The HyperTexts

The Best Writing in the English Language

This page examines the best writing in the English

language. It attempts to answer questions such as: Which authors wrote the best

poems, the best novels, the best short stories, the best plays, the best essays?

Who produced the best translations?

A thing of beauty is a joy forever.

Its loveliness increases; it will never

pass into nothingness ...

―John Keats

My top ten traditional poets are William Blake, Robert Burns, John Donne, Robert

Frost, A. E. Housman, Wilfred Owen, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Wordsworth,

Sir Thomas Wyatt and William Butler Yeats.

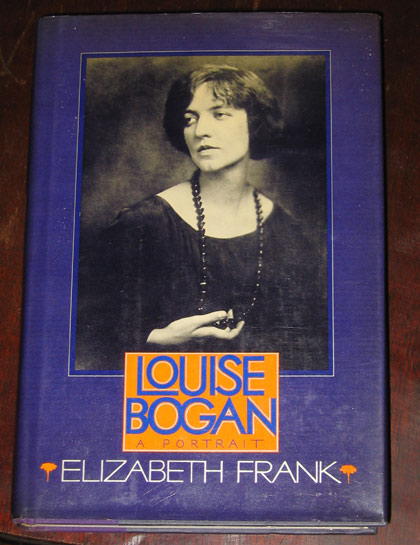

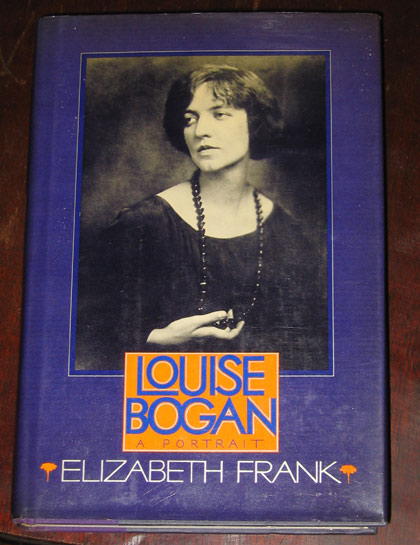

My top ten free verse poets are Louise Bogan, Hart Crane, e. e. cummings, Emily

Dickinson, T. S. Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens,

Dylan Thomas and Walt Whitman.

My top ten novelists are Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, E. L. Doctorow, William

Faulkner, Thomas Hardy, Herman Melville, Ayn Rand, John Steinbeck, J. R. R.

Tolkien and Mark Twain.

My top ten writers of short stories are Agatha Christie, Joseph Conrad, Arthur

Conan Doyle, Nathaniel Hawthorne, James Joyce, Rudyard Kipling, Flannery

O'Connor, Edgar Allan Poe, Ernest Hemingway, H. G. Wells

My top ten playwrights are Samuel Beckett, Noel Coward, Ben Jonson, Christopher

Marlowe, Arthur Miller, Eugene O'Neill, William Shakespeare, George Bernard

Shaw, Tennessee Williams and Oscar Wilde.

My top ten essayists/critics are Francis Bacon, James Baldwin, Harold Bloom,

Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Hazlitt, Dr. Samuel Johnson,

Walter Pater, Bertrand Russell and Mark Twain.

My top ten most influential writers are King Alfred the Great, William Blake,

Geoffrey Chaucer, John Milton, Edgar Allan Poe, William Shakespeare, Edmund

Spenser, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and William Wordsworth.

Here you will also find the poetry and prose of Lord Byron, Geoffrey Chaucer,

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Ernest Dowson, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Robert Herrick,

Langston Hughes, Henry James, John Keats, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edna St.

Vincent Millay, George Orwell, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Edmund Spenser, Alfred Lord Tennyson,

Richard Wilbur and Virginia Woolf.

Because most popular songs are lyric poems set to music, I have included

songwriters like Joan Baez, Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, Eminem, Michael Jackson, John

Lennon, Carole King, Prince, Smokey Robinson, Paul Simon and Bruce Springsteen.

My top writers in translation are Charles Baudelaire, Albert Camus, Miguel de

Cervantes, Anton Chekov, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Albert Einstein, Johann Wolfgang von

Goethe, Herman Hesse, Homer, Victor Hugo, Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, Michel de

Montaigne, Pablo Neruda, Pierre Ronsard, Sappho, Leo Tolstoy, Paul Valery and

Jules Verne.

compiled

by Michael R. Burch

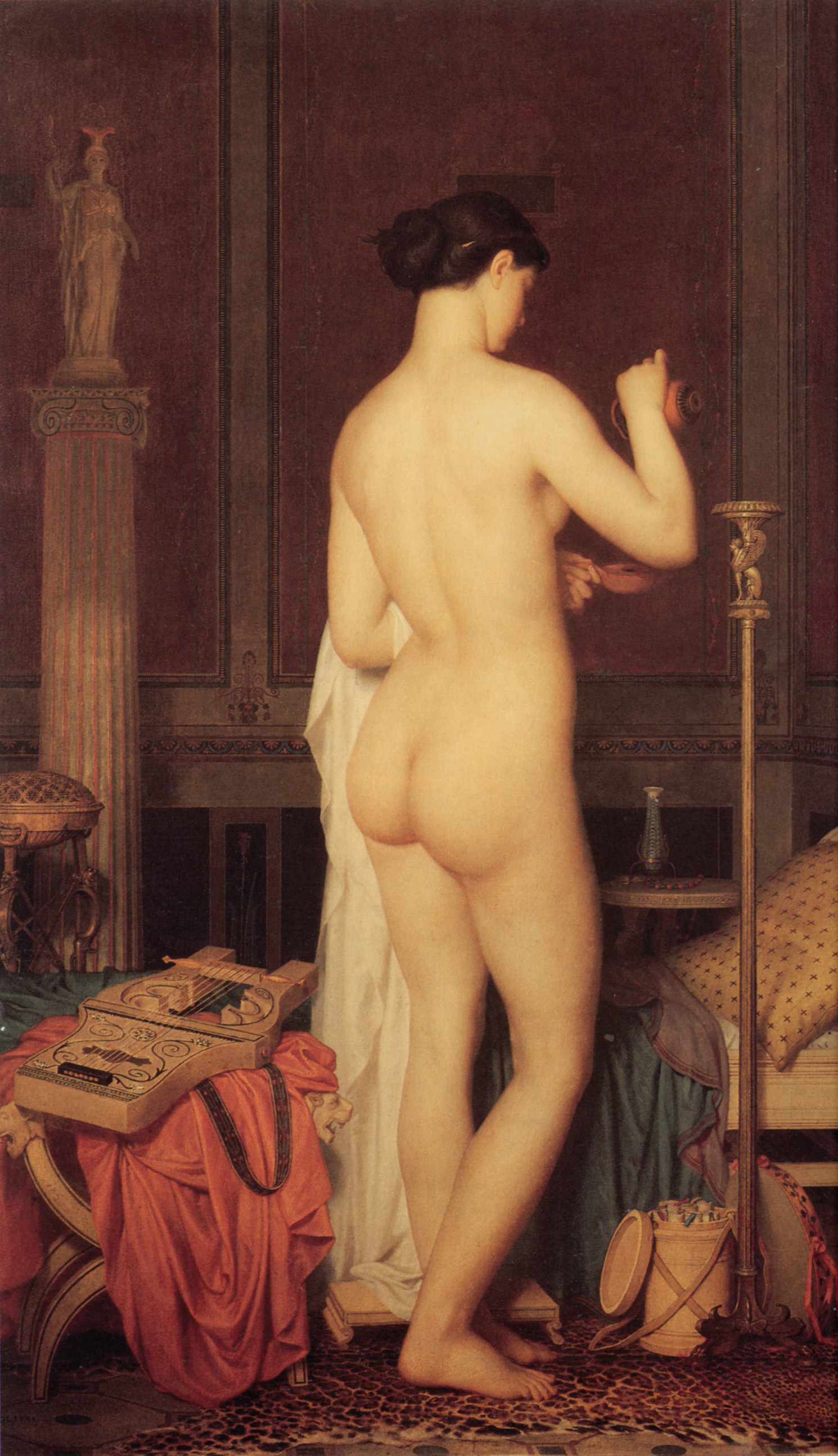

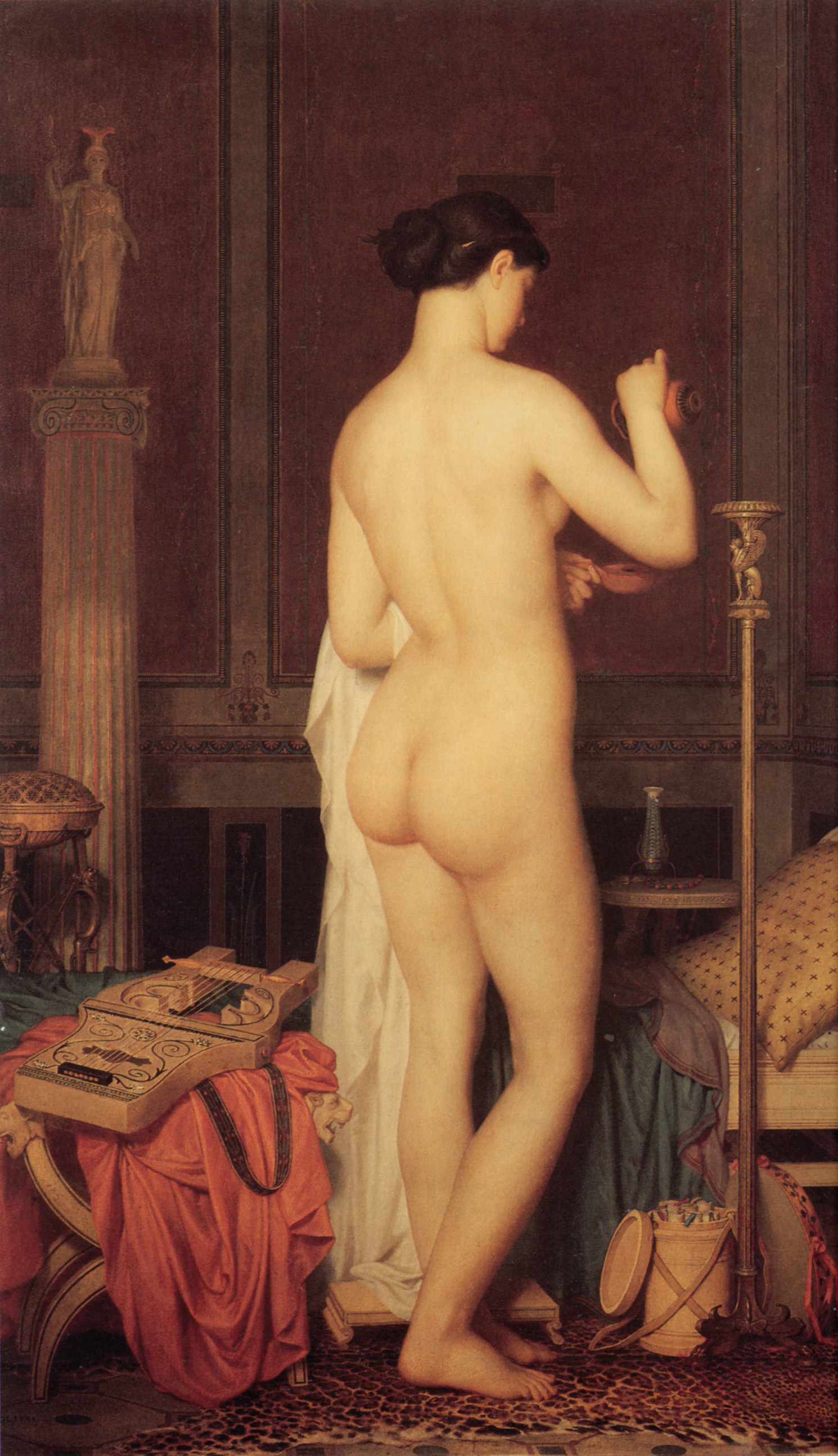

Gleyre Le Coucher de Sappho

by Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre

Sappho of Lesbos (circa 630-570 BC)

Sappho of Lesbos is perhaps the first great female poet still known to us today,

and she remains one of the very best poets of all time, regardless of gender.

She is so revered for her erotic love poetry that we get our terms "sapphic" and

"lesbian" from her name and island of residence. She may be the lyric poet most

translated into English, over the ages. Because the ancient Celts who originally

populated England did not develop writing, we must go back to Sappho and her

lyre for the origin of our word "lyric." Thus, I will invoke her as this page's

Muse.

Sappho, fragment 42

translation by Michael R. Burch

Eros harrows my heart:

wild winds whipping desolate mountains

uprooting oaks.

Sappho, fragment 155

translation by Michael R. Burch

A short revealing frock?

It's just my luck

your lips were made to mock!

Other important writers who predate the English language include Homer (800 BC),

Archilochus (680 BC), Solon (640 BC), Aesop (620 BC), Lao-tse (604 BC), Anacreon

(582 BC), Buddha (563), Confucius (551 BC), Aeschylus (525 BC), Pindar (522 BC),

Pericles (500 BC), Sophocles (497 BC), Euripides (484 BC), Socrates (470 BC),

Plato (428 BC), Aristotle (384 BC), Saint Augustine (354 BC), Julius Caesar (100

BC), Lucretius (99 BC), Cato the Younger (95 BC), Catullus (84 BC), Virgil (70

BC), Horace (65 BC), Plutarch (47 BC), Ovid (43 BC), Martial (43 BC), Lucan (39

BC), Paul of Tarsus (5 BC), Seneca the Younger (4 BC). Many of these dates are

educated guesses. Some of the writers may not have written themselves. For

instance we know about Socrates largely via what Plato wrote about him.

Caedmon (circa 658 AD) and the Anglo-Saxon or Old English Period

(449-1066)

From 55 BC to 410 AD, England had been under Roman control and Latin had become

the language of the elites. The natives were primarily Celts who did not speak

English as we think of the language today. When Visigoths attacked Rome, the

Roman legions were withdrawn from England and Anglo-Saxon invasions of the

island increased. Caedmon is the first major English poet whose name we know,

and he may be "major" mostly because he came first. He was an Anglo-Saxon scop,

or poet. Please keep in mind that he was writing in language closer to German

than to modern English, and that Anglo-Saxon poetry and Old English poetry mean

the same thing: "Hey, this stuff is hard to read!" We have only one poem written

by the first English poet. It was preserved in the writings of the father of

English history, the Venerable Bede. Below is my translation of the first extant

poem in the English language. Each line has a caesura, or pause, which I have

denoted with a small "white space" gap in the middle of each line.

Cædmon's Hymn

translation by

Michael R. Burch

Humbly let us honour heaven-kingdom's Guardian,

the Measurer's might and his mind-plans,

the goals of the Glory-Father. First he, the Everlasting Lord,

established earth's fearful foundations.

Then he, the First Scop, hoisted heaven as a roof

for the sons of men: Holy Creator,

mankind's great Maker! Then he, the Ever-Living Lord,

afterwards made men middle-earth: Master Almighty!

Other English writers of this era, although some of them worked primarily in

Latin, include Gildas, Saint Columba, Cynewulf, Deor, Aldhelm and Bede. This is

also around the probable time of the composition of the Anglo-Saxon epic poem

Beowulf, but its author(s) remain unknown. The authors of the poems

"Wulf and Eadwacer" and "The Wife's Lament" may have been the first female

English poets.

From this point forward, all dates are AD, or current era.

King Alfred the Great (circa 847-886)

King Alfred the Great may have been the first "real" king of a united or

semi-united England. He was an Anglo-Saxon king who defeated Danes (Vikings) who

had been raiding England. Alfred was a learned man, a scholar, and a writer and

translator of note. However, it is not certain whether he did the

bulk of the writing and translation himself. In any case, Alfred was a

patron of public education who ruled that primary education should be in English

rather than Latin, although men in training to become priests would still study

Latin.

Roger Bacon (circa 1219–1292) and the Anglo-Norman or Middle English

Period (1066-1332)

Roger Bacon was called the Doctor Mirabilis ("wondrous doctor"). He was

an English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on

the study of nature through empirical methods or the modern scientific method.

Bacon's linguistic work has been heralded for its early exposition of a

universal grammar. He became a master at Oxford, lecturing on Aristotle, then

taught at the University of Paris. Bacon's major work, the Opus Majus

("Greater Work"), was written in Medieval Latin and sent to Pope Clement IV in

Rome in 1267 at the pope's request. Alas, he was exiled for heresy in 1277!

Notable poets of the Middle English Period: Wace, Layamon, Walter Map, Thomas of

Britain, Guillaume de Lorris, John Gower, William Langland, the

Archpoet, Francesco Petrarch, Dante Alighieri.

Geoffrey Chaucer (circa 1340-1400) and the Late Medieval Period

Geoffrey Chaucer is the first great writer of the English language. In fact, he

has been credited with helping to revive the English language, because before he

chose to write his Canterbury Tales in English, most of the poetry

being composed in England was either French, Latin or Greek! There is little

doubt that Chaucer's development of characters like the Wife of Bath and his "melodizing"

of the English language influenced William Shakespeare and other English writers

to come.

My top ten poets of the Late Medieval Period: Robert Henryson, Thomas Hoccleve,

John Lydgate, William Langland, the Gawain/Pearl poet, John Skelton, John

Gower, Charles D'Orleans, William Dunbar, Geoffrey Chaucer.

Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542) and the English Renaissance (1503-1558)

Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard revolutionized English poetry by introducing

iambic pentameter, blank verse and the sonnet. Wyatt's poems such as "They Flee

From Me" and "Whoso List to Hunt" are masterpieces that can still be read and

enjoyed today. I would nominate Wyatt as the first major modern English poet.

Edmund Spenser (circa 1552-1599)

Edmund Spenser has been credited with creating the modern English style

of poetry: "fluid," "limpid," "translucent" and "graceful." He was the first

"poet's poet" of the English language. His Shepheardes Calender has

been called "the first work of the English literary Renaissance." While he is

best known for his epic-length allegorical poem The Faerie Queene,

Spenser's best work may have been the sonnets that bear his name ("Spenserian")

and his dreamy love poems.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

William Shakespeare is generally considered to be the world's greatest writer.

His literary reputation rests primarily on plays like Hamlet, Macbeth,

Othello, King Lear, The Tempest, Romeo and Juliet, and others. Shakespeare

has also been widely and lavishly praised for his sonnets, although I find his

love sonnets to be overly philosophical and not really convincing. He may have

been writing them for a wealthy patron, so perhaps they weren't meant to be love

poems in the fullest sense. Shakespeare wrote other lyric poems that also don't

rise to the level of his best plays, in my opinion. But Shakespeare did shine as

a songwriter, with the songs from his plays. In my personal canon, Shakespeare

ranks highest for his plays and songwriting.

Other major poets of this era, in addition to Wyatt, Spenser and Shakespeare,

include Christopher Marlowe, Sir Walter Raleigh,

The Romantics (circa 1757-1837)

The Romantics changed the course of English poetry and literature, and probably

the course of Western civilization as well. How they did that is beyond the

scope of this page, but certain things we take for granted today

— the equality of the races and sexes, the idea that

commoners are as good as kings (or don't need them), abhorrence of slavery,

skepticism about the claims of Christianity and other religions, etc. — can be

traced back to the then-revolutionary writings of early Romantics like William

Blake, Robert Burns and Percy Bysshe Shelley. When we talk about the great

English Romantics today, we tend to think of the "Big Six" of Blake, Shelley,

William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron and John Keats. But

there were other Romantics of note: Burns, Thomas Chatterton, Thomas Gray, and

later, across the Atlantic, Walt Whitman and Edgar Allan Poe. They would

influence other Romantics like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles

Swinburne and Ernest Dowson. Eventually Romanticism would blossom into what we

now call Modernism, as poets like Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, William Butler Yeats,

Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Louise Bogan, Dylan Thomas and e. e. cummings took

new liberties with the ancient art of poetry. Today most of the poetry being

written is "free verse," much of it sounding suspiciously like prose, although

the best early Modernists didn't abandon music in their work — they just made

the music less regular.

Felicia Hemans was a child prodigy who had her first book

of poems published at age fourteen. She corresponded with Percy Bysshe Shelley

and was praised in poetic tributes by William Wordsworth and Walter Savage

Landor.

There is in all this cold and hollow world,

no fount of deep, strong, deathless love:

save that within a mother's heart.

―Felicia Dorothea Hemans Browne

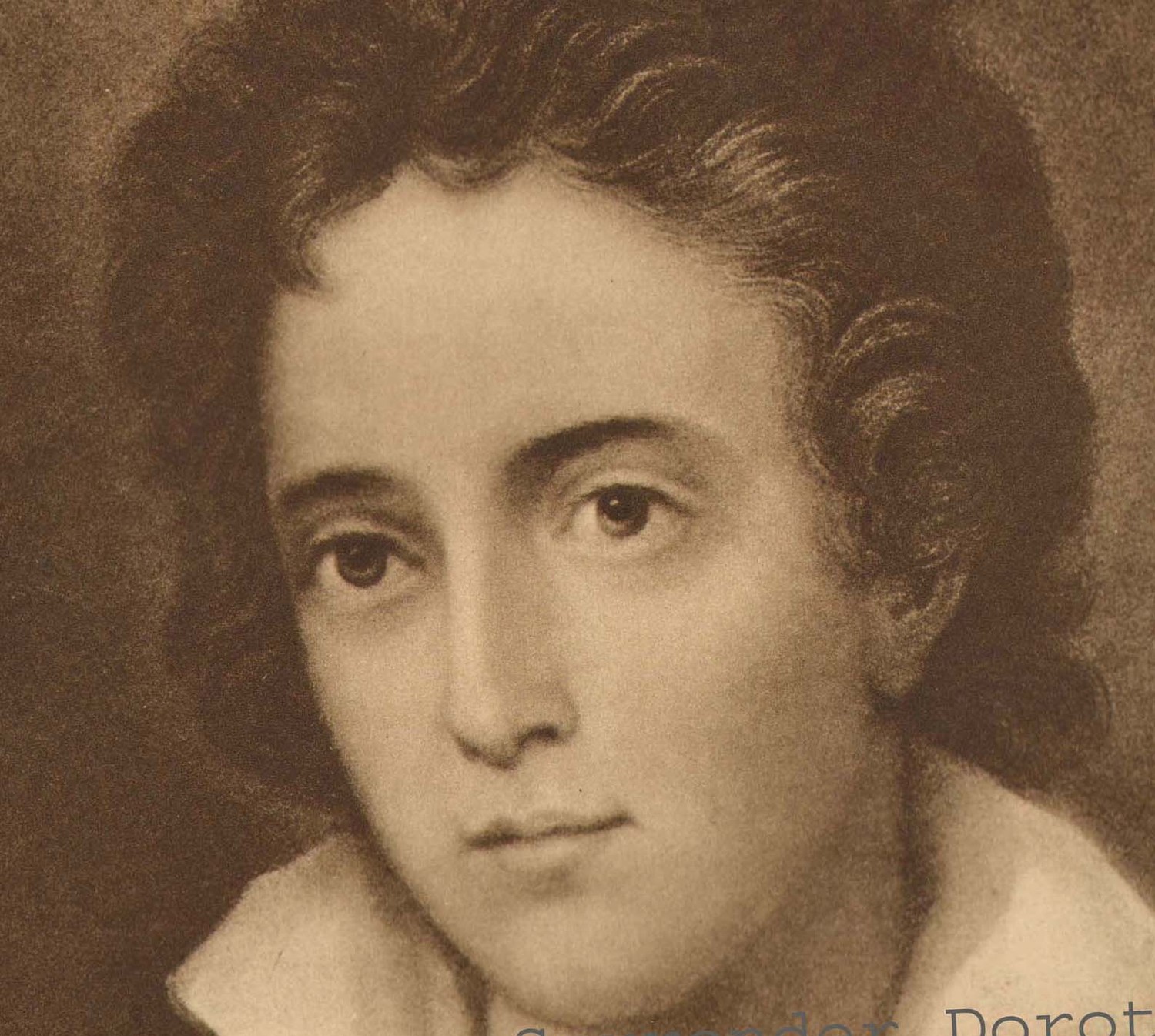

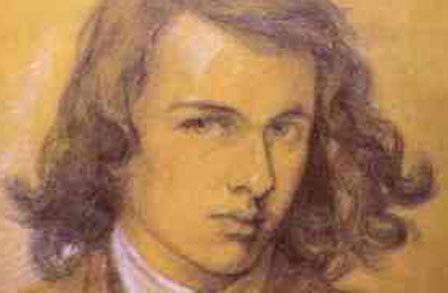

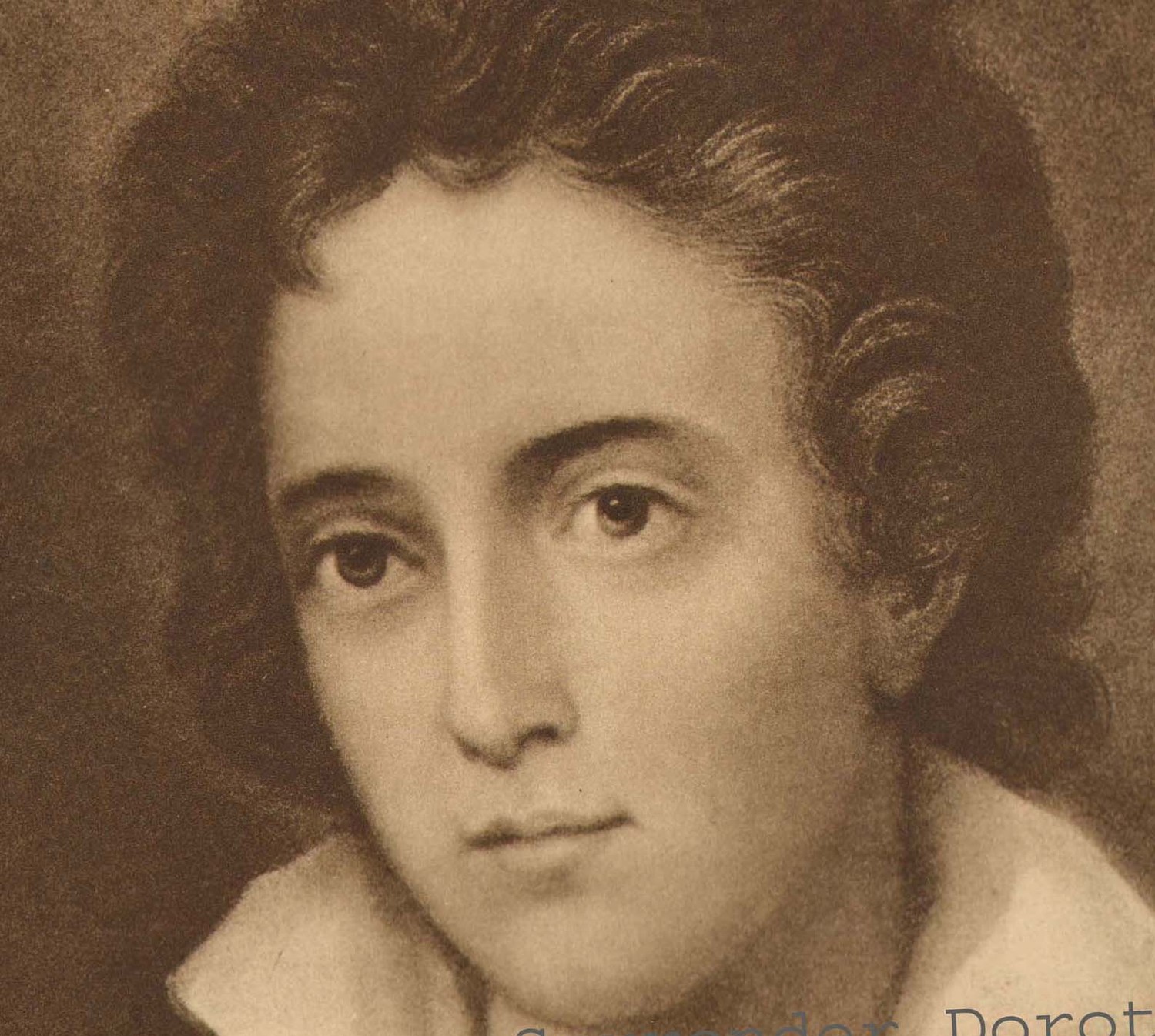

Percy Bysshe Shelley (below) and Felicia Hemans (above) were born a year

apart―he in August 1792, she in September 1793. They look enough alike to be

brother and sister. And it really is a small world, because they were both

poets, both child prodigies, and they corresponded after Hemans had her first

book of poems published.

Percy and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley may have been the most

notorious married couple of their era. He was a dashing romantic poet and

heretic who wrote a tract, "The Necessity of Atheism," that got him expelled

from Oxford. She was the daughter of one of the earliest feminist

writers of note, Mary Wollstonecraft, and the liberal philosopher William

Godwin. The spent the summer of 1816 with Lord

Byron. It was at this time that Mary conceived the story that became her famous

gothic novel Frankenstein. Six years later, her husband drowned at sea at age thirty. Who knows what he would

have accomplished if he had lived longer, but he is still considered to be one

of the greatest English poets. Here is one especially lovely example of his

wonderful touch with rhythm and rhyme:

Music When Soft Voices Die (To

—)

by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory—

Odours, when sweet violets sicken,

Live within the sense they quicken.

Rose leaves, when the rose is dead,

Are heaped for the belovèd's bed;

And so thy thoughts, when thou art gone,

Love itself shall slumber on.

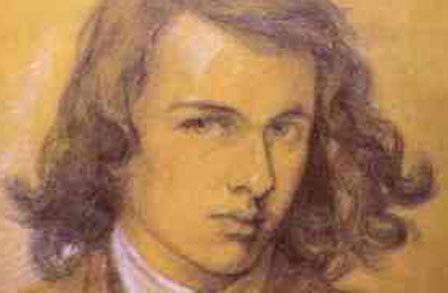

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was an English romantic poet, painter, illustrator

and translator. He was also one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood. His art was characterized by sensuality and medieval revivalism. In

1850 he met Elizabeth Siddal (pictured above), who became his model, his

passion, and eventually in 1860, his wife.

Sudden Light

by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell:

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sighing sound, the lights around the shore.

You have been mine before,—

How long ago I may not know:

But just when at that swallow's soar

Your neck turned so,

Some veil did fall,—I knew it all of yore.

Has this been thus before?

And shall not thus time's eddying flight

Still with our lives our love restore

In death's despite,

And day and night yield one delight once more?

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's sister Christina was also a poet, and perhaps the

better of the two.

Song

by Christina Rossetti

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

Would it surprise you to know that one of the most beautiful (and saddest) poems

in the English language was written by a child prodigy, Thomas Chatterton?

Although his mother and family considered him to be "slow," around age seven the

young Chatterton discovered an ancient book with illuminated capital letters,

and he suddenly became intensely interested, quickly learned to read, and then

began writing poems! By age ten he was a published poet. But many of the poems

he wrote were in a medieval version of English, and no one would believe that a

child was capable of writing such poems. So he pretended to have "found" the

poems of an ancient monk named Thomas Rowley. One thing led to another, and

Chatterton was accused of being a "forger" even though the poems were his

original compositions! Spurned by stuffy literary types and unable to support

himself, but too proud to accept handouts, Chatterton committed suicide at age

17. You can click on his hyperlinked name above to read the sad, lovely ballad

below, and other poems that he wrote during his short, tortured life.

Song from Ælla: Under the Willow Tree, or, Minstrel's Roundelay

by

Thomas Chatterton

...

See! the white moon shines on high;

Whiter is my true-love's shroud:

Whiter than the morning sky,

Whiter than the evening cloud:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

...

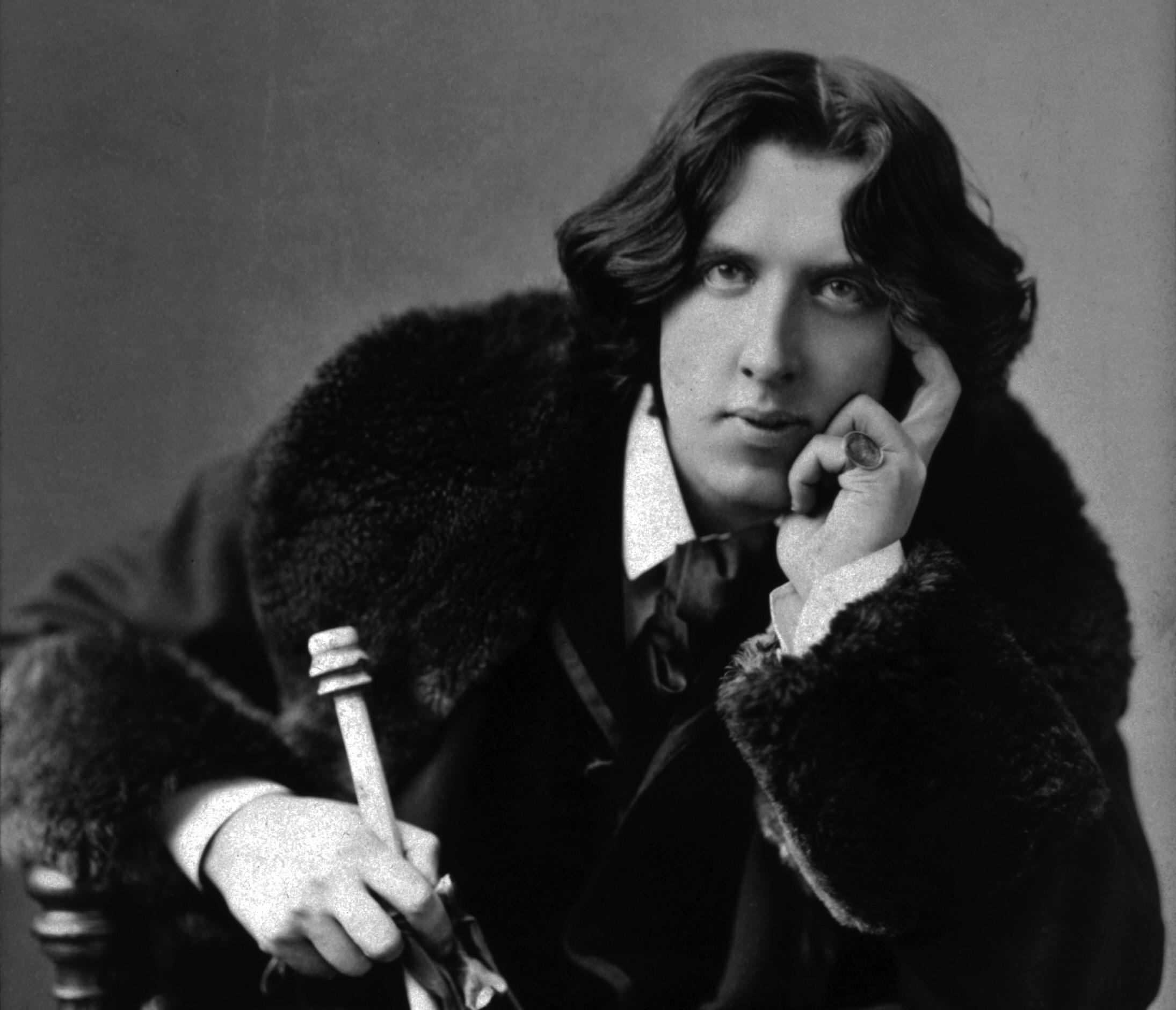

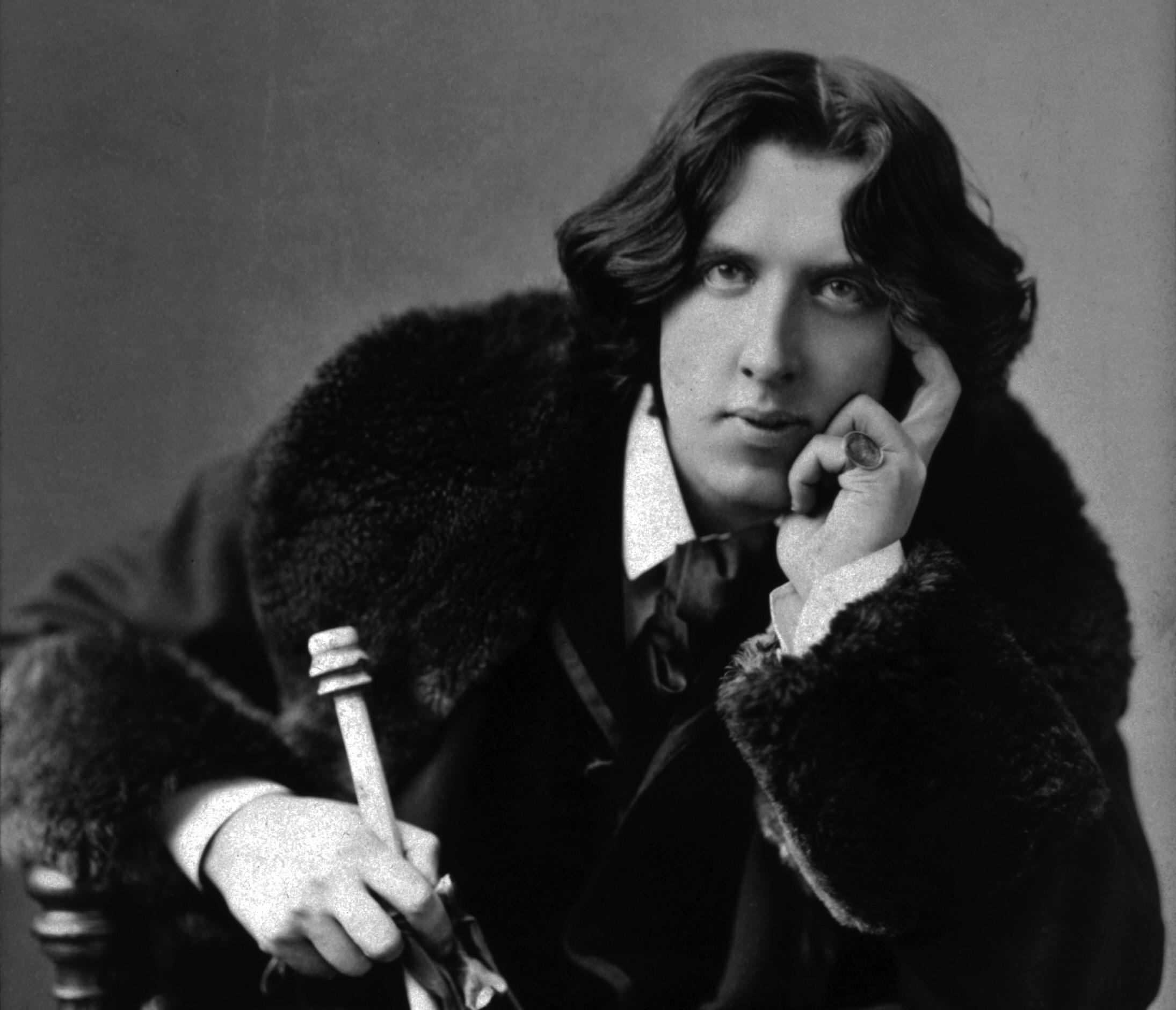

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)

Oscar Wilde, both a Victorian and an early Modernist, may be the most notorious

"bad boy" in the annals of poetry and literature. He was flamboyantly gay at a

time when polite society was prim, proper and violently homophobic. As a result,

he was sentenced to hard labor at Reading Gaol and died soon after his release.

At this point in time, Wilde is best known for his plays The Importance of

Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband, his novella The Picture of

Dorian Gray, his long philosophical letter De Profundis, and his

always witty, sometimes shocking epigrams. But the

lovely, wonderfully moving poem below proves that Oscar

Wilde was also a true poet

capable of

creating timeless art.

Requiescat

by Oscar Wilde

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

All her bright golden hair

Tarnished with rust,

She that was young and fair

Fallen to dust.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

Coffin-board, heavy stone,

Lie on her breast,

I vex my heart alone,

She is at rest.

Peace, Peace, she cannot hear

Lyre or sonnet,

All my life's buried here,

Heap earth upon it.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

William Butler Yeats may have been the last English Romantic and the first

English Modernist, although he was Irish. Yeats was the most famous Irish poet of all time, and his

poems of unrequited love for the beautiful and dangerous revolutionary Maud Gonne

have left her almost as famous. The first poem below is

a

loose translation of a Ronsard poem, in which Yeats imagines the love of his

life in her later years, tending a fire. The second poem, "The Wild Swans

at Coole," is surely one of the most beautiful poems ever written, in any

language.

When You Are Old

by William Butler Yeats

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

The Wild Swans at Coole

by William Butler Yeats

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

Upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine and fifty swans.

The nineteenth Autumn has come upon me

Since I first made my count;

I saw, before I had well finished,

All suddenly mount

And scatter wheeling in great broken rings

Upon their clamorous wings.

I have looked upon those brilliant creatures,

And now my heart is sore.

All’s changed since I, hearing at twilight,

The first time on this shore,

The bell-beat of their wings above my head,

Trod with a lighter tread.

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold,

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

But now they drift on the still water

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake’s edge or pool

Delight men’s eyes, when I awake some day

To find they have flown away?

The Modernists

English Modernism was largely a continuation of English Romanticism. In

the late 1800s and early 1900s there were major breakthroughs in the fields of

psychology and science. Charles Darwin had already published his revolutionary

theory of evolution. Then came Sigmund Freud's Interpretation of Dreams and

Albert Einstein's two theories of relativity. What educated people "knew" was

being shaken to the core. What the Bible said about creation no longer made

sense. Within this climate of change poets like Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot began

to "make it new" ...

But there was not a complete break with the past. Ernest Dowson, who influenced

Eliot, continued to employ traditional English meter and rhyme. Louise Bogan

wrote both formal verse and free verse. Eliot sometimes mixed

traditional-sounding rhymes into his free verse poems. Ezra Pound, who was the

one who had encouraged poets to "make it new" sometimes sounded fashionably

modern, but at other times sounded more archaic than Chaucer.

Song for the Last Act

by Louise Bogan

Now that I have your face by heart, I look

Less at its features than its darkening frame

Where quince and melon, yellow as young flame,

Lie with quilled dahlias and the shepherd's crook.

Beyond, a garden. There, in insolent ease

The lead and marble figures watch the show

Of yet another summer loath to go

Although the scythes hang in the apple trees.

Now that I have your face by heart, I look.

Now that I have your voice by heart, I read

In the black chords upon a dulling page

Music that is not meant for music's cage,

Whose emblems mix with words that shake and bleed.

The staves are shuttled over with a stark

Unprinted silence. In a double dream

I must spell out the storm, the running stream.

The beat's too swift. The notes shift in the dark.

Now that I have your voice by heart, I read.

Now that I have your heart by heart, I see

The wharves with their great ships and architraves;

The rigging and the cargo and the slaves

On a strange beach under a broken sky.

O not departure, but a voyage done!

The bales stand on the stone; the anchor weeps

Its red rust downward, and the long vine creeps

Beside the salt herb, in the lengthening sun.

Now that I have your heart by heart, I see.

Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae

by Ernest Dowson

"I am not as I was under the reign of the good Cynara"—Horace

Last night, ah, yesternight, betwixt her lips and mine

There fell thy shadow, Cynara! thy breath was shed

Upon my soul between the kisses and the wine;

And I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, I was desolate and bowed my head:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

All night upon mine heart I felt her warm heart beat,

Night-long within mine arms in love and sleep she lay;

Surely the kisses of her bought red mouth were sweet;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

When I awoke and found the dawn was gray:

I have been faithful to you, Cynara! in my fashion.

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost lilies out of mind;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, all the time, because the dance was long;

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I cried for madder music and for stronger wine,

But when the feast is finished and the lamps expire,

Then falls thy shadow, Cynara! the night is thine;

And I am desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, hungry for the lips of my desire:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

La Figlia Che Piange (The Weeping Girl)

by T. S. Eliot

Stand on the highest pavement of the stair —

Lean on a garden urn —

Weave, weave the sunlight in your hair —

Clasp your flowers to you with a pained surprise —

Fling them to the ground and turn

With a fugitive resentment in your eyes:

But weave, weave the sunlight in your hair.

So I would have had him leave,

So I would have had her stand and grieve,

So he would have left

As the soul leaves the body torn and bruised,

As the mind deserts the body it has used.

I should find

Some way incomparably light and deft,

Some way we both should understand,

Simple and faithless as a smile and a shake of the hand.

She turned away, but with the autumn weather

Compelled my imagination many days,

Many days and many hours:

Her hair over her arms and her arms full of flowers.

And I wonder how they should have been together!

I should have lost a gesture and a pose.

Sometimes these cogitations still amaze

The troubled midnight, and the noon's repose.

The Garden

by Ezra Pound

Like a skein of loose silk blown against a wall

She walks by the railing of a path in Kensington Gardens,

And she is dying piece-meal

of a sort of emotional anemia.

And round about there is a rabble

Of the filthy, sturdy, unkillable infants of the very poor.

They shall inherit the earth.

In her is the end of breeding.

Her boredom is exquisite and excessive.

She would like some one to speak to her,

And is almost afraid that I

will commit that indiscretion.

Lullaby

by W. H. Auden

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm:

Time and fevers burn away

Individual beauty from

Thoughtful children, and the grave

Proves the child ephemeral:

But in my arms till break of day

Let the living creature lie,

Mortal, guilty, but to me

The entirely beautiful.

Soul and body have no bounds:

To lovers as they lie upon

Her tolerant enchanted slope

In their ordinary swoon,

Grave the vision Venus sends

Of supernatural sympathy,

Universal love and hope;

While an abstract insight wakes

Among the glaciers and the rocks

The hermit's carnal ecstacy.

Certainty, fidelity

On the stroke of midnight pass

Like vibrations of a bell

And fashionable madmen raise

Their pedantic boring cry:

Every farthing of the cost.

All the dreaded cards foretell.

Shall be paid, but from this night

Not a whisper, not a thought.

Not a kiss nor look be lost.

Beauty, midnight, vision dies:

Let the winds of dawn that blow

Softly round your dreaming head

Such a day of welcome show

Eye and knocking heart may bless,

Find our mortal world enough;

Noons of dryness find you fed

By the involuntary powers,

Nights of insult let you pass

Watched by every human love.

Dylan Thomas's elegy to his dying father is one of the best villanelles in the English

language, and it remains one of the most powerful, haunting poems ever

written in any language.

Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

In My Craft Or Sullen Art

by Dylan Thomas

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Not for the proud man apart

From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages

Nor for the towering dead

With their nightingales and psalms

But for the lovers, their arms

Round the griefs of the ages,

Who pay no praise or wages

Nor heed my craft or art.

The Victorians

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was an early advocate of women's rights, and a

staunch opponent of slavery. When she married Robert Browning, theirs became the

most famous coupling in the annals of English poetry.

How Do I Love Thee?

by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love with a passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood's faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints,—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Mary Elizabeth Frye is, perhaps, the most mysterious poet who appears on this

page, and perhaps in the annals of poetry. Rather than spoiling the mystery, I

will present her poem first, then provide the details ...

Do not stand at my grave and weep

by Mary Elizabeth Frye

Do not stand at my grave and weep:

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circling flight.

I am the soft starshine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry:

I am not there; I did not die.

This consoling elegy had a

very mysterious genesis, as it was written by a

Baltimore housewife who lacked a formal education, having been orphaned at age

three. As far as we know, she had never written poetry before. Frye wrote the poem on a ripped-off piece of a brown grocery bag,

in a burst of compassion for a Jewish girl who had fled the Holocaust

only to receive news that her mother had died in Germany. The girl was

weeping inconsolably because she couldn't visit her mother's grave. When the poem was named Britain's

most popular poem in a 1996 Bookworm poll, with more than 30,000

call-in votes despite not having been one of the critics'

nominations, an unlettered orphan girl had seemingly surpassed all England's

many cultured and degreed ivory towerists in the public's estimation. Although the poem's

origin was disputed for some time (it had been attributed to Native American and other sources),

Frye's authorship was confirmed in 1998 after investigative research by Abigail

Van Buren, the newspaper columnist better known as "Dear Abby." The poem has

also been called "I Am" due to its rather biblical repetitions of the phrase.

Frye never formally published or copyrighted the poem, so we believe it is in

the public domain and can be shared, although we recommend that it not be used

for commercial purposes, since Frye never tried to profit from it herself.

Here is a printable version of

Mary Elizabeth Frye's "Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep" which is not

copyrighted and is thus in the public domain.

Edward Thomas is not as well-known as some of the other poets on this page, but

"Adlestrop" was among the top ten most requested poems at Poetry Please,

so he continues to have fans. "Adlestrop" is a somewhat mysterious poem, because

nothing really happens and yet it seems extraordinarily sad.

Adlestrop

by Edward Thomas

Yes. I remember Adlestrop—

The name, because one afternoon

Of heat the express-train drew up there

Unwontedly. It was late June.

The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop—only the name

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

Sir Thomas Wyatt has been credited with introducing the

Petrarchan sonnet into the English language. Wyatt's father had been one of Henry

VII's Privy Councilors and remained a trusted adviser when Henry VIII came to

the throne in 1509. Wyatt followed his father to court, but it seems the

young poet may have fallen in love with the king’s mistress,

Anne Boleyn. Their acquaintance is certain, although whether or not the two

actually shared a romantic relationship remains unknown. But in his poetry, Wyatt called

his mistress Anna and there do seem to be correspondences. For instance, this poem might well have been written

about the King’s claim on Anne Boleyn:

Whoso List to Hunt

by Sir Thomas Wyatt

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,

But as for me, alas, I may no more.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Since in a net I seek to hold the wind.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere, for Caesar's I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

Noli me tangere means "Touch me not." According to the Bible, this is

what Jesus said to Mary Magdalene when she tried to embrace him after the

resurrection. So perhaps after her betrothal to Henry, religious vows

entered into the picture, and left Wyatt out.

Elinor Wylie "was famous during her life almost as much for her ethereal beauty

and personality as for her melodious, sensuous poetry."

Cold-Blooded Creatures

by Elinor Wylie

Man, the egregious egoist

(In mystery the twig is bent)

Imagines, by some mental twist,

That he alone is sentient

Of the intolerable load

That on all living creatures lies,

Nor stoops to pity in the toad

The speechless sorrow of his eyes.

He asks no questions of the snake,

Nor plumbs the phosphorescent gloom

Where lidless fishes, broad awake,

Swim staring at a nightmare doom.

William Dunbar was one of the first great Scottish poets, and is also known for

his poem "Lament for the Makiris" (Lament for the Makers, or Poets).

Sweet Rose of Virtue

by William Dunbar [1460-1525]

loose translation by Michael R. Burch

Sweet rose of virtue and of gentleness,

delightful lily of youthful wantonness,

richest in bounty and in beauty clear

and in every virtue that is held most dear―

except only that you are merciless.

Into your garden, today, I followed you;

there I saw flowers of freshest hue,

both white and red, delightful to see,

and wholesome herbs, waving resplendently―

yet everywhere, no odor but bitter rue.

I fear that March with his last arctic blast

has slain my fair rose of pallid and gentle cast,

whose piteous death does my heart such pain

that, if I could, I would compose her roots again―

so comforting her bowering leaves have been.

Conrad Aiken was one of the sweetest singers among American poets.

Bread and Music

by Conrad Aiken

Music I heard with you was more than music,

And bread I broke with you was more than bread;

Now that I am without you, all is desolate;

All that was once so beautiful is dead.

Your hands once touched this table and this silver,

And I have seen your fingers hold this glass.

These things do not remember you, belovèd,

And yet your touch upon them will not pass.

For it was in my heart you moved among them,

And blessed them with your hands and with your eyes;

And in my heart they will remember always,—

They knew you once, O beautiful and wise.

D. H. Lawrence is better known today for his novels, which include the

then-infamous Lady Chatterley's Lover, but he was one of the better

early modernist poets.

Piano

by D. H. Lawrence

Softly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;

Taking me back down the vista of years, till I see

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom of the tingling strings

And pressing the small, poised feet of a mother who smiles as she sings.

In spite of myself, the insidious mastery of song

Betrays me back, till the heart of me weeps to belong

To the old Sunday evenings at home, with winter outside

And hymns in the cozy parlor, the tinkling piano our guide.

So now it is vain for the singer to burst into clamor

With the great black piano appassionato. The glamour

Of childish days is upon me, my manhood is cast

Down in the flood of remembrance, I weep like a child for the past.

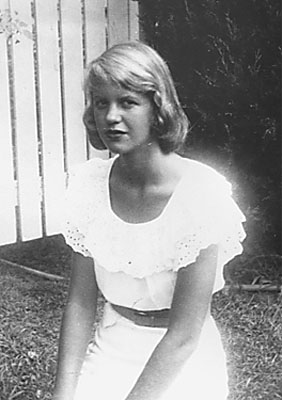

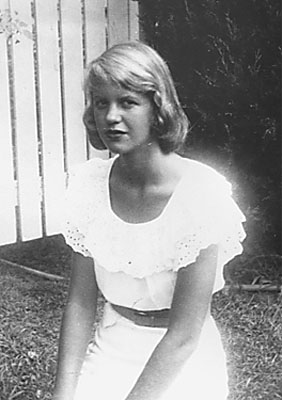

Sylvia Plath was one of the first and best of the modern confessional poets. She

won a Pulitzer Prize posthumously for her Collected Poems after

committing suicide at the age of 31, something she seemed to have been

predicting in her writing and practicing for in real life.

Winter landscape, with rocks

by Sylvia Plath

Water in the millrace, through a sluice of stone,

plunges headlong into that black pond

where, absurd and out-of-season, a single swan

floats chaste as snow, taunting the clouded mind

which hungers to haul the white reflection down.

The austere sun descends above the fen,

an orange cyclops-eye, scorning to look

longer on this landscape of chagrin;

feathered dark in thought, I stalk like a rook,

brooding as the winter night comes on.

Last summer's reeds are all engraved in ice

as is your image in my eye; dry frost

glazes the window of my hurt; what solace

can be struck from rock to make heart's waste

grow green again? Who'd walk in this bleak place?

Anne Sexton was a model who became a confessional

poet, writing about intimate aspects of her life, after her doctor suggested

that she take up poetry as a form of therapy. She studied under Robert Lowell at

Boston University, where Sylvia Plath was one of her classmates. Sexton won the

Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1967, but later committed suicide via carbon

monoxide poisoning. Topics she covered in her poems included adultery,

masturbation, menstruation, abortion, despair and suicide.

The Truth the Dead Know

by Anne Sexton

For my Mother, born March 1902, died March 1959

and my Father, born February 1900, died June 1959

Gone, I say and walk from church,

refusing the stiff procession to the grave,

letting the dead ride alone in the hearse.

It is June. I am tired of being brave.

We drive to the Cape. I cultivate

myself where the sun gutters from the sky,

where the sea swings in like an iron gate

and we touch. In another country people die.

My darling, the wind falls in like stones

from the whitehearted water and when we touch

we enter touch entirely. No one's alone.

Men kill for this, or for as much.

And what of the dead? They lie without shoes

in the stone boats. They are more like stone

than the sea would be if it stopped. They refuse

to be blessed, throat, eye and knucklebone.

Edna St. Vincent Millay was the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for poetry.

She was openly bisexual and had affairs with other women and married men. When

she finally married, hers was an open marriage. Her 1920 poetry collection A

Few Figs From Thistles drew controversy for its novel exploration of female

sexuality. She was one of the earliest and strongest voices for what became

known as feminism. One of the recurring themes of her poetry was that men might

use her body, but not possess her or have any claim over her. (And perhaps that

their desire for her body gave her the upper hand in relationships.)

I, Being Born a Woman, and Distressed

by Edna St. Vincent

Millay

I, being born a woman, and distressed

By all the needs and notions of my kind,

Am urged by your propinquity to find

Your person fair, and feel a certain zest

To bear your body's weight upon my breast:

So subtly is the fume of life designed,

To clarify the pulse and cloud the mind,

And leave me once again undone, possessed.

Think not for this, however, this poor treason

Of my stout blood against my staggering brain,

I shall remember you with love, or season

My scorn with pity — let me make it plain:

I find this frenzy insufficient reason

For conversation when we meet again.

Emily Dickinson was the first great female American poet.

Come Slowly, Eden

by Emily Dickinson

Come slowly—Eden

Lips unused to thee—

Bashful—sip thy jasmines—

As the fainting bee—

Reaching late his flower,

Round her chamber hums—

Counts his nectars—alights—

And is lost in balms!

Go, Lovely Rose

by Edmund Waller

Go, lovely Rose,—

Tell her that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows,

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.

Tell her that's young,

And shuns to have her graces spied,

That hadst thou sprung

In deserts where no men abide,

Thou must have uncommended died.

Small is the worth

Of beauty from the light retir'd:

Bid her come forth,

Suffer herself to be desir'd,

And not blush so to be admir'd.

Then die, that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee;

How small a part of time they share,

That are so wondrous sweet and fair.

VIII — from "Sunday Morning"

by Wallace Stevens

She hears, upon that water without sound,

A voice that cries, "The tomb in Palestine

Is not the porch of spirits lingering.

It is the grave of Jesus, where he lay."

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or old despondency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

Deer walk upon our mountains, and the quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

For Her Surgery

by Jack Butler

I

Over the city the moon rides in mist,

scrim scarred with faint rainbow.

Two days till Easter. The thin clouds run slow, slow,

the wind bells bleed the quietest

of possible musics to the dark lawn.

All possibility we will have children is gone.

II

I raise a glass half water, half alcohol,

to that light come full again.

Inside, you sleep, somewhere below the pain.

Down at the river, there is a tall

ghost tossing flowers to dark water—

jessamine, rose, and daisy, salvia lyrata . . .

III

Oh goodbye, goodbye to bloom in the white blaze

of moon on the river, goodbye

to creek joining the creek joining the river, the axil, the Y,

goodbye to the Yes of two Ifs in one phrase . . .

Children bear children. We are grown,

and time has thrown us free under the timeless moon.

The Snow Man

by

Wallace Stevens

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Come Lord and Lift

by T. Merrill

Come Lord, and lift the fallen bird

Abandoned on the ground;

The soul bereft and longing so

To have the lost be found.

The heart that cries—let it but hear

Its sweet love answering,

Or out of ether one faint note

Of living comfort wring.

The Death of a Toad

by Richard Wilbur

A toad the power mower caught,

Chewed and clipped of a leg, with a hobbling hop has got

To the garden verge, and sanctuaried him

Under the cineraria leaves, in the shade

Of the ashen and heartshaped leaves, in a dim,

Low, and a final glade.

The rare original heartsblood goes,

Spends in the earthen hide, in the folds and wizenings, flows

In the gutters of the banked and staring eyes. He lies

As still as if he would return to stone,

And soundlessly attending, dies

Toward some deep monotone,

Toward misted and ebullient seas

And cooling shores, toward lost Amphibia's emperies.

Day dwindles, drowning and at length is gone

In the wide and antique eyes, which still appear

To watch, across the castrate lawn,

The haggard daylight steer.

To Earthward

by Robert Frost

Love at the lips was touch

As sweet as I could bear;

And once that seemed too much;

I lived on air

That crossed me from sweet things,

The flow of – was it musk

From hidden grapevine springs

Downhill at dusk?

I had the swirl and ache

From sprays of honeysuckle

That when they’re gathered shake

Dew on the knuckle.

I craved strong sweets, but those

Seemed strong when I was young:

The petal of the rose

It was that stung.

Now no joy but lacks salt,

That is not dashed with pain

And weariness and fault;

I crave the stain

Of tears, the aftermark

Of almost too much love,

The sweet of bitter bark

And burning clove.

When stiff and sore and scarred

I take away my hand

From leaning on it hard

In grass or sand,

The hurt is not enough:

I long for weight and strength

To feel the earth as rough

To all my length.

Depths

by Richard Moore

Once more home is a strange place: by the ocean a

big house now, and the small houses are memories,

once live images, vacant

thoughts here, sinking and vanishing.

Rough sea now on the shore thundering brokenly

draws back stones with a roar out into quiet and

far depths, darkly to lie there

years, years—there not a sound from them.

New waves out of the night's mist and obscurity

lunge up high on the beach, spending their energy,

each wave angrily dying,

all shapes endlessly altering,

yet out there in the depths nothing is modified.

Earthquakes won't even move—no, nor the hurricane—

one stone there, nor a glance of

sun's light stir its identity.

Those Winter Sundays

by Robert Hayden

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he'd call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love's austere and lonely offices?

A Noiseless Patient Spider

by Walt Whitman

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark'd where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark'd how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch'd forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form'd, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

To Celia

by Ben Jonson

Drink to me, only, with thine eyes,

And I will pledge with mine;

Or leave a kiss but in the cup,

And I'll not look for wine.

The thirst that from the soul doth rise,

Doth ask a drink divine:

But might I of Jove's nectar sup,

I would not change for thine.

I sent thee, late, a rosy wreath,

Not so much honouring thee,

As giving it a hope, that there

It could not withered be.

But thou thereon didst only breathe,

And sent'st back to me:

Since when it grows, and smells, I swear,

Not of itself, but thee.

To Daffodils

by Robert Herrick

Fair daffodils, we weep to see

You haste away so soon.

As yet the early-rising sun

Hath not attained his noon.

Stay, stay,

Until the hasting day

Has run

But to the even-song;

And, having prayed together, we

Will go with you along.

We have short time to stay, as you;

We have as short a spring;

As quick a growth to meet decay,

As you, or any thing.

We die.

As your hours do, and dry

Away

Like to the summer's rain;

Or as the pearls of morning's dew

Ne'er to be found again.

Cradle Song

by William Blake

Sleep, sleep, beauty bright,

Dreaming in the joys of night;

Sleep, sleep; in thy sleep

Little sorrows sit and weep.

Sweet babe, in thy face

Soft desires I can trace,

Secret joys and secret smiles,

Little pretty infant wiles.

As thy softest limbs I feel

Smiles as of the morning steal

O'er thy cheek, and o'er thy breast

Where thy little heart doth rest.

O the cunning wiles that creep

In thy little heart asleep!

When thy little heart doth wake,

Then the dreadful night shall break.

Tears, Idle Tears

by Lord Alfred Tennyson

Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean,

Tears from the depth of some divine despair

Rise in the heart, and gather to the eyes,

In looking on the happy Autumn fields,

And thinking of the days that are no more.

Fresh as the first beam glittering on a sail,

That brings our friends up from the underworld,

Sad as the last which reddens over one

That sinks with all we love below the verge;

So sad, so fresh, the days that are no more.

Ah, sad and strange as in dark summer dawns

The earliest pipe of half-awakened birds

To dying ears, when unto dying eyes

The casement slowly grows a glimmering square;

So sad, so strange, the days that are no more.

Dear as remembered kisses after death,

And sweet as those by hopeless fancy feigned

On lips that are for others; deep as love,

Deep as first love, and wild with all regret;

O Death in Life, the days that are no more.

Acquainted With The Night

by Robert Frost

I have been one acquainted with the night.

I have walked out in rain—and back in rain.

I have outwalked the furthest city light.

I have looked down the saddest city lane.

I have passed by the watchman on his beat

And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain.

I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet

When far away an interrupted cry

Came over houses from another street,

But not to call me back or say good-by;

And further still at an unearthly height,

One luminary clock against the sky

Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right.

I have been one acquainted with the night.

The Windhover

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.

Song

by John Donne

Go and catch a falling star,

Get with child a mandrake root,

Tell me where all past years are,

Or who cleft the devils foot;

Teach me to hear mermaids singing,

Or to keep off envy's stinging,

And find

What wind

Serves to advance an honest mind.

If thou be'st born to strange sights,

Things invisible to see,

Ride ten thousand days and nights

Till Age snow white hairs on thee;

Thou, when thou return'st wilt tell me

All strange wonders that befell thee,

And swear

No where

Lives a woman true and fair.

If thou find'st one let me know;

Such a pilgrimage were sweet.

Yet do not; I would not go,

Though at next door we might meet.

Though she were true when you met her,

And last, till you write your letter,

Yet she

Will be

False, ere I come, to two or three.

The Convergence Of The Twain

by Thomas Hardy

Lines on the loss of the "Titanic"

In a solitude of the sea

Deep from human vanity,

And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she.

Steel chambers, late the pyres

Of her salamandrine fires,

Cold currents thrid, and turn to rhythmic tidal lyres.

Over the mirrors meant

To glass the opulent

The sea-worm crawls—grotesque, slimed, dumb, indifferent.

Jewels in joy designed

To ravish the sensuous mind

Lie lightless, all their sparkles bleared and black and blind.

Dim moon-eyed fishes near

Gaze at the gilded gear

And query: "What does this vaingloriousness down here?"...

Well: while was fashioning

This creature of cleaving wing,

The Immanent Will that stirs and urges everything

Prepared a sinister mate

For her—so gaily great—

A Shape of Ice, for the time far and dissociate.

And as the smart ship grew

In stature, grace, and hue,

In shadowy silent distance grew the Iceberg too.

Alien they seemed to be;

No mortal eye could see

The intimate welding of their later history,

Or sign that they were bent

By paths coincident

On being anon twin halves of one august event,

Till the Spinner of the Years

Said "Now!" And each one hears,

And consummation comes, and jars two hemispheres.

Luke Havergal

by Edward Arlington Robinson

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal,

There where the vines cling crimson on the wall,

And in the twilight wait for what will come.

The leaves will whisper there of her, and some,

Like flying words, will strike you as they fall;

But go, and if you listen, she will call.

Go to the western gate, Luke Havergal—

Luke Havergal.

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies

To rift the fiery night that's in your eyes;

But there, where western glooms are gathering

The dark will end the dark, if anything:

God slays Himself with every leaf that flies,

And hell is more than half of paradise.

No, there is not a dawn in eastern skies—

In eastern skies.

Out of a grave I come to tell you this,

Out of a grave I come to quench the kiss

That flames upon your forehead with a glow

That blinds you to the way that you must go.

Yes, there is yet one way to where she is,

Bitter, but one that faith may never miss.

Out of a grave I come to tell you this—

To tell you this.

There is the western gate, Luke Havergal,

There are the crimson leaves upon the wall,

Go, for the winds are tearing them away,—

Nor think to riddle the dead words they say,

Nor any more to feel them as they fall;

But go, and if you trust her she will call.

There is the western gate, Luke Havergal—

Luke Havergal.

Full Fathom Five

by William Shakespeare

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark! now I hear them — ding-dong, bell.

Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802

by

William Wordsworth

Earth has not anything to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne'er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

Song of Solomon

attributed to King Solomon

I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys.

As the lily among thorns, so is my love among the daughters.

As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons.

I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste.

He brought me to the banqueting house, and his banner over me was love.

Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples: for I am sick of love.

His left hand is under my head, and his right hand doth embrace me.

I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes,

and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor wake my love, till he please.

Ozymandias

by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

A Red, Red Rose

by Robert Burns

Oh my luve is like a red, red rose,

That's newly sprung in June:

Oh my luve is like the melodie,

That's sweetly play'd in tune.

As fair art thou, my bonie lass,

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a' the seas gang dry.

Till a' the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi' the sun;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

While the sands o' life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only luve!

And fare thee weel a while!

And I will come again, my luve,

Tho' it were ten thousand mile!

Upon Julia's Clothes

by Robert Herrick

Whenas in silks my Julia goes,

Then, then, methinks, how sweetly flows

The liquefaction of her clothes.

Next, when I cast mine eyes and see

That brave vibration each way free,

Oh, how that glittering taketh me!

Spring Song

by Lucy Maud Montgomery

Hark, I hear a robin calling!

List, the wind is from the south!

And the orchard-bloom is falling

Sweet as kisses on the mouth.

In the dreamy vale of beeches

Fair and faint is woven mist,

And the river's orient reaches

Are the palest amethyst.

Every limpid brook is singing

Of the lure of April days;

Every piney glen is ringing

With the maddest roundelays.

Come and let us seek together

Springtime lore of daffodils,

Giving to the golden weather

Greeting on the sun-warm hills.

To continue reading more of the most beautiful poems of all time,

please click here: Poems

by the Masters of English Poetry.

Other notable beautiful poems and songs of the English language include:

The Darkling Thrush

by Thomas Hardy

Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold

They Flee from Me that Sometime Did Me Seek by Sir Thomas Wyatt

Ode: Intimations of Immortality by William Wordsworth

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard by Thomas Gray

The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls by Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow

A Psalm of Life by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Highwayman

by Alfred Noyes

After the Persian by Louise Bogan

Voyages by Hart Crane

Forgetfulness by Hart Crane

A Last Word by Ernest Dowson

The Old Lutheran Bells at Home by Wallace Stevens

The Idea of Order at Key West by Wallace Stevens

Tea at the Palace of Hoon by Wallace Stevens

Vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat inchohare longam

by Ernest Dowson

Fern Hill by Dylan Thomas

And Death Shall Have No Dominion by Dylan Thomas

Sarabande On Attaining The Age Of Seventy-Seven

by Anthony Hecht

Exile by Hart Crane

Time in Eternity by T. Merrill

Friday

by Ann Drysdale

The Lovemaker

by Robert Mezey

The Ghost Ship by

A. E. Stallings

Part 6 from The Dark Side of the Deity: Interlude by

Joe M. Ruggier

After the Rain

by Jared Carter

Sea Fevers by Agnes Wathall

Diamonds and Rust by Joan Baez

I Walk the Line by Johnny Cash

A Change is Gonna Come by Sam Cooke

Blowin' in the Wind by Bob Dylan

Stan by Eminem

Man in the Mirror by Michael Jackson

Been to Canaan by Carole King

Imagine by John Lennon

Let It Be by Paul McCartney

Fallin' by Alicia Keys

I Will Always Love You by Dolly Parton

When Doves Cry by Prince

Tears of a Clown by Smokey Robinson

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen

Heart of Gold by Neil Young

Wild Horses by the Rolling Stones (Mick Jagger and

Keith Richards)

Eleanor Rigby by the Beatles (Paul McCartney and John

Lennon)

Bridge Over Troubled Water by Simon and Garfunkel

(Paul Simon)

Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen

Battle Hymn of the Republic by Julia Ward Howe

This Land Is Your Land by Woody Guthrie

Where Have All the Flowers Gone by Pete Seeger

in Just- by e. e. cummings

since feeling is first by e. e. cummings

Spring and Fall, to a Young Child

by Gerard Manley Hopkins

Dulce et Decorum Est by Wilfred Owen

The Armadillo by Elizabeth Bishop

Skunk Hour by Robert Lowell

Afton Water

by Robert Burns

The Light of Other Days

by Tom Moore

The Negro Speaks of Rivers

by Langston Hughes

A Blessing

by James Wright

Naming of Parts

by Henry Reed

To The Virgins, To Make Much Of Time by Robert Herrick

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T. S. Eliot

Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot

Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

She Walks in Beauty by Lord Byron

So We'll Go No More A-Roving by Lord Byron

This Is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams

Ode to Autumn by John Keats

Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats

Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats

Bright Star by John Keats

Howl by Allen Ginsburg

Daddy by Sylvia Plath

Sonnet 18: Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day? by William Shakespeare

Sonnet 73: That Time of Year Thou May'st in Me Behold by William Shakespeare

Sonnet 116: Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds by William Shakespeare

Funeral Blues by W. H. Auden

Kubla Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The World Is Too Much with Us by William Wordsworth

It Is a Beauteous Evening, Calm and Free

by William

Wordsworth

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud by William Wordsworth

Birches by Robert Frost

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening by Robert Frost

The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost

Mending Wall by Robert Frost

Directive by Robert Frost

After Apple Picking by Robert Frost

The Most of It by Robert Frost

The Lake Isle of Innisfree by William Butler Yeats

Sailing to Byzantium by William Butler Yeats

The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats

When You Are Old by William Butler Yeats

An Irish Airman Foresees His Death by William Butler Yeats

Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare

I Am by John Clare

Poem in October by Dylan Thomas

Bagpipe Music by Louis MacNeice

Wulf and Eadwacer by Anonymous

Tom O' Bedlam's Song by Anonymous

The Lie by Sir Walter Raleigh

One Day I Wrote Her Name upon the Strand by Sir Edmund Spenser

Prothalamion by Sir Edmund Spenser

With How Sad Steps, O Moon, Thou Climb'st the Skies by Sir Philip Sidney

The Passionate Shepherd to His Love by Christopher Marlowe

On My First Son by Ben Jonson

Virtue by George Herbert

Paradise Lost by John Milton

Lycidas by John Milton

When I Consider How My Light Is Spent by John Milton

To His Coy Mistress by Andrew Marvell

They Are All Gone into the World of Light by Henry Vaughan

The Tyger by William Blake

The Lamb by William Blake

London by William Blake

The Sick Rose by William Blake

A Poison Tree by William Blake

Proud Masie by Sir Walter Scott

Rose Aylmer by Walter Savage Landor

Jenny Kissed Me by Leigh Hunt

Ode to the West Wind by Percy Bysshe Shelley

To a Skylark by Percy Bysshe Shelley

I Am by John Clare

The Bells by Edgar Allan Poe

Annabelle Lee by Edgar Allen Poe

To Helen by Edgar Allan Poe

The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe

A Dream Within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe

The Eagle by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

The Splendor Falls by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Mariana by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Ulysses by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

My Last Duchess by Robert Browning

Meeting at Night by Robert Browning

Parting at Morning by Robert Browning

Howl by Allen Ginsberg

When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer by Walt Whitman

When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd by Walt

Whitman

Omeros by Derek Walcott

Love After Love by Derek Walcott

The New Colossus by Emma Lazarus

To a Waterfowl by William Cullen Bryant

Thanatopsis by William Cullen Bryant

Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll

Don Juan by Lord Byron

The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope

Mac Flecknoe by John Dryden

Paul Revere's Ride by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

The Charge of the Light Brigade by Alfred, Lord

Tennyson

If by Rudyard Kipling

Invictus by William Ernest Henley

It is Here by Harold Pinter

If You Forget Me by Pablo Neruda (translation)

Archaic Torso of Apollo by Rainer Maria Rilke

(translation)

Autumn Day by Rainer Maria Rilke (translation)

The Panther by Rainer Maria Rilke (translation)

The Inferno by Dante (translation)

The Divine Comedy by Dante (translation)

The Odyssey by Homer (translation)

The Iliad by Homer (translation)

The Aeneid by Virgil (translation)

The Sonnets of Petrarch (translation)

Related pages:

Perfect Poems,

The Best Sonnets,

The Best Villanelles,

The Best Ballads,

The Best Sestinas,

The Best Rondels and Roundels,

The Best Kyrielles,

The Best Couplets,

The Best Quatrains,

The Best Haiku,

The Best Limericks,

The Best Nonsense Verse,

The Best Poems for Kids,

The Best Light Verse,

The Best Poem of All Time,

The Best Poems Ever Written,

The Best Poets,

The Best of the Masters,

The Most Popular Poems of All Time,

The Best American Poetry,

The Best Poetry Translations,

The Best Ancient Greek Epigrams and Epitaphs,

The Best Anglo-Saxon Riddles and Kennings,

The Best Old English Poetry,

The Best Lyric Poetry,

The Best Free Verse,

The Best Story Poems,

The Best Narrative Poems,

The Best Epic Poems,

The Best Epigrams,

The Most Beautiful Poems in the English Language,

The Most Beautiful Lines in the English Language,

The Most Beautiful Sonnets in the English Language,

The Best Elegies, Dirges & Laments,

The Best Poems about Death and Loss,

The Best Holocaust Poetry,

The Best Hiroshima Poetry,

The Best Anti-War Poetry,

The Best Religious Poetry,

The Best Spiritual Poetry,

The Best Heretical Poetry,

The Best Thanksgiving Poems,

The Best Autumnal Poems,

The Best Fall/Autumn Poetry,

The Best Dark Poetry,

The Best Halloween Poetry,

The Best Supernatural Poetry,

The Best Dark Christmas Poems,

The Best Vampire Poetry,

The Best Love Poems,

The Best Urdu Love Poetry,

The Best Erotic Poems,

The Best Romantic Poetry,

The Best Love Songs,

The Ten Greatest Poems Ever Written,

The Greatest Movies of All Time,

England's Greatest Artists,

Visions of Beauty,

What is Poetry?,

The Best Abstract Poetry,

The Best Antinatalist Poems and Prose,

Early Poems: The Best Juvenilia,

Human Perfection: Is It Possible?,

The Best Book Titles of All Time,

Sentimental Poetry: Is it Wrong to Like It?,

The Best Sentimental Poems,

What is

Poetry?, The Best Books of All

Time, The

Best Writing in the English Language

The HyperTexts