The HyperTexts

Reclaiming the Roses of Pieria

What are the Roses of Pieria, what do they represent, and what do they have to

do with the current "state of the art" of poetry? The Roses of Pieria grew on

Mount Olympus, the abode of the nine Muses of Greek poetry, literature and art,

and they thus represent the highest flowering of art. The

Roses of Pieria were mentioned in one form or another, such as "deathless

flowers," or by association with the Pierian spring where they grew, by poets like Ovid, Sappho, Antipater of Sidon,

Petronius, Alexander Pope and Ezra Pound.

Have contemporary poets lost their way? If so, how can they reclaim the Roses

of Pieria? To arrive at possible answers, let’s go back to the source and

begin with Sappho of Lesbos ...

by Michael R. Burch

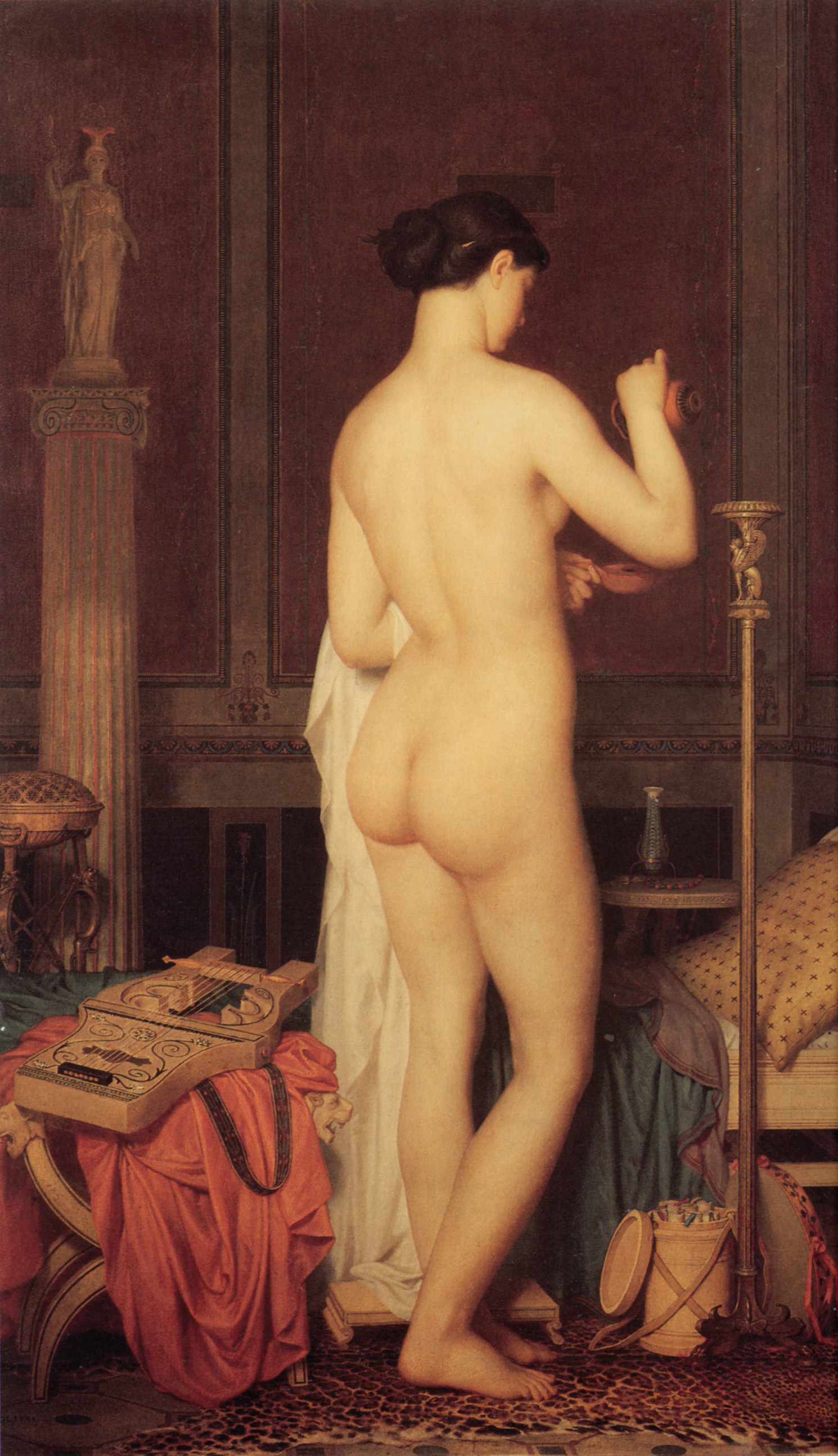

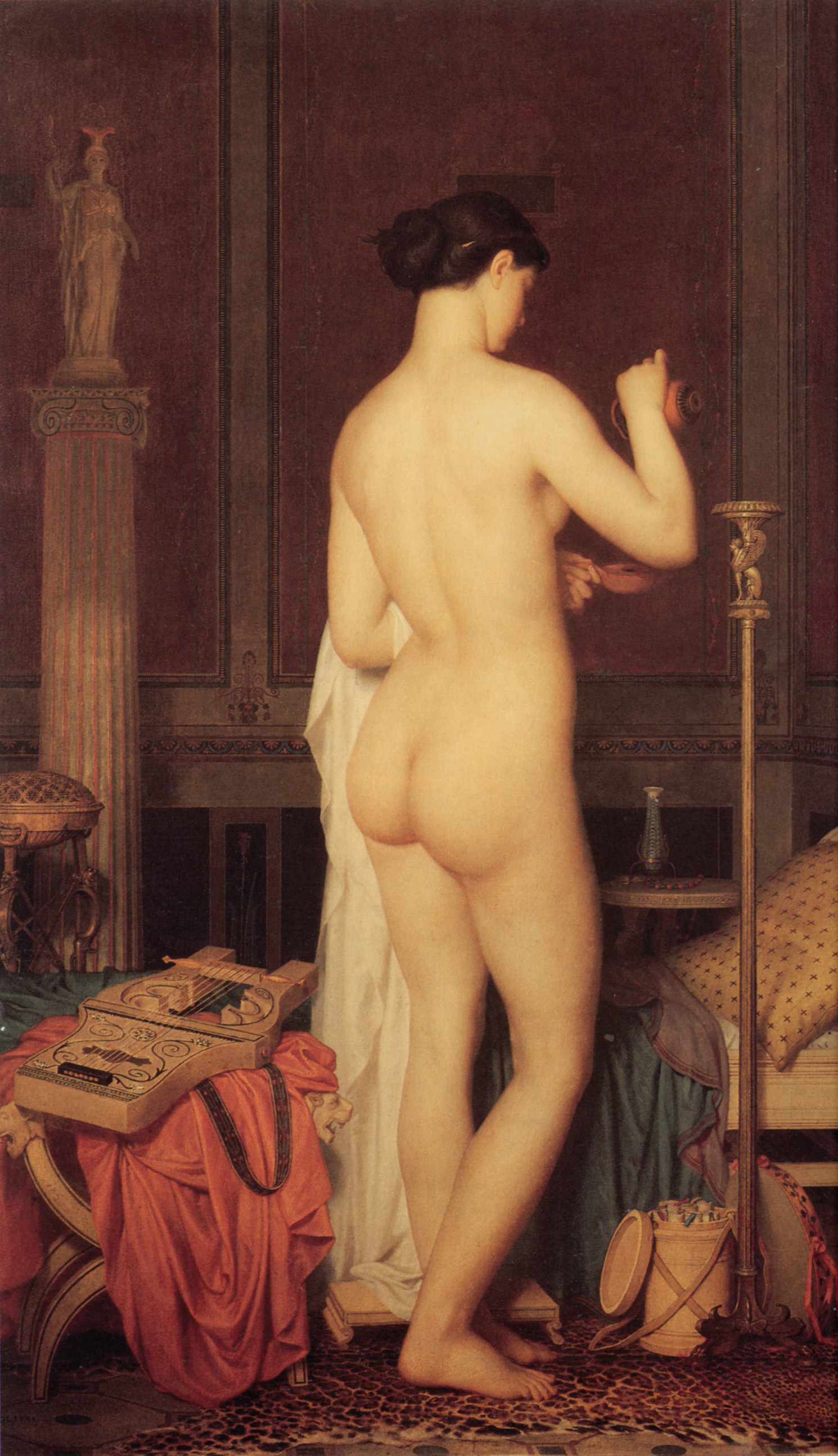

Gleyre Le Coucher de Sappho

by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre

Sappho, fragment 55

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Lady,

soon you'll lie dead, disregarded,

as your worm-eaten corpse like your corpus degrades;

for those who never gathered Pieria's roses

must mutely accept how their memory fades

as they flit

among the obscure, uncelebrated

Hadean shades.

This is my admittedly loose translation/interpretation of a Sappho

fragment, but I believe it serves my purpose here. I have provided translations

by other poets later on this page, in case your prefer theirs to mine.

This poem is, I believe, Sappho’s indictment of poets whose work does not

achieve the height of real art (i.e., poets who lack “the Roses of Pieria”). In Greek mythology

the Pierian Spring, which flowed from the northern foot of Mount Olympus, was

sacred to the Muses. The nine Muses were daughters of Zeus, goddesses, and the

inspiration of human arts and science. The Roses of Pieria grew beside the

Pierian Spring. Thus someone who lacked the Roses of Pieria lacked real artistic

inspiration.

This is another Sappho poem about roses. The rose was no ordinary flower to

Sappho, and roses planted, watered and cultivated by nine goddesses would have

been the most perfect of all.

Sappho's Rose

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

The rose is—

the ornament of the earth,

the glory of nature,

the archetype of the flowers,

the blush of the meadows,

a lightning flash of beauty.

Sappho knew she possessed the true Roses of Pieria:

Sappho, fragment 32

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

They have been very generous with me,

the violet-strewing Muses of Olympus;

thanks to their gifts

I have become famous.

Sappho may have described herself best, in her own words, as parthenon aduphonon,

"the sweet-voiced girl." If this epigram was her composition, she was fully

aware of how talented she was:

Sapphic inscription on a long-stemmed cup in an Athens museum

Mere air,

my words' fare,

but intoxicating to hear.

—loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

That epigram reminds me of William Butler Yeats, the great Irish

poet, who said of his poetry: "I made it out of a mouthful of air."

Her ancient peers agreed and were not shy about singing Sappho's praises.

According to Plutarch, Sappho's art was like "sweet-voiced songs healing love."

According to Edwin Marion Cox, a Sappho translator, the passage below was quoted

by Stobaeus and Plutarch. Another early reference is found in the Satyricon of

Petronius, circa the first century AD:

Come! Gird up thy soul! Inspiration will then force a vent

And rush in a flood from a heart that is loved by the Muse!

—Petronius, translation by W.C. Firebaugh

Antipater of Sidon mentioned "deathless flowers" in one of his tributes to Sappho:

Mnemosyne was stunned into astonishment when she heard honey-tongued Sappho,

wondering how mortal men merited a tenth Muse.

—Antipater of Sidon,

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

O ye who ever twine the three-fold thread,

Ye Fates, why number with the silent dead

That mighty songstress whose unrivalled powers

Weave for the Muse a crown of deathless flowers?

—Antipater of Sidon,

translation by Francis Hodgson

O Aeolian land, you lightly cover Sappho,

the mortal Muse who joined the Immortals,

whom Cypris and Eros fostered,

with whom Peitho wove undying wreaths,

who was the joy of Hellas and your glory.

O Fates who twine the spindle's triple thread,

why did you not spin undying life

for the singer whose deathless bouquets

enchanted the Muses of Helicon?

—Antipater of Sidon,

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Plato apparently agreed with Antipater, as did other poets many centuries later:

Some thoughtlessly proclaim the Muses nine;

A tenth is Lesbian Sappho, maid divine.

—Plato, translated by Lord Neaves

Had Sappho's self not left her word

thus long

For token,

The sea round Lesbos yet in waves of song

Had spoken.

—Charles Algernon Swinburne

When her ancient Greek peers nominated Sappho to be the Tenth Muse, they were

apparently elevating her above all other poets up to their era. By

Plato's time, the poets Sappho leapfrogged would have included Homer, Archilochus, Alcman, Alcaeus, Anacreon, Pindar, Simonides, Sophocles, Aesop,

Euripides and Aristophanes. That's pretty heady company! But who was Sappho, and

was she really that good?

Sappho was born around 630 B.C. on the island of Lesbos and lived there in the

port city of Mytilene. It is believed that she came from a wealthy family and

had three brothers, two of whom are named in her poems. It is also believed that

she was married and had a daughter named Cleïs. Sappho was apparently exiled to

Sicily around 600 B.C. and may have continued to live there until her death

around 570 B.C. Not much else is known about her, other than what can be gleaned

from her poems and from what other classical authors wrote about her. However,

Sappho's poems are mostly fragments and much of what was written about her came

long after her own day and may not be accurate. For instance, her father was

given ten different names! We do know, however, that Sappho and her poetry were

highly esteemed.

Sappho's

specialty was lyric poetry, so-called because it was either recited or sung to the

accompaniment of the lyre (a harp-like instrument). "She is a mortal marvel"

wrote

Antipater of Sidon, before proceeding to catalog the seven wonders of the

world. Plato numbered her among the wise. Plutarch said the grace of her

poems acted on audiences like an enchantment, so that when he read her poems he

set aside his drinking cup in shame. Strabo called her "something wonderful,"

saying he knew of "no woman who in any, even the least degree, could be compared to

her for poetry." Solon so loved one of her songs that he remarked, "I just

want to learn it and die." Sappho was so highly regarded that her face graced six different ancient coins. But perhaps the

greatest testimony to her talent and enduring fame is the long line of poets

who have paid homage to her over the centuries.

Sappho is known especially for her "Sapphics"―love

poems and songs―some of which are considered to be bisexual in nature, or lesbian (a term derived from the name of her island home, Lesbos).

But was Sappho just another love poet, or was she the Love Poet?

According to Margaret Reynolds: "Certainly Sappho seems to have been an original

inventor of the language of sexual desire." Unfortunately, the only completely

intact poem left by Sappho is her "Ode to Aphrodite" or "Hymn to Aphrodite" (an

interesting synchronicity since Sappho is best known as a love poet and

Aphrodite was the ancient Greek goddess of love). In any case, Sappho is

remembered today primarily for her epigrammatic "fragments" and the efforts of

her many translators to restore them. In some cases a fragment consists of just

a word or two, and the translator/interpreter must provide the rest.

Was Sappho the first great Romantic poet, two millennia before Blake, Burns,

Byron, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats? Was she the first modern poet

as well? Perhaps, because according to J. B. Hare, "Sappho had the audacity to

use the first person in poetry and to discuss deep human emotions, particularly

the erotic, in ways that had never been approached by anyone before her." Before

Sappho, poetry was primarily used for ceremonial, religious and storytelling

purposes. But Sappho used poetry to explore herself and her relationships with

others. She laid herself bare in ways that other poets would also do―given two

thousand years to catch up! Today, when we hear songwriters like Bob Dylan,

Prince, Adele and Taylor Swift baring their souls, we are surely hearing echoes

of the first great lyric poet, Sappho of Lesbos, who truly possessed the Roses

of Pieria.

Skipping forward in time, the inspirational Pierian Spring was mentioned in

Alexander Pope's 1711 poem "An Essay on Criticism" as the metaphorical source of

knowledge and understanding of art and science:

A little learning is a dang'rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fir'd at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts …

The name of the spring derives from the Pierides, the daughters of King

Pierus who sought a contest with the Muses. When they lost, they were

transformed into magpies, as related in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It was not, alas,

a happy transformation: “As they tried to speak, and made great clamour, and

with shameless hands made threatening gestures, suddenly stiff quills sprouted

from out their finger-nails, and plumes spread over their stretched arms; and

they could see the mouth of each companion growing out into a rigid beak. And

thus new birds were added to the forest. While they made complaint, these

Magpies that defile our groves, moving their stretched-out arms, began to float,

suspended in the air. And since that time their ancient eloquence, their

screaming notes, their tiresome zeal of speech have all remained.”

Let’s skip forward again, this time to 1920 and “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” by

Ezra Pound. HSM has been regarded as a turning point in Pound's career, by F.R. Leavis and others. Soon after the poem’s completion Pound left England.

Mauberley is generally considered to be self-referential, in the mould of

Pound’s protégé T. S. Eliot in his poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

At the conclusion of his poem, Pound brings up the Roses of Pieria:

Hugh Selwyn Mauberley [Part I]

by Ezra Pound

...

Conduct, on the other hand, the soul

“Which the highest cultures have nourished”

To Fleet St. where

Dr. Johnson flourished;

Beside this thoroughfare

The sale of half-hose has

Long since superseded the cultivation

Of Pierian roses.

Envoi (1919)

Go, dumb-born book,

Tell her that sang me once that song of Lawes:

Hadst thou but song

As thou hast subjects known,

Then were there cause in thee that should condone

Even my faults that heavy upon me lie

And build her glories their longevity.

Tell her that sheds

Such treasure in the air,

Recking naught else but that her graces give

Life to the moment,

I would bid them live

As roses might, in magic amber laid,

Red overwrought with orange and all made

One substance and one colour

Braving time.

Tell her that goes

With song upon her lips

But sings not out the song, nor knows

The maker of it, some other mouth,

May be as fair as hers,

Might, in new ages, gain her worshippers,

When our two dusts with Waller's shall be laid,

Siftings on siftings in oblivion,

Till change hath broken down

All things save Beauty alone.

Here “that song of Lawes” is a reference to the English composer Henry

Lawes, who set a number of the poems by the English poet Edmund Waller to music.

And it is Waller’s exquisite poem "Go, Lovely Rose" that Pound is quite

obviously riffing on in the envoy of HSM:

Song: Go, Lovely Rose

by Edmund Waller

Go, lovely rose!

Tell her that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows,

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.

Tell her that’s young,

And shuns to have her graces spied,

That hadst thou sprung

In deserts, where no men abide,

Thou must have uncommended died.

Small is the worth

Of beauty from the light retired;

Bid her come forth,

Suffer herself to be desired,

And not blush so to be admired.

Then die! that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee;

How small a part of time they share

That are so wondrous sweet and fair!

Waller was a contemporary of John Milton; they were born one year apart. A.

E. Housman expressed the opinion that there was a long “dry spell” in English

poetry between the last major poems of John Milton, who published Paradise Lost

in 1667 and Samson Agonistes in 1671, and those of the first great English

Romantic poet, William Blake, who published Songs of Innocence in 1789. That’s a

very long dry spell, if Housman is correct, of around 120 years. While there

were accomplished poets who wrote in the interim, notably John Dryden and

Alexander Pope, one might question, along with Housman, whether they possessed

the Roses of Pieria.

Who reclaimed the Roses of Pieria? In English poetry it was the great

Romantics — Blake, Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Percy Bysshe

Shelley and William Wordsworth — often called the “big six.” I would add to

their number the great Scottish poet Robert Burns, the “marvellous boy” Thomas

Chatterton, John Clare and Thomas Gray.

Which English language poets had the Roses of Pieria? For me, in addition to

the poets above, they include, chronologically, Geoffrey Chaucer, Charles

d’Orleans, William Dunbar, Thomas Wyatt, Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare,

John Donne, Ben Jonson, Robert Herrick, Edmund Waller, John Milton, Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow, Edgar Allan Poe, Alfred Tennyson, Walt Whitman, Emily

Dickinson, Christina Rossetti, Thomas Hardy, Gerard Manley Hopkins, A. E.

Housman, W. B. Yeats, Ernest Dowson, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, D. H.

Lawrence, Ezra Pound, Robinson Jeffers, T. S. Eliot, Edna St. Vincent Millay,

Wilfred Owen, e. e. cummings, Louise Bogan, Hart Crane, Langston Hughes, W. H.

Auden, Dylan Thomas, Richard Wilbur, Philip Larkin, Sylvia Plath and Seamus

Heaney. Although I didn’t plan it out, that gives me an even fifty immortals.

Where do we go from here? It’s interesting to note that only 11 of my

immortals predate the Romantics, while 29 have written since, within the last

two centuries. And 22 of the poets, or nearly half, wrote in the twentieth

century. So I suspect the “death” of poetry has been greatly exaggerated. And

who knows — perhaps poets among us are cultivating new Roses of Pieria even as I

conclude this essay. How will we know? When they knock our socks off and have us

riffing on their poems, like Pound in his envoy.

As I promised, here are other translations of the first Sappho poem I offered.

The alternate translations are followed by other Sappho poems having to do with

flowers and/or art.

Κατθάνοισα δὲ κείσεαι πότα, κωὐ μναμοσύνα σέθεν

ἔσσετ᾽ οὔτε τότ᾽ οὔτ᾽ ύ᾽στερον. οὐ γὰρ πεδέχεισ βρόδοων

τῶν ἐκ Πιερίασ ἀλλ᾽ ἀφάνησ κἠν᾽ ᾽Αῖδα δόμοισ

φοιτάσεισ πεδ᾽ ἀμαύρων νέκυων ἐκπεποταμένα.

Sappho, fragment 55 (Lobel-Page 55 / Voigt 55 / Diehl 58 / Bergk 68

/ Cox 65)

by

H. T. Wharton

But thou shalt ever lie dead,

nor shall there be any remembrance of thee then or thereafter,

for thou hast not of the roses of Pieria;

but thou shalt wander obscure even in the house of Hades,

flitting among the shadowy dead.

Sappho, fragment 55 (Lobel-Page 55 / Voigt 55 / Diehl 58 / Bergk 68

/ Cox 65)

by

Thomas Hardy

Dead shalt thou lie; and nought

Be told of thee or thought,

For thou hast plucked not of the Muses' tree:

And even in Hades' halls

Amidst thy fellow-thralls

No friendly shade thy shade shall company!

Sappho, fragment 55 (Lobel-Page 55 / Voigt 55 / Diehl 58 / Bergk 68

/ Cox 65)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

1.

Lady,

soon you'll lie dead, disregarded,

as your worm-eaten corpse like your corpus degrades;

for those who never gathered Pieria's roses

must mutely accept how their memory fades

as they flit

among the obscure, uncelebrated

Hadean shades.

2.

Lady,

soon you'll lie dead, disregarded,

as your worm-eaten corpse like your verse degrades;

for those who never gathered

Pierian roses

must mutely accept how their reputation fades

among the obscure, uncelebrated

Hadean shades.

3.

Lady,

soon you'll lie dead, disregarded;

then imagine how quickly your reputation fades ...

when

you who never gathered

the roses of Pieria

mutely assume your place

among the obscure, uncelebrated

Hadean shades.

"Quoted by Stobaeus about A.D. 500 as addressed to a woman of no education.

Plutarch also quotes this fragment, twice in fact, once as if written to a rich

woman, and again when he says that the crown of roses was assigned to the Muses,

for he remembers that Sappho had said these same words to some uneducated

woman."―Edwin Marion Cox

As J. B. Hare, one of her translators, said, "Sappho the poet was an innovator. At the time poetry was principally used in ceremonial

contexts, and to extoll the deeds of brave soldiers. Sappho had the audacity to use the first person in poetry and to discuss deep human

emotions, particularly the erotic, in ways that had never been approached by anyone before her. As for the military angle, in one of the

longer fragments (#3) she says: 'Some say that the fairest thing upon the dark earth is a host of horsemen, and some say a host of foot

soldiers, and others again a fleet of ships, but for me it is my beloved.' In the ancient world she was considered to be on an equal

footing with Homer, and was acclaimed as the 'tenth muse.'"

It is because of the homoerotic nature of certain of Sappho's poems that "Lesbian" and "Sapphic" have their current sexual denotations and

connotations. Many of her poems are about her female companions, but are suggestive rather than graphically sexual. For instance:

Sappho, fragment 3 (Lobel-Page 160 / Diehl 11 / Cox 11)

by Julia Dubnoff

Now, I shall sing these songs

Beautifully

for my companions.

"Athanaeus quotes this to show that there is not necessarily any reproach in the

word ἐταίραι. Like many others, the fragment is unfortunately too short for

anything but a literal translation. The breathing of the word in question in

Attic Greek would of course be rough."―Edwin Marion Cox

Sappho, fragment 118

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Sing, my sacred tortoiseshell lyre;

come, let my words

accompany your voice.

"Quoted by Hermogenes and Eustathius. Sappho is apparently addressing her lyre.

The legend is that Hermes is supposed to have made the first lyre by stretching

the strings across the cavity of a tortoise's shell."―Edwin

Marion Cox

NOTE: I seem to remember the term "sacred tortoiseshell lyre" appearing in

another translation of Sappho, but I have not been able to find the translation

or translator's name to give proper credit. Cox used the

term "divine shell" in his translation and mentioned the shell belonging to a

tortoise in his notes, so it seems like a reasonable interpretation.―MRB

Μνάσεσθαί τινά φαμι καὶ ὔστερον ἄμμεων

Sappho, fragment 29 (Lobel-Page 147 / Cox 30)

by J. V. Cunningham

Someone, I insist, will remember us!

Sappho, fragment 29 (Lobel-Page 147 / Cox 30)

by Edwin Marion Cox

I think men will remember us hereafter.

Sappho, fragment 147 (Lobel-Page 147 / Cox 30)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Someone, somewhere

will remember us,

I swear!

"From Dio Chrysostom, who, writing about A.D. 100, remarks that this is said

'with perfect beauty.'"―Edwin Marion Cox

Αἴθ᾽ ἔγο χρυσοστέφαν᾽ Ἀφρόδιτα, τόνδε τὸν πάλον λαχόην.

Sappho, fragment 33 (Lobel-Page 33 / Diehl 9 / Bergk 9 / Cox 9)

by Edwin Marion Cox

May I win this prize, O golden-crowned Aphrodite!

"From Apollonius. Sappho invented many beautiful epithets to apply to Aphrodite,

and this fragment contains one of them."―Edwin Marion Cox

Σὺ δὲ στεφάνοισ, α Δίκα περθέσαθ᾽ ἐράταισ φόβαισιν, ὄρπακασ ἀνήτοιο συν

ῤραισ᾽ ἀπάλαισι χέψιν, ἐγάνθεσιν ἔκ γὰρ πέλεται καὶ χάριτοσ μακαιρᾶν μᾶλλον

προτέρην, ἀστερφανώτοισι δ᾽ ἀπυστερέφονται.

Sappho, fragment 82 (Lobel-Page 82 / 80D / Cox 75)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Dica! Do not enter the presence of Goddesses ungarlanded!

First weave sprigs of dill with those delicate hands, if you desire their favor!

Sappho, fragment 75 (Lobel-Page 82 / 80D / Cox 75)

by Edwin Marion Cox

Do thou, O Dica, set garlands upon thy lovely hair,

weaving sprigs of dill with thy delicate hands;

for those who wear fair blossoms may surely stand first,

even in the presence of Goddesses who look without

favour upon those who come ungarlanded.

"Athenaeus quotes this fragment, saying that according to Sappho those who

approach the gods should wear garlands, as beautiful things are acceptable to

them."―Edwin

Marion Cox

Ἕγω δὲ φίλημ᾽ ἀβροσύναν, καὶ μοι τὸ λάμπρον

ἔροσ ἀελίω καὶ τὸ κάλον λέλογχεν.

Sappho, fragment 76 (Lobel-Page 58.25-26 / Cox 76)

by H. T. Wharton

I love delicacy, and for me Love has the sun's splendour and beauty.

Sappho, fragment 76 (Lobel-Page 58.25-26 / Cox 76)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

1.

I cherish extravagance,

intoxicated by Love's celestial splendor.

2.

I love the sensual

as I love the sun's ecstatic brilliance.

3.

I love the sensual

as I love the sun's splendor.

From Athenaeus, according to Edwin Marion Cox.

A Hymn to Venus

from the Greek of Sappho

Ambrose Philips

O Venus, beauty of the skies,

To whom a thousand temples rise,

Gaily false in gentle smiles,

Full of love-perplexing wiles;

O goddess, from my heart remove

The wasting cares and pains of love.

If ever thou hast kindly heard

A song in soft distress preferred,

Propitious to my tuneful vow,

O gentle goddess, hear me now.

Descend, thou bright immortal guest,

In all thy radiant charms confessed.

Thou once didst leave almighty Jove

And all the golden roofs above;

The car thy wanton sparrows drew,

Hovering in air they lightly flew;

As to my bower they winged their way

I saw their quivering pinions play.

The birds dismissed (while you remain)

Bore back their empty car again:

Then you, with looks divinely mild,

In every heavenly feature smiled,

And asked what new complaints I made,

And why I called you to my aid?

What frenzy in my bosom raged,

And by what cure to be assuaged?

What gentle youth I would allure,

Whom in my artful toils secure?

Who does thy tender heart subdue,

Tell me, my Sappho, tell me who?

Though now he shuns thy longing arms,

He soon shall court thy slighted charms;

Though now thy offerings he despise,

He soon to thee shall sacrifice;

Though now he freeze, he soon shall burn,

And be thy victim in his turn.

Celestial visitant, once more

Thy needful presence I implore.

In pity come, and ease my grief,

Bring my distempered soul relief,

Favour thy suppliant's hidden fires,

And give me all my heart desires.

Hymn to Aphrodite (Lobel-Page 1)

by Sappho

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Immortal Aphrodite, throned in splendor!

Wile-weaving daughter of Zeus, enchantress and beguiler!

I implore you, dread mistress, discipline me no longer

with such vigor!

But come to me once again in kindness,

heeding my prayers, as you did so graciously before;

O, come Divine One, descend once more

from heaven's

golden dominions!

Then with your chariot yoked to love's

white consecrated doves,

their multitudinous pinions aflutter,

you came gliding from heaven's shining heights,

to this dark gutter.

Swiftly they came and vanished, leaving you,

O my Goddess, smiling, your face eternally beautiful,

asking me what unfathomable longing

compelled me

to cry out.

Asking me what I sought in my bewildered desire.

Asking, "Who has harmed you,

why are you so alarmed,

my poor Sappho?

Whom should Persuasion

summon here?"

"Although today she flees love, soon she will pursue you;

spurning love's gifts, soon she shall give them;

tomorrow she will woo you,

however unwillingly!"

Come to me now, O most Holy Aphrodite!

Free me now from my heavy heartache and anguish!

Graciously grant me all I request!

Be once again my

ally and protector!

"Hymn to Aphrodite" is the only poem by Sappho of Lesbos to survive in its

entirety. The poem survived intact because it was quoted in full by Dionysus, a

Roman orator, in his "On Literary Composition," published around 30 B.C.

A number of Sappho's poems mention or are addressed to Aphrodite, the Greek

goddess of love. It is believed that Sappho may have belonged to a cult that

worshiped Aphrodite with songs and poetry. If so, "Hymn to Aphrodite" may have

been composed for performance within the cult. However, we have few verifiable

details about the "real" Sappho, and much conjecture based on fragments of her

poetry and what other people said about her, in many cases centuries after her

death. We do know, however, that she was held in very high regard. For instance,

when Sappho visited Syracuse the residents were so honored they erected a statue

to commemorate the occasion! During Sappho's lifetime, coins of Lesbos were

minted with her image. Furthermore, Sappho was called "the Tenth Muse" and the

other nine were goddesses. Here is another translation of the same poem ...

Hymn to Aphrodite

by Sappho

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Rainbow-appareled, immortal-throned Aphrodite,

daughter of Zeus, wile-weaver, I beseech you: Hail!

Spare me your reproaches and chastisements.

Do not punish, dire Lady, my penitent soul!

But come now, descend, favor me with your presence.

Please hear my voice now beseeching, however unclear or afar,

your own dear voice, which is Olympus’s essence —

golden, wherever you are ...

Begging you to harness your sun-chariot’s chargers —

those swift doves now winging you above the black earth,

till their white pinions whirring bring you down to me from heaven

through earth’s middle air ...

Suddenly they arrived, and you, O my Blessed One,

smiling with your immortal countenance,

asked what hurt me, and for what reason

I cried out ...

And what did I want to happen most

in my crazed heart? "Whom then shall Persuasion

bring to you, my dearest? Who,

Sappho, hurts you?”

“For if she flees, soon will she follow;

and if she does not accept gifts, soon she will give them;

and if she does not love, soon she will love

despite herself!"

Come to me now, relieve my harsh worries,

free me heart from its anguish,

and once again be

my battle-ally!

Sappho, fragment 2 (Lobel-Page 2 / Voigt 2 / Diehl 5, 6 / Bergk 4,

5)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Come, Cypris, from Crete

to meet me at this holy temple

where a lovely grove of apples awaits our presence

bowering altars

fuming with frankincense.

Here brisk waters babble beneath apple branches,

the grounds are overshadowed by roses,

and through the flickering leaves

enchantments shimmer.

Here the horses will nibble flowers

as we gorge on apples

and the breezes blow

honey-sweet with nectar ...

Here, Cypris, we will gather up garlands,

pour the nectar gracefully into golden cups

and with gladness

commence our festivities.

Sappho, fragments 54, 94 & 16

by F. T. Palgrave

Sappho loves flowers with a

personal sympathy.

"Cretan girls," she says, "with their soft feet dancing

lay flat the tender bloom of the grass."

She feels for the hyacinth

"which shepherds on the mountain tread under foot,

and the purple flower is on the ground."

She pities the wood-doves

as their "life grows cold and their wings fall"

before the archer.

Sappho, fragment 146

by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Song of the Rose

If Zeus chose us a king of the flowers in his mirth,

He would call to the Rose and would royally crown it,

For the Rose, ho, the Rose, is the grace of the earth,

Is the light of the plants that are growing upon it.

For the Rose, ho, the Rose, is the eye of the flowers,

Is the blush of the meadows that feel themselves fair—

Is the lightning of beauty that strikes through the

bowers

On pale lovers who sit in the glow unaware.

Ho, the Rose breathes of love! Ho, the Rose lifts the

cup

To the red lips of Cypris invoked for a guest!

Ho, the Rose, having curled its sweet leaves for the

world,

Takes delight in the motion its petals keep up,

As they laugh to the wind as it laughs from the west!

αμφὶ δ᾽ ὔδωρ

ψῖχρον ὤνεμοσ κελάδει δἰ ὔσδων

μαλίνων, αἰθυσσομένων δὲ φύλλων

κῶμα κατάρρει.

Sappho, fragments 93 & 94 (Lobel-Page 105a / Voigt 105a / Diehl 116

/ Bergk 93 / Cox 90)

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Beauty

I.

Like the sweet apple which reddens upon the topmost

bough,

A-top on the topmost twig,—which the pluckers forgot, somehow,—

Forgot it not, nay, but got it not, for none could get

it till now.

II.

Like the wild hyacinth flower which on the hills is

found,

Which the passing feet of the shepherds for ever tear

and wound,

Until the purple blossom is trodden into the ground.

Sappho, fragment 93 (Lobel-Page 105a / Voigt 105a / Diehl 116 /

Bergk 93 / Cox 90)

by Stanley Lombardo

Like the sweet apple reddening on the topmost branch,

the topmost apple on the tip of the branch,

and the pickers forgot it,

well, no, they didn’t forget, they just couldn’t reach it.

Sappho, fragment 105 (Lobel-Page 105a / Voigt 105a / Diehl 116 /

Bergk 93 / Cox 90)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

You're the sweetest apple reddening on the highest bough,

which the harvesters missed, or forgot—somehow—

or perhaps they just couldn't reach you—then or now.

"Quoted by the Scholiast on Hermogenes and elsewhere. The 'sweetapple' to which

Sappho refers was probably the result of a a graft of apple on quince."―Edwin Marion Cox

Sappho, fragment 132 (Lobel-Page 132)

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

1.

I have a delightful daughter

fairer than the fairest flowers, Cleis,

whom I cherish more than all Lydia and lovely Lesbos.

2.

I have a lovely daughter

with a face like the fairest flowers,

my beloved Cleis …

It bears noting that Sappho mentions her daughter and brothers, but not her

husband. We do not know if this means she was unmarried, because so many of her

verses have been lost.

The following are links to other translations by Michael R. Burch:

Ancient Greek Epigrams and Epitaphs

Poems about EROS and CUPID

The Roses of Pieria

Antipater of Sidon

Meleager

Sappho

The Longer Poems of Sappho of Lesbos

The Seafarer

Wulf and Eadwacer

The Love Song of Shu-Sin: The Earth's Oldest Love Poem?

Sweet Rose of Virtue

How Long the Night

Caedmon's Hymn

Anglo-Saxon Riddles and Kennings

Bede's Death Song

The Wife's Lament

Deor's Lament

Lament for the Makaris

Tegner's Drapa

Alexander Pushkin's tender, touching poem "I

Love You" has been translated into English by Michael R. Burch.

Whoso List to Hunt

Basho

Oriental Masters/Haiku

Miklós Radnóti

Rainer Maria Rilke

Marina Tsvetaeva

Renée Vivien

Ono no Komachi

Allama Iqbal

Bertolt Brecht

Ber Horvitz

Paul Celan

Primo Levi

Ahmad Faraz

Sandor Marai

Wladyslaw Szlengel

Saul Tchernichovsky

Robert Burns: Original Poems and Translations

The Seventh Romantic: Robert Burns

Free Love Poems by Michael R. Burch

The HyperTexts