The HyperTexts

Holocaust Poems for Students and Teachers

This Holocaust poetry page has been created for students, scholars, teachers and

educators. Its purpose is to present poems about the Holocaust and give

background information about the poets and the horrifying circumstances under which their

poems were written. The Hebrew word for the Holocaust is Shoah ("Catastrophe");

thus poems written by Jewish Holocaust poets may also be called Shoah poetry. We

have also published Holocaust writings by Germans who opposed the Nazis, a

Romani Gypsy, an Estonian, even Pope John Paul II. You can also find an extensive

index of writings by victims and survivors of the Holocaust below, along with

poems that oppose racism, intolerance, war, genocide and ethnic cleansing. The

poems and essays that follow include the Holocaust-related writings of

Miklós Radnóti, Martin Niemöller,

the schoolboy poet Franta Bass,

Bertolt Brecht,

Paul Celan,

Anita Dorn,

Primo Levi,

Chaya Feldman, Anthony Hecht,

Ber Horvitz, Mary Elizabeth Frye, Carl Sandburg,

Albert Einstein,

Elie Wiesel, Czeslaw Milosz,

Margaret

Atwood,

Janusz Korczak,

Jerzy Ficowski,

Yala Korwin, Samuel Menashe,

Chaim Nachman Bialik,

Wladyslaw Szlengel

and

Bronislawa Wajs.

intro by Michael R. Burch, editor, The HyperTexts

On Auschwitz now the reddening sunset settles;

they sleep alike—diminutive and tall,

the innocent, the "surgeons."

Sleeping, all ...

The poem "Auschwitz Rose" is dedicated to all

victims and survivors of the Holocaust. To read the full poem, please click the picture above. In Mary Rae's painting, the Rose is thornless,

representing women and children who are defenseless unless we choose to protect them. As we read the Witnesses who follow, let's all

say "Never again!" and pledge to protect all women and all children from all such atrocities.

The most famous Holocaust poem of all time, "First They Came for the Jews," was written by Martin Niemöller, a Lutheran pastor and

theologian who was born in Germany in 1892. At one time a supporter of Hitler’s policies, he eventually

recanted and as a result

was arrested and confined to the Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps from 1938 to 1945. After narrowly avoiding execution at the

hands of the Nazis, he was liberated by the Allies in 1945 and continued his career in Germany as a clergyman, pacifist and anti-war activist.

First They Came For The Jews

by Martin Niemöller

First they came for the Jews

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for the Communists

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the trade unionists

and I did not speak out

because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for me

and there was no one left

to speak out for me.

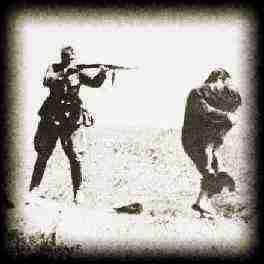

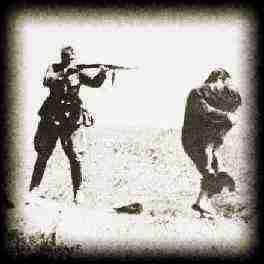

Franta Bass: The Little Boy With His Hands Up

Frantisek “Franta” Bass was a Jewish boy born in Brno, Czechoslovakia in 1930. When he was just eleven years old, his family was deported by the Nazis to Terezin, where the SS had created a hybrid Ghetto/Concentration

Camp just north of Prague (it was also known as Theresienstadt). Franta Bass was one of many little boys and girls who lived there under terrible conditions for three years. He was then sent to Auschwitz, where on October

28th, 1944, he was murdered at age fourteen. While no one knows the real

identity of the little boy with his hands up in the picture above, we can easily

imagine the Jewish schoolboy poet Franta Bass to be him, writing his touching

poems despite the cruelty and brutality he faced at the hands of sadistic

racists. We pray that no one we know ever undergoes such horrors again. If

you are a student doing a school paper or report on the Holocaust, we think

Franta Bass is a good subject for your paper, and we have provided his two

surviving poems below ...

The Garden

by Franta Bass

translation by Michael R. Burch

A small garden,

so fragrant and full of roses!

The path the little boy takes

is guarded by thorns.

A small boy, a sweet boy,

growing like those budding blossoms!

But when the blossoms have bloomed,

the boy will be no more.

Jewish Forever

by Franta Bass

translation by Michael R. Burch

I am a Jew and always will be, forever!

Even if I should starve,

I will never submit!

But I will always fight for my people,

with my honor,

to their credit!

And I will never be ashamed of them;

this is my vow.

I am so very proud of my people now!

How dignified they are, in their grief!

And though I may die, oppressed,

still I will always return to life ...

Miklós Radnóti [1909-1944], a Hungarian Jew and a fierce anti-fascist, is perhaps the greatest of the Holocaust poets. He was born in Budapest

in 1909. In 1930, at the age of 21, he published his first collection of poems, Pogány köszönto (Pagan Salute). His next book, Újmódi

pásztorok éneke (Modern Shepherd's Song) was confiscated on grounds of "indecency," earning him a light jail sentence. In 1931 he spent two

months in Paris, where he visited the "Exposition coloniale" and began translating African poems and folk tales into Hungarian. In

1934 he obtained his Ph.D. in Hungarian literature. The following year he married Fanni (Fifi) Gyarmati; they settled in Budapest. His book

Járkálj csa, halálraítélt! (Walk On, Condemned!) won the prestigious Baumgarten Prize in 1937. Also in 1937 he wrote his Cartes

Postales (Postcards from France), which were precurors to his darker images of war, Razglednicas (Picture Postcards). During World

War II, Radnóti published translations of Virgil, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Eluard, Apollinare and Blaise Cendras in Orpheus nyomában. From

1940 on, he was forced to serve on forced labor battalions, at times arming and disarming explosives on the Ukrainian front. In 1944 he was

deported to a compulsory labor camp near Bor, Yugoslavia. As the Nazis retreated from the approaching Russian army, the Bor concentration

camp was evacuated and its internees were led on a forced march through Yugoslavia and Hungary. During what became his death march, Radnóti

recorded poetic images of what he saw and experienced. After writing his fourth and final "Postcard," Radnóti was badly beaten by a soldier

annoyed by his scribblings. Soon thereafter, the weakened poet was shot to death, on November 9, 1944, along with 21 other prisoners who unable

to walk. Their mass grave was exhumed after the war and Radnóti's poems were found on his body by his wife, inscribed in pencil in a small

Serbian exercise book. Radnóti's posthumous collection, Tajtékos ég (Clouded Sky, or Foaming Sky) contains odes to his wife, letters,

poetic fragments and his final Postcards. Unlike his murderers, Miklós Radnóti never lost his humanity, and his empathy continues to live on

and shine through his work.

Postcard 1

by Miklós Radnóti

written August 30, 1944

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Out of Bulgaria, the great wild roar of the artillery thunders,

resounds on the mountain ridges, rebounds, then ebbs into silence

while here men, beasts, wagons and imagination all steadily increase;

the road whinnies and bucks, neighing; the maned sky gallops;

and you are eternally with me, love, constant amid all the chaos,

glowing within my conscience — incandescent, intense.

Somewhere within me, dear, you abide forever —

still, motionless, mute, like an angel stunned to silence by death

or a beetle hiding in the heart of a rotting tree.

Postcard 2

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 6, 1944 near Crvenka, Serbia

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

A few miles away they're incinerating

the haystacks and the houses,

while squatting here on the fringe of this pleasant meadow,

the shell-shocked peasants quietly smoke their pipes.

Now, here, stepping into this still pond, the little shepherd girl

sets the silver water a-ripple

while, leaning over to drink, her flocculent sheep

seem to swim like drifting clouds.

Postcard 3

by Miklós Radnóti

written October 24, 1944 near Mohács, Hungary

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

The oxen dribble bloody spittle;

the

men pass blood in their piss.

Our stinking regiment halts, a horde of perspiring savages,

adding our aroma to death's repulsive stench.

Postcard 4

by Miklós Radnóti

his final poem, written October 31, 1944 near Szentkirályszabadja, Hungary

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I toppled beside him — his body already taut,

tight as a string just before it snaps,

shot in the back of the head.

"This is how you’ll end too; just lie quietly here,"

I whispered to myself, patience blossoming from dread.

"Der springt noch auf," the voice above me jeered;

I could only dimly hear

through the congealing blood slowly sealing my ear.

Translator's note:

"Der springt noch auf" means something like "That one is still twitching."

For many years now I have been editing, publishing and translating Holocaust poetry. In my opinion Miklós Radnóti is the

greatest of the Holocaust poets. But this truly great poet became a victim of ethic cleansing, genocide and war. Unfortunately, ethnic

cleansing, genocide and war still continue to this day. If you are a student, teacher, educator, peace activist or just someone who cares and

wants to help, please consider doing everything you can to help end such atrocities forever. Doing all you can will help make the world a safer, happier

place for people of all races and creeds.

It seems the fourth and final Postcard poem above was the last poem written by Miklós Radnóti. Here are some additional biographic notes,

provided by two of his translators, Peter Czipott and John Ridland: "In a small cross-ruled notebook, procured during his labor in Bor, Serbia,

he continued to write poems. As the Allies approached the mine where he was interned, he and his brigade were led on a forced march toward

northwest Hungary. Laborers who straggled—from illness, injury or exhaustion—were shot by the roadside and buried in mass graves.

Number 4 of the "Razglednicak" poems was written on October 31, the day that Radnóti's friend, the violinist Miklós Lovsi, suffered

that fate. It is the last poem Radnóti wrote. On November 9, 1944, near the village of Abda, he too was shot on the roadside by guards who were

anxious to reach their camp by nightfall. Buried in a mass grave, his body was exhumed over a year later, and the coroner's report mentions

finding the "Bor Notebook" in the back pocket of his trousers. Radnóti had made fair copies of all but five poems while in Bor, and

those had been smuggled out by a survivor. When his widow Fanni received the notebook, most of the poems had been rendered illegible, saturated

by the liquids of decaying flesh. However, the only poems not smuggled out—the four Razglednicas and one other—happened to be the only

ones still decipherable in their entirety in the notebook. In late summer 1937, Radnóti had made his second visit to France, accompanied

by Fanni. Although this was a year before Kristallnacht, Hitler's move into Czechoslovakia, and the first discriminatory "Jewish Law"

in Hungary, there was plenty of "terrible news" in the papers, as mentioned in "Place de Notre Dame": the Spanish Civil

War, the Japanese invasion of China, and of course the increasing threats from Hitler's Germany. Nevertheless, most of these poems, at

least on the surface, are innocent snapshots that justify their French title, referring to picture postcards such as tourists mail home.

Radnóti was likely alluding ironically to this earlier set with his final four poems, which have the Serbian word for postcard—in a Hungarian

plural form—as their title. Reading the two sets together darkens the tones of the five earlier poems, and makes the later four all the more

poignant."

As Camille Martin wrote, "These last poems, written under the pressure of the most degrading and desperate

circumstances imaginable, unfurl visions of delicate pastoral beauty next to images of extreme degradation and wild, filthy despair. They give

voice to the last vestiges of hope, as Radnóti fantasizes being home once more with his beloved Fanny, as well as to the grim premonition of

his own fate. This impossibly stark contrast blossoms into paradox: Radnóti’s poetry embraces humanity and inhumanity with an urgent desire to

bear witness to both. Yet even at the moment when he is most certain of his imminent death, he never abandons the condensed and intricate

language of his poetry. And pushed to the limits of human endurance and sanity, he never loses his capacity for empathy."

Speechless

by Ko Un

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

At Auschwitz

piles of glasses

mountains of shoes

returning, we stared out different windows.

This is one of the most powerful and disturbing Holocaust poems ...

Death Fugue

by Paul Celan

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

Black milk of daybreak, we drink you come dusk;

we drink you come midday, come morning, come night;

we drink you and drink you.

We’re digging a grave like a hole in the sky;

there’s sufficient room to lie there.

The man of the house plays with vipers; he writes

in the Teutonic darkness, “Your golden hair Margarete ...”

He composes by starlight, whistles hounds to stand by,

whistles Jews to dig graves, where together they’ll lie.

He commands us to strike up bright tunes for the dance!

Black milk of daybreak, we drink you come dusk;

we drink you come dawn, come midday, come night;

we drink you and drink you.

The man of the house plays with serpents; he writes ...

he writes as the night falls, “Your golden hair Margarete ...

Your ashen hair Shulamith ...”

We are digging dark graves where there’s more room, on high.

His screams, “Hey you, dig there!” and “Hey you, sing and dance!”

He grabs his black nightstick, his eyes pallid blue,

screaming, “Hey you—dig deeper! You others—sing, dance!”

Black milk of daybreak, we drink you come dusk;

we drink you come midday, come morning, come night;

we drink you and drink you.

The man of the house writes, “Your golden hair Margarete ...

Your ashen hair Shulamith ...” as he cultivates snakes.

He screams, “Play Death more sweetly! Death’s the master of Germany!”

He cries, “Scrape those dark strings, soon like black smoke you’ll rise

to your graves in the skies; there’s sufficient room for Jews there!”

Black milk of daybreak, we drink you come midnight;

we drink you come midday; Death’s the master of Germany!

We drink you come dusk; we drink you and drink you ...

He’s a master of Death, his pale eyes deathly blue.

He fires leaden slugs, his aim level and true.

He writes as the night falls, “Your golden hair Margarete ...”

He unleashes his hounds, grants us graves in the skies.

He plays with his serpents; Death’s the master of Germany ...

“Your golden hair Margarete ...

your ashen hair Shulamith ...”

"Do not stand at my grave and weep" is a Holocaust poem and elegy with a very

interesting genesis, written

in 1932 by Mary Elizabeth Frye (1905-2004). Although the origin of the poem was disputed

for some time, Mary Frye's authorship was confirmed in 1998 after research by Abigail Van Buren,

the newspaper columnist better known as "Dear Abby." The version below was published by

The Times and The Sunday Times in

Frye's obituary on November 5, 2004. Frye wrote the poem in 1932. As far as we know, she

had never written any poetry before, but the plight of a young German Jewish woman,

Margaret Schwarzkopf, who was staying with her and her husband at the time, inspired the

poem. Schwarzkopf had

been concerned about her mother, who was ill in Germany, but she had been warned

not to return because of increasing anti-Semitic unrest that was erupting into

what later became known as the Holocaust.

When her mother

died, the heartbroken young woman told Frye that she never had the chance to

"stand by my mother's grave and shed a tear." Frye found herself composing a

piece of verse on a brown paper shopping bag. Later she said that the words

"just came to her" and expressed what she felt about life and death.

Excerpts from "A Page from the Deportation Diary"

by Wladyslaw Szlengel

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

I saw Janusz Korczak walking today,

leading the children, at the head of the line.

They were dressed in their best clothes—immaculate, if gray.

Some say the weather wasn’t dismal, but fine.

They were in their best jumpers and laughing (not loud),

but if they’d been soiled, tell me—who could complain?

They walked like calm heroes through the haunted crowd,

five by five, in a whipping rain.

The pallid, the trembling, watched from high overhead,

through barely cracked windows—pale, transfixed with dread.

And now and then, from the high, tolling bell

a strange moan escaped, like a sea gull’s torn cry.

Their “superiors” looked on, their eyes hard as stone.

So let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

Footfalls... then silence... the cadence of feet...

O, who can console them, their last mile so drear?

The church bells peal on, over shocked Leszno Street.

Will Jesus Christ save them? The high bells career.

No, God will not save them. Nor you, friend, nor I.

But let us not flinch, as they march on, to die.

No one will offer the price of their freedom.

No one will proffer a single word.

His eyes hard as gavels, the silent policeman

agrees with the priest and his terrible Lord:

“Give them the Sword!”

At the great town square there is no intervention.

No one tugs Schmerling’s sleeve. No one cries

“Rescue the children!” The air, thick with tension,

reeks with the odor of vodka, and lies.

How calmly he walks, with a child in each arm:

Gut Doktor Korczak, please keep them from harm!

A fool rushes up with a reprieve in hand:

“Look Janusz Korczak—please look, you’ve been spared!”

No use for that. One resolute man,

uncomprehending that no one else cared

enough to defend them,

his choice is to end with them.

Ninety-Three Daughters of Israel

a Holocaust poem

by Chaya Feldman

loose translation/interpretation by Michael R. Burch

We washed our bodies

and cleansed ourselves;

we purified our souls

and became clean.

Death does not terrify us;

we are ready to confront him.

While alive we served God

and now we can best serve our people

by refusing to be taken prisoner.

We have made a covenant of the heart,

all ninety-three of us;

together we lived and learned,

and now together we choose to depart.

The hour is upon us

as I write these words;

there is

barely enough time to transcribe this prayer ...

Brethren, wherever you may be,

honor the Torah we lived by

and the Psalms we loved.

Read them for us, as well as for yourselves,

and someday when the Beast

has devoured his last prey,

we hope someone will say Kaddish for us:

we

ninety-three daughters of Israel.

Amen

In 1943 Meir Shenkolevsky, the secretary of the world Bais Yaakov movement and a

member of the Central Committee of Agudas Israel in New York, received a letter

from Chaya Feldman: "I don't know when you will

get this letter and if you still will remember me. When this letter arrives, I

will no longer be alive. In a few hours, everything will be past. We are here in

four rooms, 93 girls ages 14 to 22, all of us Bais Yaakov teachers. On July 27,

Gestapo agents came, took us out of our apartment and threw us into a dark room.

We only have water to drink. The younger girls are very frightened, but I comfort

them that in a short while, we will be together with our mother Sara [Sara Shnirer, the founder of the Bais Yaakov Seminary]. Yesterday they took us out,

washed us and took all our clothes. They left us only shirts and said that

today, German soldiers will come to visit us. We all swore to ourselves that we

will die together. The Germans don't know that the bath they gave us was the

immersion before our deaths: we all prepared poison. When the soldiers come, we

will drink the poison. We are all saying Viduy throughout the day. We are not

afraid of anything. We only have one request from you: Say Kaddish for 93 bnos

Yisroel! Soon we will be with our mother Sara. Signed, Chaya Feldman from

Cracow."

Do not stand at my grave and weep

by Mary Elizabeth Frye

Do not stand at my grave and weep,

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

I am the soft star-shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.

Carl Sandburg is one of America's best-known penners of free verse.

Here "grass" may refer to Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, in which the

first great American free verse poet suggests that, if we want to find him after his

death, we can look for him under our boot soles!

Grass

by Carl Sandburg

Pile the bodies high at Austerlitz and Waterloo.

Shovel them under and let me work―

I am the grass; I cover all.

And pile them high at Gettysburg

And pile them high at Ypres and Verdun.

Shovel them under and let me work.

Two years, ten years, and the passengers ask the conductor:

What place is this?

Where are we now?

I am the grass.

Let me work.

Pity Us

by Samuel Menashe

Pity us

Beside the sea

On the sands

So briefly

O Lady

by Samuel Menashe

O Lady lonely as a stone―

Even here moss has grown

Survival

by Samuel Menashe

I stand on this stump

To knock on wood

For the good I once

Misunderstood

Cut down, yes

But rooted still

What stumps compress

No axe can kill

Daily Bread

by Samuel Menashe

I knead the dough

Whose oven you stoke

We consume each loaf

Wrapped in smoke

The Family Silver

by Samuel Menashe

That spoon fell out

Of my mother's mouth

Before I was born,

But I was endowed

With a tuning fork

Samuel Menashe was born Samuel Menashe Weisberg, the child of persecuted Ukrainian Jews who

emigrated to

New York, living in Brooklyn and Queens. His first language was Yiddish. Menashe served in the military during World War II,

where he experienced and survived brutal combat, including the Battle of the Bulge,

which affected his worldview forever: "For the first few years after the war,

each day was the last day. And then it changed. Each day was the only day." I'm not sure if

all the poems above are specifically about the Holocaust, per se, but I think

they serve well whatever their roots.

January 27, 2023: The Numb Heart

by Bob Zisk

The architecture, drab, decays in silence,

Except for wind that shakes the teetering balance

Of Themis. Under onyx wings of ravens

Whose squawks protest indifference in the heavens,

God and Satan nod in disbelief,

And Furies muffle screams of useless grief.

Themis was the goddess and personification of wisdom, justice, law and order,

fairness, and custom. Her symbols include the famous Scales of Justice.

Something

by Michael R. Burch

for the children of the Holocaust and the Nakba

Something inescapable is lost—

lost like a pale vapor curling up into shafts of moonlight,

vanishing in a gust of wind toward an expanse of stars

immeasurable and void.

Something uncapturable is gone—

gone with the spent leaves and illuminations of autumn,

scattered into a haze with the faint rustle of parched grass

and remembrance.

Something unforgettable is past—

blown from a glimmer into nothingness, or less,

and finality has swept into a corner where it lies

in dust and cobwebs and silence.

Unnecessary cruelty and brutality are horrible enough, but when

innocent children are the victims, words begin to fail us. The poem "Something" tries to capture something of the heartbreaking loss of young

lives cut short, even as the poet admits his inability to do anything more than preserve a

brief flicker of remembrance, an increasingly ethereal memory. What happened to millions of children during

the Holocaust was a horror beyond imagining. Children who had been "born wrong"

according to the Nazis—whether Jewish, Polish, Gypsy, Slavic, Russian or otherwise

"inferior"—were either killed outright or stripped of their human rights and

consigned to abysmal conditions in concentration camps and walled ghettoes. But

as the poem below points out, even to this day completely innocent

children continue to be stripped of their human rights and consigned to

abysmal, terrifying conditions in refugee camps

and walled ghettoes, while the world watches and does little or nothing

to help them.

If you are a Christian, or have an interest in such things, you may want to read

Did a

Misinterpretation of the Bible lead to the Trail of Tears, American Slavery and

the Holocaust?

Epitaph for a Child of the Nakba

by Michael R. Burch

I lived as best I could, and then I died.

Be careful where you step: the grave is wide.

The Hebrew word for the Holocaust is Shoah; it means "Catastrophe." The Arabic

word Nakba also means "Catastrophe." Today millions of completely innocent

Palestinian children and their mothers and grandparents languish within the walled ghetto of Gaza, the walled

bantustans of Occupied Palestine (the West Bank) and refugee camps across the

Middle East. Why are people who are obviously not "terrorists" being

collectively punished for the "crime" of having been "born wrong," just as Jews were once collectively punished by the Nazis? If it concerns you that such things continue to happen today,

and in this case are being funded and supported by the government of the United

States, please visit our

Nakba Index and read what great humanitarians and Nobel Peace Prize winners

like Albert Einstein, Mohandas Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Jimmy

Carter have said on the subject. The most

admired Jewish intellectual of all time, the man most responsible for the advent

of modern nonviolent resistance, the two men best known for ending South African

apartheid, and the president who helped negotiate peace between Israel and

Palestinians have all spoken firmly and eloquently against the racism and

injustices that resulted in this new catastrophe,

the Nakba.

The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner

by Randall Jarrell

From my mother's sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

Randall Jarrell was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1914, the year World War I

began. He earned bachelor's and master's degrees from Vanderbilt University,

where he studied under Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom and Allen Tate. In

1942 he enlisted in the Army Air Corps and worked as a control tower operator

during World War II, an experience which influenced and provided material for

his poetry. Jarrell’s reputation as a poet was established in 1945 with the

publication of his second book, Little Friend, Little Friend, which

"bitterly and dramatically documents the intense fears and moral struggles of

young soldiers."

Cleansings

by Michael R. Burch

Walk here among the walking specters. Learn

inhuman patience. Flesh can only cleave

to bone this tightly if their hearts believe

that God is good, and never mind the Urn.

A lentil and a bean might plump their skin

with mothers’ bounteous, soft-dimpled fat

(and call it “health”), might quickly build again

the muscles of dead menfolk. Dream, like that,

and call it courage. Cry, and be deceived,

and so endure. Or burn, made wholly pure.

If one prayer is answered,

“G-d”

must be believed.

No holy pyre this—death’s hissing chamber.

Two thousand years ago—a starlit manger,

weird Herod’s cries for vengeance on the meek,

the children slaughtered. Fear, when angels speak,

the prophesies of man.

Do what you "can,"

not what you must, or should.

They call you “good,”

dead eyes devoid of tears; how shall they speak

except in blankness? Fear, then, how they weep.

Escape the gentle clutching stickfolk. Creep

away in shame to retch and flush away

your vomit from their ashes. Learn to pray.

Other Holocaust Poets

Jewish ghetto poets who wrote Holocaust poems include

Hershele Danielovitch, Mordecai Gebirtig, Hirsh Glik, Chaim Grade, Ber

Horowitz, Shmerke Kaczerginski, Chaim Kaplan, Itzhak Katzenelson,

Moishe (Moshe) Kaufman,

Janusz Korczak, Henryka Łazowertówna,

Kalman Lis,

Itzik Manger,

Peretz

Opochinski, Simkha-Bunim Shayevitch, Yisroel Shtern, Isaiah Spiegel, Abraham

Sutzkever,

Wladyslaw Szlengel,

Miryam

(Miriam) Ulinover,

Itzhak (Yitzkhak) Viner

and Leyzer Volf, among others. Unfortunately in other cases the poems survived

but the poets and their names did not.

Poets, songwriters and bands who opposed racism, fascism and horrors like

the Holocaust include Joan Baez, William Blake, Robert Burns, Jimmy Cliff, Sam

Cooke ("A Change is Gonna Come"), Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Woody Guthrie (who

inscribed "This machine kills fascists" on his guitar), George Harrison, Joe

Hill, Billie Holliday ("Strange Fruit"), Langston Hughes, Janis Ian, Michael

Jackson ("Man in the Mirror"), Billy Joel ("Saigon"), Dr. Martin Luther King

Jr., Paul McCartney, Robinson Jeffers, John Lennon (who wrote "Imagine" and

"Revolution"), Melanie Safka, Phil Ochs, Midnight Oil ("Beds Are Burning"), Paul

Robeson, Pete Seeger, Paul Simon, Sly & the Family Stone, Bruce Springsteen,

Edwin Starr ("War"), Cat Stevens ("Peace Train"), Sting ("Russians"), U2, Tom

Waits, Walt Whitman, Stevie Wonder and Neil Young ("Let's Impeach the

President")

Holocaust Poetry, Testimonies and Essays by Holocaust Victims and Survivors,

and Great Humanitarians

Miklos Radnoti

(translations of a Hungarian Jewish poet; perhaps the greatest of the Holocaust

poets)

Terezín Children's Holocaust Poems

(poems by child poets of a Nazi concentration camp)

Martin Niemöller (he

wrote the most famous of all Holocaust poems: "First they came for the

Jews ...")

Einstein

on Palestine

(Albert Einstein was both a victim and survivor of the

Holocaust)

Mahmoud Darwish

(the preeminent Palestinian Holocaust poet of his day)

Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II) (poetry by Pope John

Paul II, a Holocaust victim and survivor)

Paul Celan

(translations of a German Jewish poet, including his famous poem "Todesfuge"

or "Death Fugue")

The Ghetto

Poets (translations of Polish Jewish ghetto poets by Yala Korwin)

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (revisit the ringing words of the man whose

impossible dream of equality became a reality)

Mohandas Gandhi (please read and consider what the great advocate of non-violent

resistance had to say about the Nakba)

As you explore these pages, please keep in mind that if Jews, Gypsies, Slavs,

homosexuals and other people deemed "inferior" by the Nazis had not been denied

access to fair laws and courts, the Holocaust could never have happened. The Holocaust was, essentially, a

failure of justice that led to the disintegration of the moral foundations of

society. In order to prevent other Holocausts, we must ensure that every

child is protected by fair laws and courts. There can be no

exceptions, because every exception begins life as a

defenseless

baby. And so please pay particular attention to our

Nakba pages, because

while the Nazi Holocaust has thankfully ended, multitudes of innocent

children are now suffering and dying in this new Holocaust.

Now is the time to ensure that all

children are protected by equal rights, fair laws and fair courts. Then we can

write celebratory poetry, rather than mournful laments and dirges.

Reuven Moskovitz (a Jewish Holocaust survivor who received the Mount Zion

Award and the Aachen Peace Prize)

Bertolt Brecht

(a German poet who opposed the Nazis)

Avraham Burg: the

Prophet-Poet of Judaism (Holocaust writings by a Jewish politician and peace

activist)

Dahlia Ravikovitch (Holocaust poetry by one of Israel's foremost poets)

What I learned from Elie Wiesel and other Jewish Holocaust Survivors (an essay by Michael R. Burch)

Dan Almagor (a Holocaust poem by an Israeli poet)

Bronislawa Wajs "Papusza" (one translation of a Romani Gypsy poet, by Yala

Korwin)

Iqbal Tamimi (a Palestinian poet who lives in exile, dreaming of a free,

independent, democratic Palestine)

If you are a student, teacher, educator, peace

activist or just someone who cares and wants to help, please read two very

important articles:

What Was

the Holocaust and Why Did It Happen?

and

How Can We End Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide Forever?

If you want to do something to end one of the worst ongoing holocausts, and help

prevent such things from ever happening again, please read and consider

supporting the Burch-Elberry Peace Initiative.

Associated Pages: Hiroshima, 9-11, the NAKBA, Darfur, the Trail of Tears, Bosnia,

etc.

Ogaden Poetry

Japan Earthquake/Tsunami Poetry

Hiroshima Poetry, Prose and

Art

9-11 Poetry

Child of 9-11, a poem for

Christina-Taylor Green

"The Whirlwinds of Revolt will continue to Shake the Foundations of our Nation

..."

The Children of Gaza Speak

Frail Envelope of Flesh, a poem for the children of

Gaza

Poems

for Gaza

At Death's

Door: a Story of Gaza

The Nakba

("Catastrophe"): The Holocaust of the Palestinians

Palestinian Poetry, Art and Photography

Night Labor, a poem for Rachel Corrie, a young peace activist who

died in Rafah

Vanessa Redgrave: A Passion for Justice

In the Shadow of Rachel's Tomb

Who the hell was Furkan

Dogan, and why should we care?

"Does Jesus Love Me?"

For

Darfur: Poetry about the Holocaust and Genocide in Darfur

Bloodshed in the Sahara: the Plight of the Sahrawi People

Poems for Haiti

The Holocaust of the

Homeless

The

Trail of Tears

Nadia Anjuman: the personal

holocaust of an Afghani poet

David Burnham's

"Bosnian Morning"

Le Trio Joubran

In Peace's Arms, Not War's: the Poets speak for Peace, not War

Other

Holocaust Poets, Writers and Artists

Dr.

Hanan Ashrawi (poems by a tireless campaigner for Palestinian human rights)

Peggy Landsman

(Holocaust poetry by an American poet who was touched by pictures of the "little

boy with his hands up")

Yala Korwin (Holocaust

poetry and art by a Jewish Holocaust survivor)

Salomon N.

Meisels (translations of her father's poems by Yala Korwin)

Anita Dorn (poems

by an

Estonian poet who fled the advancing Red Armies as a young girl)

Takashi Tanemori (poems, prose and art by a Hiroshima survivor)

Chaya Feldman (she wrote one of the most poignant poems of the Holocaust:

"93 Daughters of Israel")

Tawfik Zayyad

(a Palestinian poet)

Fadwa

Tuqan (she has been called the Grand Dame of Palestinian poets)

Nahida Izzat (a

Jerusalem-born Palestinian refugee who has lived in exile for over forty years)

A Page from the Deportation Diary (a poem about Janusz Korczak by Wladyslaw

Szlengel)

Wladyslaw Szlengel (translations of a Jewish poet who died in the Warsaw

ghetto)

Janusz Korczak (translations of a hero of the Holocaust by Esther Cameron)

Primo Levi

(translations of an Italian Jewish Holocaust survivor)

Anthony Hecht (a poet of

German-Jewish descent who helped liberate a concentration camp)

Nakba

(the pseudonym of a Palestinian American poet who speaks

very bluntly about his people's plight)

Ber Horvitz

(an unknown Jewish Holocaust poet who can only be known today by the poems he

left us)

Miryam

(Miriam) Ulinover (a Jewish writer who

wrote prose in Polish, German and Russian and poetry in Yiddish)

Itzhak (Yitzkhak) Viner

(translations of a Polish Jewish poet who was imprisoned in the Lodz Ghetto)

Jerzy Ficowski

(translations of a Polish Christian poet by Yala Korwin)

Vilem

Pollak (one translation of a Czech poet by Martin Rocek and Colin Ward)

Allama Iqbāl

(translations of a poet who is considered by many to be the founder of the

modern state of Pakistan)

Moishe (Moshe) Kaufman (a

Jewish Holocaust survivor who fled to Buenos Aires)

Peretz

Opochinski (he began writing poetry at age twelve, only to die in the Warsaw

Ghetto along with his wife and child)

Gideon Levy (he has been called the "most hated man in Israel," for speaking

out against an ongoing holocaust, the Nakba)

Hershele Danielovitch (two Holocaust poems by a Jewish poet who died in the Warsaw

Ghetto)

Kalman Lis (a poem by a Polish Jew who died during the Holocaust)

Kim Nguyen

(two letters about the suffering of Palestinians at the hands of Israeli

settlers and the IDF)

Saul Tchernichovsky

(two poems by a Russian Jew who immigrated to Palestine)

Contemporary Poets and other Writers on the Holocaust

Yakov Azriel (a Holocaust poem by an Israeli poet)

Peter Austin

(Holocaust poetry by an American poet)

Michael R. Burch (Holocaust poetry by an American poet)

Charles Adés

Fishman (Holocaust poetry by an American poet)

Dr. John Z.

Guzlowski (Holocaust poetry by an American poet)

Roger Hecht (a Holocaust

poem by an American poet)

Christina

Pacosz (Holocaust poems by an American poet)

Elie Wiesel (Holocaust

essays by a Nobel Peace Prize laureate)

Joseph

McDonough (poetry by a stockbroker who worked in the World Trade Center

prior to 9-11)

Edward Nudelman

(a Holocaust poem by an American poet)

Sean M. Teaford (Holocaust poems by an American poet)

Students on the Holocaust (and Holocausts of Students)

Brian Coleman (a tribute page to an American student who reached out to Holocaust survivors)

Fardin Mohammadi (a Muslim student writes about his feelings on the anniversary of 9-11)

Holocaust Poetry and Art (Holocaust poetry and art by students Victoria Lassen and Meidema Sanchez)

Parkland Poems (poems about the massacre of students at a Parkland, Florida high school)

Sandy Hook Poems (poems about the

massacre of students at Sandy Hook Elementary School)

Aurora Poetry (poems about the massacre in

Aurora, Colorado)

Columbine Poems (poems about the Columbine

massacre)

Other Holocaust Writings

The Path to Peace in the Middle East

Wrestling Angels and Chimeras

Roll Call of Shame

The Aftermath of the Flotilla

Independence Day Madness

Osama bin Laden and the Twin Terrors

The Curious Blindness of Abba Eban

Israeli Apartheid

How Palestine Became Divided

Logic 101

Parables of Zion

Best Poems about the

Holocaust

Main Index

The HyperTexts