiser to me

to let the better poems and poets speak for themselves. As an editor and

publisher of poetry, I have long operated on the premise that only the best

poems really matter, in the long run. So here, without further

ado, are my causes for not-so-cautious optimism ...

The Forge

by Seamus Heaney

All I know is a door into the dark.

Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting;

Inside, the hammered anvil’s short-pitched ring,

The unpredictable fantail of sparks

Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water.

The anvil must be somewhere in the centre,

Horned as a unicorn, at one end and square,

Set there immoveable: an altar

Where he expends himself in shape and music.

Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose,

He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter

Of hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows;

Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick

To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

The Death of a Toad

by Richard Wilbur

A toad the power mower caught,

Chewed and clipped of a leg, with a hobbling hop has got

To the garden verge, and sanctuaried him

Under the cineraria leaves, in the shade

Of the ashen and heartshaped leaves, in a dim,

Low, and a final glade.

The rare original heartsblood goes,

Spends in the earthen hide, in the folds and wizenings, flows

In the gutters of the banked and staring eyes. He lies

As still as if he would return to stone,

And soundlessly attending, dies

Toward some deep

monotone,

Toward misted and ebullient seas

And cooling shores, toward lost Amphibia's emperies.

Day dwindles, drowning and at length is gone

In the wide and antique eyes, which still appear

To watch, across the castrate lawn,

The haggard

daylight steer.

I can't remember where or when I first read "The Death of a Toad," but

the poem haunted me until I finally rediscovered it many years later, while flipping through

the pages of a poetry anthology in a Nashville bookstore. I had forgotten the poem's title

and who wrote it, but I had never been able to forget its words' magic.

I believe Richard Wilbur made himself immortal with this one.

Lullaby

by W. H. Auden

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm:

Time and fevers burn away

Individual beauty from

Thoughtful children, and the grave

Proves the child ephemeral:

But in my arms till break of day

Let the living creature lie,

Mortal, guilty, but to me

The entirely beautiful.

Soul and body have no bounds:

To lovers as they lie upon

Her tolerant enchanted slope

In their ordinary swoon,

Grave the vision Venus sends

Of supernatural sympathy,

Universal love and hope;

While an abstract insight wakes

Among the glaciers and the rocks

The hermit's carnal ecstacy.

Certainty, fidelity

On the stroke of midnight pass

Like vibrations of a bell

And fashionable madmen raise

Their pedantic boring cry:

Every farthing of the cost.

All the dreaded cards foretell.

Shall be paid, but from this night

Not a whisper, not a thought.

Not a kiss nor look be lost.

Beauty, midnight, vision dies:

Let the winds of dawn that blow

Softly round your dreaming head

Such a day of welcome show

Eye and knocking heart may bless,

Find our mortal world enough;

Noons of dryness find you fed

By the involuntary powers,

Nights of insult let you pass

Watched by every human love.

Auden famously said that poetry makes nothing happen, but Auden's poetry makes good things happen

inside me. I find it

interesting that poets as different as Blake and Auden wrote two of the most

wonderfully tender lullabies in the English language: one for a baby, one for a

lover.

For Her Surgery

by Jack Butler

I

Over the city the moon rides in mist,

scrim scarred with faint rainbow.

Two days till Easter. The thin clouds run slow, slow,

the wind bells bleed the quietest

of possible musics to the dark lawn.

All possibility we will have children is gone.

II

I raise a glass half water, half alcohol,

to that light come full again.

Inside, you sleep, somewhere below the pain.

Down at the river, there is a tall

ghost tossing flowers to dark water—

jessamine, rose, and daisy, salvia lyrata . . .

III

Oh goodbye, goodbye to bloom in the white blaze

of moon on the river, goodbye

to creek joining the creek joining the river, the axil, the Y,

goodbye to the Yes of two Ifs in one phrase . . .

Children bear children. We are grown,

and time has thrown us free under the timeless moon.

This has long been one of my favorite poems by a contemporary poet. When people

bemoan the "state of the art," I think of poems like this one and find

scant

cause for concern.

The Ghost Ship

by A. E. Stallings

She plies an inland sea. Dull

With rust, scarred by a jagged reef.

In Cyrillic, on her hull

Is lettered, Grief.

The dim stars do not signify;

No sonar with its eerie ping

Sounds the depths—she travels by

Dead reckoning.

At her heart is a stopped clock.

In her wake, the hours drag.

There is no port where she can dock,

She flies no flag,

Has no allegiance to a state,

No registry, no harbor berth,

Nowhere to discharge her freight

Upon the earth.

A. E. Stallings is a contemporary poet who's making a name for herself, and

leaving her mark on the world in the form of memorable poems.

Sea Fevers

by Agnes Wathall

No ancient mariner I,

Hawker of public crosses,

Snaring the passersby

With my necklace of albatrosses.

I blink no glittering eye

Between tufts of gray sea mosses

Nor in the high road ply

My trade of guilts and glosses.

But a dark and inward sky

Tracks the flotsam of my losses.

No more becalmed to lie,

The skeleton ship tosses.

While few readers may have heard of Agnes Wathall, her "Sea Fevers" is a poem that demands remembering.

Bread and Music

by Conrad Aiken

Music I heard with you was more than music,

And bread I broke with you was more than bread;

Now that I am without you, all is desolate;

All that was once so beautiful is dead.

Your hands once touched this table and this silver,

And I have seen your fingers hold this glass.

These things do not remember you, belovčd,

And yet your touch upon them will not pass.

For it was in my heart you moved among them,

And blessed them with your hands and with your eyes;

And in my heart they will remember always,—

They knew you once, O beautiful and wise.

In his best poems

Conrad Aiken rivals W. H. Auden, Dylan Thomas, Wallace Stevens and Hart Crane as

masters of modern English poetic meter. Aiken's "Bread and Music" is one of my

favorite poems, regardless of era.

Depths

by Richard Moore

Once more home is a strange place: by the ocean a

big house now, and the small houses are memories,

once live images, vacant

thoughts here, sinking and vanishing.

Rough sea now on the shore thundering brokenly

draws back stones with a roar out into quiet and

far depths, darkly to lie there

years, years—there not a sound from them.

New waves out of the night's mist and obscurity

lunge up high on the beach, spending their energy,

each wave angrily dying,

all shapes endlessly altering,

yet out there in the depths nothing is modified.

Earthquakes won't even move—no, nor the hurricane—

one stone there, nor a glance of

sun's light stir its identity.

This is a wonderfully haunting poem by the contemporary poet Richard Moore, who

lived in a dilapidated mansion close by the sea, until his death.

Friday

by Ann Drysdale

The print of a bare foot, the second toe

A little longer than the one which is

Traditionally designated "great".

Praxiteles would have admired it.

You must have left in haste; your last wet step

Before boarding your suit and setting sail,

Outlined in talcum on the bathroom floor

Mocks your habitual fastidiousness.

There is no tide here to obliterate

Your oversight. Unless I wipe or sweep

Or suck it up, it will not go away.

The thought delights me. I will keep the footprint.

Too slight, too simply human to be called

Token or promise; I am keeping it

Because it is a precious evidence

That on this island I am not alone.

Ann Drysdale is one of the better contemporary poets I've had the honor and

pleasure of publishing. Her poem "Friday" evinces a keen eye, irony, humor and

something of a child's sense of wonder.

Come Lord and Lift

by T. Merrill

Come Lord, and lift the fallen bird

Abandoned on the ground;

The soul bereft and longing so

To have the lost be found.

The heart that cries—let it but hear

Its sweet love answering,

Or out of ether one faint note

Of living comfort wring.

This poem (the poet is an atheist) seems to be both an earnest, heartfelt prayer

and a condemnation of religion's dubious "God." Why doesn't he have

compassion on fallen birds, one wonders, and use all his lauded superpowers to

help them? . . .

Plea

by

Leslie Mellichamp

O singer, sing to me—

I know the world's awry—

I know how piteously

The hungry children cry—

But I bleed warm and near,

And come another dawn

The world will still be here

When home and hearth are gone.

Formal poetry lost a staunch advocate when Leslie Mellichamp died on

December 18, 2001. Editor of The Lyric, the oldest magazine in North

America devoted to traditional poetry, he was the author of scores of poems,

essays, and short stories that appeared in the 1950s and '60s in such places as

the Atlantic, New York Times, Saturday Review, Ladies'

Home Journal, and the Georgia Review. Believing with the gifted

contributors who have kept The Lyric alive since 1921 that the roots of a

living poetry lie in music and the common life, rather than in the fragmented

bizarre, and that rhyme, structure, and lucidity are timeless attributes of

enduring poetry, he offered his own lyrics as tributes to life's ancient

ironies, the earth's patient resilience, the impudence of lovers, the wondrous

eyes of children, and the cunning of that soft-shoed thief, Time. Below are a

few of Leslie Mellichamp's poems, would that there had been more.

Rondel

by Kevin N.

Roberts

Our time has passed on swift and careless feet,

With sighs and smiles and songs both sad and sweet.

Our perfect hours have grown and gone so fast,

And these are things we never can repeat.

Though we might plead and pray that it would last,

Our time has passed.

Like shreds of mist entangled in a tree,

Like surf and sea foam on a foaming sea,

Like all good things we know can never last,

Too soon we'll see the end of you and me.

Despite the days and realms that we amassed,

Our time has passed.

Kevin Nicholas Roberts [1969-2008] was a poet, fiction writer

and professor of English Literature. He died on December 10, 2008. Kevin

had lived and studied all over the United States and had also spent three

years in the English countryside of Suffolk writing Romantic poetry and

studying the Romantic Masters beside the North Sea. His poetry has been

compared to that of Swinburne, one of his major influences. Kevin was

born on the 4th of April in the United States, which, accounting for the hour of

his birth and the time zone difference, just happened to be Swinburne's

birthdate, April the 5th, in England. And he told me once that he believed he

was the reincarnation of Swinburne.

First Confession

by X. J.

Kennedy

Blood thudded in my ears. I scuffed,

Steps stubborn, to the telltale booth

Beyond whose curtained portal coughed

The robed repositor of truth.

The slat shot back. The universe

Bowed down his cratered dome to hear

Enumerated my each curse,

The sip snitched from my old man's beer,

My sloth pride envy lechery,

The dime held back from Peter's Pence

with which I'd bribed my girl to pee

That I might spy her instruments.

Hovering scale-pans when I'd done

Settled their balance slow as silt

While in the restless dark I burned

Bright as a brimstone in my guilt

Until as one feeds birds he doled

Seven our Fathers and a Hail

Which I to double-scrub my soul

Intoned twice at the altar rail

Where Sunday in seraphic light

I knelt, as full of grace as most,

And stuck my tongue out at the priest:

A fresh roost for the Holy Ghost.

I have absolutely loved this poem by X. J. Kennedy since the day I first read

it. I agonized with the boy during his shameful forced confession and delighted

at his

truant tongue's triumphant revenge.

Compass Rose

by Jennifer Reeser

I'd buy you a Babushka doll, my heart,

and brush your ash-blonde hair until it gleams,

were Russia and our land not laid apart

by ocean so much deeper than it seems.

I have an oval pin, though—glossy lacquer

hand-made in Moscow, after glasnost came,

with fine, deft roses on a background blacker

perhaps, than history's collective shame.

I've done my best to compass you with roses:

the tablecloth, the walls, the pillowcase,

the western side-yard only dusk discloses

briefly, in Climbing Blaze and Queen Anne's lace.

May they suffice for peace when you discover

your love is not enough to turn the earth.

I dream I saw a handful of them hover

against my pane the morning of your birth.

The Lovemaker

by Robert Mezey

I see you in her bed,

Dark, rootless epicene,

Where a lone ghost is laid

And other ghosts convene;

And hear you moan at last

Your pleasure in the deep

Haven of her who kissed

Your blind mouth into sleep.

But body, once enthralled,

Wakes in the chains it wore,

Dishevelled, stupid, cold,

And famished as before,

And hears its paragon

Breathe in the ghostly air,

Anonymous carrion

Ravished by despair.

Lovemaker, I have felt

Desire take my part,

But lacked your constant fault

And something of your art,

And would not bend my knees

To the unmantled pride

That left you in that place,

Forever unsatisfied.

This is another of my favorite poems by a contemporary poet. Other poems by Robert Mezey appear elsewhere on this page.

Miscarried

by Rhina P.

Espaillat

Blind little fish baffled but not quite

caught in the net of our need, what did you taste

in us that compelled you to cheat the tide

of our biography? Minutest beast

caged by our blood’s unwisdom, what clever

stratagem so undid you that, done out

of you, we stand at the coast of Never

to bid you this farewell? Least cosmonaut

loosed from the look of us as from a suit

of time’s weaving, in what pure alien form

did you slip home again across those mute

light years to nothing, missing and still warm?

Rhina Espaillat is that rarest of creatures: a good poet who is an even better

person.

The Missionary's Position

by Joseph S. Salemi

I maintain it all was for the best—

We hacked our way through jungle and sought out

These savage children, painted and half-dressed,

To set their minds at ease, and dispel doubt.

Concerning what? Why, God's immense design,

And how it governs all we do and see.

Before, they had no sense of the divine

Beyond the sticks and bones of sorcery.

Granted, they are more somber and subdued,

Knowing that lives are watched, and judged, and weighed.

Subject to fits of melancholy mood,

They look upon the cross, and are afraid.

What would you have me say? We preached the Word

Better endured in grief than left unheard.

This is a poem that ought to cure "Christian" missionaries of their evangelistic

zeal, if only they had hearts capable of compassion for the children they

terrorize, and brains capable of reason. I have long admired this powerful poem,

written by a contemporary Catholic poet.

from Word from the Hills

a sonnet sequence in four movements

by Richard Moore

11

You were so solid, father, cold and raw

as these north winters, where your angry will

first hardened, as the earth when the long chill

deepens—as is this country's cruel law—

yet under trackless snow, without a flaw

covering meadow, road, and stubbled hill,

the springs and muffled streams were running still,

dark until spring came, and the awful thaw.

In your decay a gentleness appears

I hadn't guessed—when, gray as rotting snow,

propped in your chair, your face will run with tears,

trying to speak, and your hand, stiff and slow,

will touch my child—who, sensing the cold years

in your eyes, cries until you let her go.

This poem by the contemporary poet Richard Moore about his father and daughter

proves that real life can be darker and more frightening than any horror story.

Willy Nilly

by

Michael R. Burch

for the Demiurge aka Yahweh/Jehovah

Isn’t it silly, Willy Nilly?

You made the stallion,

you made the filly,

and now they sleep

in the

dark earth, stilly.

Isn’t it silly, Willy Nilly?

Isn’t it silly, Willy Nilly?

You forced them to run

all their days

uphilly.

They ran till they dropped—

life’s a pickle, dilly.

Isn’t it silly, Willy Nilly?

Isn’t it silly, Willy Nilly?

They say I should worship you!

Oh, really!

They say I should pray

so you’ll not act illy.

Isn’t it silly, Willy Nilly?

While some aspiring intellectuals might turn up their noses at this poem of

mine, sniffing and calling it "doggerel," I think it makes a point similar to

Tom Merrill's, in a humorous way. If God is all-loving, all-wise and all-just,

why do people have to pray so diligently to him not to act unlovingly, unwisely

and unjustly?

Forgive, O Lord

by Robert Frost

Forgive, O Lord, my little jokes on Thee

And I'll forgive the great big one on me.

I believe Robert Frost harbored similar doubts, reservations, disillusionments,

etc., about God, the Bible and Christianity.

Excerpts from "More Poems," XXXVI

by A. E. Housman

Here dead lie we because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

The poem above was the first ever to appear on the pages of The HyperTexts.

I believe Housman's lines disprove many of the modern mantras that

seem to accompany poetry the way dark clouds accompany lightning: "no ideas but in things," "make

it new (because normal speech is 'unoriginal' and the poetic tradition is toast)," "rhyme is passé," "meter is passé,"

"the perfect poem is silence," etc. But Housman's lines also disprove certain ancient dogmas about poetry as

well, such as the one about metaphor being the be-all and end-all of poetry.

Housman, like Shakespeare, was a master of direct statement. The great soliloquies

of Hamlet are not metaphors but abstract examinations of the human condition, from the perspective of

the ego. Poetry is the realm of the abstract as well as the concrete, and of all

forms of speech from plainspoken directness to surrealistic phantasmagoria. Great poets can pull off almost anything, and make readers

glad they did. So as you read the poems on this page, please feel free to

lean back, relax and escape the tedium of theories about poetry, for

the true joys of the most en-chant-ing of the Muses.

The Examiners

by John Whitworth

Where the house is cold and empty and the garden’s overgrown,

They are there.

Where the letters lie unopened by a disconnected phone,

They are there.

Where your footsteps echo strangely on each moonlit cobblestone,

Where a shadow streams behind you but the shadow’s not your own,

You may think the world’s your oyster but it’s bone, bone, bone:

They are there, they are there, they are there.

They can parse a Latin sentence; they’re as learned as Plotinus,

They are there.

They’re as sharp as Ockham’s razor, they’re as subtle as Aquinas,

They are there.

They define us and refine us with their beta-query-minus,

They’re the wall-constructing Emperors of undiscovered Chinas,

They confine us, then malign us, in the end they undermine us,

They are there, they are there, they are there.

They assume it as an impost or they take it as a toll,

They are there.

The contractors grant them all that they incontinently stole,

They are there.

They will shrivel your ambition with their quality control,

They will desiccate your passion, then eviscerate your soul,

Wring your life out like a sponge and stuff your body down a hole,

They are there, they are there, they are there.

In the desert of your dreaming they are humped behind the dunes,

They are there.

On the undiscovered planet with its seven circling moons,

They are there.

They are ticking all the boxes, making sure you eat your prunes,

They are sending secret messages by helium balloons,

They are humming Bach cantatas, they are playing looney tunes,

They are there, they are there, they are there

They are there, they are there like a whisper on the air,

They are there.

They are slippery and soapy with our hope and our despair,

They are there.

So it’s idle if we bridle or pretend we never care,

If the questions are superfluous and the marking isn’t fair,

For we know they’re going to get us, we just don’t know when or where,

They are there, they are there, they are there.

According to one appreciative critic, "John Whitworth's poems are as smart and

full of fun as a pair of glazed tap shoes. He is a wise rueful virtuoso." Having

read "The Examiners," how can we fail to agree?

The Poem of Poems

by Greg Alan Brownderville

A boy passes ghost-like through a curtain of weeping willow.

In rainbow-stained apparel, birds are singing a cappella.

Suddenly I sense it, in the birds and in the child:

The world is a poem growing wild.

A dewdrop on a blade of grass soon slips from where it clung

Like a perfect word that gathers on the tip of a poet's tongue.

And men are merely characters to love and be defiled.

God is a poem growing wild.

This is a fine contemporary poem in the mystic tradition of Blake and Whitman.

Jack Butler and Greg Brownderville are both "Arkansas" boys . . . there must be

something in the water down there, or perhaps it's in the mayhaw jelly.

Piano

by D. H. Lawrence

Softly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;

Taking me back down the vista of years, till I see

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom of the tingling strings

And pressing the small, poised feet of a mother who smiles as she sings.

In spite of myself, the insidious mastery of song

Betrays me back, till the heart of me weeps to belong

To the old Sunday evenings at home, with winter outside

And hymns in the cozy parlor, the tinkling piano our guide.

So now it is vain for the singer to burst into clamor

With the great black piano appassionato. The glamour

Of childish days is upon me, my manhood is cast

Down in the flood of remembrance, I weep like a child for the past.

While Modernism sometimes makes a fetish out of imagism, this

poem shows how effectively images can be used in the hands of a genius who is

also a skilled craftsman. It's hard to imagine a more perfectly drawn or more

moving poem.

The Man Whose Pharynx Was Bad

by Wallace Stevens

The time of year has grown indifferent.

Mildew of summer and the deepening snow

Are both alike in the routine I know:

I am too dumbly in my being pent.

The wind attendant on the solstices

Blows on the shutters of the metropoles,

Stirring no poet in his sleep, and tolls

The grand ideas of the villages.

The malady of the quotidian . . .

Perhaps if summer ever came to rest

And lengthened, deepened, comforted, caressed

Through days like oceans in obsidian

Horizons, full of night's midsummer blaze;

Perhaps, if winter once could penetrate

Through all its purples to the final slate,

Persisting bleakly in an icy haze;

One might in turn become less diffident,

Out of such mildew plucking neater mould

And spouting new orations of the cold.

One might. One might. But time will not relent.

Wallace Stevens is a wonder, and an enigma. It's hard to say what he believed,

if he believed anything. Like another famous W. S., he seems somehow subsumed in

his work. But regardless of what he believed, or didn't, he wrote some of the

most gorgeous poems of the modern era, or any era.

The Old Lutheran Bells at Home

by Wallace Stevens

These are the voices of the pastors calling

In the names of St. Paul and of the halo-John

And of other holy and learned men, among them

Great choristers, propounders of hymns, trumpeters,

Jerome and the scrupulous Francis and Sunday women,

The nurses of the spirit's innocence.

These are the voices of the pastors calling

Much rough-end being to smooth Paradise,

Spreading out fortress walls like fortress wings.

Deep in their sound the stentor Martin sings.

Dark Juan looks outward through his mystic brow . . .

Each sexton has his sect. The bells have none.

These are the voices of the pastors calling

And calling like the long echoes in long sleep,

Generations of shepherds to generations of sheep.

Each truth is a sect though no bells ring for it.

And the bells belong to the sextons, after all,

As they jangle and dangle and kick their feet.

I love the last stanza of this poem, which makes it sounds as if the sextons have

lost control and are being swung about by the bells, having become human

"clappers."

Madame LaBouche

by T. Merrill

Her ears pricked up so much, Madame

LaBouche, decrying all disturbance

Insisted sounds around be less

City-like and more suburban.

One bistro gave Madame no rest

Until it was at last subdued,

And vexed by yakky cabbies next,

She finally got their stand removed.

Yet still, some night-owl might abort

The dreamshift of LaBouche's week,

And pop her prized unconsciousness

By passing with a piercing shriek,

Or other nuisances emerge—

But when, for my part, out a window

I spot Madame surveying things,

Hard eye a-gleam, arms set akimbo

All poised to nail some passerby

With shrill bursts from her magic flute—

I see the sole noisemaker I

Have lately dreamed of going mute.

Tom Merrill is one of my favorite contemporary poets. Like Ann Drysdale, he has

a keen eye for detail and a wonderful sense of irony. He also has something of a

Swiftian loathing for fools and hypocrites (especially the "Christian" kind,

who so often seem more concerned about other people's morals than their own).

Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae

by Ernest Dowson

"I am not as I was under the reign of the good Cynara"—Horace

Last night, ah, yesternight, betwixt her lips and mine

There fell thy shadow, Cynara! thy breath was shed

Upon my soul between the kisses and the wine;

And I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, I was desolate and bowed my head:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

All night upon mine heart I felt her warm heart beat,

Night-long within mine arms in love and sleep she lay;

Surely the kisses of her bought red mouth were sweet;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

When I awoke and found the dawn was gray:

I have been faithful to you, Cynara! in my fashion.

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost lilies out of mind;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, all the time, because the dance was long;

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I cried for madder music and for stronger wine,

But when the feast is finished and the lamps expire,

Then falls thy shadow, Cynara! the night is thine;

And I am desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, hungry for the lips of my desire:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

Ernest Dowson wrote a small handful of poems that are among the strongest in the

English language. I consider him one of the very best "unknown" or

"under-known" major poets, along with Louise Bogan. The poem above should make

him forever immortal, unless readers lose their ears and their senses.

Dulce Et Decorum Est

by Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime...

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

"Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" appears in Horace's Odes.

The "old lie" means: "It is sweet and fitting

to die for one's country." Wilfred Owen stands at the vanguard of the great

anti-war poets and singer-songwriters. "Dulce Et Decorum Est" may be the most

important poem in the English language: one that eventually leads to the

abolition of war. But in any case, Wilfred Owen was undoubtedly a major poet,

and one of the first great truly modern English poets. He died just before the

armistice that ended World War I. There's no telling what he might have

accomplished if he had lived, but he left behind a good number of immortal

poems: all of them penned within the short period of time between his enlistment

and death.

Development

by

Maryann Corbett

This is your deed. Its words

impose restrictions.

You leave behind unruly nether worlds

of noisy rental neighborhoods,

landlords, evictions,

leave the wheezings of pipes, the fluorescent hummings,

the homeless houseplants on the fire escape,

the boots on stairs, the goings at all hours

(and, through thin walls, the comings).

You leave the crime-scene tape

for greater safety. Here the Association

will help you set the tone we all depend on

for distancing the stranger.

Let us design your plantings: rhododendron,

white iris, blue hydrangea.

Clotheslines? No. Dismiss the metaphor

of linen angel-visions buoyed with air,

first light gilding their raiment.

Keep to this earth (set forth hereinbefore),

this mortgage payment.

Why such resistance?

Peace has a certain cost. What we demand

does not pass understanding; understand

perspective that maintains a middle distance.

Seize what you can

of Order, its exterior colors pale,

historically correct, Augustan, cool.

See how it sets its face

implacably against the threatening weather.

Its covenants are righteous altogether.

Sign here. And keep your name inside the space.

Maryann Corbett is the author of two chapbooks,

Dissonance and Gardening in a Time of War. She is a co-winner of the 2009 Willis

Barnstone Translation Prize, and her poems, essays, and translations have

appeared or are forthcoming in River Styx,

Atlanta Review, The Evansville Review, Measure, The Lyric, Candelabrum, First Things,

Blue Unicorn, The Raintown Review, Christianity and Literature, The Dark Horse, The Barefoot Muse, Unsplendid,

and other journals in print and online. Since 2008 she has served as the administrator of Eratosphere, a popular online

forum for poets, especially those specializing in metrical verse.

The Eagle and the Mole

by Elinor Wylie

Avoid the reeking herd,

Shun the polluted flock,

Live like that stoic bird,

The eagle of the rock.

The huddled warmth of crowds

Begets and fosters hate;

He keeps above the clouds

His cliff inviolate.

When flocks are folded warm,

And herds to shelter run,

He sails above the storm,

He stares into the sun.

If in the eagle's track

Your sinews cannot leap,

Avoid the lathered pack,

Turn from the steaming sheep.

If you would keep your soul

From spotted sight or sound,

Live like the velvet mole:

Go burrow underground.

And there hold intercourse

With roots of trees and stones,

With rivers at their source,

And disembodied bones.

This is wonderfully scary poem by a poet who is under-known and

under-appreciated today. One can seldom trust the "advice" of poets. If I

apprehend the wily Wylie correctly, it seems she offers us three options: (1) the dubious

warmth of the reeking herd, (2) the alien loneliness of the aloof eagle, or (3)

the blind burrowing of the velvet mole.

La Figlia Che Piange (The Weeping Girl)

by T. S. Eliot

Stand on the highest pavement of the stair —

Lean on a garden urn —

Weave, weave the sunlight in your hair —

Clasp your flowers to you with a pained surprise —

Fling them to the ground and turn

With a fugitive resentment in your eyes:

But weave, weave the sunlight in your hair.

So I would have had him leave,

So I would have had her stand and grieve,

So he would have left

As the soul leaves the body torn and bruised,

As the mind deserts the body it has used.

I should find

Some way incomparably light and deft,

Some way we both should understand,

Simple and faithless as a smile and a shake of the hand.

She turned away, but with the autumn weather

Compelled my imagination many days,

Many days and many hours:

Her hair over her arms and her arms full of flowers.

And I wonder how they should have been together!

I should have lost a gesture and a pose.

Sometimes these cogitations still amaze

The troubled midnight, and the noon's repose.

When T. S. Eliot began to write, modern poetry began to change. Harold Bloom has

suggested that Shakespeare invented the modern human being. I would venture to say that T. S. Eliot

invented the modern poet (pale, introverted, fastidious, self-absorbed and

therefore endlessly dismayed) when he portrayed himself as Prufrock in "The Love

Song of J. Alfred Prufrock." Why poets want to be, or feel obliged to be, like

Prufrock, I have no idea. But that many of them are Prufrocks seems beyond question.

Perhaps they misread the poem and believed Prufrock ended up with the girls, or

the mermaids . . .

Part 6 from The Dark Side of the Deity: Interlude

by

Joe M. Ruggier

When Satan hurled, before the Dawn,

defiance at the Lord of History;

and Michael stood, and Glory shone,

Whose hand controlled the timeless Mystery?

Who but the Insult was the leveler;

Deliverer and bedeviler?

When Athens, sung in verse and prose,

caught all the World's imagination;

when Ilion fell, and Rome arose,

and Time went on like pagination:

Who but the Insult was the leveler;

Deliverer and bedeviler?

When books, in numberless infinities,

cross-fertilize the teeming brain,

and warring, vex the Soul with Vanities,

and Insults hurtle, Insults rain:

Who but the Insult is the leveler;

Deliverer and bedeviler?

And when we too shall cease to be,

like all the Kingdoms of the Past,

and groaning, gasping, wrenching free,

we bite, at last, alone, the dust:

Who but the Insult is the leveler;

Deliverer and bedeviler?

When church‑bells fill the wandering fields

with Love and Fear,

the Flesh and Blood of Jesus yields

deliverance dear,

to them who believe in the Compliment Sinsear.

Joe Ruggier is quite a story, having sold over 20,000 books by going

door-to-door. He is a Maltese poet who now lives in British Columbia.

Sarabande on Attaining the Age of Seventy-Seven

by Anthony Hecht

The harbingers are come. See, see their mark;

White is their colour; and behold my head.

—George Herbert

Long gone the smoke-and-pepper childhood smell

Of the smoldering immolation of the year,

Leaf-strewn in scattered grandeur where it fell,

Golden and poxed with frost, tarnished and sere.

And I myself have whitened in the weathers

Of heaped-up Januaries as they bequeath

The annual rings and wrongs that wring my withers,

Sober my thoughts, and undermine my teeth.

The dramatis personae of our lives

Dwindle and wizen; familiar boyhood shames,

The tribulations one somehow survives,

Rise smokily from propitiatory flames

Of our forgetfulness until we find

It becomes strangely easy to forgive

Even ourselves with this clouding of the mind,

This cinerous blur and smudge in which we live.

A turn, a glide, a quarter turn and bow,

The stately dance advances; these are airs

Bone-deep and numbing as I should know by now,

Diminishing the cast, like musical chairs.

Hecht's poem makes aging seem like sitting in a foxhole, waiting for the

inevitable end, but with the somewhat hopeful note that "it becomes strangely easy to forgive

/ even ourselves with this clouding of the mind, / this cinerous blur and smudge in which we live."

Should we thank God, perhaps, for small favors, like eroding memories?

Song For The Last Act

by Louise Bogan

Now that I have your face by heart, I look

Less at its features than its darkening frame

Where quince and melon, yellow as young flame,

Lie with quilled dahlias and the shepherd's crook.

Beyond, a garden. There, in insolent ease

The lead and marble figures watch the show

Of yet another summer loath to go

Although the scythes hang in the apple trees.

Now that I have your face by heart, I look.

Now that I have your voice by heart, I read

In the black chords upon a dulling page

Music that is not meant for music's cage,

Whose emblems mix with words that shake and bleed.

The staves are shuttled over with a stark

Unprinted silence. In a double dream

I must spell out the storm, the running stream.

The beat's too swift. The notes shift in the dark.

Now that I have your voice by heart, I read.

Now that I have your heart by heart, I see

The wharves with their great ships and architraves;

The rigging and the cargo and the slaves

On a strange beach under a broken sky.

O not departure, but a voyage done!

The bales stand on the stone; the anchor weeps

Its red rust downward, and the long vine creeps

Beside the salt herb, in the lengthening sun.

Now that I have your heart by heart, I see.

Louise Bogan is a major poet, in my opinion. Hopefully the rest of the reading

world will soon catch on. Please be sure to read her other poems on this page,

especially "After the Persian."

Epitaph for a Palestinian Child

by

Michael R. Burch

I lived as best I could, and then I died.

Be careful where you step: the grave is wide.

I suppose I shouldn't publish my own poems on such an auspicious page, but what

the hell: I think this one deserves to be read and considered.

The Snow Man

by Wallace Stevens

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Wallace Stevens called the poet the "priest of the invisible." In this poem and

in certain other poems of his, he seems to be the "priest of the nonexistent"

who takes "negative capability" to new heights (or would it be depths?). But his

best poems are wonders, whether or not one agrees with their conclusions, or understands

them.

Du

by Janet Kenny

A wisp of old woman,

curved like a scythe,

tottered to me as she

fussed her shopping,

her walking stick hooked

on her chopstick wrist.

She spoke to me then

in a dried leaf voice.

Inaudible there

in that busy street,

swept by rude gales

from passing trucks.

I leaned closer to hear:

Mein eyes not gut.

time for bus, ven comes it?

“Which bus do you want?”

She smiled, shook her head

then sang to herself

—and somebody else,

in—not German. Yiddish?

“Which bus?”

She leaned towards me,

her tiny claw reached

to stroke my face.

Du she said.

Du

This is a wonderful bit of storytelling by a contemporary poet. "Du" is the

more intimate German word for "you," so the elderly woman seems to be greeting

the poet more like a long-lost friend or family member than as a stranger.

Say, Shantih

by

Philip Quinlan

for Paul Christian Stevens

These latitudes are falsified;

wrecked deadening has done for us.

We compass the meridian,

but who will stop the sun for us?

Our sextant-blinded eyes bleed brine;

no times or tides still stay for us.

All sheets, all shrouds are cut and dried;

our cleats cannot belay for us.

In sympathy at distances:

we navigate by hunger, thirst.

Noon shadows say our will be last.

Shall stern or bow go under first?

We cross the line with rituals:

traversal which will be reversed.

We’ll Easter home at empty sail,

our mark be missed. We fare the worst.

Good Friday, 2013

This is a remarkable elegy by Philip Quinlan to his friend and fellow poet

Paul Christian Stevens.

To Earthward

by Robert Frost

Love at the lips was touch

As sweet as I could bear;

And once that seemed too much;

I lived on air

That crossed me from sweet things,

The flow of – was it musk

From hidden grapevine springs

Downhill at dusk?

I had the swirl and ache

From sprays of honeysuckle

That when they’re gathered shake

Dew on the knuckle.

I craved strong sweets, but those

Seemed strong when I was young:

The petal of the rose

It was that stung.

Now no joy but lacks salt,

That is not dashed with pain

And weariness and fault;

I crave the stain

Of tears, the aftermark

Of almost too much love,

The sweet of bitter bark

And burning clove.

When stiff and sore and scarred

I take away my hand

From leaning on it hard

In grass or sand,

The hurt is not enough:

I long for weight and strength

To feel the earth as rough

To all my length.

Robert Frost was far more than just a pragmatic New England farmer-turned-poet. "To

Earthward" is one of the best bittersweet love poems in the English language.

Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

In this stunning poem Dylan Thomas disproves nearly all the conventional

"wisdom" of the workshops: always avoid adjectives or only use esoteric ones, avoid

"predictable rhyme," don't repeat words in close proximity, etc. Thomas was yet

another great Romantic poet who died young; he may have been the best of them.

Vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat inchohare longam

by Ernest Dowson

"The brevity of life forbids us to entertain hopes of long duration" —Horace

They are not long, the weeping and the laughter,

Love and desire and hate:

I think they have no portion in us after

We pass the gate.

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for a while, then closes

Within a dream.

Dowson died at age 32 and is only known for a few poems today, but his best

poems are highly memorable. He's one of my favorite lesser-known poets.

A Last Word

by Ernest Dowson

Let us go hence: the night is now at hand;

The day is overworn, the birds all flown;

And we have reaped the crops the gods have sown;

Despair and death; deep darkness o'er the land,

Broods like an owl; we cannot understand

Laughter or tears, for we have only known

Surpassing vanity: vain things alone

Have driven our perverse and aimless band.

Let us go hence, somewhither strange and cold,

To Hollow Lands where just men and unjust

Find end of labour, where's rest for the old,

Freedom to all from love and fear and lust.

Twine our torn hands! O pray the earth enfold

Our life-sick hearts and turn them into dust.

Dowson's influence on the language and other writers can be seen in phrases like

"gone with the wind" and "the days of wine and roses." His work certainly influenced T. S.

Eliot, who once said that certain lines of Dowson "have always run in my head."

The Skeleton's Defense of Carnality

by Jack Foley

Truly I have lost weight, I have lost weight,

grown lean in love’s defense,

in love’s defense grown grave.

It was concupiscence that brought me to the state:

all bone and a bit of skin

to keep the bone within.

Flesh is no heavy burden for one possessed of little

and accustomed to its loss.

I lean to love, which leaves me lean, till lean turn into lack.

A wanton bone, I sing my song

and travel where the bone is blown

and extricate true love from lust

as any man of wisdom must.

Then wherefore should I rage

against this pilgrimage

from gravel unto gravel?

Circuitous I travel

from love to lack / and lack to lack,

from lean to lack

and back.

I love this wicked little poem by the contemporary poet Jack Foley. The male

skeleton is missing an important "member" required for lovemaking, so "lean"

really does "turn into lack" when the "bone is blown."

After the Rain

by Jared Carter

After the rain, it’s time to walk the field

again, near where the river bends. Each year

I come to look for what this place will yield—

lost things still rising here.

The farmer’s plow turns over, without fail,

a crop of arrowheads, but where or why

they fall is hard to say. They seem, like hail,

dropped from an empty sky,

yet for an hour or two, after the rain

has washed away the dusty afterbirth

of their return, a few will show up plain

on the reopened earth.

Still, even these are hard to see—

at first they look like any other stone.

The trick to finding them is not to be

too sure about what’s known;

conviction’s liable to say straight off

this one’s a leaf, or that one’s merely clay,

and miss the point: after the rain, soft

furrows show one way

across the field, but what is hidden here

requires a different view—the glance of one

not looking straight ahead, who in the clear

light of the morning sun

simply keeps wandering across the rows,

letting his own perspective change.

After the rain, perhaps, something will show,

glittering and strange.

I admire this poem by the contemporary poet Jared Carter, especially its closing lines. This poem capitalizes on the

poet's capacity for wonder.

Is there any reward?

by Hillaire Belloc

Is there any reward?

I'm beginning to doubt it.

I am broken and bored,

Is there any reward

Reassure me, Good Lord,

And inform me about it.

Is there any reward?

I'm beginning to doubt it.

It seems the only possible compassionate reactions to the "good news" of

Christianity are despair and "foxhole humor." Belloc resorts to wry good humor.

VIII—from "Sunday Morning"

by Wallace Stevens

She hears, upon that water without sound,

A voice that cries, "The tomb in Palestine

Is not the porch of spirits lingering.

It is the grave of Jesus, where he lay."

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old despondency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

"Sunday Morning" is one of the greatest poems in the English canon. The final

stanza of "Sunday Morning" contrasts human faith and its revelations to nature

and its ambiguities. As the pigeons sink downward to darkness, what can we make

of the "ambiguous undulations" of their wings?

N. W.

by Robert Mezey

On a certain street there is a certain door,

Unyielding, around which rockroses rise,

Charged with the scent of a lost paradise,

Which in the evening sunlight opens no more,

Or not to me. Once, in a better light,

Dearly awaited arms would wait for me

And in the impatient fading of the day

The joy and peace of the embracing night.

No more of that. Now, a day breaks and dies,

Releasing empty hours and impure

Fantasies, and the abuse of literature,

The lawless images and artful lies,

And pointless tears, and the envy of other men.

And then the longing for oblivion.

after Borges

This is a wonderful poem about loss, by a contemporary poet.

Evening Wind

by Robert Mezey

One foot on the floor, one knee in bed,

Bent forward on both hands as if to leap

Into a heaven of silken cloud, or keep

An old appointment—tryst, one almost said—

Some promise, some entanglement that led

In broad daylight to privacy and sleep,

To dreams of love, the rapture of the deep,

Oh, everything, that must be left unsaid—

Why then does she suddenly look aside

At a white window full of empty space

And curtains swaying inward? Does she sense

In darkening air the vast indifference

That enters in and will not be denied

To breathe unseen upon her nakedness?

after an etching by Edward Hopper

Although I haven't seen the etching by Hopper, the poem is so wonderfully

descriptive it paints a picture that stands by itself.

Those Winter Sundays

by Robert Hayden

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he'd call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love's austere and lonely offices?

I believe Robert Hayden became an immortal poet with this poem. I wonder how

many children will read it and suddenly realize how much of their lives

their parents sacrificed to their upbringing.

Juan's Song

by Louise Bogan

When beauty breaks and falls asunder

I feel no grief for it, but wonder.

When love, like a frail shell, lies broken,

I keep no chip of it for token.

I never had a man for friend

Who did not know that love must end.

I never had a girl for lover

Who could discern when love was over.

What the wise doubt, the fool believes

Who is it, then, that love deceives?

This is a wonderfully honest and ironical poem about love, from a woman's

perspective. I believe Bogan may give men too much credit (most men are just as

susceptible to the myths of love as most women are), but perhaps it avails

nothing for anyone to be "wise" in matters of love.

Tea at the Palaz of Hoon

by Wallace Stevens

Not less because in purple I descended

The western day through what you called

The loneliest air, not less was I myself.

What was the ointment sprinkled on my beard?

What were the hymns that buzzed beside my ears?

What was the sea whose tide swept through me there?

Out of my mind the golden ointment rained,

And my ears made the blowing hymns they heard.

I was myself the compass of that sea:

I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw

Or heard or felt came not but from myself;

And there I found myself more truly and more strange.

This is an interesting poem because Wallace Stevens seems to have been an

atheist, and yet he wrote one of the most mystical poems in the English

language.

Word Made Flesh

by Ann Drysdale

On the broad steps of the Basilica

The feckless hopefully hold out their hands,

Often with some success; the privileged

Lighten their consciences by a few pence

On their way to receive the sacrament.

On the seventeenth step two beggars sit

Paying no regard to the worshippers

Who file past on their way to salvation.

They do not ask for alms. They are engrossed,

Skillfully masturbating one another.

Most who have noticed this pretend they haven’t;

Some of the other beggars wish they wouldn’t.

Poor relief is incumbent on the rich

And by taking things into their own hands

They spoil the scene for everybody else.

Our Lord said, “silver and gold have I none

But such as I have give I thee”. The words

Are here made flesh; with beatific sigh

One gives the other benison, slipping

All that he has into the waiting hand

Of somebody who shares his human need.

The newly shriven filter down the steps

Averting their eyes from the seventeenth,

Where the first beggar, in a state of grace,

Works selflessly towards the second coming.

I absolutely love Ann Drysdale's poem. If only there was a God whose grace

extended to beggars masturbating each other on the steps of a

Basilica! But then what use would there be for the hellfire-and-brimstone

condemners of humankind?

in Just-

by e. e. cummings

in Just-

spring when the

world is mud-

luscious the little

lame baloonman

whistles far and wee

and eddieandbill come

running from marbles and

piracies and it's

spring

when the world is puddle-wonderful

the queer

old baloonman whistles

far and wee

and bettyandisbel come dancing

from hop-scotch and jump-rope and

it's

spring

and

the

goat-footed

baloonMan whistles

far

and

wee

This wonderfully whimsical poem juxtaposes innocent children with an equally

innocent Pan-nish balloon-man (the Devil?). Was e. e. cummings a closet

universalist, or was he perhaps making points about the innocence of children

and the machinations of the men who ogle and prey on them? I, for one, prefer

the "sweeter" interpretation.

Acquainted With The Night

by Robert Frost

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain—and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain.

I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet

When far away an interrupted cry

Came over houses from another street,

But not to call me back or say good-by;

And further still at an unearthly height,

One luminary clock against the sky

Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

This is a deliciously scary poem about human alienation. It seems we can be not

only alienated from each other, but even from ourselves. Madness ran in Frost's

family, along with a dark Calvinism. Ah, the sweet joys of fundamentalism!

Dover Beach

by Matthew Arnold

The sea is calm to-night,

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The sea of faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

This may be the first truly great modern poem, along with "The Love Song of J.

Alfred Prufrock" by T. S. Eliot. Matthew Arnold stopped writing poetry when he

could no longer "create joy," but this magnificent poem will

undoubtedly remain a joy forever.

In My Craft Or Sullen Art

by Dylan Thomas

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

I believe this poem is a wonderful validation of the art and craft of the

Romantic Poet, who writes for the sake of love, even if lovers misapprehend or

ignore him.

The Garden

by Ezra Pound

Like a skein of loose silk blown against a wall

She walks by the railing of a path in Kensington Gardens,

And she is dying piece-meal

of a sort of emotional anemia.

And round about there is a rabble

Of the filthy, sturdy, unkillable infants of the very poor.

They shall inherit the earth.

In her is the end of breeding.

Her boredom is exquisite and excessive.

She would like some one to speak to her,

And is almost afraid that I

will commit that indiscretion.

This poem is a wonderful bit of commentary on the utter strangeness of human

societies and their castes. How many of us long for companionship, but are

reluctant to seek it below our station? Is it worse to be alone, or to associate

with our "inferiors"?

Luke Havergal

by Edward Arlington Robinson

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal,

There where the vines cling crimson on the wall,

And in the twilight wait for what will come.

The leaves will whisper there of her, and some,

Like flying words, will strike you as they fall;

But go, and if you listen, she will call.

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal—

Luke Havergal.

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies

To rift the fiery night that's in your eyes;

But there, where western glooms are gathering

The dark will end the dark, if anything:

God slays Himself with every leaf that flies,

And hell is more than half of paradise.

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies—

In eastern skies.

Out of a grave I come to tell you this,

Out of a grave I come to quench the kiss

That flames upon your forehead with a glow

That blinds you to the way that you must go.

Yes, there is yet one way to where she is,

Bitter, but one that faith may never miss.

Out of a grave I come to tell you this—

To tell you this.

There is the western gate, Luke Havergal,

There are the crimson leaves upon the wall,

Go, for the winds are tearing them away,—

Nor think to riddle the dead words they say,

Nor any more to feel them as they fall;

But go, and if you trust her she will call.

There is the western gate, Luke Havergal—

Luke Havergal.

"Luke Havergal" is like a ghost story in which the reader becomes one with the

ghost. When we recognize our affinity with the poem's protagonist, the poem

becomes all the more terrifying.

I ― Easter Hymn

by A. E. Housman

If in that Syrian garden, ages slain,

You sleep, and know not you are dead in vain,

Nor even in dreams behold how dark and bright

Ascends in smoke and fire by day and night

The hate you died to quench and could but fan,

Sleep well and see no morning, son of man.

But if, the grave rent and the stone rolled by,

At the right hand of majesty on high

You sit, and sitting so remember yet

Your tears, your agony and bloody sweat,

Your cross and passion and the life you gave,

Bow hither out of heaven and see and save.

Housman is among the most direct and plainspoken of poets, and therefore among the

very strongest. He is also one of our best critics of human societies and

religion, along with Blake, Wilde, Whitman and a few others. Housman didn't

create art for art's sake, but art for humanity's sake.

The Darkling Thrush

by Thomas Hardy

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter's dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land's sharp features seemed to be

The Century's corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

If I remember things correctly, this poem was written at the close of the

nineteenth century, perhaps to usher in the twentieth. If so, at least

it closes on a somewhat hopeful note. Perhaps there is a Hope of which humanity

is unaware, and which Religion (hopefully) misapprehends.

When You Are Old

by William Butler Yeats

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

This is a near-perfect loose translation of a poem by the French poet Ronsard.

Yeats no doubt wrote it with the love of his life, Maude Gonne, in mind.

An Irish Airman Foresees His Death

by William Butler Yeats

I know that I shall meet my fate

Somewhere among the clouds above;

Those that I fight I do not hate,

Those that I guard I do not love;

My country is Kiltartan Cross,

My countrymen Kiltartan's poor,

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law, nor duty bade me fight,

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds,

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balanced all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.

Yeats wrote this poem for Robert Gregory, the son of his patron, Lady Gregory.

To understand the pilot's dilemma, we have to understand that many Irishmen had

no more love for their English conquerors than for their would-be German

conquerors.

Leda and the Swan

by William Butler Yeats

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

This is a tremendous poem about the ambiguities of love and religion, from a

woman's perspective, as related by a male poet. The madness of rape and war

combine in the "broken wall" of Troy and the broken hymen of Leda, who was raped

by the Father-God, Zeus.

the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls

by e. e. cummings

the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls

are unbeautiful and have comfortable minds

(also, with the church's protestant blessings

daughters, unscented shapeless spirited)

they believe in Christ and Longfellow, both dead,

are invariably interested in so many things—

at the present writing one still finds

delighted fingers knitting for the is it Poles?

perhaps. While permanent faces coyly bandy

scandal of Mrs. N and Professor D

.... the Cambridge ladies do not care, above

Cambridge if sometimes in its box of

sky lavender and cornerless, the

moon rattles like a fragment of angry candy

This poem by e. e. cummings makes a number of interesting points about the role

of religion in American society. Does Christianity result in "comfortable minds"

able to simultaneously undertake small acts of charity, coyly bandy gossip, and

ignore the reality of a universe which is obviously not controlled by a loving,

compassionate, benevolent "God"?

The Convergence Of The Twain

by Thomas Hardy

Lines on the loss of the "Titanic"

In a solitude of the sea

Deep from human vanity,

And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she.

Steel chambers, late the pyres

Of her salamandrine fires,

Cold currents thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres.

Over the mirrors meant

To glass the opulent

The sea-worm crawls—grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent.

Jewels in joy designed

To ravish the sensuous mind

Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind.

Dim moon-eyed fishes near

Gaze at the gilded gear

And query: "What does this vaingloriousness down here?"...

Well: while was fashioning

This creature of cleaving wing,

The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything

Prepared a sinister mate

For her—so gaily great—

A Shape of Ice, for the time far and dissociate.

And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace, and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

Alien they seemed to be;

No mortal eye could see

The intimate welding of their later history,

Or sign that they were bent

By paths coincident

On being anon twin halves of one august event,

Till the Spinner of the Years

Said "Now!" And each one hears,

And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres.

This is a near-perfect poem by one of the first modern masters. Hardy didn't

seem to believe in a benevolent God, but in some sort of inexorable process of Fate.

The Listeners

by Walter De La Mare

'Is there anybody there?' said the Traveller,

Knocking on the moonlit door;

And his horse in the silence champed the grasses

Of the forest's ferny floor:

And a bird flew up out of the turret,

Above the Traveller's head

And he smote upon the door again a second time;

'Is there anybody there?' he said.

But no one descended to the Traveller;

No head from the leaf-fringed sill

Leaned over and looked into his grey eyes,

Where he stood perplexed and still.

But only a host of phantom listeners

That dwelt in the lone house then

Stood listening in the quiet of the moonlight

To that voice from the world of men:

Stood thronging the faint moonbeams on the dark stair,

That goes down to the empty hall,

Hearkening in an air stirred and shaken

By the lonely Traveller's call.

And he felt in his heart their strangeness,

Their stillness answering his cry,

While his horse moved, cropping the dark turf,

'Neath the starred and leafy sky;

For he suddenly smote on the door, even

Louder, and lifted his head:—

'Tell them I came, and no one answered,

That I kept my word,' he said.

Never the least stir made the listeners,

Though every word he spake

Fell echoing through the shadowiness of the still house

From the one man left awake:

Ay, they heard his foot upon the stirrup,

And the sound of iron on stone,

And how the silence surged softly backward,

When the plunging hoofs were gone.

This is one of my favorite story poems. It rivals "The Highwayman" by Alfred

Noyes as the best ghost story in English poetry.

Love Is Not All

by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Love is not all: It is not meat nor drink

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain,

Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink

and rise and sink and rise and sink again.

Love cannot fill the thickened lung with breath

Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone;

Yet many a man is making friends with death

even as I speak, for lack of love alone.

It well may be that in a difficult hour,

pinned down by need and moaning for release

or nagged by want past resolution's power,

I might be driven to sell your love for peace,

Or trade the memory of this night for food.

It may well be. I do not think I would.

Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote some damn strong poems, and should also be

recognized as one of the first female poets to write honestly (and perhaps

sometimes brag) about the power of her sexuality over men.

Advice to a Girl

by Sara Teasdale

No one worth possessing